Yoshio Sugino was a direct student of Morihei Ueshiba in the early 1930’s and opened an Aikikai-affiliated dojo by 1935. He as also a direct student of Jigoro Kano, founder of judo, and by the 1940’s was teaching kenjutsu, aikido, judo, and naginatajutsu full time. He was also a renowned action choreographer, providing sword instruction for Akira Kurosawa’s film, Seven Samurai.

This is part 2 of the Yoshio Sugino Story. Part 1 is here.

Encountering Katori Shinto-ryu on September 15, 1927, while still just 22 years old, Sugino opened his own dojo (including a bone-setting clinic) in the city of Kawasaki, where he has based most of his activities ever since. Some time after earning his 4th dan in judo, Jigoro Kano told him that he should consider pursuing some sort of kobujutsu in addition to his judo training. Judo alone was not enough, Kano said, and one could not consider oneself a complete martial artist without studying the sword. The classical tradition to which he introduced Sugino was Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu.

Katori Shinto-ryu, founded by Iizasa Choisai Ienao (Iga no Kami), had been handed down through the generations for over 500 years in the Katori area of Shimousa (now Chiba Prefecture). Considered one of the fountainheads of Japanese martial tradition, Katori Shinto-ryu had never been taught outside the Chiba region. Kano, however, asked whether some arrangement could be made to have the style taught in Tokyo as well. This caused a great stir within the school and it was discussed at length whether or not the request should be accommodated. Eventually it was decided that, as the tradition was in danger of falling into obscurity, it should be actively disseminated in Tokyo to prevent this.

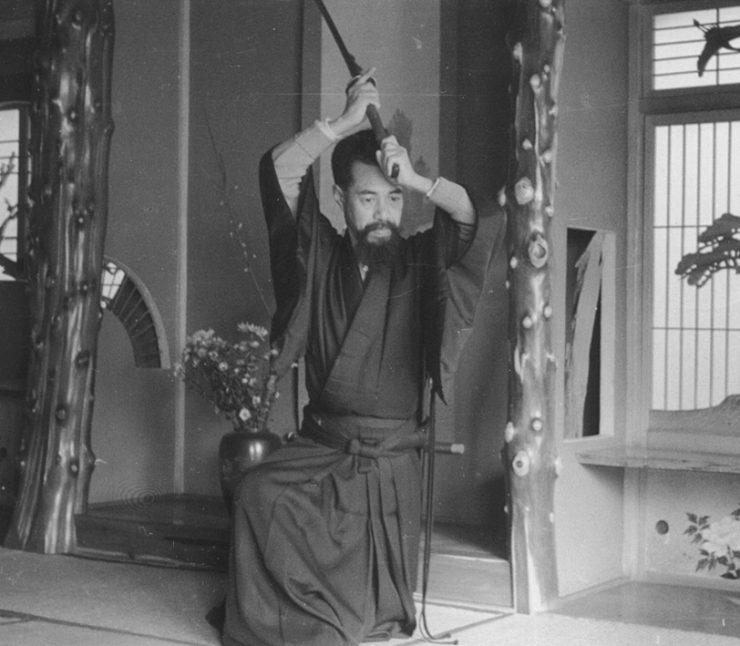

The school dispatched four shihan: Narimichi Tamai, Sozaemon Kuboki, Tanekichi Ito, and Ichizo Shiinato to teach the style at the Kodokan. It was arranged that these four should also stop in Kawasaki on their way home, training with Sugino there on Sunday afternoons and Monday mornings. Although Sugino had practiced with a shinai during his university kendo days, it was his first experience of wielding an actual sword. It was not long, however, before he had become completely engrossed in the new style of training. Katori Shinto-ryu kata tend to be longer and involve more movements than those of other classical traditions. When practicing the sword, for example, uchidachi and shidachi attack and defend back and forth in long, dynamic sets involving a whole spectrum of diverse techniques, each swordsman identifying and attacking openings in the opponent’s defenses. In this respect, Katori Shinto-ryu is somewhat distinctive among kobujutsu styles, many of which typically emphasize simpler, less elaborate movements.

Sugino began with the sword, but he also threw himself into the rest of Katori Shinto-ryu’s abundant curriculum, which includes the study of iai, bo, naginata, yari, shuriken and ryoto (two-sword) techniques.

He had no particular favorite among these, but rather went about each and every one with full enthusiasm. When asked whether, given his judo background, he felt any resistance toward the kata-only training methods of such classical traditions, Sugino said, “Budo is kata. Kata training is everything in budo. Shiai is usually written with two characters meaning ‘to meet’ and ‘to test your skill’, but in budo the term is more properly understood as the two characters (also pronounced shiai) meaning ‘to meet with death’. If you were to engage in a serious match using bokuto, either you or your opponent would surely end up dead, don’t you think? In that sense, shiai are not something you can do thoroughly and completely. When you try to talk to people about kata these days they often seem a little disappointed or disinterested. ‘Ah yes, kata…‘ they say. But treating kata so lightly is a great mistake.”

Waning Enthusiasm for Judo

Jigoro Kano had a nephew named Honda, a 6th dan who worked at the Kodokan as General Secretary. “He was one of those people who tended to make his influence felt,” Sugino recalls. One day Sugino, a 4th dan by then, boldly asked Honda whether judo had any secret principles (gokui), to which Honda replied that it did not. Sugino pressed the issue, asking again, “Really? None at all?” Honda reiterated his answer, saying no, none at all. Kodokan judo had no gokui nor any other secrets. “No gokui…” Sugino considered this deeply. Even games like go (a board game) and shogi (Japanese chess) had gokui; how could it possibly be that a bujutsu, an activity where one’s very life was at stake, had none? It didn’t make sense. “If judo has no gokui,” Sugino reflected, “is it really worth practicing?” Adding to his growing discontent with judo, Sugino had also noticed many instances in which clearly effective techniques went unnoticed or unrecognized by the referees. His enthusiasm for the art began to wane, gradually supplanted in his heart by a growing appreciation for Katori Shinto-ryu. These days judo is not taught at all in Sugino’s dojo. “Modern judo, with its weight categories and other modifications, has become nothing but a sport,” he laments. With his growing devotion to Katori Shinto-ryu, Sugino took his first steps down the path of the bujutsuka.

Sugino the Bank Employee

Sugino has often described his long life by saying, “I’ve done nothing but budo,” but in fact he did once hold a job completely unrelated to budo—as a bank employee. At the age of 20, soon after graduating from Keio University, Sugino accepted a position at the Taipei headquarters of Kanan Bank. His starting salary of 90 yen per month was exceptional considering the 30 yen normally offered to new college graduates at the time. Sugino confesses to having a bit of a secret agenda in accepting that particular position. As soon as he had the chance, he intended to transfer to the bank’s Singapore branch and enjoy life in the easy tropical climate of the Malay Peninsula.

During his sojourn in Taipei, Sugino by no means forgot about bujutsu. He trained every morning from 8:30 to 11, then put on his suit and went off to work at the bank as a deposit teller, a job connected with the detailed accounting of incoming funds. Frankly, Sugino made a poor bank employee, for he found that affairs at the bank inevitably took a back seat in his mind to his real love, martial arts. Of course, he more than compensated for his lack of enthusiasm for the work by his constant participation in local martial arts meets and competitions.

In May 1923 Sugino entered a judo competition in Taipei. He was selected as the first of five opponents to go against a third-dan judoka in a five-player elimination match. Judoka capable of making it through this sort of elimination competition are generally viewed as among the most skilled, with impressive strength and the ability to down at least five opponents in a match without too much difficulty. Perhaps deceived by Sugino’s small stature, the third-dan moved in to execute what he probably thought would be an easy inner-thigh reap, but at the last instant Sugino caught him with a lightning-fast utsurigoshi (hip shift), one of his favorite techniques. The throw had been nearly perfect, but it so surprised the referee that he became confused as to how to call it. He hesitated to stop the match since the player still had four opponents to go. Wondering why the referee had said nothing, Sugino continued the match and brought the third-dan to the mat in a strangle hold. Eventually his opponent tapped out in submission, but the referee ignored this as well. Having no other choice, Sugino continued to apply the technique until the poor fellow lost consciousness.

He was appalled at having been forced to take the match so far to be recognized as the winner. He also felt a nagging sense of having done something hateful and even disrespectful. After the match, a senior of Sugino’s judo teacher Kunisaburo Iizuka approached Sugino and said, “So, you’re Iizuka’s student, eh? I must say, the young ones at the Kodokan these days certainly don’t disappoint!” Though he accepted the praise with reserve, the young Sugino was secretly thrilled and spent the rest of the day pleased as punch, though he tried desperately not to show it.

On the other hand, while Sugino was keeping himself busy in the Taipei martial arts world, his career was not exactly taking the turns he had intended. Specifically, the transfer to Singapore that had been promised him was showing no sign of becoming a reality. Only after much discussion with his supervisor did he extract the reply that in fact the bank had no intention at all of sending him there. Knowing that it would be impossible to argue the point, he decided to quit and return to Japan immediately. The following year he opened his dojo in Kawasaki, which he named the Kodokan Judo Shugyojo (Kodokan Judo Training Hall).

Sugino’s Everyday Life

Shortly after turning 20, Sugino married a lovely young woman with whom he had fallen “head-over-heels” in love. She bore him a son, but sadly she passed away soon thereafter as a result of post-natal complications. Eventually he remarried, this time with a woman who was a distant relative, and the couple raised four more sons and two daughters. Sugino says he was a strict father, demanding that his children clean the dojo diligently when they were young and strengthen themselves through budo training when they became older. Unusually, even Sugino’s own siblings called him “Sensei,” for in many ways he seemed more like a senior instructor than an older brother. Only his younger sister Fusako, nearly 20 years his junior, has ever referred to him habitually as “elder brother.”

Sugino filled his days attending to patients at his bone setting clinic and training in the dojo. In those days, people with broken bones and other such injuries often sought treatment first at a specialist clinic like Sugino’s instead of at a regular hospital. Other doctors often referred their patients to Sugino for such treatment and the clinic prospered. Something that always surprised visitors to the Sugino household was the fact that everyone in the family spoke in an exceptionally loud voice. Of course, it was undoubtedly Sugino himself, with his own booming vocal chords, who was the cause. First-time visitors would often be led to the mistaken conclusion that the family members were arguing, when in fact this was simply their normal mode of conversation.

At any given time there were always five or six uchideshi training at the dojo morning and evening. With the addition of a second dojo in the Kawasaki area, Sugino came to have quite a few students. His approach to instruction was by no means rigid and he adjusted his instruction to the physique, strength, personality, temperament and other characteristics of each individual. He was strict, though, and not even the smallest mistake escaped his keen perception.

He would scold any who made such mistakes with a roar that echoed off the dojo walls and put the fear into everyone present (not to mention the individual who had actually committed the error). At his present age of 91, Sugino is no longer quite as vociferous as he used to be, of course, but there are still occasions when that powerful voice returns. He has been known to startle whole roomfuls of people with his ear-shattering “KAMPAI!!!” toast that comes rumbling up from his hara (lower abdomen) so that even from several meters away it seems like he is shouting by your ear. People are often shocked to find that such a voice could belong to such a seemingly frail, gentle old man. But the importance of a strong voice to Sugino can be gathered from his constant admonitions to his students that their kiai (combative shouts) are not loud enough and his obvious pleasure when someone finally manages to muster the proper volume. In any case, from his teaching in the dojo to his own training to his work in the bone setting clinic, Sugino has always pursued everything he does with a “shouting” enthusiasm and earnestness that have been consistent aspects of his personality all his life.

In contrast (but hardly surprising), he is no slouch with the pen, either. Besides being a frequent writer of letters and faithful correspondent, he has always made a habit of keeping copious notes to admonish himself of “things to do and things to avoid” in his own life and training.

Even with a few spare minutes while riding the train he could often be found writing admonishments and encouragement to himself in a notebook: “Strict with oneself, tolerant of others.” “Heaven helps those who help themselves.” “Life is falling down seven times and getting up eight.”

Even now, before giving an interview he spends considerable time the previous day preparing notes on what he would like to say and he refers to these constantly as the interview progresses. Early to bed, early to rise is Sugino’s motto and he rises every day at five in the morning for training, a custom developed through the early-morning kendo training of his student days. His diet has always been simple and without luxury. “I always try to leave the table a bit hungry,” he says. “It’s healthier that way.” He has always been fond of sake, too. “When I was young we considered it nothing at all and quite normal to drink at least three sho!” [1 sho = 1.8 liters] Perhaps a bit of an exaggeration, but in any case there is no question of his fondness for spirits of whatever sort. While these days he obviously can’t “put them away” like he used to, he is known to indulge in a drop or two now and then when the opportunity presents itself.

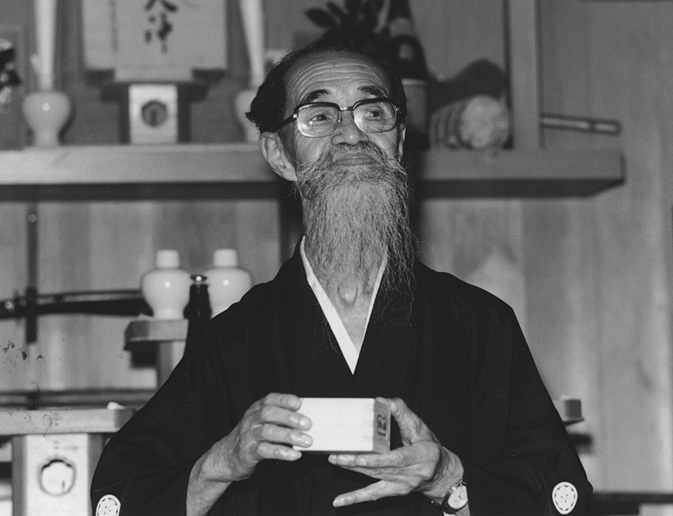

Sugino has worn his trademark long beard ever since he opened his first dojo. “I began growing it out of desperation,” he says. “Visitors to the dojo kept asking me to my apparently young-looking face to ‘please summon the master of the house.‘ I guess people didn’t think I looked old enough or distinguished enough to be the head of a household or dojo. One of my students who lived with us as a boarder suggested I grow a beard, so I took his advice.” And with the application of a little hair-growth tonic around his mouth and chin, he says, he was able to pull off a successful image change from “handsome youth” (he had even been nicknamed “Prince Regent” at the bank because of his resemblance to Prince Regent Hirohito) to “warrior.”

Sugino and Aikido

When he was 24, Sugino learned Yoshin koryu jujutsu from a well-known teacher. Around 1937 or 1938 he was that teacher’s partner in a demonstration of held in the imperial palace. There, he also demonstrated Katori Shinto-ryu with his teacher Ichizo Shiina. This budo demonstration was sponsored by the Society for the Promotion of Classical Japanese Martial Arts, an organization established a few years earlier in 1935 at the initiative of the Minister of Justice, himself a high-ranking kyudo (archery) teacher, and with the cooperation of members of the House of Councilors. Along with his teachers, Sugino had joined the new organization as a representative of the Katori Shinto-ryu. In April of the same year, the Society marked its establishment with a budo demonstration held at the Hibiya Public Hall and from then until the end of the war in 1945 it sponsored “dedication” demonstrations of classical martial arts (kobudo) at the most important Shinto shrines around Japan. Sugino participated in many of these. Sugino continued his study of Yoshin koryu jujutsu until he had reached the kyoshi level (a rank between renshi and hanshi). In judo, however, he took no further rank, despite several recommendations for promotion. “Kodokan judo had become a sport,” he says, “and I was not interested in that.”

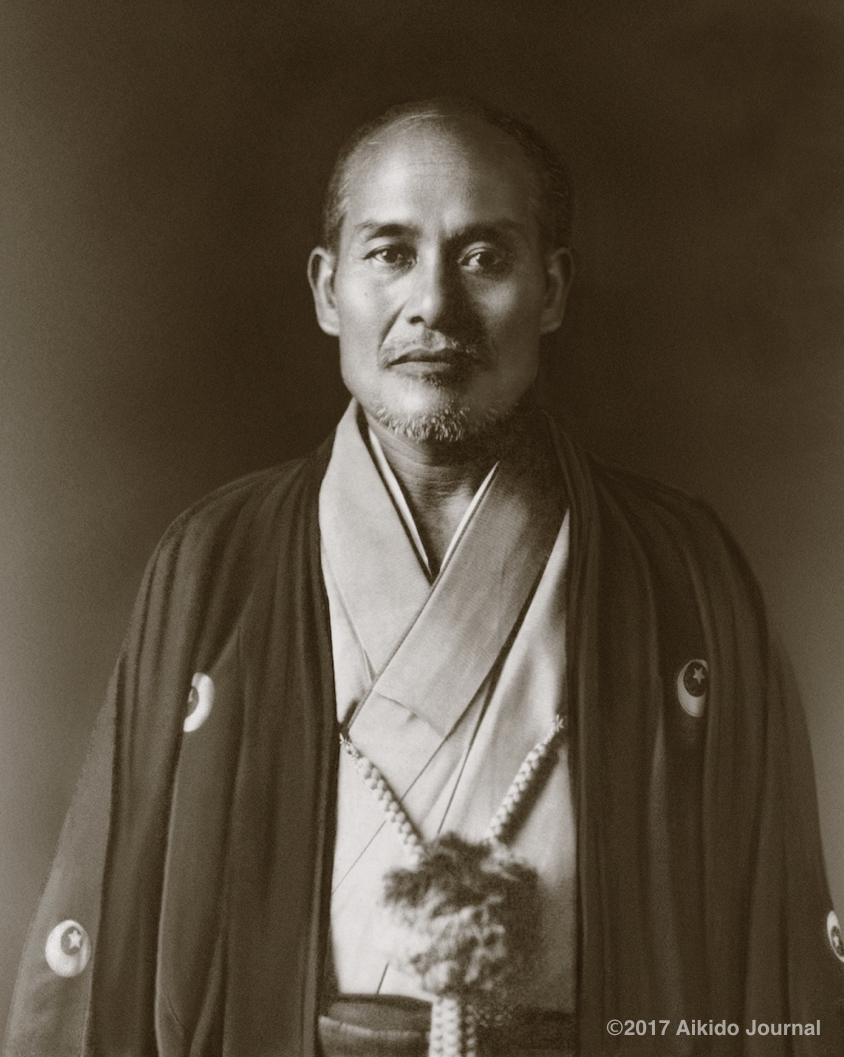

Sugino first met Morihei Ueshiba around 1931 or 1932, at the newly built Wakamatsu-cho dojo in Shinjuku. He was introduced to the founder of aikido through an acquaintance, which was the usual—and more or less essential—means in those days when it was difficult to even observe an aikido training without an introduction from a reputable individual. At the time Morihei Ueshiba was nearly 50 years old and already a well-known figure in the martial arts world.

Sugino recalls that upon their first meeting he was surprised to find before his eyes a smallish yet extremely robust man with a broad smile spanning his face. He wondered if this could really be the Ueshiba he had heard so much about.

Some two years earlier, judo founder Jigoro Kano had paid a visit to the Ueshiba dojo, accompanied by some of his students, including renowned “judo genius” Nagaoka. Watching the training, Kano is said to have remarked in admiration, “Now that is true judo!”

Nagaoka was apparently taken aback and upset by this unexpected comment and challenged his teacher by asking impulsively: “Then the judo we are practicing is not real? Is what we do at the Kodokan nothing but a lie?” Kano explained that he had not intended to imply such a thing and that he had simply meant that aikido was judo in a broad sense. He continued to praise Ueshiba and later asked him to teach some of his own students, including Minoru Mochizuki, who, in addition to having an earnest personality similar to Sugino’s, had also practiced Katori Shinto-ryu.

Sugino was already familiar with this story when he met Ueshiba. The founder began to give an impromptu demonstration of his art, which impressed Sugino with its very casualness and unpretentious manner. He watched Ueshiba’s movements intently, noting how his body seemed to be the personification of pure energy as he shifted airily about the room tossing his attackers this way and that, with the occasional pin thrown in for good measure. Back then, those lacking a deeper understanding of bujutsu tended to be deceived by the beauty and superb skill of Ueshiba’s aikido demonstrations, and would often assume they were merely prearranged. But Sugino had reached a point in his training where he was capable of easily distinguishing real martial technique from fake choreography, and he knew he was seeing the genuine article.

On this point he says: “If it isn’t so good that it makes people think it’s fake, then it’s not true aikido. Ueshiba’s techniques were truly alive, whether he was empty-handed or holding a staff or sword. You could almost ‘see’ the ki flowing from his hands.” He continues: “People like [former high-ranking sumo wrestler] Tenryu probably inwardly thought that Ueshiba Sensei’s techniques looked fake when they first saw them. But Ueshiba Sensei saw right through such doubts. To Tenryu he said, ‘Ah, Tenryu, you’re so very strong’ and slid his hand up to pat Tenryu on the shoulder. But with this simple, subtle movement he unbalanced the wrestler completely.” Impressed by Ueshiba’s demonstration, Sugino enrolled in the dojo immediately.

He recalls: “Ueshiba was always smiling or laughing cheerfully like some sort of playful god, but when it came to bujutsu he had an almost superhuman insight. “Whenever we were watching demonstrations of other martial arts he would provide his own running commentary—‘That technique was like this… Did you see that movement he just did? It was actually this kind of movement here… .‘ and so on. He understood everything that was being done, even if he was watching from a distance.” Unlike today, teachers back then did not take a particularly “student-oriented” approach and no one would have even dreamed of expecting detailed explanations of techniques. Ueshiba was no exception to this older approach. He would energetically throw out one crisp, clear technique after another without much explanation, and he never showed the same technique repeatedly. Even when his students would ask to see something again, he would simply say, “Next technique!” and do something completely different. According to Sugino, training in those days was always like that. The careful, parent-like teaching that is more or less the norm nowadays could not even have been hoped for back then and students had to be that much more earnest and work that much harder to understand.

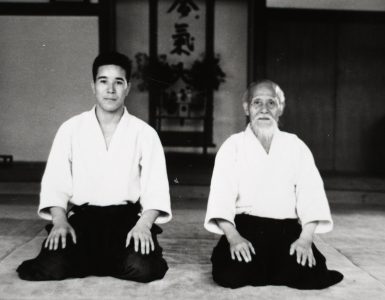

In 1935 Sugino received a teaching license from Ueshiba and after the war Sugino’s dojo became the second Aikikai branch dojo in Japan. Ueshiba’s son Kisshomaru (the present Doshu) and occasionally Ueshiba himself would go there once a month to teach. Ueshiba even asked Sugino if he would consider devoting himself professionally to aikido, but after considering his family responsibilities, Sugino reluctantly gave up the idea.

Still, the close relationship between the Sugino dojo and aikido continued even after Ueshiba’s death and even today Sugino’s students are known to do skillful aikido demonstrations.

Exquisite, fearsome techniques

While Sugino had been somewhat surprised by Ueshiba’s smallish stature, he had still been impressed by his powerful build, but the martial arts master he encountered at an Asahi News-sponsored demonstration in Osaka in 1942 was altogether different. Sugino was watching the other demonstrators as he waited his turn to take the floor. A small man standing less than 150 centimeters stepped into the demonstration area. He seemed so frail and small as to have little more strength than a child. But his gaze! … His eyes swept the crowd with a piercing glare. Sokaku Takeda.

The elderly Sokaku stood squarely in the center of the floor, glaring fiercely like one of those statues of fierce-looking, muscular guardian deities that flanking the gates of many Japanese temples. Scowling at him from across the way were his opponents, a group of powerfully built Kodokan judoka. After a hasty introduction, Sokaku began his demonstration.

One of the judoka stepped forward and suddenly launched a full-power right-handed chop directed at Sokaku’s head. Sokaku met the blow with his left hand and shifted his body. He grasped the judoka’s right hand and threw him down. “Well now! How about that?!” he shouted.

The next man moved in with another furious strike to Sokaku’s brow. This time Sokaku met the attack with his right hand, shifting and opening his posture again, seizing the attacker’s arm and pinning him easily on his back—on top of the first attacker! “Next! Come on, quickly, quickly!” The remaining judoka rushed in with similar attacks. Shifting this way and that, Sokaku avoided their strikes and put them down one by one, eventually heaping them into a pile resembling a giant cushion. All wore pained expressions as they tried to wriggle free, but Sokaku pinned them completely by holding their tangled arms lightly in a bundle with one hand.

Sugino felt a shiver up his spine—part in awe, part fear—as he watched the elderly Sokaku calmly twist his robust, high-spirited young opponents on to the ground and pin them almost effortlessly. Sokaku’s techniques clearly had nothing to do with physical power. They were, Sugino recognized, high-level applications of certain important principles and represented nothing less than the quintessence of Japanese martial arts.

By that time, Sokaku Takeda had long been a well-known figure in the Japanese martial arts world and his techniques echoed among the martial artists of the day. Sugino knew of him, of course, particularly as the Daito-ryu teacher of Morihei Ueshiba. While he never actually spoke with Sokaku directly and had seen Sokaku demonstrate on this one occasion alone, the diminutive Daito-ryu master left a vivid impression on Sugino that has remained to this day, an impression that is strangely two-fold: While he has only the highest regard for the level and quality of Sokaku’s aiki techniques, he frankly admits that he found his attitude somewhat poor, particularly in the way he would shower his opponents with taunts and jeers during his demonstration: “Well, look what happened to you!… Hey you, get up off the ground, hey?! ” And while he immobilized them with a pin from which they struggled to free themselves, he would slap them on the buttocks and say, “What a wimp, you call yourself a man?!”

Suginos friend Minoru Mochizuki told him a story about one of his own encounters with Sokaku: “Once I was minding Ueshiba Sensei’s home while he was out when Sokaku happened to come around. I served him tea, but he wouldn’t drink it. Instead, he filled another cup and ordered me to drink it first. I did and only after that did he finally drink some himself. It was the same with the cakes and everything else I served him; he wouldn’t touch any of it until I had tasted it for poison first!” Sugino reflects:

“Sokaku certainly had wonderful techniques, of that there is no question. But his attitude, well, it was really something … .”

Sugino is a veritable “living witness” to times past as he easily recalls stories about the most important martial arts figures with a clarity as if they had happened yesterday. Hearing him talk, it is easy to understand why he has come to be known as “the last swordsman.”

To be continued in Part 3…

Add comment