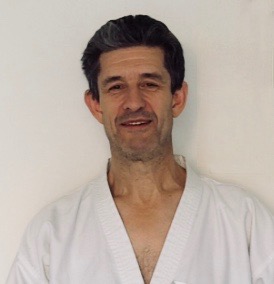

An interesting perspective on kiai and audio vs. visual perception times from Tom Collings, a long time colleague of Stanley Pranin and veteran aikidoka.

Tom began martial arts training with karate in the 1960s and started aikido in the early-1970s. After earning his aikido black belt in New York, he spent three years training at the Aikido Hombu, Tokyo, and Iwama.

Tom began martial arts training with karate in the 1960s and started aikido in the early-1970s. After earning his aikido black belt in New York, he spent three years training at the Aikido Hombu, Tokyo, and Iwama.

For 26 years, he worked for the NY State Corrections Department where his assignments included SOU – high risk parolee surveillance unit, fugitive parole violator search and apprehension, and parole officer for Level I — Violent Felony Offenders. Tom has also served as a police instructor, crisis intervention trainer, and night supervisor for a juvenile detention facility. He currently works with various security agencies in the New York area, recently assisting the Secret Service during the presidential election. He leads Aikido and Tai Chi training at the Long Island Asian Studies Center in Bellmore, New York.

I experienced an unfortunate incident in the past when a highly skilled fellow officer died after he was unable to react in time to an attack. Researching the issue of response time, I was surprised to discover the importance sound plays in reacting quickly, which shed light on how a recent aikido training injury occurred.

Research reveals that visual reaction time averages 250 milliseconds — assuming there is no freezing, panic, or hesitation on the part of the person who is being attacked. Visual perception is a relatively complex neurological process. Contrast this with auditory reaction time, which averages 170 milliseconds. Auditory perception is a more primitive survival-based sense. It is a simpler and more direct process in the brain. Seeing and hearing work best together and combined, allow response times under 150 milliseconds.

The night of the injury, I bowed in to an energetic young brown belt who is a very capable training partner. We had trained hard many times without injury. But this night, shortly after we began training, the sensei approached me requesting that I not kiai. The windows were open so “it will bother the neighbors.” I was a guest at that dojo and, like most modern aikido dojos, kiai is frowned upon. It is considered harsh and disruptive to the relaxed aikido atmosphere. I continued to train, but more quietly.

We were practicing a technique we had practiced together before safely. But this time my partner got popped — running right into my atemi. Although his nose wasn’t broken, he was seeing stars for a few moments. I felt bad and could not understand at the time why that occurred, since my partner seemed alert and attentive, and had responded safely in the past by parrying, throwing his head back, or taking a fall. Why was this time different?

Now I clearly understand what occurred. The difference in my partner’s reaction time was due to the absence of the auditory cue (kiai) to support his visual input. In other words, when both kiai and atemi were used to together, he instantly responded, but without kiai, his response was slower and less energetic.

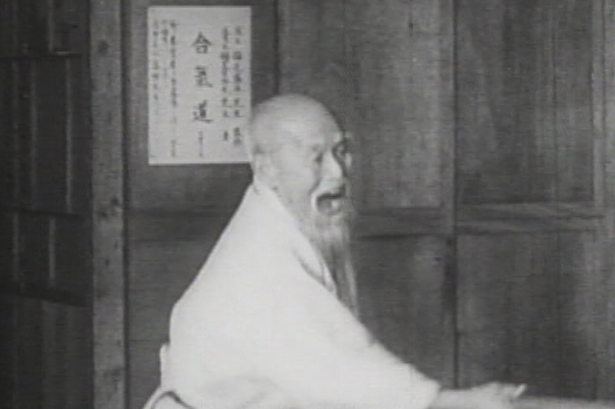

Kiai has long been recognized in martial arts and military training as an essential tool for distracting and unbalancing an attacker, as well as energizing ki flow in the body. Anyone who witnessed or has heard recordings of O-Sensei training knows how much kiai was a part of his practice. I had never realized, however, until that incident, the importance of kiai as a safety element in our training. Now if I omit kiai from my movements, I move slower, since the reaction time of my partner will be slower.

Aikido without O-Sensei’s piercing sounds is still aikido, but understand that when you remove one element of budo, you need to modify other elements (i.e. speed) or it can be dangerous.

Aikido teachers should reevaluate their attitude towards kiai, encouraging students to kiai during training, not only because of its martial value, but also because it enhances reaction time for safer training.

A special thanks to Tom Collings for sharing his perspective and experience with the community. We’d love to hear your thoughts on the subject. Please leave us a comment if you’d like to contribute to the conversation.

Tom also wrote this wonderful tribute to Stanley Pranin, founder of Aikido Journal.

As Buda said: “middle is needed” .

My opinion is senseis must ask for kiai from that energetic fellows with quick punches and leave them keep silence whom are more quiet and use to throw the fist more softly.

However, the real life threats don’t yell “kiai” before atack, and we need to be able to handle all kind of atack

I’m very surprised cause in m’y dojo I (litterally) NEVER heard about using ‘kiaï ‘ in aïkido practice.

Si far I will now probe this question in deep.

I really enjoyed Mr Collins book searching for O Sensei and find myself going back to it often for inspiration and insight on how Aikido and other Ki development disciplines can be applied to real world situations. Great Stuff!!!

Thanks for the story and insight Tom. I’m also very interested in exploring response times based on different sensory inputs. When I first started to investigate this, I was surprised to learn how slow visual input and reactions are when compared to auditory or tactile feedback and was also intrigued to learn that response times improve significantly with multiple sensory inputs. We don’t usually practice kiai in the course of our regular classes, but I most certainly see its value and place in a martial arts system. Great knowledge and perspective.

Just a couple of facts, I think, need clarification:

1) The times appear to be a little off. According to studies done on first year medical students (18-20 yr olds) in 2015 (see Jain, Bansal, Kumar, Singh: 2015), the average VRT is 190 and average ART is between 140-160. So, I am not sure where he gets 250 for VRT? His 150 for ART is closer to the mark, give or take 10 milliseconds.

When Tom says “Seeing and hearing work best together and combined, allow response times under 150 milliseconds”, I not sure what he means here, whether he is making a scientific statement (in which case what is he saying?) or offering us his own guess…

Considering, RTs are measured to distinguish the auditory response from the visual, I am not sure what’s being measured by combining them. If he’s saying that both auditory and visual response times quicken together, or synchronize, to a new quick response, this would be great news, but I’d like to see the link to the experiment he’s referring to.

2) To be honest, a quick search online shows up nothing of this kind, so I suspect this is an educated guess based on impromptu aikido dojo settings. I suppose he means that people ‘react’ much more on the mat (in a startle fashion), when he uses a kiai and atemi at the same time, as opposed to one or the other presented in a staggered way. This would certainly be something worth noting.

If this is new information though, it might even be worth sharing with the scientific community. Imagine the benefits to the people in sports where RT is crucial..!

Philosophically though, in aikido, I think it is arguable whether you want a faster response in your uke (in the dojo). There are several underlying assumptions here: A) that ART and VRT can be significantly improved. I cannot find any evidence in the scientific literature that suggests this. In fact, there is evidence to say there are gender differences, where women have slower reaction times in general. Fitter people have faster reaction times, sedentary people slower, etc. So RT is only partially changeable and there are limits.

Another assumption is the desire to have uke take ukemi automatically and therefore become more compliant. If this works, then yes, clearly it makes for a more efficient, resistance free movement. In addition, it could also be argued, as Tom begins to, that a fast(er) RT in uke is desirable to remove the chances of injury.

Yet, the way to reduce injury could be parsed in just the opposite way too. It could also be argued, for instance, that it is undesirable from an injury prevention point of view to have uke reacting unconsciously, like a puppet on a string. If uke and tori make one unit and if aikido is about “learning what it means to be human”, “what it means to love” and so on, as Ueshiba suggested, there is no reason why we cannot train consciously, mindfully cognizant of our biological reactions (of fear, anxiety, startle response, etc) while working to diminish them.

This means really looking at uke’s role in the learning process, the mutual aid and mutual growth involved, the space (ma) in between, the relationship of bodies in space, in time, under pressure of weight, gravitational pull, body-part coordination, and the sequencing thereof, not to mention all that’s going on in the head and heart. From this, what I call ‘relational point of view’, it’s better not to control uke’s reaction times but understand them for what they are.

As an Iwama style dojo, we Kiai at my dojo and are taught it’s a must. However, the story, to me, seems perhaps more about atemi than Kiai?

I’ve been in countless scenarios outside my dojo where partner obviously doesn’t use atemi, and rather awkwardly just let’s me place my fist in their face because they’re not trained to defend against it.

I’d be interested to know if the person trains with atemi; seems most dojos not using Kiai are also not using atemi or if so it’s a shadow of what it used to be.

Hard to be good at deflecting if it’s never coming at you.

(Then again, my Sensei’s always enjoyed trying to catch me off guard and pop me..)

the title of the article says it all, “Kiai as a Safety Factor in training”.

so in this instance, though the kiai and atemi are almost simultaneous, the kiai served as a forewarning of the impending atemi, albeit in milliseconds.

on the other hand, in a real fight, the kiai reaches the opponent faster, buying precious milliseconds, enough time to close-in the gap.

the growl of a tiger in the jungle can paralyse a prey long before it sees the tiger. this is infrasound, a known scientific fact. so maybe it’s about time a scientific study should be done on kiai.

On the topic of small improvements to reaction times, I recall some information coming out of Systema that peripheral vision, predominated by cones, has a more primitive and less convoluted neural pathway. This being manifested in the Systema idea of an oblique or perpendicular orientation where movement of attacker is picked up in peripheral vision. I’m not the Systema expert: so anyone who is, am I remembering correctly?

I use atemi (tori), but also train people (ukes) to avoid atemi. This takes the fear out of it. And also we use the open palm. This makes the giving and receiving of atemi less fearful. We only need to get hit once to realize we don’t want to ever get hit again. Having said that, I think atemi too, without an understanding of the harm it can cause, is useless as a learning tool. We need to know what it can do, how not to ‘overreact’ to it, and therefore know how much, precisely, we need to give in order to get the effect we are looking for. I do not need to get a startle response every time. In fact, I may wish for different and less shocking outcomes. In order to unbalance someone in multiple ways, we do not have to use atemi, only a token slap, even just the hint of a touch (but with a hidden threat behind it for back-up) is needed. It is, of course, essential to use atemi in order to get in, to close the gap, and to keep closing the gap. But, I also define ‘atemi’ in broad and narrow terms. The broad definition includes ‘talking’ to calm someone down, redirecting his or her attention, using ‘active touch’ and so on, to lead a person off-balance. My goal is to lead the person to the point where he is off-balance to the point of having to throw themselves over the edge. This requires, in my opinion, training in sensitivity, softness, active touch. Not loud atemi, which is only one aspect, when the other methods fail. For me, the central point in aikido, because of its teaching of love, must start from and aim for the subtlest level of skill and, while understanding how injury and harm can result from crude applications of technique, tries to transcend this level so that we progressively attain mastery in non-violence. Non-violence is not a belief but a skill we can get good at.

Yes, you are right. The sclera, or whites of the eyes, are designed to pick up movement. In aikido, this is often explained in terms of peripheral vision: “Don’t focus on your opponent, focus on his silhouette instead.” The iris is used to focus on things, to see or sight things in detail. The sclera takes in the blurs from the side and thus allows for rapid reactions. Therefore, it makes sense not to focus on your partner. Do you know that party trick? You point your index finger at someone’s shirt or chest region and then when they look down to see what’s there, you flick your finger up onto their chin… Hehehe… Oh, there’s another one I learned from a Circus performer with powerful arms: the hand-slap.

Hold your palm out in front of you, palm up. Get your partner to stand facing you with their palm facing down on top of yours, without touching. The idea is for you to try and slap his or her hand from above, and for them, ideally, to try and move their hand away before getting slapped.

Now, the trick is to get them to focus on their hand.

You can do this either by leading their hand with your free hand, as you place it on yours. This is ‘leading’ through touch.

When you are able to slap your friend’s hand a few times, he or she will start to look up at you puzzled. At that point, as they look at your face, they may get lucky and avoid getting slapped.

Coax him subtly to look down at the hands once more, by pointing with your free hand at the palms. If you partner looks at the hands, you will be able to slap the back of his hand every single time. Why?

Well, it turns out, in the absence of touch feedback, we rely on our eyes to sense movement (the sclera). Thus, unless the person looks directly at your face, and therefore uses the visual cues from your face or uses his peripheral movement detection (out of the corners of his eyes), he will not be able to sense your hand moving, at least moving in time.

He would be too focused (fixated) on his hand or yours through his iris. In short, his movement detector is deactivated.

This is why you can play with a person’s perceptions. Like a magician gets his audience to fixate or focus on some object, while he prepares his trick with his free hand, advanced aikidoka use this trick to lead people. Ueshiba called it “leading with your invisible sword.”

An attack is a mental fixation in a way, but it also has its physical correlates. Visual fixation is one. This is one reason why a token atemi, one which forces uke to focus on your hand, even if it isn’t actually going to cause damage, may be enough. Of course, a light touching atemi may not be enough when dealing with a trained fighter. But, again, I would argue that this is why we train: to understand what degree of distraction we need for different types of individuals. This takes experience and training. It helps to be mentored by someone who’s studied this kind of thing. My book goes into some of the fundamentals.

The Sclera do not pick up movement they have no photo receptors to allow it to do this at all. Semi-scientific knowledge is not worth spreading. Learn more about the anatomy Keni

Yes, you are right. The sclera, or whites of the eyes, are designed to pick up movement. In aikido, this is often explained in terms of peripheral vision: “Don’t focus on your opponent, focus on his silhouette instead.”

The iris is used to focus on things, to see or sight things in detail. By contrast, the sclera is designed to take in sudden movement or any kind of blurs from the side of your body and thus allows for rapid reactions (think Siber-tooth tiger jumping at your from the rear).

Therefore, it makes sense not to focus on your partner…

Do you know that party trick?

You point your index finger at someone’s shirt or chest region and then when they look down to see what’s there, you flick your finger up onto their chin… Hehehe…

Oh, there’s another one I learned from a Circus performer with powerful arms: the hand-slap game.

Hold your palm out in front of you, palm up. Get your partner to stand facing you with their palm facing down on top of yours, without the hands touching. Leave a gap between them.

The idea is for you to try and slap his or her hand from above, and for them, ideally, to try and move their hand away before getting slapped.

Now, the trick is to get them to focus on their hand.

You can do this either by leading their hand with your free hand, as you place it on yours. This is ‘leading’ through touch.

When you are able to slap the top of your friend’s hand from below a few times, he or she will start to look up at you with a puzzled look on her face. At that point, as she looks at your face, they may get lucky and avoid getting slapped, if you try to slap her hand at that point.

Coax him or her to subtly look back down at her hands once more, by pointing with your free hand at the palms. If you partner looks at the hands, and moves her gaze away from your face, you will be able to slap the back of her hand almost every single time. Why?

Well, it turns out, in the absence of touch feedback, we rely on our eyes to sense movement (the sclera). Thus, unless the person looks directly at your face, and therefore uses the visual cues from your face or uses his peripheral movement detection (out of the corners of his eyes), he will not be able to sense your hand moving, at least in time to move out of the way.

She would be too focused (fixated) on his hand or yours through her iris. In short, his movement detector is deactivated.

This is why you can play with a person’s perceptions. Like a magician who gets his audience to fixate or focus on some object in one hand, while he prepares his trick in secret with his free hand, advanced aikidoka use this trick to lead people. Ueshiba called it “leading with your invisible sword.”

An attack is a mental fixation in a way, but it also has its physical correlates. Visual fixation is one. This is one reason why a token atemi, one which forces uke to focus on your hand, even if it isn’t actually going to cause damage, may be enough.

Of course, there are exceptions. A light glancing touch-style atemi may not be enough when dealing with a trained fighter, for example. But, again, I would argue that this is why we train: to understand what degree of distraction we need for different types of individuals.

This takes experience and training and a dedication to use the minimum force necessary and to calibrate this to a lesser setting when we find more efficient means of creating the magical deception.

It helps, I think, to be mentored by someone who’s studied this kind of thing. My book goes into some of the fundamentals but few people with that degree of skill are willing to pass this knowledge on. Why give away your secrets? That’s like the greatest no-no in the magician’s trade: The first principle of a magician. Never give your secrets away or else you lose your power of magic. In aikido terms, clearly the masters know stuff. But they aren’t telling for obvious commercial, personal artistic and martial reasons. Would you give someone your favorite weapon? Only to have it used against you? Very few people can avoid the temptation of attacking their teacher or even better a random teacher they don’t know with the technique the teacher has just taught. This is obvious to anyone who has ever taught. Not everyone who trains in aikido is an angel. 😉

Very interesting conversations, I would only like to add that we do Not see thru the sclera or the “white of the eye”, we only see thru the pupil.

It turns out there are two pathways in the brain for audio input, the regular one, and a super-fast one. I think Tom Collings sensei’s numbers are for the regular audio path. I don’t have numbers for the super-fast one, but I understand it is about twice as fast as the normal one.

The super-fast one comes into play for people with (especially combat) post traumatic stress injury. It’s why they react to sounds so quickly, without being able to control it. Presumably it is a survival instinct (or something like that) left over from evolution long ago to help with emergency situations.

The upshot is that kiai’s can be responded to more quickly than seeing a strike, hence more safety. A good observation.

I exhale audibly during the point of peak exertion when training on the mat. The other day another student pointed out to me that I do this and I said, “You know why, right? Because I started my martial arts training in judo and Danzan ryu jujitsu, and in both styles they’d bark at you for not doing kiai. It’s habit now.”

I never thought much about kiai beyond its role in helping to expel air from the lungs and synchronize technique, but I learned from a different Danzan ryu instructor that he’s listening for students’ kiais as another indicator of timing.