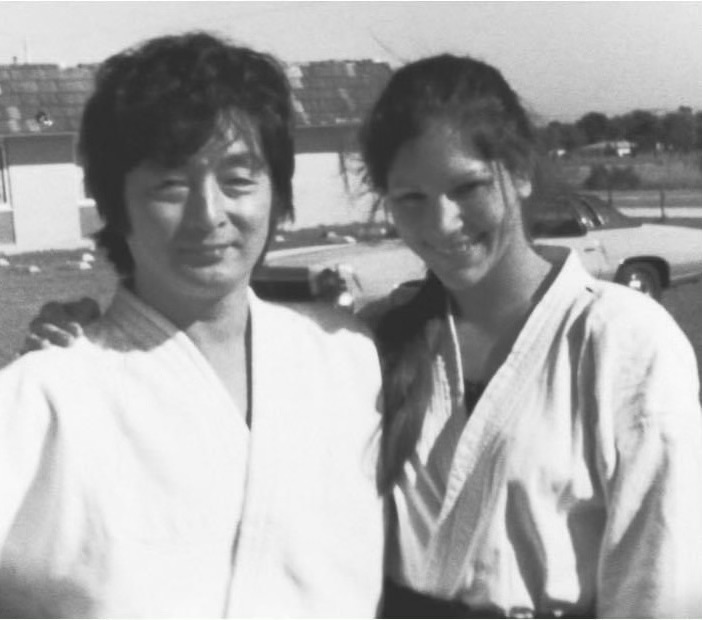

Penny Bernath Shihan holds the rank of 7th degree black belt in aikido and is a member of the technical committee for the United States Aikido Federation, the largest aikido organization in the United States. She started aikido in 1973 in Hollywood, Florida and soon after, became a student of Yoshimitsu Yamada Sensei. In her almost 50 years practicing the art, Penny has studied under many of the direct students of the founder of aikido. Penny is one of the highest ranked female aikido instructors in the United States and regularly teaches at seminars throughout the country and abroad. Along with her husband Peter Bernath, Penny runs Florida Aikikai located in Fort Lauderdale, FL.

Josh Gold: Thank you for joining us today, and congratulations on your recent appointment to the technical committee of the United States Aikido Federation (USAF).

Penny Bernath: Thank you. I am overwhelmed and thankful. I think it’s an important milestone and I’m glad to have a role on the technical committee.

The USAF Technical Committee provides instructional oversight for the largest aikido organization in the United States. Can you share a bit about the structure and function of the committee?

There are six of us on the committee. One can think of the technical committee like the chief instructors of the USAF. For example, every dojo has a chief instructor, and that instructor takes care of most of the teaching, ensures that instruction aligns with the curriculum, and makes sure everyone is on track with their testing and progression through the ranks.

Rank is ultimately important to many people in aikido so they’ll often bring their concerns to a technical committee member who can engage with them, support them, and talk to Yamada Sensei when necessary. The USAF technical committee also serves as advisors to Yamada Sensei because we all have a very long history with him.

You’re the first woman to sit on the technical committee in the history of the USAF. How do you think your perspective as a woman can positively influence that committee and / or the organization at large?

I think it’s really important that I’m here. And I’m qualified to be here and capable of handling the role well. I started training in 1973 when I was 20 years old. Since that time, I’ve never taken a long break from training, even when I had my children. My primary teachers and main influencers were direct students of O’Sensei.

I think I bring a valuable perspective to the committee and the USAF. I’ve trained for almost 50 years as a practitioner, spent decades as a dojo-cho (executive director), and travelled around the world with Yamada Sensei. I have also taught seminars around the United States and internationally. Having done all these things as a female is a different experience from that of the men on the committee. So I bring that perspective with me.

And yes, we need a female on the committee. It’s overdue. I know this art, I feel this art, I understand it, and I’m a teacher by trade, so I think I can pass aïkido on. I’m very glad to be here and look forward to contributing.

In terms of your perspective as a woman practitioner, dojo operator, and master teacher – are there any stories related to gender-specific challenges in your history in aikido that you could share?

You have a couple of hours (laughs)?

When I started aikido, my personal life was a mess. When I walked in the door of the dojo, there was all this structure. I loved that structure. And I love that there were people to respect. You took your shoes off, you bowed onto the mat, you bowed to people. The harmony, the structure, and the community are what kept me there. I wanted that.

But one thing I discovered was that part of the structure was that in class, we lined up in order of rank. And so, if I tested for 3rd kyu, for instance, I took my place, I moved up. But if six months, or even a year later, a man tested for 3rd kyu, he sat in front of me. This went on for the first eight years of my aikido experience, before Peter (Bernath) came. This made me feel that no matter how far along I got, I was never going to be at the front of the line because if a man, even if he came 10 years later than me, had my rank, he would sit in front of me. I just felt like a second-class citizen, honestly.

That’s messed up.

I know. But now, I’m a member of the technical committee and now I sit at the front of the line. So, I think it shows that aikido is moving forward and accepting the path that society is dictating. There is change.

“I’ve seen aikido change and I’ve seen my place in it change. Women need to not only be treated as equals but also be regarded as equals.”

You shared a story with me about a training experience you had decades ago at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. Are you open to sharing that?

Sure. In 1986 I went to Japan with a group from the United States. Yamada Sensei and Kanai Sensei came with us. I was very excited. One day, I wanted to train in the morning class but no one else wanted to go that day. So, I figured out the transportation and went by myself. When it was time to practice, everyone ignored me when it was time to pair up. There was only one person left without a training partner, a Japanese gentleman. He had no choice but to work with me, and he didn’t want to. He really didn’t want to acknowledge my existence.

The first technique we practiced was shomenuchi sankyo, and this man literally wouldn’t acknowledge my existence. I was a black belt at the time, but he was from Hombu Dojo so, of course, as a matter of etiquette, I attacked him first. But he wouldn’t do anything. He just ignored me when I attacked him. So I kept hitting him in the head thinking he’s got to respond. What am I supposed to do?

(Kisshomaru) Doshu was teaching the class and he came over. He was very upset at this guy for not doing the technique, so he kept showing him how to execute the movement, with me as his demonstration partner. I was thrilled about that. But this man just couldn’t do it. Doshu came back more than once and was not happy about that.

How did that make you feel?

After numerous failed attempts to get my partner to engage with me, I just wanted to shrink into nonexistence. I didn’t want to be there. I wanted to disappear.

And when I got back to the hotel, there was a message requesting that I go see Yamada Sensei immediately. I had never seen Yamada Sensei so angry. He said Doshu called him to tell him about the incident, and that I was rude and disrespectful. Some of the details of the incident didn’t come through correctly to Yamada Sensei, or were communicated from a different perspective. Yamada Sensei was furious and told me that I disrespected him and the art. I wanted to tell Yamada Sensei the details of what happened but he was too upset at that time. In the end, it was fine. However, if I was a man, this never would have happened. None of the men who went with me on that trip had any problems like that on the mat.

“I don’t want to say I love everybody I train with. I don’t. But the joyfulness that comes from a good flow of practice is amazing.”

And then, later that same year, Doshu came to the USAF summer camp. Prior to the seminar, everyone wondered who Doshu might use as uke and people specifically remarked that he never calls women as ukes. So Doshu starts the class and calls me up to be his uke. I was shocked. I literally sat there for a second not knowing what to do.

What technique did he demonstrate with you?

Shomenuchi sankyo, the same technique I was supposed to be practicing with that guy at Hombu Dojo. I must have made such an impression upon Doshu (laughs).

Why do you practice aikido? What does the art mean to you?

It’s the empowerment. I love it. I think it is a powerful exchange of energy. It’s magic. I don’t think there’s any other feeling like it. You’re throwing another human being with tremendous power and not hurting them. I don’t want to say I love everybody I train with. I don’t. But the joyfulness that comes from a good flow of practice is amazing. And so, where else are you going to get that? I think that some people miss the beauty of aikido when they try to fit it in the category of a combative sport.

Tell me about your relationship with Yamada Sensei. When did you start training under Yamada Sensei?

I was 20 years old and the dojo I trained in had only six students. My teacher approached me one day and told me that two senior aikido teachers were coming to Florida just to vacation; no aikido. He asked me to pick them up from the airport and take care of them while they were in town. I didn’t know them at all. I had just started aikido. When they got off the plane, I called them Yamada and Kanai. I didn’t even know to address them as “Sensei.” They were in their 30s and to me, they were like rock stars. They walked off that plane, and Yamada Sensei looked like Elvis Presley and Kanai Sensei was so amazingly beautiful and charismatic.

We had a great time. I brought my sister with me and we did our best to take care of Yamada Sensei and Kanai Sensei. None of us had any money so it was a very modest experience for all of us. We played some ping pong and went to the beach, but mostly they wanted to be by themselves. They were friends who wanted to hang out and spend some time together alone.

“(Yamada Sensei) always respected that I could organize things and he trusts me with financial and organizational responsibility. He opened up the aikido world to me and so I’m completely indebted to him. I am endeared to him for that.”

I feel that because I didn’t meet them on the mat, my relationship with them was forged in a completely different way. In retrospect, I believe I was quite lucky, because I was terrible at aikido at the time and instead of them knowing me in that context, we all started off our relationship as friends. Later, when I began to train under them, I’d get this feeling they were thinking, “Oh, forget it. She’s never going to get this, but she’s nice so we’ll keep her around.”

It started a long-term relationship of trust. Yamada Sensei came to Florida often after that. He liked to do seminars here.

When my first teacher moved away, Yamada Sensei actually gave me money to start our dojo and he brought Peter (Bernath) down. Yamada Sensei told me, “I’ll bring an instructor from New York, but you take care of all the organizational and business aspects of the dojo, and you report to me.” And so, when we started the dojo, Florida Aikikai, Peter and I were on equal footing with Yamada Sensei. So, it was a partnership.

And now, Yamada Sensei is his 80s. What’s your relationship with him like now, after 40 years?

Very dear. I care about him, I worry about him, and I want to see him, which the pandemic has made very difficult. He’s like my father but in a different way, and I care about him deeply.

Giving me the responsibility to organize the USAF annual winter seminar was gigantic. And if it’s because I was a woman, so be it, because it opened every door for me. He’s always respected that I could organize things and he trusts me with financial and organizational responsibility. He opened up the aikido world to me and so I’m completely indebted to him, and am endeared to him for that.

The USAF has been in the spotlight recently for gender balance and equity issues. What’s been done in the organization to address this? And, as a senior member of the USAF, what changes would you like to see implemented in the future?

I’ll say a few words on this from my personal perceptive, but please keep in mind that I’m not speaking on behalf of the USAF in an official capacity right now.

I’m now on the technical committee, and that’s huge. Yamada Sensei comes from a very Japanese background. But although we have Japanese roots, we’re a global society. And globally, women’s issues are changing. And so, in a natural sense, aikido needs to change too. And it already has. I’m a first-hand witness of that. I’ve seen aikido change and I’ve seen my place in it change. Women need to not only be treated as equals but also be regarded as equals.

There has been conflict and things have changed. And things need to continue to change. For change to happen, there has to be conflict. The question is, how do we organize that conflict in a way that produces positive outcomes?

Is there anything else you’d like to share with the Aikido Journal community?

I appreciate very much that you’ve given me the opportunity to have a voice and share my thoughts and experiences in the aikido world. I’ve been wanting to communicate these things for a long time, and never had an opportunity like this. Thank you so much.

Special thanks to Brad Edwards for providing the photography for this article.

“I’m now on the technical committee, and that’s huge. Yamada Sensei comes from a very Japanese background. But although we have Japanese roots, we’re a global society. And globally, women’s issues are changing. And so, in a natural sense, aikido needs to change too. And it already has.”

According to the New York Aikikai website, Yamada Sensei came to New York for a demonstration in 1964. Are we really celebrating the fact that it took 57 years of being in the USA for a man to overcome his “very Japanese background”?

This excuse of it “being the Japanese way” is brought up frequently in discussions about how things should be done by both people who are from Japan and not. Is this a realistic excuse for gender bias or other similar problems or just a fantasy maintained by people who should really know better?

In order to be a 7th dan and member of the technical committee, one needs decades of practice. Given that martial arts attracts more men than women, the candidate pool of women for achieving these milestones is extremely small. Good for Penny for meeting those standards and good for Yamada Sensei for not bending to the mob over this issue. We now know that any woman at that level genuinely deserves it.

Good for “Penny Berneth Sensei”, please. As a woman who has trained for 48 years like Bernath Sensei I expect some respect to be shown.

It’s a difficult thing to read and rationalise away isn’t it? But I think context is important. My natural instinct is to agree with you that it’s a convenient excuse to hide behind ‘coming from a Japanese background’.

However, I think your cultural background is enormously important. We’ve decided in the West, as a society that gender equality is now incredibly important, and rightly so in my opinion. But others in the world have not. We might criticise that but if your entire worldview, which is a product of your environment, is different from ours is it really fair to demand that they should have seen it years ago because it’s obvious to us?

Unfortunately gender equality, like anything in morality is not absolute. I wish it were, it would be much simpler!

Hi Penny, I’m glad to hear women are bringing up the issue of gender equality in aikido. I think this brings up a can of worms on all sorts of related issues including the technical curriculum within aikido that I don’t have space to elaborate on here. But, I wonder if I could ask you about the incident at Hombu where the old man paired with you ‘ignored’ you. You say you hit him on his head numerous times. It’s not clear what rank this man was. Was he a beginner..? Was he old? He sounds like he was at least older than you. In Japan, as you may know Confucianism has suffused the culture, so much so that one might equate Confucianism with Japanese culture as a whole. The terms of interaction between age groups and gendered are ordered accordingly. Women are usually more diffident, deferential, quiet, and polite, for example, than men. There’s a clear demarcation between feminine conduct and masculine. To step outside these well-worn customs is to stand out in a negative way and would invite being looked down upon, if not frowned at. The quiet and demure Japanese female is so much the ideal in Japan and has been cultivated over hundreds of years, so much so that, as you may know, the Japanese language is unique among languages in having a gender-separated twinned use of language. In short, men speaks one kind of Japanese and women another. Men stepping out to speak in the female language would also stand out. On top of that, to make things extra difficult, there are different forms of politeness. We address people formally usually until and unless we get to know them better and we are ‘permitted’ (in a way) to speak in a more familiar voice as friends. Even then though the male and female registers are strictly kept apart, unless we intended to make a joke or were prepared to sound gay. The use of formal language and the male pressure on women to use deferential speech has been relaxed to a degree in urban settings, due in no small part to feminist critique and modernization. And most people in places like Tokyo tend to speak using standard neutral Japanese, although you will find in places like aikido dojo, and in other dojos where traditional activities are pursued, traditional and formal terms of address and behavior are de rigueur. But it also occurs to me to question your behavior of hitting someone on the head multiple times when he wasn’t responding. This would seem unusual even in our society, especially enacted toward an older person male or female. I don’t want to misread your actions but what do you mean? Does ‘hit him on the head’ mean that you went to do shomenuchi and gently stopped at his forehead as most people do if somebody isn’t responding? Because we usually give people the benefit of the doubt don’t we, especially if he was a beginner? And, I am not sure what you mean by ‘didn’t acknowledge me’? What does that mean..? Do you mean he didn’t bow when you paired up..? Did you say ‘yoroshiku onegaishimasu’? Or ‘onegaeshimasu’? As one might as a newbie on the mat, especially when training with an older person, who, as you may know, is used to deferential treatment in Japan? Do you mean he didn’t shake hands with you..? Something the Japanese don’t do..? I’m really just not sure how you arrived at your perception because it’s easy enough to get people wrong even in the West. If it takes a while for assholes to reveal themselves, it might take even longer in Japan where people usually hide behind their rank. But you were somehow able to sense insult or negligence right off the bat in a foreign culture where the etiquette is very different. I also wonder whether you’ve considered how direct eye contact in Japan is eschewed, especially toward an elder. Although I’m half-Japanese, I still get caught out on this one, because in our Western culture direct eye contact is a mark of equality and respect, even friendliness. Whereas in Japan, it can come across as intimidating. I’ve got a bunch of similar tales to tell of cultural misunderstandings on the mat but I don’t want to take up too much of your time. I’ve been reading Gregory Bateson recently and I am using his concepts to help explain why we misunderstand the Japanese and vice versa. Often, these misunderstandings, or misperceptions if you like, take the form of a typing error, a category mistake. Like we think we are individuals whereas most Japanese self-identify as members of a group. As such, if I think somebody Japanese is being rude to me, it may not be because that person is rude but because some point of cultural etiquette has been breached. In other words, his collective sense of self was alarmed by unusual forms of address, in this case a) a younger woman actually hitting an older man on the head (an unlikely event in Japan), b) a foreigner not being sufficiently deferential or polite in the interaction (also involving sensitivity to context…after all, you were the visitor…whereas he may have likely been local…we don’t usually start behaving badly by attacking people whose table we join at the restaurant, even in the name of equality…after all, they were there first. In Japan, priority matters. We are supposed to bow to the Sensei for example and to Sempai both of which are Confucian concepts by the way. “Sensei” literally means “gone before” and ‘senpai’ means more experienced. In other words, it would be a contradiction to want to be part of this hierarchical system while condemning its building blocks. Holy cow,.! I mean, even if you knew the guy, it would be like Olive hitting Popeye, you know..! Please don’t get me wrong, I am not advocating anything for the moment, other than a greater understanding between the two cultures. There are assholes in both cultures but there are also misunderstandings that can get blown out of proportion. I think we are only just beginning to tease out what these differences actually are. I see my role as doing just that, making people see where we connect and where we don’t and thereby to put a hold on our quick judgments until we can see clearly (a useful skill, I think, like mindfulness, non-judgmental awareness). I think, for example, that the ranking system has been taken to mean something medieval and primarily technical. I don’t think this is correct but this is what it has become in the West, mainly because of the high value we place on technology, and thus technical achievements of all kinds. I mean, we see through cultural lenses and see only what our culture allows us to see and this applies to how we rank good and bad behavior, the meaning of knowledge, how we learn, how we teach, how we organize, how we speak, how we listen, the role of emotional communication or the lack thereof, differences in notions of self-control, in autonomy vs following group norms and even self-development, differences in the meaning of creativity. In short, I see what precious few see whether they are Japanese or Western because each side tends to assume that the assumptions of their culture apply universally. I mean, it would be a joke if they weren’t serious..! I’ve begun to write about these kinds of things in a semi-autobiographical mode. I think you might find it useful, funny, and hopefully enlightening.

Thank you for your insight.

Congratulations on being the first female member!! I have only trained in Aikido in Japan (20 years) and I’m a Canadian female. There is a tendency to try to keep the ‘spirit’ of Japan mystical and hidden. In fact, besides the fundamental cultural rules that anyone can find in a book, the Japanese culture is as unique as any other. There exists racism, misogyny, power harassment as well as cooperation, compassion and fairness. Since Aikido does not have competitions (for the most part), egocentric, power hungry teachers can, and often do, run dojos for their own benefit only. My experience here in Hokkaido has been very positive and recently, with the aging sensei population, my position will/may advance. I will begin a daytime class to encourage a more diverse membership and I also teach Aikido in English in elementary schools. The important thing that I want to teach others about Aikido is that reciprocity is at the heart of good Aikido, just as it is in life. There is no dominance, submission or winning and losing. We are reciprocal partners who mutually benefit each other. Perhaps that understanding is why women are attracted to Aikido and how it fundamentally differs from other martial arts.

Thank you. Congratulations to you! I agree.

This is a very inspiring interview to me. Penny Bernath Sensei exhibits true wisdom and grace under pressure, in my opinion. Both her actions and her telling of the stories show straightforward honesty and resolve.

The story that ends up with her taking ukemi in summer camp for Doshu is amazing!

Congratulations for your appointment to the technical committee. I am grateful you accepted. I hope Aikido Journal will check in with you again.

And if an interviewer is like an uke, then Nice Ukemi!

Thank you.