In the final installment of this interview, Haruo Matsuoka Sensei talks about the teacher/student relationship and Stanley Pranin Sensei describes his mission to help aikido practitioners build a stronger direct connection to O-Sensei. For Part 3, read here; for Part 1, read here.

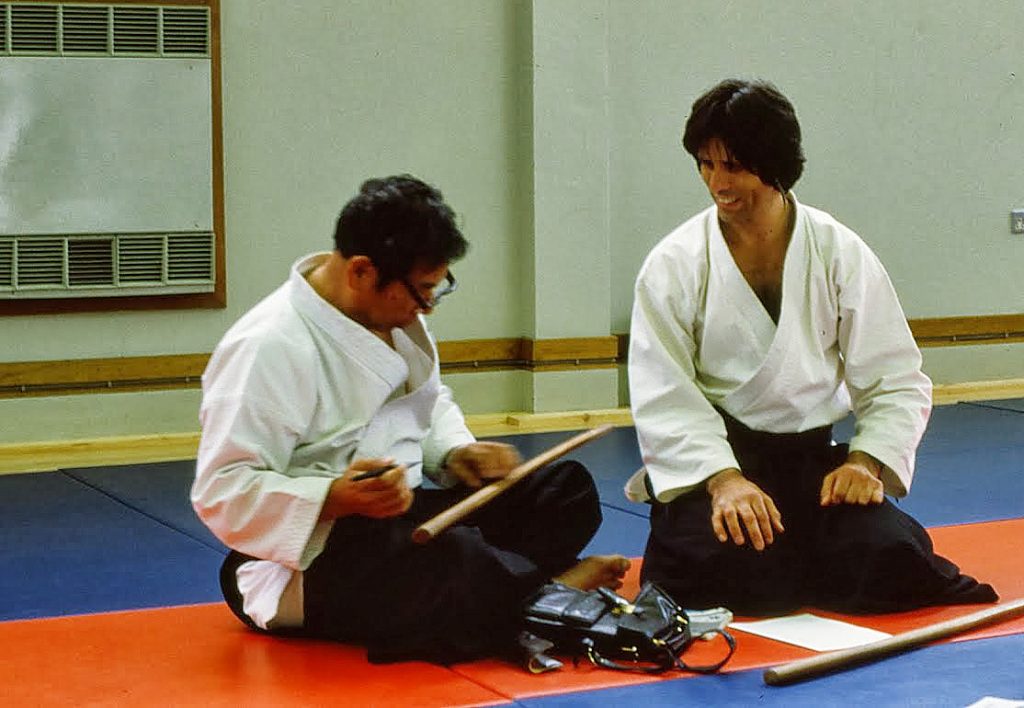

Pranin: Sensei, during the break we were talking about the fact that some people might be interested in finding out how you think about teaching your students. What’s your approach?

Matsuoka: I have to deal with many classes, but as time goes by, I can somehow see the results. Like Josh [Gold], for example. I met him in 1991. It’s miraculous. And not only him, but many other students have followed me for a long time. I just want to focus myself on seeking, finding out something new, and sharing with each person. Even in a large class I focus person to person and think about the individual. I just want to share. I need people to share. My students help me in this way. And beyond that, we all share in the struggle of developing ourselves and seeking our journey.

Pranin: I understand exactly. It’s a special kind of community. So like you say, you can’t do anything without your students. You need them to give you feedback. And as you assist them, they’ll help you in your life too, and give you advice, and correct your English, and you correct their Japanese! It’s an exchange, it’s a beautiful exchange. And it goes on and on, and you have people you met early, or mid-course. Sometimes they go away, and you never see them again. Sometimes they come back after ten years. So it’s like a journey. You stop at a destination, different people arrive, and different people leave, and you continue to evolve. It’s kind of like that.

Matsuoka: I was wondering, what have you been focusing on recently yourself?

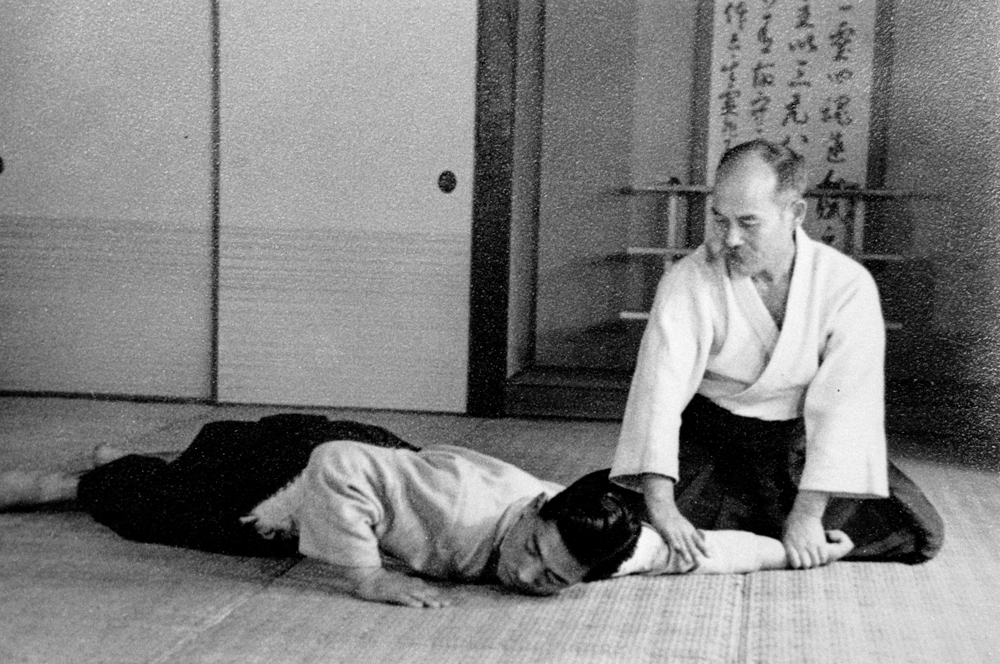

Pranin: At this point, I’m in my 54th year of Aikido. And of course about 20 of those years were spent in Japan where I had the chance to meet many of the people close to O-Sensei, many of the famous teachers, including my own teacher Morihiro Saito Sensei. I had numerous opportunities to spend time with him. One of the things that I realized over time was that due to the circumstances of the war, and how the Aikikai had to continue their activities after the war, was that somehow O-Sensei’s Aikido was never transferred to the postwar generation. I’m referring to the technical standpoint, but also his spiritual message, his way of thinking, the images that he used to express his thoughts. Most of his students didn’t understand the Omoto imagery, or O-Sensei’s metaphors, or writings.

And because of the destruction of the war, and the poverty in Japan, we don’t have films from the late 1940s and early 50s. We have very little documentation from that period. Later, we have some films from the period when Japan began to recover, and become strong as a country. But at that time, O-Sensei was an older person, and also we know that he was suffering from cancer, so it affected his physical and mental health.

So my observation is that the important parts of O-Sensei’s art, thinking, philosophy, and technique, were never transferred directly to the new generation. They got maybe second-hand or third-hand interpretations. And it was these interpretations that spread out all over the world.

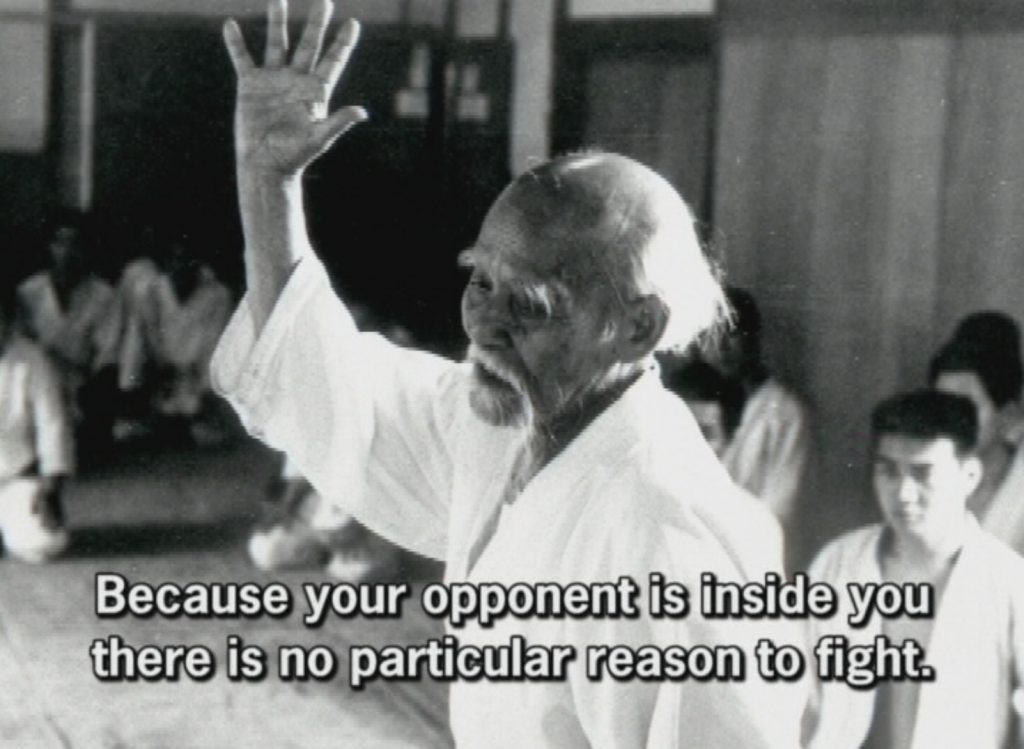

We all have pictures of O-Sensei in our dojos. But unless you do some reading, and have interest in historical matters, you probably don’t really understand his life. You won’t know what he went through, his challenges, how he faced death on several occasions, how he saw the beginnings of warfare, how the war progressed, and what Japan was doing politically.

He saw this whole thing emerge, and then this period of crisis of the eight years of war, and then the aftermath. He saw this whole cycle. I know that very profoundly affected his thinking, because his postwar and prewar thinking and expression were quite different.

So the beautiful parts of O-Sensei’s ideas, the originality, the innovation, partially are due to the destruction of war, and the impression that it left on him. And if people attempt to understand the Aikido message without understanding the importance and the impact of war, it will be hard to grasp the main themes. For example, why did he prohibit competition? Why did he become angry at Tomiki Sensei for creating a competitive form of aikido? Because he was associating competition with warfare. What does warfare produce? Well, the Pacific War showed us the answer. He didn’t want that. He wanted his Aikido to be life-giving.

It’s about the destructive sword versus the life giving sword, or constructive sword (Katsujinken), and I think that that’s the core of the message. But the people who came after O-Sensei, the famous teachers, really couldn’t express that message in a complete way. So I feel like sometimes I am an archaeologist searching and digging out old things so that I can try to understand what he went through, what he was trying to say, and put it in terms that people can understand. But to respect his vision, respect his ideas… I think that the understanding of Morihei Ueshiba that most of us have is through a layer of interpretation. One of the reasons for this (I found from my research) is that we don’t even have original, authentic Japanese texts to work with. Many of what became the writings of O-Sensei, were based on tape recordings. So O-Sensei would maybe sit in a dojo, or he would talk in front of a group of people and they would have a tape recorder – a reel-to-reel tape recorder — and record the lecture.

Then people like Masatake Fujita Sensei, Sadateru Arikawa Sensei, and Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei would transcribe what O-Sensei was saying. If they found words and images that the Japanese could not understand they would remove them. Maybe O-Sensei gave the name of a kami (deity) of which there are many,,but the transcribers would just say “kami”. So they took his language, and put it in a different context. Then that became a basis for English translations. And then the English became the basis for French, German, Spanish, Italian, and so forth.

So really we’re maybe three or four layers removed from O-Sensei. Of course there will be a dilution, a watering down of the message. And the written translations we have are not based on his actual words to begin with. We’re starting with an edited Japanese version with no mention of the fact that O-Sensei’s speech has been modified. Then that becomes translated once, or twice, or three times. So who knows what’s going to be left at the end?

So my idea is this. I have several hours of audio recordings of O-Sensei. If I take that to start with, at least I know exactly what he was saying. It’s hard to understand, and some things you can’t understand.

But I want to recover as many things as possible directly from the founder, and get these texts out there. And then the same thing technically. In that regard, we have to go back to the Asahi News film, the Noma Dojo photographs, the Budo book, and so forth.

The Aikido that O-Sensei was teaching to Saito Sensei in Iwama can help us a lot too. The idea is to bring this information forward for people who are interested in these topics, so that they can have some kind of direct connection with O-Sensei, not always through one, two, three, four intermediaries. That’s one of my goals personally.

Add comment