by Stanley Pranin, November 30, 2006

A visit to the bookstore

The other day I visited a large bookstore in Las Vegas. It so happened that I had a couple of hours to look around at my leisure while waiting for my son to finish a music lesson. This was the first time in years I remember having had this luxury. As I scanned the bookshelves going randomly from subject to subject, I decided to check out the offerings of books and magazines on martial arts, especially aikido. What I found surprised me, to say the least!

Let me backup a bit. I remember about ten years ago while we still published the print version of Aikido Journal having visited bookstores in Southern California on a regular basis to monitor the handling and stocking of the magazine and to keep abreast of happenings in the world of martial arts publications. At that time, there was considerable activity in the field: several martial arts magazines could be found on the shelves; nearly an entire bookcase was devoted to martial arts titles, and fascinatingly, there were more books on aikido than any other martial art subject.

This time, however, I was in for a shock. There was but one copy of Black Belt Magazine and no other martial arts magazines whatsoever. The situation for martial arts books was equally bleak. They occupied only one shelf of a bookcase and, of this slim selection, only five or six titles dealt with aikido. If the lack of availability of martial arts publications in this bookstore is representative of current circumstances in the publishing world, it would seem that aikido, and the martial arts in general, are losing the battle to capture the attention of a public overwhelmed with literally thousands of options when it comes to pastime activities.

This experience at the bookstore caused me to reflect on conversations I have had over the last few years with aikido collegues who operate their own schools. I have heard many stories that lend credence to the belief that the martial arts are in a decline. Teachers have spoken of falls in student enrollment, lost leases, dojo closures, and difficulties in making ends meet. In several cases, the instructors I have spoken with operate large schools that have experienced success in the past but have recently fallen on hard times. If these impressions are indicative of reality insofar as concerns the martial arts, I find myself asking what has happened in the field in the last decade or so that has brought us to this lamentable state of affairs.

Martial Arts: Lost in a sea of choices

As I alluded to above, people faced with leisure time looking for a form of exercise or personal improvement have a plethora of options awaiting them. For those inclined to engage in some form of exercise, there are the traditional western sports and scores of newly developed recreational activities that did not even exist 20 years ago. Those who don’t wish to undertake a physical activity but prefer a more sedentary lifestyle have sports on tv to watch 24 hours a day in addition to the usual television fare. Of course, they can also read a book, but fewer and fewer do. But what has really changed the pastime landscape in the last few years is, of course, the advent of the Internet.

Never before has there been such an explosion of new technologies that bring information on practically every conceivable topic to one’s fingertips ready for instant access. Today, the ability of a person to entertain a question in their mind, then seek out answers to that question or solve a related problem is nothing short of revolutionary. Morever, this is not technology reserved for the rich or a societal elite. It is available to people of all social strata, and even large segments of society in developing countries have or will soon have access to interconnected computers.

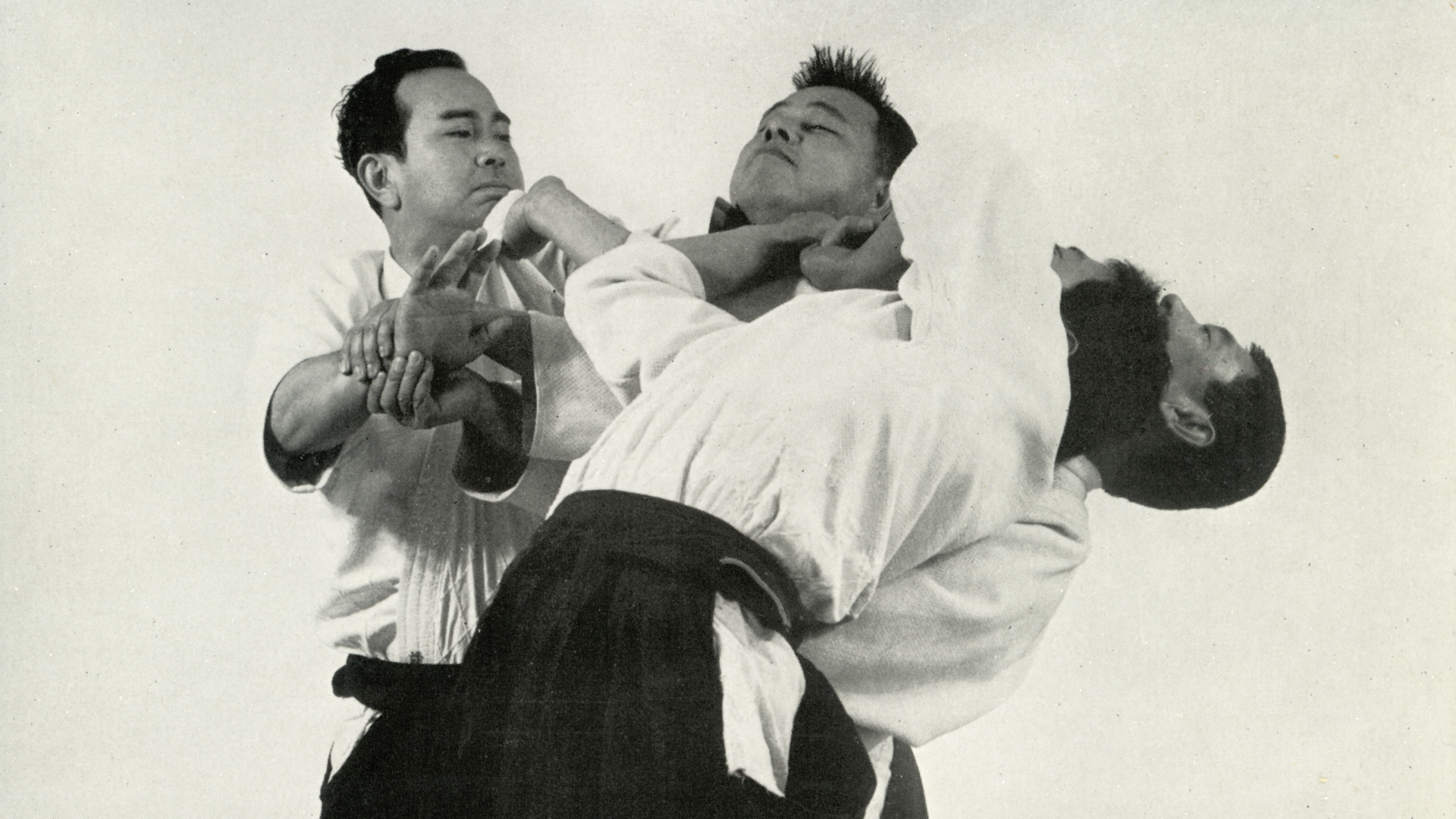

This wide array of options for spending one’s time means that a potential activity must stand out in some way to grab the attention of the public in order to become a viable choice. I think it is in this respect that martial arts in general and, aikido specifically, are lacking. The newness and exotic image of the martial arts in the west has worn off since public awareness of them began more than 40 years ago. We are no longer in the 1960s when Kurosawa-directed samurai flics featuring the likes of Toshiro Mifune enjoyed a cult following. Long gone are the days when Bruce Lee and the Karate Kid captured the public’s fancy. The last hurrah may have been Steven Seagal’s films which, though presenting a gritty, distorted image of aikido, were at least a strong attention grabber that for a time enjoyed wide success. The public now prefers the comedic and martial skills of Jackie Chan and the fantasy martial performances of stars like Jet Li served up by Chinese filmmakers.

It must be kept in mind, too, that we are dealing with a generation of people who have a very short attention span, no doubt due partly to a steady diet of tv commercials, action movies, video games, and the like, that flash thousands of images on the screen in rapid succession. If by some small miracle, a person joins a martial art school, the odds are against them continuing for any length of time.

Failure to keep alive roots and core principles of the arts

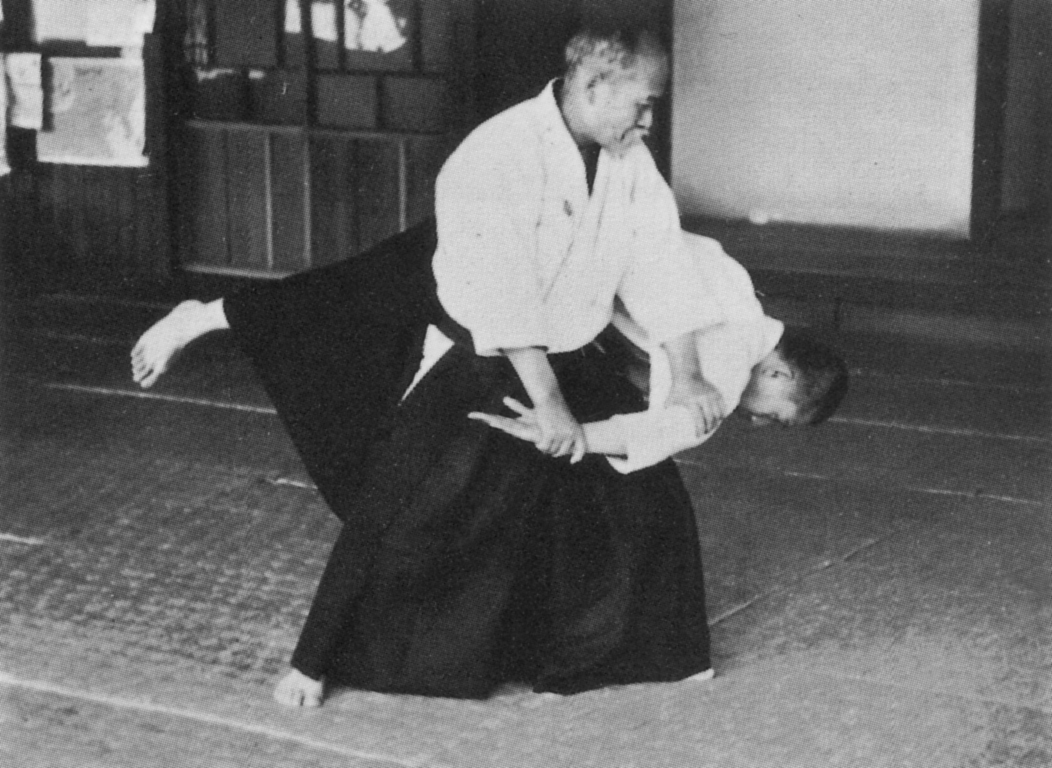

Although I believe this is also true of the martial arts in general, aikido may have lost ground in recent years because of its failure to clearly articulate the principles underlying the art. Aikido instructors may give lip service to the ideas of founder Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969), but even experienced teachers lack an understanding of the art’s cultural and historical background and are ignorant of the arduous process that led to its creation.

Similarly, in an effort to make the Shinto-based beliefs of Ueshiba palatable to an international audience, most of the religious language and imagery that characterized his speech and writings have been excised. What remains is a simplified form of expression that, although philosophical enough, has lost its unique Japanese cultural context.

Since there is but a tenuous appreciation of the roots of the art in the community, aikido has little to distinguish itself in the eyes of an unsophisticated public from the old-style jujutsu forms that survive and have been propogated in the west, usually in modified form.

I think this is very much the case with most martial arts. It is common for them to distance themselves from the techniques and principles of the founding figure over the course of time. Obviously, if this process continues long enough, the art becomes so far removed from the original forms that it becomes a stretch to call it by the same name. Practitioners of the martial arts ignore their history at their peril.

Aikido and martial arts: the double-edged sword of competitive sports

Another key to understanding the public’s failure to grasp aikido’s basic principles is the fact that the art is non-competitive. In the minds of many, martial arts are merely a class of sports. The average person cannot discern the differences in practice and purpose between traditional martial disciplines that evolved for self-defense and personal development and modern sports.

As an example, take the case of judo. Jigoro Kano (1860-1938) succeeded in synthesizing elements of the two major jujutsu systems that survived in Japan to the end of the 19th century. He achieved success by devising a competitive form that, having achieved a certain popularity, was eventually adopted into Japan’s educational system. The conversion of jujutsu into a sport and its acceptance by the educational establishment assured judo’s dissemination throughout Japan and later far beyond its shores. Kano also embraced the Olympic ideal espoused by Frenchman Pierre Coubertin and worked hard to get sport judo accepted into the Olympics. Sadly, the judo founder did not live to see his dream fulfilled, but judo did finally become an Olympic sport starting with the Tokyo games in 1964.

Something that Kano didn’t bargain for was the negative effect that competition would have on sport judo. Competitors began adopting strange strategies to achieve victory that, while still within the bounds of the rules, made absolutely no sense from the standpoint of fighting or defense, the original rationale of the art. For example, at one early stage in judo’s history, some competitors skilled in “newaza” or grappling techniques would immediately fall down in an effort to force their opponents to the mat where they would have an advantage.

Kano himself became critical of competitive judo in his later years and regretted some of his early decisions having seen how the sport mentality and culture adversely affected his creation. Though judo has continued to be practiced widely thanks in large part to it being institutionalized in Japan, few regard it as a self-defense system per se since larger athletes even of a lesser skill level will usually defeat smaller counterparts. As Minoru Mochizuki often said, for many, “ju-do” (???the gentle path) has become “ju-do” (???the heavy path)!

Various aikido styles have experimented with forms of competition with mixed success. The most prominent example is Tomiki Aikido, created by Kenji Tomiki (1900-1979) who was heavily influenced by both Jigoro Kano and Morihei Ueshiba. Starting in the late 1950s at Waseda University in Tokyo, Tomiki patterned his form of competiton on the model of Kano’s judo. He was only partially successful and was shunned by most of the other styles of aikido for having introduced the notion of competition into aikido in clear opposition to Ueshiba’s original principles. Tomiki’s successors continue to experiment with his theories by modifying the rules of sport aikido in an effort to realize Tomiki’s ideal.

Somewhat ironically, both Yoshikan Aikido and Shinshin Toitsu Aikido, founded by Gozo Shioda and Koichi Tohei respectively, introduced a sporting aspect, albeit minor, into their styles in the 1990s. Demonstrators compete against one another based on a point system with the victors receiving trophies and other awards.

Even the Aikikai World Headquarters, while steadfastly maintaining that aikido is a non-competitive martial art, joined the International World Games Association some years ago in order to gain further recognition for the art on a world stage. Aikido is designated a “demonstration sport” within the context of this organization but, because it lacks a competitive form, it is not recognized as a full member. Recently, the IWGA has pressured the Aikikai to develop a form of competition if it is to remain in the Association. The Aikikai has responded negatively and its future participation in the IWGA remains in doubt.

Thus, the conversion of martial arts into sports cuts two ways: it can be a means to achieve the popularization and survival of an art; however, it also carries with it the risk of transforming the discipline into something that runs contrary to the art’s core principles, judo and kendo being good examples. Mixed martial arts, UFC, K1, Vale Tudo, and other knockdown-dragout fighting exhibitions are the rage today and are other examples of how elements of several traditional martial arts can be stitched together, converted into sports, and end up practically unrecognizable from the original martial forms.

Lack of business acumen

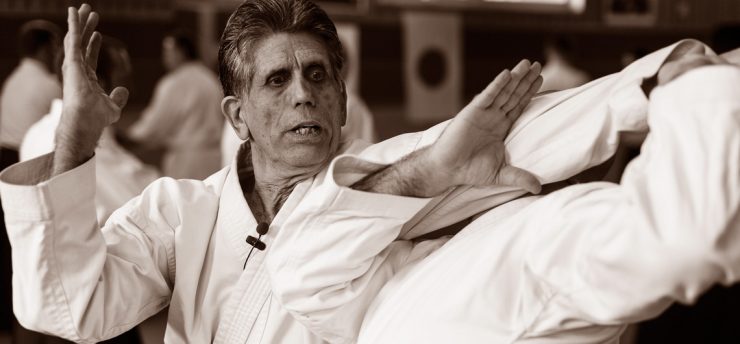

Another key to an explanation of why it seems that martial arts are in a period of decline has to do with the business skills—or lack thereof—of many instructors who choose to embark on careers as professionals. Technical and pedagocial skills alone are not enough to assure the success of instructors opening up martial arts schools. An understanding of management and accounting skills, communication abilities, local laws, community service opportunities, and many other areas needed for success in running a business is required.

One additional contributing factor, and I think it is a sign of our times, is that most business operators begin with a weak financial base. That is, they have little or no savings, and opt to take out loans in order to finance their martial arts schools. Since they have no reserves, financially or psychologically, they begin their business career with two strikes against them. Some go under at the first sign of financial hardship. Others last for a while, but never can seem to get ahead and eventually abandon their businesses. Been there, done that!

In this short piece, I have attempted merely to touch upon some of the problems I see afflicting martial arts in today’s competitive and unforgiving world. Aikido and its martial bretheren indeed have their work cut out for them if they plan to survive this relentless march forward in this technologically advanced age. It will take well-rounded, skilled leaders and professionals who can effectively articulate the unique aspects of the arts they represent to turn the tide faced with an audience bombarded by choices.

I think we would do well as an aikido enthusiasts to continue engaging in frequent discussions that cut across organizational lines, to offer one another advice and encouragement, and pool our resources to get across our message. Certainly, this same Internet that is still in its infancy and that has almost single-handedly been responsible for the information glut we see today can also be used as a tool for the rejuvenation of aikido and other martial arts. If practitioners band together to form true democratic communities that transcend national boundaries, there is every opportunity to inject new spirit into the arts and bring them back into a position of prominence in the public’s consciousness.

Stanley Pranin, November 30, 2006, Las Vegas, Nevada

Very informative article. before i hardly knew about aikido and its principles.

Being an aikidoka in the Tomiki aikido system for 32 years and also having previous experience in judo as a child into my teens, then amatuer boxing during my military service, followed by trying out Wing chun Gung fu and Goju ryu Karate Do for a year concurrently, I found the Tomiki system of aikido had all those elements in its randori shiai competition, combined with kata, was a well rounded system… Its obvious to me that some kind of testing platform to test one’s mettle in any martial art in the use of the techniques, learnt in both kata and randori or sport shiai is needed… I’m now retired from aikido, but have seen the reason and rationale of why Tomiki stuck to his “guns”… To me a martial art is about the use of techniques to defend oneself, if they’re unlucky enough to find oneself in a scenario where its required, as well as a form of physical education, which can be found in most physical sports… This to me is the reason why anyone would want to practice a martial art … Once that has been lost, then its bound to happen… One would be far better off from a health point of view to do such things as yoga or even gymnastics, dance or whatever floats the boat physically, but to try and turn a martial art into something that can only be described as martial dance, is most probably the reason for its decline… Had I wanted a physical education for health, and I had my time over again, I would’ve done dance or gymnastics!! Far better for health than aikido!!

I think it was just swings, like any other sport has them