“Ueshiba Sensei’s aikido embodied the essence of Japanese culture

and I saw it as something that could be very important to Japan in the future.”

From Aikido Journal #101 (1994)

AJ: Sensei, I understand that you began aikido after entering Waseda University?

Tada Sensei: Yes, but because of the war I was unable to enroll in the dojo until March of 1950.

I also believe you began karate when you entered the university, and later felt drawn to aikido…

Actually, I didn’t do that much karate, although I do hold a dan ranking. At first I was practicing both arts, but I began spending more time practicing aikido, and it became impossible to do both. It wasn’t that I thought one was better than the other, but rather that I admired Morihei Ueshiba Sensei greatly. I had known him through my father since I was a boy.

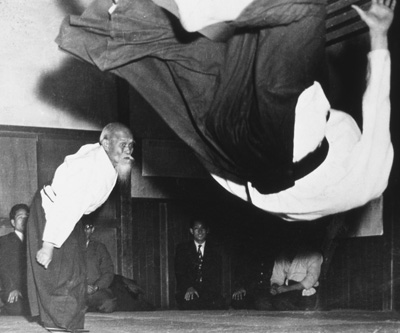

In 1942, I was in Shinkyo (present-day Chang Chun, Manchuria), but I just missed Ueshiba Sensei’s performance at the famous Kenkoku University Tenth Anniversary Martial Arts Demonstration. My cousin, who is one year older than me, told me it was a fantastic demonstration. Apparently hardly anyone could take Ueshiba Sensei’s ukemi. They weren’t just being thrown, it was if they were being shocked by high-voltage electricity.

In issue number four of Aikido Tankyu [a periodical published by the Aikikai Hombu Dojo], you wrote that you were very surprised and impressed by Ueshiba Sensei’s unusual way of thinking.

When I enrolled in the dojo I was twenty years old, and Sensei was sixty-seven or so, a difference of about forty-seven years. But he threw me so easily no matter how strongly I attacked, that there seemed, in that respect, to be no difference in our ages at all. Looking back on it now it seems perfectly understandable, of course.

In any case, he had a unique air about him and he was filled with an unusual energy. I felt I had met a true martial arts expert.

Did you enter the Tempukai at the same time you began aikido?

When I entered the Hombu Dojo most of the people training there were members of either the Tempukai or the Nishikai. Of course, at the time there were only six or seven people at the dojo. Among them were Keizo Yokoyama and his younger brother, Yusaku, both of whom were students at Hitotsubashi University. Yusaku spent the last years of the war in the naval academy and entered the university after the war ended. It was he who introduced me to the Tempukai and the Ichikukai. After that another person taught me about fasting exercises. These practices, along with the teachings of Morihei Ueshiba Sensei, became the basis of my training.

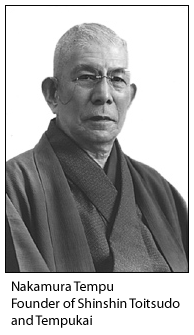

I was introduced to the Tempukai in June of the same year that I entered the Aikikai. Tempu Nakamura Sensei was then conducting monthly study sessions at the Gekkoden of Gokokuji Temple. Like the Aikikai, the Tempukai did little to promote itself publicly, and people became members of the Tempukai through the introduction of other members. I met Tempu Sensei and after I heard what he had to say, I joined immediately.

Were Ueshiba Sensei and Tempu Sensei acquainted with one another?

Yes. It was before I enrolled in the dojo, but it seems they had met once through an introduction by Tadashi Abe’s father, who was both a member of the Tempukai and a student of Ueshiba Sensei. Originally, the Tempukai was known as the Toitsu Tetsuigakkai (Society for the Study of Unification of Medicine and Philosophy), and it focused on the unification of mind and body. I participated in many of Tempu Sensei’s experiments, so I came to know a lot about him.

How long were you active in the Tempukai?

Until I went to Europe in October 1964. Tempu Sensei passed away in December 1968. During my six years in Europe, Morihei Ueshiba Sensei and Tempu Sensei, as well as my grandfather, all passed away.

I’ve heard that Tempu Sensei was an expert with the sword.

Yes, he was an expert in Zuihen-ryu battojutsu. He took his name, Tempu, from the Chinese characters “ten” and “pu” used to write the name of the Zuihen-ryu’s amatsukaze form, at which he was particularly skilled. Tempu Sensei was a descendant of Lord Tachibana, the daimyo in Yanagawa. The martial arts were so popular in Yanagawa that it ranked with the Saga clan of Kyushu, which was famed for the book titled Hagakure [a classic text on bushido, dictated by Tsunetomo Yamamoto in 1716]. The content of Tempu Sensei’s speeches was quite distinctive in that most of what he said originated more from his actual experience than from any intellectual process. Ueshiba Sensei was the same way. Ideas generated on an intellectual level don’t have nearly the same power to draw people.

Could you please tell us about the Ichikukai?

A man named Tetsuju Ogura was one of Tesshu Yamaoka’s last uchideshi. During the Taisho period, students and followers of Ogura together with members of the boat racing club of Tokyo Imperial University (present-day Tokyo University) created a society that practiced misogi (austerities, ritual purification). It was under the direction of Masatetsu Inoue. In the beginning, the Ichikukai gathered on the 19th of every month, in commemoration of Tesshu Yamaoka’s death on July 19th, so that’s why it was called the Ichikukai [ichiku in Japanese can mean “1 and 9,” i.e., 19].

When I joined, the meetings were held at an old Taisho period dojo in Nogata-machi in Nakano. From Thursday to Sunday we sat in seiza for about ten hours a day, chanting a passage from a norito (Shinto prayer), putting as much of our entire being into it as possible. It was something akin to chanting a mantra. After passing through this initiation you became a member, and then you could attend meetings once a month on Sunday. There they did a chanting exercise called ichiman-barai, which consisted of ringing a hand-bell ten thousand times. The sound of the bell doesn’t become clear and sharp until the movement of the hand becomes automatic. Many of my top students in the aikido classes I teach now do this practice.

Did you train with the ken or jo?

There was a period when O-Sensei would get angry when students in the dojo tried to train with the ken or jo, and he forbade them to do it. Later, though, he began teaching such things.

As a child I had practiced a tradition of Japanese archery that has been passed down in my family. I also used to practice kendo in junior high school. This was during the war so it was not at all sport-oriented. After I began training in aikido I would practice swinging the ken against a tree near my home.

Personal training is important no matter what art you practice. You should create your own training program, starting with running. In my twenties and into my thirties I used to get up at 5:30 every morning and run about fifteen kilometers. When I finished that I went home and practiced striking a bundle of sticks with a bokken (wooden sword). In those days the houses in Jiyugaoka were much further apart, so I could make as much noise as I pleased. I trained using the method of Jigen-ryu, which I had learned from O-Sensei at Iwama. It’s said that in the old days the warriors of the Satsuma domain [in Kyushu] would strike a bundle of brushwood ten thousand times every day, but I could only manage about five hundred at best. At first it made my hands go numb, but after a while I was able to strike a large tree with no problem. I’ve had my students at Waseda University and Gakushuin University train in this way. I find it to be one of the best training methods for aikido.

Of course, it’s not good to use excessive physical power. Just hold the bokken-or even an ordinary stick made of green wood-lightly and squeeze with the little finger and ring finger at the moment of impact. Speed and the ability to squeeze the fingers closed properly will develop naturally. This type of gentle practice is important, because if you practice using a lot of power all the time, you may end up throwing and applying joint techniques too strongly, and this can be dangerous.

It’s unfortunate that the limited space in our modern dojos doesn’t allow for much of this sort of training anymore. I’d like to gradually reorganize things to make such training more accessible.

What I have just described is a basic way to practice striking, but footwork, hand movement, and the development of ki through kokyuho are other important elements of one’s personal training.

You studied Morihei Sensei and devised your training method based on what you observed?

Yes. It is very important to observe your teacher’s personal training method very closely and learn it well; otherwise you may draw hasty and wrong conclusions and end up doing meaningless or mistaken training. In any case, you need to review what your teacher has taught you and attempt to discern something that represents the basic lines of it; then practice that over and over until you can do it. In this way you create your personal training method.

I think if you want to become an expert at what you do—whether it’s martial arts, sports, some kind of art, or whatever—then you need to train at least two thousand hours a year while in your twenties and thirties. That’s five to six hours a day. It probably depends on the person, but most of that time will be spent in personal training. After training on your own you can come to the dojo to confirm, try out, and work through whatever you’ve gained.

Using a tree as your aikido training partner is a very good way to practice training with power because you can strike much more forcefully than you could if your partner was another human being. It’s not appropriate to train recklessly hard when your partner is a person; you should spend that time working to develop correct, clean, razor-sharp lines.

Did Ueshiba Sensei ever talk to you about Daito-ryu or Onisaburo Deguchi?

Ueshiba Sensei always spoke very respectfully of his own teachers, including Sokaku Takeda Sensei and the Reverend Onisaburo Deguchi. The thing I remember most clearly from his talks about Daito-ryu is that he said he thought that it had a very excellent training method. After practice O-Sensei would often come back into the dojo and talk to us about various things.

I believe Ueshiba Sensei talked about religion, specifically about the Omoto religion…

Yes, and sometimes I understood quite clearly what he was talking about, while at other times it completely baffled me. But he also said to us, “This is just my way of speaking; I want each of you to understand what I am saying on your own terms, explore it deeply, and transmit it in words appropriate to the times.

Aikido is more beneficial to humanity than is generally realized, even when viewed from the perspective of someone like myself who specializes in aikido. In 1952, when I graduated from the university all of my friends were rather surprised at my decision to specialize in aikido, probably because it was so soon after the war. For me, however, Ueshiba Sensei’s aikido embodied the essence of Japanese culture and I saw it as something that could be very important to Japan in the future.

In actuality, however, aikido seems to have found its footing in Europe more quickly than in Japan. Still, when beginning with a blank slate like that, in a completely different cultural context, aikido training is impossible without a clear understanding of what aikido is and what the goals of training are. Without these it’s like jumping onto a train without knowing in what direction or to what destination it is headed. In other words, it is important to have a clear direction to aikido training from the very beginning. As far as deciding on training methods, it is unrealistic to ask people who want to train two or three times a week to train in the same way as people who want to train for several hours every day. It’s enough to have people train in a way that is meaningful for them within the context of their individual lifestyles. Those who want to become experts or who really want to explore aikido deeply, however, need to be very clear in their minds about where they’re going and how they’re going to get there.

I can’t say anything about what is wrong or right as far as training methods go. Most martial artists are not in a position to criticize the techniques of others, for there are too many cases in which someone who appears somewhat weak turns out to be extraordinarily strong.

Would you describe your organization in Italy?

The official name of the Italian Aikikai is L’Associazione di Cultura Tradizionale Giapponese (Traditional Japanese Culture Association) and it is recognized as an official organization by the Italian Ministry of Culture. As the name implies, aikido is practiced there as a form of traditional culture. It is very clear that what they are doing is different from any kind of sport. I think it may be difficult for Japanese living in Japan to understand this situation. To put it another way, they practice aikido as a method of “moving meditation.” In places like Italy, Switzerland, and Germany, the phrase “ki no renma” (cultivation of ki) is being used as is, in the original Japanese.

Of course, not everyone in those dojos practices keeping that sort of approach in mind. Some are more interested in becoming stronger to handle themselves better in a physical confrontation; others are motivated by a desire for better health; still others may simply want the enjoyment of trying something from a different culture. Young aikidoists intending to become instructors need to have clear and coherent goals for aikido training that includes all of these.

Modern Japanese martial arts are a rather special case. While they are referred to as budo, in reality they have been incorporated into the educational system since the Meiji period, and while they supposedly represent the spirit of traditional Japan, there are many cases in which certain spiritual aspects have been omitted.

The Meiji restoration, well over a hundred years ago, is said to have been a time of flowering of Western-style civilization in Japan; but it was precisely then that the study of Eastern ways became popular in Europe and the United States, along with the use of the subconscious and attention to the inner realms of the mind. These developed over a long period of time and after the war became well-known in the form of psychiatric medicine and therapeutic research. By contrast, Japan adopted a policy of “out with the Asian, in with the European,” an extremely problematic trend that continues even today and probably explains why there are surprisingly few Japanese who understand the essence of aikido.

Still, when I practice abroad, I actually do feel that there are some aspects of training that only Japanese will understand; not the training methods themselves, but rather things of a more general nature. Japanese ways of speaking, for instance, or the rhythm of Japanese lifestyle are things only a person who lives in Japan can understand. Kabuki and Noh dance are other examples. I feel I can understand them because I have lived in Japan.

I think that aikido training in Europe will evolve into a form appropriate for Europe. If language and ways of thinking and imagining are different, then ways of standing and moving will also be different.

If you think of the color red, then your body will do a movement that is “red.” The mind has that much influence on the body. These are very subtle aspects, however, that can only be discerned by close examination.

Sensei, you seem to have absorbed and incorporated an aikido way of thinking and moving into your body and your daily lifestyle, both inside and outside of the dojo. Could you tell us something of your everyday routine, perhaps beginning with your diet?

I was a complete vegetarian when I was in university. I also used to practice fasting and other austerities. That sort of thing is somewhat difficult for me now, so I concentrate on a diet of whole wheat bread, buckwheat noodles, and vegetables supplemented by seaweed, fish and seafood, and whole small fish.

I don’t drink alcohol except on special occasions such as at festivals and student gatherings. I don’t smoke, either. You can’t do kokyuho very well if you smoke, and you also lose control of the more subtle aspects of the five senses. You become unable to feel really microscopic differences. If you cannot feel these differences, you will be unable to sense the more subtle aspects of daily life. This is something that is difficult to understand within the routines of one’s normal lifestyle, but it becomes clearer at times when the senses are extra sharp, for example, when recovering from a three-week fast. Drinking alcohol everyday makes it especially difficult to achieve a real sense of clarity, no matter how hard you think about it or practice.

There are also many ways of eating. It can be said that we absorb the ki of the universe through our food. Therefore we should consider taking food and water as being just as important as breathing in the ki of the universe. I think perhaps the most important thing is to eat with the same feeling that O-Sensei always did, bringing the hands together in thanks before and after meals.

You spoke of Tesshu Yamaoka Sensei. He was very extreme in some aspects of his lifestyle…

There are many anecdotes about Tesshu Yamaoka. Some extreme reports tell of him sometimes eating tens of manju (rice flour dumplings filled with sweet bean paste) and hard-boiled eggs. There are many such stories about old heroes. I guess they didn’t worry about minor things like what they ate.

Until the Meiji period, Japanese people mastered kokyuho and developed their ki through discipline that began at a young age. In that respect, Japanese people today are completely different from Japanese back then. I’m referring to the sort of discipline that begins at birth, namely in the way children are taught and the nature of family life. The same is true of European lifestyle, where children are taken to church despite their lack of capacity to understand the experience. Thus, education begins from a young age there, too. Such experiences probably form the real core of a person. In pre-war Japan, the loyalty and patriotism stemming from bushido was equivalent, in a way, to European religious education. That has disappeared and unfortunately there is nothing to replace it. I think that aikido may be strong enough to fulfill that role.

Sensei, you have written that it is important to be able to practice in a scientific way…

Well, since the human body is, in one sense, a physical object, the way we move our bodies should be rational and scientific. Budo always includes training in things like how to sit and stand, as well as how to carry the body and how to be watchful. Especially emphasized are things like how to move the body, or how to shift the weight, or how to quickly gain the stability necessary to do techniques. Certainly there are principles that govern such things, and these should be understood thoroughly and applied to training.

The teacher’s role is to transmit these principles to students, but it is difficult to do this through logical explanations; the best way is for students to learn gradually through their bodies, without even realizing it. That’s why O-Sensei never explained his techniques. Explanations in words stop at the ears. Thus, simply following along as best you can is the fastest way to improve. It’s no good to think you can’t do something you’ve never experienced before just because you haven’t “learned” it. “Scientific” means to follow a set of principles, doesn’t it? It also implies the application of these principles. Therefore, even if there is something that you haven’t experienced before at all, you shouldn’t make the excuse that you can’t do something because you haven’t learned it.

Since methods of attack in the dojo are predetermined, the body may not be able to respond if suddenly attacked in a different way.

O-Sensei taught, for example, that shomenuchi represents attacks in which your partner’s power comes straight from the front, whether it’s a spear, a sword, a knife, or a kick. It’s not just an attack with the tegatana. You have to keep all of these possibilities well in mind during training. That means paying attention to how your body responds to each of these things, and to how you create lines and adapt your body. Moreover, you must have a special kind of energy to create an environment where people can really train and “be motivated to train.” Motivating everyone in the dojo requires kokyu power.

I’ve heard that before the war and during the Iwama period, when performing suwariwaza ikkyo, which is one of the most fundamental aikido techniques, Ueshiba Sensei would not give the opponent a chance to attack, but rather initiated the movement by sending forth his own ki…

That was known as the “cultivation of magnetism.” It involves a keen sense of kokyu that draws the opponent out like a piece of steel being instantly attracted by a magnet. There are three situations: You move first; you and your partner move simultaneously; your partner moves first. The technique is the same for all of these, really, and what is important in the end is the sort of state you maintain inside. If you look only at the outside form-for example, if you view techniques only as a means of self-defense-then you won’t be able to understand their overall meaning. They have to do with ki, not just the simple interaction of two physical bodies. Training is like a mirror reflecting your sensitivity to ki. The clearness of the mirror is the most important issue.

Could you talk about the difference between omote and ura?

Physically speaking, you do an ura technique when your partner has firmly planted his rear foot. When his rear foot is in motion, or is unsupported, then you do an omote technique. When your kokyu is passing freely through your partner you do omote. That’s how a technique becomes omote or ura. Such variation came out quite often in O-Sensei’s teachings. The point, however, is to be able to do techniques in any direction within a full 360 degrees. Omote and ura are not set forms or molds; they merely represent the idea that techniques may vary freely.

Sensei, you have in your mind a well-ordered curriculum of techniques you learned directly from O-Sensei…

Yes, I’ve taken a lot of care to keep them organized, and they form the basis of my own training program. I try to preserve not only techniques, but also the feeling of the overall conditions and atmosphere when I learned them. For example, I try to preserve an image of going to the dojo to train with O-Sensei. I leave my house in Jiyugaoka, go down the hill and catch the Toyoko line to Shibuya, transfer there to the Yamate Loop line to Shinjuku, then take a street car to Nukebenten [a small shrine], and into the dojo, where Ueshiba Sensei appears and performs various techniques. I have a number of these “movies” or visualizations in my mind. If it’s ikkyo, it includes all the possible applications, variations, and countertechniques. This sort of thing has always been a matter of common sense for budo practitioners.

The term “image training” is often used, but this is originally an Eastern concept. It’s a form of meditation. You can’t really expect much effect without identifying with what you are visualizing. You must melt into the landscape. Then you can hear the sounds of O-Sensei’s techniques and his breathing.

The term “image training” is often used, but this is originally an Eastern concept. It’s a form of meditation. You can’t really expect much effect without identifying with what you are visualizing. You must melt into the landscape. Then you can hear the sounds of O-Sensei’s techniques and his breathing.

It is said that when O-Sensei was in his fifties, his techniques bubbled forth like water from a spring. He was no longer teaching the forms of Daito-ryu as he had learned them from Sokaku Takeda. All of his life experiences, from as far back as his childhood, culminated in a continuous stream of new movements “bubbling forth as if from a spring,” as O-Sensei himself used to say. It was a form of continuous invention and discovery.

O-Sensei said that when he was in best form, an image of his opponent flying through the air would appear before his eyes; the next instant his body would move automatically and the image would become reality.

Do you consciously make an effort to pass on to your students your memories of O-Sensei and the things you learned from him?

Yes, of course, but many of the stories and anecdotes about Ueshiba Sensei are really from “the top of the mountain,” so to speak, so they are prone to be misunderstood unless their whole context is explained. On the other hand, it has long been said that knowing too many things may impede real understanding. When we were learning from O-Sensei we tried as hard as we could to absorb and digest everything, trying for years to copy him.

We have an expression in Japanese, “gokui ni kabureru,” to describe someone who attempts to exceed his ability, and this is something that the Japanese always dislike. Therefore, one should be careful when telling young people about O-Sensei, or when showing videos of him. O-Sensei used to scold us severely if we just imitated his techniques, saying, ‘You mustn’t merely imitate the outer form of what I do! Concentrate more on your basics!”

Also, we have the words “Aiki is Love.” We usually use the word love in a relative sense, saying, “I love this or that,” but Sensei spoke about “Love” in an absolute sense, as the mind of the universe. Consequently, while we may understand this “Love” on an intellectual level, without becoming one with the universe as Sensei did, we really can’t understand it as he did. Perhaps this is the “clarity” or “‘becoming clear” of which O-Sensei spoke. Of course, these expressions have religious meanings as well. O-Sensei’s talks were on a very high level and very difficult, indeed.

Regarding ki cultivation training, it is simple enough for one to realize one’s physical limitations. It is impossible to lift extraordinarily heavy objects or to run extremely fast. When delving into the realm of the mind, however, in the beginning it is impossible to know one’s true limitations or to know how to go about developing oneself. One has no recourse but to follow the wisdom of the ages as closely as possible, training diligently in the methods one has been taught.

It’s a delicate area, with the need to train in a rational, scientific manner while maintaining important traditional teachings such as the cultivation of ki.

I would like to thank you very much for your time today in helping to reconfirm some of the deeper aspects of aikido.

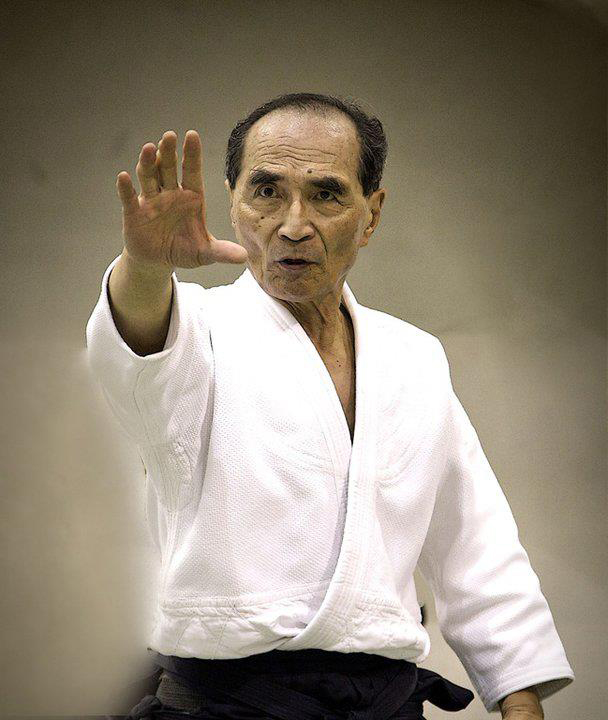

Profile of Hiroshi Tada Shihan

Born December 1929 in Tokyo. Enrolled in the Ueshiba dojo while a student of the Law Department at Waseda University. After graduation in 1952, he decided to become a specialist in aikido and a researcher of Japanese martial arts history. Currently a 9th dan shihan at the Aikido Hombu dojo, he also teaches at the Self Defense Agency, Gakushuin University, Keio University, Waseda University, Gessoji Temple in Kichijoji, and at his own dojo in Jiyugaoka, Tokyo.

In 1964 he began to travel to various locations in Europe to conduct training and instruction and to spread aikido. He established the Traditional Japanese Culture Association/Italian Aikikai in which he holds the post of Chairman Shihan. Returned to Japan in 1970 and has since made many teaching trips to Europe.

Impressive, interesting and enlightening, of real value to anyone studying aikido. A worthy interview by two worthy men. Thank you.

Oh, cool

O’sensei

Ichikukai

Tempukai

NOT Koichi Tohei

=)