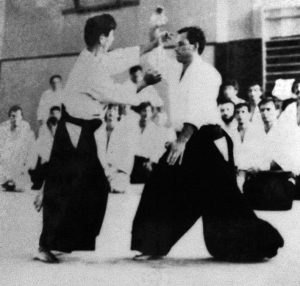

The following is a conversation between Christian Tissier and Josh Gold from March 2023. Christian Tissier Shihan (8th dan) is one of the world’s most respected and influential aikido instructors today. He began his aikido training in 1962 and moved to Tokyo in 1969 where he lived and trained at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo for 7 years. Christian Tissier was a pioneer of the French aikido community and founded Cercle Tissier in Paris, an academy that teaches aikido as well as a broad range of martial and movement arts. He was a founding member of the Fédération Française d’Aïkido Aïkibudo et Affinitaires (FFAAA), one of the two state-recognized aikido governing bodies in France and often leads major international aikido seminars and events.

Josh Gold (Aikido Journal): Good evening, Christian.Thank you for taking the time to speak with Aikido Journal again.

Christian Tissier: Yes, of course.

You just returned from leading a seminar in Germany. How often do you travel for seminars these days?

I’m traveling less these days than before. I have reduced the number of seminars I accept, especially when the location is too far or difficult to reach. When I travel to do seminars, I want to build long term relationships with people so it’s important to go to a place every year, otherwise, it makes no sense. I still have regular cities I visit, especially in Europe. Places like Germany, Holland, Italy, and Spain. In May, I will be going to Bulgaria for a seminar, and then of course San Francisco at the 11th Street Dojo.

Traveling so much must give you an informed perspective on the aikido world. Post-pandemic, how do things seem to be going?

The pandemic has affected the number of people regularly training in dojos, but seminar attendance has increased. People are hungry to practice and attend seminars again. While it’s not like before, attendance is improving, and my seminars are full.

How are things at your dojo in Paris? Can you share a little about the history of that dojo and how it’s structured now?

My dojo in Paris is also doing fine. Probably similar to most dojos after the pandemic. We have lost some students, like everyone else, but things are running very well at the moment.

In regards to the history of Cercle Tissier – I started teaching at the dojo when I returned from Japan in 1977, and I bought it in 1980, so I now own the building. I used to teach every day until I moved to the South of France in 1990. At that time, I decided to entrust the management to others. I continued to visit the dojo every week, twice a week for about 30 years. Now I visit two or three times a month for two days.

There are many different arts and disciplines that are practiced there, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, dance, and aikido, of course.

Yes, we have about 3,000 people practicing there. We have aikido, different kinds of dance, yoga, kajukenbo, boxing, jiu-jitsu, krav maga, karate, kobudo, and many other martial arts. Aikido was the main activity for a long time, but it’s not the case anymore. Maybe because I’m not there enough. The other people teaching are very good, but when you are the boss of a dojo, people prefer you to be there.

Tell me more about what it’s like to have a dojo where so many disciplines are practiced.

The land is very expensive in Paris, so we don’t have a choice. When you buy a building, you have to make enough money to make loan payments. We have four different rooms to teach at the same time. The main dojo for aikido is 200 square meters, and we have three other dojos that are 100 square meters each. We need to have four different martial arts or activities going on at the same time. It’s a big advantage because one activity can bring students to other activities.

“We have about 3,000 people practicing (at Cercle Tissier). We have aikido, different kinds of dance, yoga, kajukenbo, boxing, jiu-jitsu, krav maga, karate, kobudo, and many other martial arts.”

Do many of your aikido students cross-train in other martial arts or movement practices that are going on there?

Yes, some go to jiu-jitsu because it’s a good complement to aikido. It’s a different kind of practice, but can be very beneficial. Some of them also take karate lessons. I tell my young people, ranked sandan, yondan, or godan; if they want to become professional, they should do some karate or boxing a little bit to see something else and gain martial experience.

Aikido and many of the other arts practiced in the dojo are forms of budo. What is your perspective on the role budo can or should be playing in society? And why don’t you think Budo has been more influential in the modern world?

It’s a fact that traditional budo are declining because there are so many other options available now. People are looking for something quick and easy, but traditional budo requires discipline, a specific uniform, a clean uniform, a set class schedule, things like this. Many people don’t understand why they should do that when there are other options that are quicker, more convenient, or more practical.

Of course, we don’t propose teaching people self-defense skills quickly like krav maga. People come to aikido because they want something deeper and more unique, but we have to make it more appealing and relevant to modern society. The main purpose of budo is not just self-defense, but also personal development and growth. As teachers, we have to show how it works and how our students progress and benefit from it. I believe that if people experience the benefits of traditional budo, more people will be drawn to it.

How would you describe budo’s place in the larger universe of martial arts?

Budo is a way to perfect oneself through physical training within a set of constraints. While budo are a kind of martial art, it is important to note that not all martial arts are budo. The values and goals of budo are different from self-defense systems. Budo focuses on adding natural principles such as distance, vision, technique, communication, respect, integrity, and purity to one’s practice. The more natural principles one incorporates, the more their movement will become pure. Budo is about achieving purity in both movement and mind, and it is this pursuit of perfection that sets it apart from other types of martial arts.

“People come to aikido because they want something deeper and more unique, but we have to make it more appealing and relevant to modern society. The main purpose of budo is not just self-defense, but also personal development and growth. As teachers, we have to show how it works and how our students progress and benefit from it.”

How, specifically, do you think budo contributes to personal growth, or perhaps even something like developing leadership skills?

Budo emphasizes principles such as communication, respect, and integrity, which are essential in building strong relationships and developing leadership skills. Through budo training, individuals learn to calculate risks, push themselves to take calculated risks, and develop the discipline to persevere through challenges. These are all valuable skills that can be applied to personal and professional contexts. Moreover, the pursuit of purity in both movement and mind requires dedication, perseverance, and a willingness to learn and grow, which are all qualities of a strong leader.

What would you say to someone interested in starting budo training?

I would encourage them to find a good teacher and to approach their training with an open mind and a willingness to learn. Budo is a lifelong pursuit, and it requires discipline, dedication, and patience to progress. It is also important to note that budo is not just about physical training, but also about developing one’s character and cultivating a strong moral compass. By incorporating natural principles into one’s practice, individuals can bring about positive changes not only in their movement but also in their lives.

Generally, budo arts don’t get a lot of visibility outside of their own communities, but one area where we unfortunately see budo arts more broadly these days are on social media channels like McDojoLife. You’ll see not just aikido, but daito-ryu, Chinese or Indian martial arts, tae kwon do, and even self-defense systems. Videos are featured of teachers doing no-touch practice, or demonstrating things that seem to violate the laws of physics. In aikido, some teachers use very subtle connection exercises to teach principles. Some demonstrate things where there is no physical contact, or very light contact and the uke will fly through the air. Some of these clips are taken out of context, but some are an accurate representation of what’s happening on the mat. What are your thoughts on this kind of practice?

Well, yes, we know some aikido practitioners who have a very good background and technique. Then, at some moment, it changed a little bit and they try to explain the way it works with no-connection techniques. I can understand what they explain, but there is no longer any kind of feeling to the practice. For me, it’s a really bad way to promote what we do. People who see that will think that it’s fake. Well, because it is.

The problem is that I’m not sure that they don’t know themselves that they’re fake. I saw a video…I don’t remember the gentleman’s name but he was a Chinese martial artist who would often do no-touch techniques. He accepted a challenge fight with a karate practitioner. The first punch, he took it, and he was very surprised. This means he’s a fake and really believes in what he does. The most crazy thing is how the uke or partners also believe in that. It’s really sad when you see that.

You probably need some kind of cult-like atmosphere to develop a group of people who follow along with that kind of training without questioning what’s going on.

Yes. It’s a kind of mind manipulation and it’s very dangerous in my opinion.

On a lighter note, you have a book coming out soon. Can you tell us abit about it?

Yes, my book is currently being translated into English, and I hope it will be ready before Christmas. It’s not a technical book, but it’s a book that shows what aikido is all about. It includes 80 pages of techniques, one page for ikkyo, one for nikyo, one for sankyo, yonkyo, and two or three pages about aiki-ken and aiki-jo and tanto dori to give a basic explanation.

We have a lot of contributors who wrote some very interesting articles about different subjects related to aikido. About 20 people contributed to the book, including Guillaume Erard, Jimmy Friedman, and Bruno Gonzalez, who wrote about the connection between the situation we have in theater and the situation we have in aikido.

Did you do original photography for the book?

Yes, we shot some special photographs for the techniques, and we asked contributors to include nice pictures of their senseis. We have a lot of iconography from Japan as well. It’s not just focused on technique; it’s also a book to showcase aikido at the same time.

When is the book coming out?

I think before Christmas.

You have trained with many aikido masters, including Kisshomaru Ueshiba. Can you tell us a bit about some of your teachers and the things that most inspired you from one or two of them?

When I was in Hombu Dojo, I used to practice in my seniors’ classes. My main teachers for some very clear reasons were Kisshomaru Doshu and Yamaguchi Sensei, but I was also very close to Saotome Sensei. Before he went to the United States, we used to practice together very often, even in private. We did a lot of jo. I was also very close friends with Masuda Sensei, who was like an elder brother to me. Of course, Osawa Sensei also protected me very much, especially when I came back to France.

Doshu and Yamaguchi Sensei were my main teachers because Doshu was the Ueshiba family successor, and I loved his personality and the work he had done for aikido. Going to his class every morning, taking ukemi, and watching how he was dealing with other people helped me to learn the orthodoxy of aikido. This helped me a lot because when I came back to Europe, aikido was a little different from what I had learned in Hombu Dojo. I just said, “What I do is like that. It’s Doshu’s aikido.” That helped me very much.

With Yamaguchi Sensei, it’s completely different because his aikido was also incredible, in my opinion. The combination between both orthodoxy and something also very clear technically, but in a different approach, was a great opportunity for me.

“…Doshu was the Ueshiba family successor, and I loved his personality and the work he had done for aikido. Going to his class every morning, taking ukemi, and watching how he was dealing with other people helped me to learn the orthodoxy of aikido.”

How did you seet Yamaguchi Sensei’s aikido differing from Doshu’s?

Yamaguchi Sensei’s aikido was very different from Doshu’s. Of course, some people didn’t like it, but I was really interested in what he was doing. Yamaguchi Sensei was not someone who talked about O-Sensei. He was never saying, “O-Sensei told me to do it this way.” Because I was close to him, if I asked a question about O-Sensei, he would answer, but his answer was always that he was a different person from a different world, and that now it is a different time. Yamaguchi Sensei always respected Hombu Dojo and the Ueshiba’s family position but he didn’t answer questions or justify or explain what he was doing by using an appeal to authority.

When Yamaguchi Sensei passed away, Doshu said, “Two or three months ago, I did a demonstration and Yamaguchi Sensei was there. Yamaguchi Sensei came to me and said, ‘Your Aikido is very pure now…’” Just the fact that Doshu would share such a statement showed that he recognized Yamaguchi Sensei not as a superior, but yet as a very important person in the aikido world.

Two very different personalities, but really beautiful personalities.

Thank you for taking the time to chat with us, Sensei. I look forward to seeing you in San Francisco in May!

- If you’d like to learn more about Christian Tissier, we recommend this excellent biography by Guillaume Erard.

- Join Christian Tissier’s seminar in San Francisco, CA (May 26-28, 2023).

Nice article. It’s nice to read stories about Doshu Kisshomaru and Yamaguchi Sensei.

Thanks Josh for bringing us closer to the minds of important Budo Sensei with this interviews.

He didn’t really answer that last question–what is the difference? As a beginner, I cannot see how Yamaguchi was doing anything drastically different in technique…anyone care to elaborate? What was he doing differently?

A chat with famous Aikido instructor Christian Tissier would be a remarkable encounter full of profound insights and knowledge in the field of martial arts