This piece was originally contributed by Ken Teshima in 2014.

As I sit here writing my paper, I am contemplating the Judo tournament I competed in recently. I was eliminated early in a pool of talented Judoka, and what is the usual post-tournament ritual, I ponder all the things that worked, and things that didn’t. There is, of course, disappointment in losing, but there is also much positive energy to get back into the dojo and continue the ongoing process of polishing these things that need improvement, and adding to my base of knowledge and experience. There is no doubt that participation in tournaments has been a key ingredient in the advancement of my skills in Judo. All body parts are intact and functional, and I will be able to continue practice without missing a beat. The advice given me by my Aikido sensei (himself an accomplished Judoka) was “don’t get hurt.” He is a man of few words, but when he speaks you best listen. Since then, I have developed a philosophy of competition (and training) of “live today to fight again tomorrow.” Through this paper, I hope to lend food for thought to my fellow budoka who study all forms of martial arts, but especially to my comrades in the Aikido world.

At a very young age, I was dragged into the dojo by my father in order to teach me discipline and keep me on the straight path. He was an Aikido teacher who had many mishaps as a youth which ended taking his life in a negative direction; one that he did not want me to follow, and felt that the teachings of Aikido would help me to build the internal fortitude and character necessary to live a more positive life than he.

Aikido came to the US through Hawaii, and it was during my youth of the 60s and 70s that Aikido in Hawaii was at its peak. Senseis then were recruited from other disciplines like Kendo, Karate, and Judo. We trained so hard in those days, and I was many times in tears from being thrown, punched, kicked, or just being exhausted. Sensei would have no pity for anyone, and would get mad if you gave up. In spite of what many people today would judge to be abusive, this was how budo was taught back then. I knew that he had a genuine concern for my well-being, however, and that he was being tough because it was going to make me stronger and a better person.

Based on my journey thus far as a Judo competitor and the extensive randori training in my Aikido, Judo, and Karate curriculum, I have developed my own thoughts and opinions which I want to share regarding the pros and cons of “Competition” and how it fits (and doesn’t fit) into a Budo curriculum.

Although there were no tournaments in Aikido then, every practice was a challenge to get through, as there was a healthy “competitive” air in the dojo where no one got off easy. Attacks were sincere and without cooperation (but measured). And techniques had to work under these adverse conditions. This sort of training made us tough, both physically and mentally, and prepared us for life’s challenges outside of the dojo. Whether it was facing up to a bully in school, saying “no” to negative peer pressure, being able to focus and concentrate in an exam, or dealing with a variety of life’s obstacles as I got older, the training I received as a child stayed with me throughout my life and lives deep within my soul. This kind of training instilled a strong sense of determination and an ability to persevere when times got really tough.

Fast forward 40 years to 2014, and the martial arts world has changed significantly. The traditional martial arts schools where hard training combined with the development of a strong moral character are now an endangered species. Most traditional teachings are being lost to a trend towards training for the purpose of winning in competitions or schools have become commercialized as a business feeding on a society consumed by “looking good,” superficial motivations, and the need for immediate gratification. The net result is the giving of ranks prematurely to keep students, black belt contracts for children, and an overall degradation in the class, quality and honor associated with a true martial art school for the sake of convenience and financial survival.

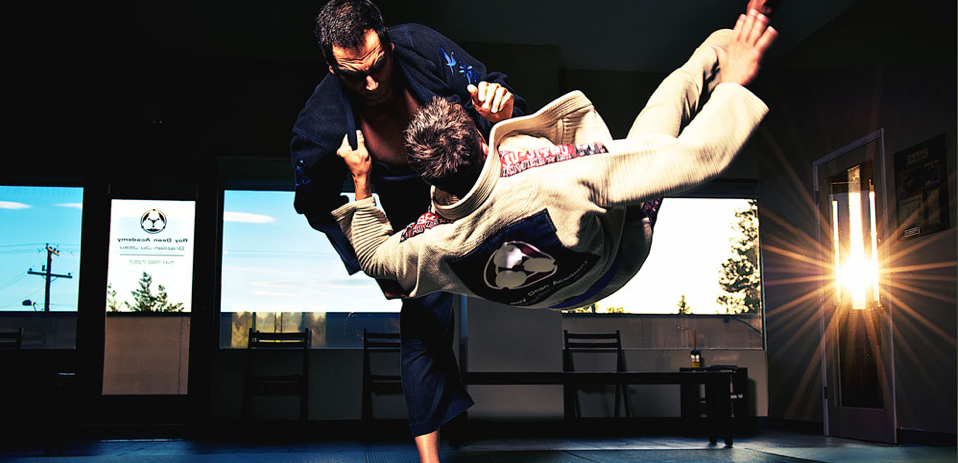

Judo, Karate, Kendo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Taekwondo, MMA, and even Aikido have developed their own brands of competition. A whole infrastructure of rules, governing bodies, tournaments, rankings, financial incentives, trophies, and titles have been created to support this movement (with Taekwondo and Judo at the pinnacle being Olympic events). The introduction of competition into traditional martial arts has turned most of them essentially into a sport, and most schools can no longer claim that they study budo anymore.

I have now been several years on a journey outside my dojo to study Karate and Judo, in addition to, and as a part of my Aikido training. Mixed into this is also some training in Brazilian Jiu-jitsu.

“There is a price to pay for going down this path, and the potential damage goes beyond the physical damage that can occur. Training like this requires time away from work and from family.”

Kaizen (改善) is the Japanese concept for “improvement” or “change for the best” which refers to the philosophy that focuses upon the continuous improvement of processes. Like in budo, an accomplishment is never considered to be the final answer as there is always something better that can be developed and new discoveries made if one keeps searching for answers by constantly asking questions. According to this philosophy, if one simply repeats mindlessly over and over what has been handed down, evolution stops and the world by its own natural process makes the art obsolete. (The very finest of buggy whip craftsmen have long gone out of business.) The core principle inside of kaizen is genchi genbutsu (現地現物) which means “go and see” for yourself. It suggests that in order to truly understand a situation one needs to go to gemba (現場), or to the “real place” where the work is done. In the dojo, we call this “kenkyu” or research. “Knowing is doing” and the best way to understand something is to experience it on your own.

Based on my journey thus far as a Judo competitor and the extensive randori training in my Aikido, Judo, and Karate curriculum, I have developed my own thoughts and opinions which I want to share regarding the pros and cons of “competition” and how it fits (and doesn’t fit) into a budo curriculum.

The short answer is that I am torn by the positive and negative ramifications of including competition into our budo study. There are many positive reasons how competition can complement our training, but by its very nature (almost like a virus) it has a tendency to infect the human psyche and cause an imbalance in the root thoughts, intentions, and motivations of the whole community. The purpose of one’s study takes a detour from self-discovery and improvement where one becomes intoxicated by the lust for winning; chasing titles, trophies, fame, and glory in order to feed one’s ego. Rather than using tournaments as a tool to enhance one’s training, the tournaments become the purpose and the end game is achieving the fame and notoriety of being the champion with the medal or the big payday.

Playing with the rules to win becomes the focus and breeds some techniques that would be dangerous if used when defending against a real attacker wanting to cause you harm. There are a set of skills and muscle memory that only works in a tournament setting that we need to be wary of. It is understandable that rules need to be instituted for safety purposes. However, it also becomes a Pandora’s Box once rules are implemented as clever coaches learn how to manipulate rules to create winning techniques. It is because of inventive minds focused only on winning the match that these types of techniques have evolved. In a real fight for one’s life, points don’t count.

On the other end of the scale, a similar caution would be applicable to those who study kata only and perform choreographed techniques with a cooperative partner. There is a lack of mental and physical preparedness for the intense conflict from a real attacker without some form of competition-like training. I believe it is unreasonable to think that one will be able to deal with anything like this unless it is practiced to a certain extent in class.

“Although there were no tournaments in Aikido then, every practice was a challenge to get through, as there was a healthy “competitive” air in the dojo where no one got off easy. Attacks were sincere and without cooperation (but measured).”

Aside from safety reasons, there are rules that are created to produce a certain desired look and feel. For example, in Judo we can no longer touch the legs at all, whether to throw or to block an attempted throw against us. This makes it easier to come in and do big throws without the fear of being countered, making for a more exciting spectator sport, and stopping the encroachment of wrestlers and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu players from influencing the direction of Judo.

Although limited by rules, the tournament ring is still the best laboratory to test your skills and techniques that you are developing in class. It is a venue where one is under the pressure of the event with a team of referees, scoring table, peers, teachers, and spectators all watching; and you are facing an opponent you don’t know who will be doing his/her best to defeat you. As a result, one builds confidence and moral character by having to put forth a sincere effort to defeat the opponent in battle while maintaining composure and decorum before and after the match. These are the positive benefits that can be derived from this kind of venue, testing one’s skills as well as one’s mental balance in the heat of competition.

It is important to understand the pitfalls of fighting within a set of rules and to find ways to train to distance yourself from the mindset and tunnel vision that will be ingrained into your psyche, not to mention the temptation to become a medal chaser and lose your budo spirit to a sports mentality. It is not easy to develop the discipline and maturity to sift through the land mines and harvest only the gems.

I have come to the realization that we must respect physics, and that oil and vinegar will not bond indefinitely. Mixed vigorously, it will produce a delicious salad dressing. But left alone for a few minutes, nature takes over. I believe this relationship to be true between competition and budo. With the understanding that the two cannot live harmoniously in the same space, how is it that we can create a delicious dressing to complement our budo salad? This is the challenge, I believe.

Webster’s Dictionary defines competition as: “the act or process of trying to get or win something (such as a prize or a higher level of success) that someone else is also trying to get or win; a contest between rivals.” I offer an alternative budo definition to competition as follows: “The act of doing one’s best to defeat another in a contest of skill (as an integral part of one’s training) where the objective is mutual welfare and prosperity, and to do so with respect, honor, and dignity for others.”

I often say to other students who compete or who are thinking about it that winning or losing does not matter, because it is the experience of going there and confronting the situation (and doing your best under the circumstances) which has rewards in itself. One learns to win or lose with a winning attitude. The development of this balance of courage, determination, humility and kindness is what will make you a better person and will help you through life’s difficulties. Along these lines, my mother-in-law shared with me an old Japanese kotowaza (aphorism) – さんか すること に いぎがある。(sanka suru koto ni igi ga aru- “There is meaning in just showing up”.)

“Most traditional teachings are being lost to a trend towards training for the purpose of winning in competitions or schools have become commercialized as a business feeding on a society consumed by “looking good,” superficial motivations, and the need for immediate gratification.”

I believe the antidote to the “virus” of competition is to make sure one has a strong foundation in the philosophy of the true path of budo. This requires extensive and continual work on basics, as this is where the core of the art is rooted. Meditation, performing kata, and the drilling of techniques is a way to reinforce this foundation. “The devil is in the details,” and it is in the sweat and toil of polishing of our basics that we discover many new things to progress the art and allows it to evolve, as we as individuals evolve with it. Competition is the sand we put into the oyster to create the necessary irritation so that a beautiful pearl will eventually emerge. If we only stay with basics (and rely on kata as the final answer), then we stop growing and we become obsolete buggy whip craftsmen. Conversely, if we do not come back to basics, we will lose our foundational roots and become wandering ships lost at sea. There is a balance in there somewhere, I believe, where we should strive to live by the spirit of budo with an eye towards improvement and innovation to make things better (using competition and tournaments as a tool), while staying grounded in our basics, respecting and paying homage to those before us who paved the way. For it is this lineage and honor we give to our ancestors that lays the fertile soil for our children and the next generation of budoka.

Warning

I’d like to wrap up my report with a warning sign on it, “Shake well before using; highly combustible if shaken too hard.” For those of you inspired to follow my path to cross train in other arts with tournament style competition, be careful what you wish for. A lot of hard work, focus, dedication and balance is required in order to be successful, leaving little room for error. For most, you will be starting at a white belt level so progress will be slow, and you must also be mentally prepared to take off your black belt and start with an empty rice bowl.

If you are not already training at least three days a week in your current dojo, in addition to clinics, camps, and other dojo activities, then you have not reached the minimum requirement to even consider this path, as you are still at a recreational level. Consider that you need to add your second discipline on top of your core discipline, that you must train at least 2 days per week in that discipline, then you can begin to see the time commitment required for this endeavor.

“I offer an alternative Budo definition to competition as follows: “The act of doing one’s best to defeat another in a contest of skill (as an integral part of one’s training) where the objective is mutual welfare and prosperity, and to do so with respect, honor and dignity for others.”

It took me a year to get into shape and develop tournament level techniques before I entered my first Judo tournament. In the process, I burned off 25 pounds of weight. I lost my first 15 matches before I won my first match. In Judo, most students do not compete, and for those that do, they usually retire from competition or quit Judo completely after college. Hence, the only competitors to fight with at most tournaments are kids younger than my children, making it even more challenging (or discouraging, depending on your frame of mind).

I have seen many injuries result from hard training and in tournaments. It is not a matter of “if,” but “when” is it that you will be injured. This is the risk that is out there all the time. Limiting the level of damage one gets can be managed, but again this requires a disciplined and balanced state of mind. One can easily become overwhelmed with emotion, ego, and fear, becoming possessed to do something extreme that will either get yourself injured or injure your opponent. Keeping a presence of mind is important in managing one’s choices in the heat of battle.

There is a price to pay for going down this path, and the potential damage goes beyond the physical damage that can occur. Training like this requires time away from work and from family. In my case, I usually never come home before 10:00 pm during the week, and use the weekends to do extra training and get caught up on my work. So, I don’t eat dinner with the family, the kids are asleep when I get home, and I cannot work as much as I could, which ends up costing me tens of thousands of dollars of income every year.

Fortunately, my wife comes from a family of budoka, and the kids are involved in and love Judo and Karate. So by assisting with the kids’ class, we get to share this time together as a family. And when there is time on the weekends, I go out of my way to make it special. For now they tolerate daddy not being around because they see the good in me, and know that it is the result of my training.

However, I am burning the candles at both ends, and although I have a strong and determined mind, I cannot expect those around me to share these values. Rather, I consider this an unsustainable quest, and I will eventually need to carve back the level of intensity to preserve the integrity of my health, my family, and my business.

It is slippery slope climbing this mountain at my age. However, for those young ones who have the inclination (and the time and opportunity — free of the burdens of life’s responsibilities) to train every day to build a strong budo foundation, I recommend you take a chance and give it your best. It is not for everyone, and in fact there are probably very few who could or would even consider such a difficult and treacherous journey.

There are ways to create a form of healthy competition inside your own dojo, however. Including randori in your curriculum, where the throws or attacks are specified (shitei-randori) or completely random (jiyu-randori), is a way to develop the kind of spontaneous reaction needed to polish one’s techniques, awareness, and muscle memory. Randori is what is lacking in many disciplines, and in lieu of tournament competition, this is an excellent alternative.

I write this report with respect and honor to all of you studying martial arts, and do not disparage anything anyone is doing, as I know that in your hearts we all share the same vision and desires; and that is to teach our children to be strong, kind, and generous human beings of good character challenging themselves to be the best they can be, with a purpose to live a meaningful life and make a positive contribution to society.

Thank you for letting me share my thoughts and experiences. I hope that I have given you something to think about and open your minds to ways you can make your budo salad a bit more appetizing.

Friday, June 06, 2014

Excellent and a must read for all…

I would say this is the best article I have read on true Budo training. I too was a Judoka in the 1950s and beginning Aikido in 1957, as I read the article I had the feeling that Ken Teshima Sensei was writing about the early days in the 1950s with Kenshiro Abbe Sensei, the discipline and spirit was so different then.

Thank you once again for such an interesting read.

Henry Ellis

Thank you, Ken Teshima Sensei. The finest article I’ve read in a long time.

Dear Henry Sensei,

Aikido has such a beautiful culture that promotes harmony and peace for all mankind that is rooted in O Sensei’s embracing of the Omoto Religion. Kano Sensei sought to reunite Japan during the Meiji Era by reviving the spirit and culture of the Samurai and infusing this into the educational system. In the old days, the path to this kind of understanding and compassion was through very hard work in the dojo, under extreme conditions. In order to be kind, one must first be strong.

Along the way, Aikido got soft. Judo became a tournament sport and is a ship lost at sea. There is now a whole generation who are disconnected from the true Budo path. It is Sensei’s like you who remember and can revive our art, bringing it back to where it should be, teaching our youth so that they can develop it from there.

Please consider this as your fate and responsibility, and to make a positive contribution to society.

Ganbatte kudasai!!

Aloha,

Ken

Very well done Ken-San!

It’s always a pleasure to train with you!

I just saw the re-post of your article… I missed it the first time!

See you in Aug.

Thank you for a beautiful article. I too came from a school where doing forms was competitive, as in “I’ll grab you so you will have to really work to do the technique, and you’ll only finally succeed because I’ll be nice. Oh, and watch my cool fall when I finally let you throw.” v. “Yeah. You’re strong, but I can break through and then I’ll really throw you hard.” Pointless, really; but we did get strong, develop some basic understanding of techniques and learn how to fall.

For real win-lose competition I think you should go to arts which are based on it. Judo comes to mind, but there are also striking arts such as Tae Kwon-do. I came up through wrestling (and fencing, archery, marksmanship…). My present inspiration is that the critical part of aikido comes before “the bell”. Terry Dobson talked about the consent necessary for a fight using the example of Robin Hood, Little John and the bridge. Competitive matches share that element with fighting. Is fighting a valuable skill? Possibly.

Good aikido does not, at least not in my present conception of the art, share that element of consent. O Sensei said it and nobody gets it, “There is no fast and slow, the fight is over before it is begun.” I’m not even sure I “get it”. It’s too strange. But sometimes I can be it. “Be all you can be?” How about, “Be what you don’t even know you are”?

The good news is that “the Way is in training” (Musashi). “There’s nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9) I feel fortunate that my teachers were mostly in the Saito-Iwama lineage. That is, as I see it, an aikido equivalent of Musashi’s Ground Book. This is not to disparage other schools. “Each man trains as he feels inclined.” (Musashi) It has worked for me. That is to say, I have persisted for over 40 years now and when I finish this will train for a bit before bed.

I think about the very high attrition rate in schools and have to concede that it isn’t for everybody. In fact, if you take a look around, a martial path of any sort isn’t for everybody. As several of us were sitting in a restaurant for Saturday lunch after Rowell Sensei’s class I noticed that we ten or so out of the fifty or more in the restaurant were the only ones ignoring the sports on the big screen televisions. But for those who are called, the Way is in training.

Iwama style is excellent to acquire as a path of an efficient Aikido 👍🏻

I congratulate Ken Teshima Sensei for a well written article that contrasts the benefits and pitfalls of modern competition with classical, non-competitve training, specifically as it relates to aikido. I’ve done aikido for 45 years (teaching professionally for the last 35) and have been studying BJJ for the last 20 years. Additionally I cross-trained in western boxing, tae kwon do and judo. I couldn’t agree more with Ken when he says that the rigors of cross-training and the commitment of time and resources involved are way more than most martial art students are willing to sacrifice, not to mention the increased risk of injury. I understand this, first hand as I am now struggling with low back and hip problems that I believe I wouldn’t have if I had just stuck to classical aikido practice. Regardless of my injuries, it has meant much to me, on the deepest level, to do BJJ along side aikido. It has nourished my spirit in ways that I find hard to put into words. I don’t regret a moment of my time doing BJJ. If I can rehabilitate from my back and hip issues, I’ll be back at it again.

One point that Ken makes that I think is particularly worth emphasizing is that this type of training is not supportive of a “well-balanced lifestyle”. Ken makes the point that the type of training he has embarked on requires quite a bit of sacrifice in terms of family and work life. I would add that it wipes out time for other “hobbies”. Gary Keller in his book, “The One Thing” states that nothing extraordinary gets accomplished by a well-balanced lifestyle. Surgeons, classical musicians, professional athletes and high-level martial artists need to spend a period in their lives, being fanatical about their training, almost to the exclusion of anything else in their lives. I like how Ken draws a line by saying that less than 3 days a week is “recreational practice”. I’m sure that Ken agrees with me when I say that there is nothing wrong with recreational practice. At the end of the day every practitioner and teacher of aikido, BJJ, Judo or any other martial art has to be clear about what they want out of practice and adjust their training accordingly.

Ok I love this article. So much in here.

Good morning Ken-san:

Thank you very much for sharing your insightful thoughts.

Great article from someone with strong spirit and discipline.

What you say is very true. Much to think about and each of us to plan our own path.

Personally, I think competition is a good part of practice, especially in the early years of our training but true Budo training should be the most important focus as we develop and age.

Mochizuki Sensei’s mission, carried on by his student, Patrick Augé Sensei is just that.

Thank you,

Judo was my first art. Aikido was my third art and I started it because I was chasing an odd form of strength that I’ve felt in a couple of Aikido dans from Hombu Dojo. Long story short (and bear in mind that I have a typical engineers’ passion for details), there is an odd sort of strength and it takes (1.) learning how it’s done and then (2.) a lot of dedication to develop it. Breathing exercises, many exercises like fune kogi undo, kokyu ho, and so on. The point I’m getting to is that it’s very difficult to get the information to learn this type of body mechanics, yet if we don’t learn these body mechanics it is not really Aikido. If you’re going to go compete with something similar to Aikido but lacking it’s essence, what have you proved?

Bravo 👏🏼

The purpose of Shiai (competition) is to cultivate, develop and strengthen character on the Path of Mutually Beneficial Coexistence.

Patrick Augé (- based on Mochizuki Minoru Sensei’s teachings)