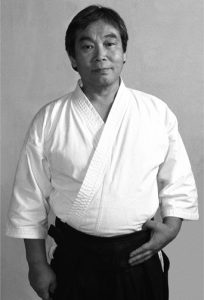

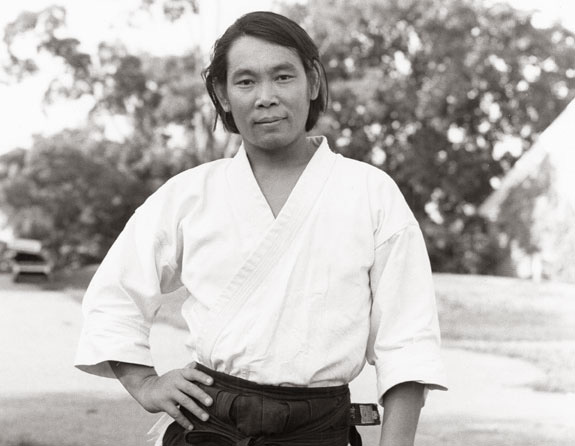

This is an excerpt of an interview with Mitsunari Kanai Sensei, conducted by Stanley Pranin, which took place on August 22, 1979, at the New England Summer Camp. This interview will be included in our upcoming Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, limited edition book. You can preorder a copy here until December 30, 2022.

I think it is significant that from your point of view, Sensei, the techniques of Aiki Ken (sword) are actually those of taijutsu (body techniques). On the other hand, some famous teachers say that if we don’t do jo and bokken training then we aren’t doing real Aikido. Even so, there are very few dojos where such training in these weapons can take place. What is the solution to this problem in your opinion?

If it is true that the sword work of Aikido is performed on the basis of the principles of body arts, then I think people who train only in taijutsu should be able to pick up a bokken or jo and use it. Certainly, nowadays, jo and bokken classes are very limited. It’s a matter of space. You need an appropriate area to train in and so, generally, the practice of Aikido has centered on taijutsu.

I have been studying the life of O-Sensei and the history of Aikido. As a result, some of the points that had previously given me trouble have slowly cleared up. Don’t you think that most of the present teachers actually received only a little direct teaching from O-Sensei? The reason for this being that for 15 years after the war he lived in Iwama and visited other dojos for only very short periods of time. I wonder if a proportion of the teachers didn’t have very much opportunity to learn the sword and stick.

I suppose that one could say that but in my own case, when I entered as an uchideshi (circa 1958), O-Sensei divided his time equally between Iwama and the Hombu Dojo. For that reason, I don’t think that anyone can say that Hombu people didn’t learn much directly from O-Sensei. It’s simply a matter of each person taking from within O-Sensei’s technique that which he could grasp and the resulting differences are another problem. Isn’t it unfortunate that the number of such people is so small? I’m sure that those who have grasped it really have something, but of course, different people have a different image of the Founder and I don’t think that anyone can say that that man’s image is wrong and this person’s idea is mistaken.

“I think that the beauty of Budo comes from an effective and really efficient and rational control of the partner or adversary.”

O-Sensei’s life in Budo went through various stages. There were the Hokkaido and the Ayabe periods, the time in Tokyo, Iwama during the war, and his later life in Tokyo. Each period found O-Sensei’s technique different from the last. According to Saito Sensei, during the post-war period, O-Sensei gradually systematized his technique. Then, in his later life his technique became more abstract. There were more explanations in terms of the Kamisama (gods) and he very rarely talked of technical matters. From your own experience, what sort of things did his teaching consist of? Were they general matters or did he speak of details?

Well, they were not what you would call technical matters. He would throw the uchideshi, (live-in disciples), with very little in the way of explanation and we would grasp what we could of the feeling of the technique while we were flying through the air. We were Budo people, so I think that’s the way it should be. Without trying to keep everything very rigid in our minds, like “1 plus 1 is 2”, we learned and progressed on our own by being thrown by the master and feeling his technique. Then we’d throw our partner with that same feeling. That’s how it should be, I think.

We have movies and photographs of O-Sensei mainly from the latter part of his life. The image of O-Sensei held by most people today is of a very kind, little old man. Few have the image of a vigorous, powerful Budoka in his fifties. For us it is very difficult to understand abstract explanations about the gods and Shinto religion, but I think that if we could look at O-Sensei’s explanations from before that period it might become easier to understand, to grasp, what it was he was saying later in his life. Do you think it is important to study the teachings of O-Sensei as a younger man, in his fifties or sixties?

Yes, it’s necessary, isn’t it? Certainly the techniques of O-Sensei later in his life look extremely soft, but if people see only the pliability and seek after that alone, then I think we can say that Aikido ends up looking like some kind of dance. But, if a person who can really see looks, I think that he will realize that behind even the smallest movement, O-Sensei had the power that comes from training in real Budo. Although I admit that if you try in every way to make a technique soft and flexible and concentrate solely on moving so as not to collide with your partner, you can create something like a wonderful dance. This is not Budo. Perhaps it is going against the times, but even so, if you really dig back into any technique, really find out how it is constructed, how it can vary, to what extent it can change, then from that basis I think that you can say to what extent it can be extended in the future. At any rate, if Aikido is Budo, then as such, when we talk about “shikaku”, when we can enter the “blind spot”, or when we are perfect in terms of technique, then I think it is necessary to display over and above these things, the softness and beauty of harmoniously encountering your partner. I think that the beauty of Budo comes from an effective and really efficient and rational control of the partner or adversary.

“At first I couldn’t take ukemi very well. I had done Judo and so I had enough confidence in Judo ukemi, but when someone like Tamura Senpai (Nobuyoshi Tamura of Marseille, France) got a hold of me I always bumped my head on the mats, and there didn’t seem to be anything I could do about it.”

We have heard a very interesting story about your first encounter with O-Sensei from a mutual friend Mr. Katusaki Terasawa, but I think we’d all be interested in hearing it from you directly…

Please forgive me, but I really don’t want to talk very much about myself. If you want to know, Mr. Chiba and Mr. Kurita are the men to see, so please ask them when you have a chance.

Presently most information about Aikido is collected by the Hombu and sent out from the Foundation to the various Japanese Shihan around the world and finally distributed to the Aikidoka in the various nations. Things are done from the top to the bottom. I suppose that this is necessary, but in 30 or 40 years from now, we may see some excellent Aikidoka develop in overseas dojos. In my case, I try, through the pages of this paper, to be a vehicle of communication by circulating interviews with famous Japanese sensei residing in foreign countries, and conversely, passing on the views of overseas practitononers to those in Japan. I understand your reluctance to talk about yourself here. What I wanted to say is that people just starting Aikido find so many things that they don’t understand that they are often completely without confidence. I think that if they could know a little about your “roots”, it might be a great help to them. For example, did you have trouble with ukemi when you first started? Was there a time when the techniques were difficult for you?

Well, yes. At first I couldn’t take ukemi very well. I had done Judo and so I had enough confidence in Judo ukemi, but when someone like Tamura Senpai (Nobuyoshi Tamura of Marseille, France) got a hold of me I always bumped my head on the mats, and there didn’t seem to be anything I could do about it. Judo ukemi in a certain respect didn’t seem to be of much help. And also, because I tried to understand Aikido in terms of Judo, I wasted a lot of time before I began to do anything that could be called real Aikido. Everything I did, every move, was from a Judo point of view, and this was something that I couldn’t get away from for a long time.

Sensei, why did you start doing Judo and why did you give it up and start training in Aikido?

I felt that something was missing, something lacking. I like Judo very much, even now. To flip someone up and over for a throw is a feeling that I can never forget. But Aikido has something even above that, something better. It is more difficult and much more interesting. It’s more interesting, but a little too difficult. I don’t think there is another Budo in the world that is this rational. If a person should be taken up by this kind of art and start training or after starting should come to understand how wonderful it is to the degree that he can never give it up, then I think that such a person displays a clarity of mind that is truly wonderful to see. A person who can really see through practice, and who puts his whole self into training, regardless of where he comes from, is a wonderful thing to see. The only problem is that the more you do this kind of training, the more difficult it becomes! That’s the feeling I get.

I understand that you saw O-Sensei’s Aikido on television. Would you tell us what your impression of it was at that time?

Mr. Tamura was taking ukemi. They began with sword work. At first I didn’t know that what they were doing was Aikido, but anyway I thought that it was rather strange. After I saw O-Sensei doing taijutsu, people on a lawn, and I to myself, “Is he really throwing them?”, “ Are those techniques Anyway, looking at that they were that, throwing thought throwing really effective?” the ukemi I could see different from our Judo ukemi. Though the ukemi seemed light as a butterfly, they seemed to do the job. Although I didn’t understand them myself, there was a period when I researched them on my own because I felt that they must be the real thing. This was during Judo practice. I’d go over to one corner of the dojo and try the ukemi. When I did, my teacher would come over and correct me back to Judo style.

At that time weren’t there rather few uchideshi at the Hombu Dojo?

At that time there was Mr. Tamura, and following after him, Mr. Nishiuchi. When I entered, Mr. Yamada was there. Then Mr. Chiba, Mr. Kanno, and me, and then Mr. Kurita entered a little after.

“I dislike any instructor who lets his nationalism come to the surface. The nationality of a person makes no difference. That is the very reason that Aikido was sent out to the world, for all people to do the same Aikido, for them to do World Aikido.”

Were you allowed to start training right from the beginning? We recently interviewed Yonekawa Sensei and during that discussion he told us that before the war, the deshi started by cleaning the dojo and doing other odd jobs and were not able to train in Budo at all.

We were in the same situation. Fieldwork, splitting firewood, hauling water, laundry, and preparing the bath… In the first place, these were jobs that I thought no one ever did any more and, in addition, there was nothing to eat!

Sensei, you’ve been doing Aikido for over 20 years now, haven’t you?

That’s right.

Recently a certain person was explaining your kotegaeshi and I noticed that it was very different from what I remembered your technique as being. I wonder if you would mind talking about your own evolution in Aikido, about changes in technique and in your way of thinking?

Recently a certain person was explaining your kotegaeshi and I noticed that it was very different from what I remembered your technique as being. I wonder if you would mind talking about your own evolution in Aikido, about changes in technique and in your way of thinking?

It’s difficult for me to say myself how my technique has changed. It’s just a matter of spending a period on a particular technique and trying to delve a little more deeply into them one at a time. I feel sure that if I think about where on earth a particular movement came from, on my own, then I will be able to recreate once more something exactly the same as O-Sensei did at some stage in the past. Don’t you think that if any person spends a certain period trying to research some particular thing that he too must eventually have that same technique result? Anyway, this isn’t how a person’s technique evolves; it’s only a matter of how a person who is learning something sees things in relation to the level of his own research. I can’t say how I will change in the future.

You’ve lived in the USA for 12 or 13 years, I believe.

That’s right. 13 years.

As everyone knows, Aikido began in Japan. And you, Sensei, have lived in the USA for 13 years. Certain people hold the view that only a Japanese person can do “real” Aikido…

That is absolutely not the case. There is no reason whatever for thinking such a foolish thing. It’s just certain people who think like that. There are also those who think that Aikido in America from now on will be taught according to the American way of thinking. I don’t think that such a thing is Aikido. It makes little difference if a person is an American. The point is that it is not “American Aikido.” If they are doing “World Aikido,” then it’s all right. Anyway, I dislike any instructor who lets his nationalism come to the surface. The nationality of a person makes no difference. That is the very reason that Aikido was sent out to the world, for all people to do the same Aikido, for them to do World Aikido.

Those people use the language barrier as their first reason for their views. They say that foreigners can’t communicate directly with their sensei. And then they point out that non-Japanese have only a shallow understanding of Japanese culture and can never understand the “Yamato Seishin”, the Japanese spirit or mind.

That doesn’t matter. Aikido isn’t a matter of words. It’s one of the Kokoro, the mind or spirit. It is nothing but the confrontation of two feelings, two frames of mind, from out of which each partner tries to grasp something. Don’t you agree? The confrontation of two human beings. Grasping that feeling is Budo. It is Aikido. If you leave out this element, then I think this thing we call Aikido is impossible.

I’m sure that we can all learn much from your talk, Sensei, and we thank you very much for giving us your time for this interview.

Thanks for sharing this article. I love Sensei Kanais view on Aikido, his humbleness, his explicit rejection of nationalism and his view on Aikido as a martial art. Wonderful interview also by Mr. Pranin. So sad that both had to die too early.

Regards, Jochen