Born 1947 in Yamagata Prefecture. Entered Kokushikan University in 1966. Met Kenji Tomiki there. After graduation, he devoted himself to aikido training under Tomiki and Hirokazu Kobayashi. Now teaches in the budo section of the physical education department at Kokushikan University, the Physical Education Department at Waseda University, and at the Osaka Police Academy. Director and instructor within the Japan Aikido Association and full-time instructor at the Shodokan, the JAA’s central dojo.

Japan Aikido Association and Shodokan

The Japan Aikido Association (JAA) was formed in March 1975 by aikido club alumni from Waseda, Kokushikan, Seijo, other universities, as well members of various private aikido clubs, as a general administrative organization dedicated to the aikido ideals and the competitive aikido created by Kenji Tomiki. Two of the most important participants in the history and development of competitive aikido were the Waseda University Aikido Club and the Shodokan. The Waseda University Aikido Club was founded by Kenji Tomiki in the spring of 1958 as an experimental locus for his competitive aikido development, and it eventually came to play a leading role in the promotion of competitive aikido both in Japan and abroad. The Shodokan was established by Tomiki in April 1967 as a dojo dedicated to his aikido research. Tetsuro Nariyama was sent to the Shodokan to serve as its new instructor in March 1970, and in 1976 it was re-dedicated in a new building with a 70-mat dojo.

At the Shodokan dojo (which serves as the Japan Aikido Association’s Kansai regional headquarters) in Osaka, Aikido Journal spoke with Shodokan director and chief instructor Tetsuro Nariyama about “competitive aikido” and its training methodologies. Nariyama Shihan also shared some of his experiences training under Kenji Tomiki and spoke about his hopes and aspirations for the future of competitive aikido.

Interview by Stanley Pranin, February 27, 2001

Under the strict gaze of Tomiki Sensei

AJ: Watching your practice today, I see that a kind of vigorous free sparring (randori) involving precise distancing and timing is a significant part of your aikido training here. I think there may be many aspects of this kind of practice that other aikido dojo that don’t normally use such matches (shiai) might find very useful. Sensei, you are currently the Shodokan’s chief instructor. Can you tell us how you first got involved in aikido?

Nariyama: I practiced judo in high school and was a great admirer of many of the Olympic judo players back then. One of my high school teachers was an alumnus of Kokushikan University, and through his introduction I was able to enroll there myself. I had intended to join the university judo club, but one of the senior students there told me “we only train heavyweights here” (laughter), so I gave up that idea. As it happened, another of my seniors, this time one from my dorm, invited me to have a look at an aikido practice. I say “invited me to have a look,” but that’s actually putting it nicely. In fact, once I got in there they literally closed the door behind me and wouldn’t let me leave until I agreed to join! (laughter)

Tomiki Sensei, whenever he came there to teach, always left an intense impression on me. He was one of those teachers who didn’t talk that much. He just watched, with his eyes narrowed, scrutinizing everything. All of the senior students were always on pins and needles when he was there, and there was a kind of electrified feeling in the air. I felt he was an impressive and amazing teacher.

I joined the aikido club figuring I could always just quit whenever I wanted to if I didn’t really like it. But as it turned out, a little later Hideo Oba* Sensei came to teach, and quitting would have been very awkward since he also happened to be my physical education lecturer. So I stayed on, and eventually, from my sophomore year, I even became Oba Sensei’s teaching assistant. I learned a great deal from him over the next three years. He had a great sense of humor, and was the kind of teacher that really grabbed his students’ hearts. Normally a university professor in his position needed only one teaching assistant, but in Oba Sensei’s case the students were practically lining up for the privilege! (laughter) I assisted him in many of his other classes as well.

*Hideo Oba, 1911-1986, second director of the Japan Aikido Association

Tomiki’s enthusiastic lectures resonate strongly with students

AJ: Did the Kokushikan University aikido club have any interaction with the aikido club at Waseda University?

Yes, even starting in my first year we used to go there to train with them. Sometimes Oba Sensei would be teaching, or Tomiki Sensei would be there giving talks. I also participated in most of the Waseda training camps (gasshuku). Both Tomiki Sensei and Oba Sensei came to those, as did most of the senior students responsible for teaching, so it was always invaluable training.

Tomiki Sensei often spoke about his dreams for the future, namely about spreading the competitive aikido he had created around the world. I think he even hoped it would someday be introduced to the Olympics. He said that it would first have to be practiced nationwide in Japan, and then move into international competitions, but eventually, he felt, it would be worthy of becoming an Olympic event. Such extremely passionate ideas undoubtedly had a lot of resonance among us students, to the extent that many of the people who listened to his talks back then were motivated enough to continue and in fact are still with us, many working in important roles among the JAA executive staff.

On the other hand, sometimes Tomiki Sensei’s lectures could be very difficult to follow. Often at the training camps you’d see a lot of us students sleeping through them at the back of the room! (laughter). Still, what he was saying somehow seemed to find its way into our heads—maybe like one of those “learn while you sleep” programs… (laughter).

Did you ever train directly with Tomiki Sensei?

In most of the universities, it was very common for Tomiki Sensei to use the aikido club leaders or captains, most of them fourth-year students, as his uke. I eventually became the captain of the Kokushikan aikido club, and in that connection performed as Tomiki Sensei’s uke at events such as the meeting of the committee preparing for the establishment of the Nihon Budo Gakkai.

I moved to Osaka in March 1970, and from then until a few months before his death in December 1979, Tomiki Sensei used to visit the Shodokan on a regular basis. Whenever he came we would get together groups of students from the Kansai region to hold seminars, and he also taught general classes at the Shodokan.

Tomiki Sensei, whenever he came there to teach, always left an intense impression on me. He was one of those teachers who didn’t talk that much. He just watched, with his eyes narrowed, scrutinizing everything. All of the senior students were always on pins and needles when he was there, and there was a kind of electrified feeling in the air. I felt he was an impressive and amazing teacher.

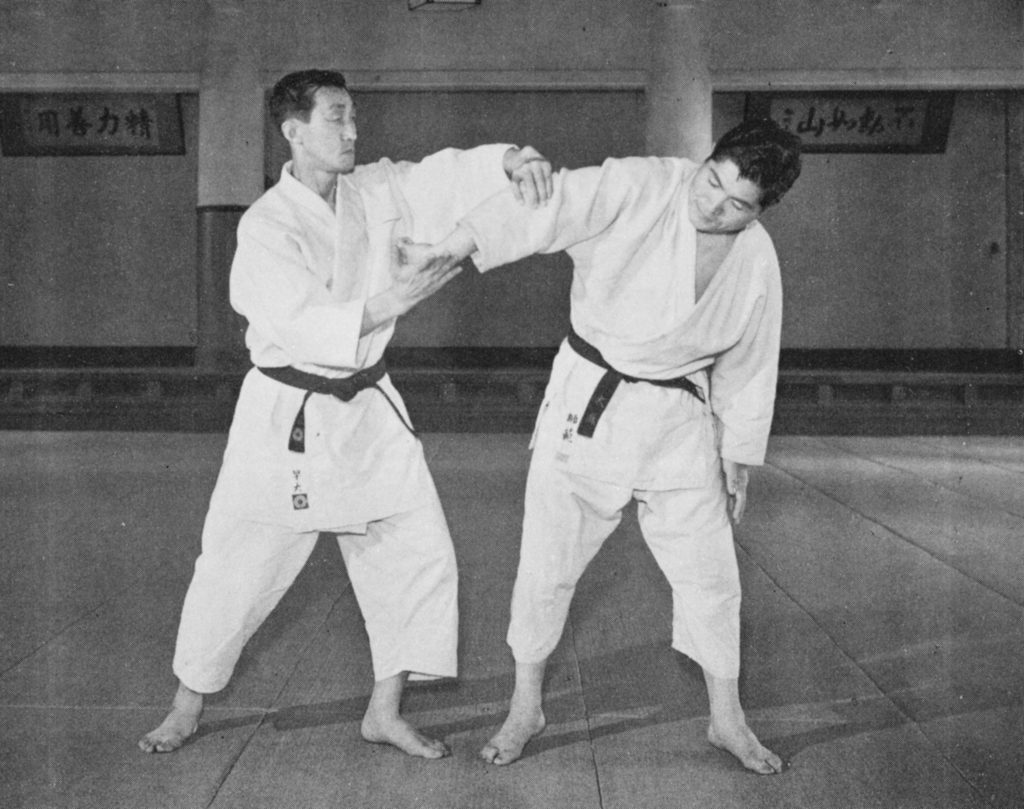

Tomiki Sensei had a powerful wakigatame (armpit lock), one you couldn’t escape from even if he was using just one hand. Our joint techniques are designed to prevent the opponent from escaping, but also to not be overly painful. We have to train to have that kind of control. The key is to have good body movement combined with an ability to blend with the opponent. Tomiki Sensei was extremely skilled at these things. These days I don’t think we can say such skills are as alive and well as they might be in our ideal randori, and improving this is something we have to ask of the young people practicing today.

Spreading competitive aikido in Osaka

I’ve heard that Tomiki Sensei hoped to make the Shodokan, as the central dojo of the Japan Aikido Association, a focal point of activity for competitive aikido…

The Shodokan taking that central role actually had to do with meetings and relationships among a many different people. There was, for example, Toshio Nishimura, who first introduced Tomiki Sensei to current Shodokan director and JAA vice-chairman Masaharu Uchiyama. Nishimura was a childhood friend of Hidetaro Nishimura (no relation), the man who brought Tomiki Sensei into aikido in the first place. Uchiyama was not in particularly good health, so Toshio Nishimura suggested he take up aikido, saying he knew an excellent teacher, and introduced him to Tomiki Sensei around 1963. Uchiyama’s health did gradually improve, and later he expressed interest in having a full-time aikido teacher, so Tomiki Sensei introduced him to one of my seniors, who started going to the Shodokan as a full-time instructor.

And sometime thereafter Tomiki Sensei sent you to work on the development of competitive aikido in the Kansai region?

Actually, there was one other teacher sent before me, but he eventually became too busy with his other work and I was nominated to take over for him. I think Tomiki Sensei was definitely interested in training people who would become full-time teachers.

There happened to be some students in Kansai who said they wanted to see aikido, so about twenty people from Waseda, Seijo, and Kokushikan went down to give a demonstration. The students who attended soon indicated their interest in starting aikido, too, and sent a request for an instructor via the late Hirokazu Kobayashi*, who relayed the request to Tomiki Sensei. That instructor turned out to be me.

*Hirokazu Kobayashi, 1929-1998. Aikikai 8th dan. Operated the Osaka Buikukai dojo in Osaka. Frequently taught in France and Italy.

Learning the techniques of Ueshiba Sensei from Hirokazu Kobayashi

How did Kobayashi Sensei and Tomiki Sensei know each other?

They were introduced by the late Tadashi Abe,* who was a graduate of Waseda University and so knew Tomiki Sensei fairly well. Abe also must have trained under Tomiki Sensei back when he was still teaching at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, and I think probably respected him as a valued senior. Abe and Kobayashi also had a close relationship given their similar roles as Aikikai shihan, and apparently they got along well on a personal level, too. So Abe Sensei was the connection who introduced Kobayashi Sensei to Tomiki Sensei.

Tomiki Sensei often spoke about his dreams for the future, namely about spreading the competitive aikido he had created around the world. I think he even hoped it would someday be introduced to the Olympics. He said that it would first have to be practiced nationwide in Japan, and then move into international competitions, but eventually, he felt, it would be worthy of becoming an Olympic event. Such extremely passionate ideas undoubtedly had a lot of resonance among us students, to the extent that many of the people who listened to his talks back then were motivated enough to continue and in fact are still with us, many working in important roles among the JAA executive staff.

*Tadashi Abe, 1927-1984. Entered Iwama dojo as an uchideshi during WWII. Relocated to France in 1952 and stayed for several years as a pioneer of aikido there

Also, Kobayashi Sensei was usually Ueshiba Sensei’s uke whenever he visited Kansai, so the two of them also had a close relationship.

Kobayashi Sensei actually seems to have had a specific reason for going to see Tomiki Sensei in the first place. In one sense, Tomiki Sensei could still be considered Ueshiba O-Sensei’s student, so I think there may have been an element of “What do you think you’re doing, going off on your own like you are?!”, a sort of a complaint against Tomiki Sensei, at least at first. (laughter)

Tomiki Sensei dealt with Kobayashi Sensei’s complaints in a very reasonable, gentlemanly fashion, never getting angry and answering each question very logically and clearly. He then went on to talk about his dreams for aikido, and Kobayashi Sensei was apparently impressed. The demonstration of Tomiki Sensei’s way of doing things to the students in Osaka came together soon after that. So as you can see, numerous other people had already been involved in various ways by the time I was sent to Kansai.

My initial impression was that I was being sent to Osaka to teach. But just before I left, Tomiki Sensei said to me, “Nariyama, when you go to Kobayashi’s place I don’t want you to just be teaching; I also want you to learn from Kobayashi the things I learned from Ueshiba Sensei.” So, with that in mind, I came here to teach and learn at the same time.

What were Kobayashi Sensei’s techniques like?

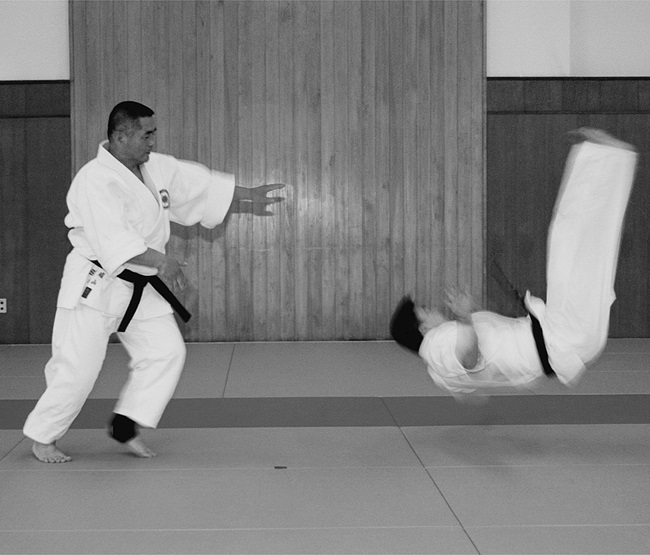

Very sharp and intense. Even when he did throwing techniques like iriminage, I felt like I was being pounded into the mat. And his joint locks were like none I’d ever felt! (laughter) The joint techniques I learned from Tomiki Sensei and Oba Sensei were more about controlling the joint, whereas Kobayashi Sensei’s focused more on having an extremely intense effect. He was also very good at explaining things logically. I spent about six years training like an uchideshi under Kobayashi Sensei, while on the other hand also teaching Tomiki Sensei’s randori training method at the various universities around the region.

Kobayashi Sensei eventually started asking me to assist him at some of his other various dojo. I remember riding next to him in his Volvo as we went around to the different dojo, listening to all the interesting things he had to say. Most of it had to do with Ueshiba Sensei, who he seemed to think about a great deal. He himself had been very strong in judo, probably a fourth or fifth dan, and before that he’d also practiced swordsmanship. He has a lot to say, for example making comparisons with Ueshiba Sensei’s sword technique and so on. As I spent more and more time with him, he also taught me a lot of what you might call “tricks and techniques of the trade,” including many things that have since been a great help to me. And the techniques he taught me were themselves a real treasure chest.

Our joint techniques are designed to prevent the opponent from escaping, but also to not be overly painful. We have to train to have that kind of control. The key is to have good body movement combined with an ability to blend with the opponent. Tomiki Sensei was extremely skilled at these things.

Do you think Kobayashi Sensei ever came to accept Tomiki Sensei’s competitive aikido theories?

I think he did, although he also probably felt there was something of a gap between the stated goals, as he understood them to be, and the realities of training. He often said that we needed to work a lot more on bringing more “aikido-like” techniques in our competitive matches. Tomiki Sensei seems to have felt the same way. He gave us a lot of “homework” involving testing his ideas to make our match training more aikido-like. Many of the practice methods we use today came out of those studies.

Hideo Oba Sensei

Earlier you mentioned Hideo Oba Sensei. Please tell us a bit more about him.

Oba Sensei started out doing a lot of sword training, and then when he was in Manchuria he also practiced naginata, iai and various other arts. If you added up all his ranks, he’d be a “several-dozen-dan.” Tomiki Sensei also told me that Oba had trained under Jun’ichi Haga* in Manchuria. In fact, Haga Sensei apparently even once asked Tomiki Sensei if he “could have Oba Sensei as his own student,” so I imagine that in addition to his aikido, Oba Sensei must have been quite a swordsman.

*Jun’ichi Haga, a well-known iaido and kendo expert, a top disciple of swordsman Hakudo Nakayama and a friend of Morihei Ueshiba

Tomiki Sensei told me that back in Kobukan dojo days, he and Ueshiba Sensei used to train in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu under Kosaburo Gejo.* I believe that Gejo Sensei and [Sokaku] Takeda were also very well acquainted, so there is even a link to Takeda Sensei.

*Kosaburo Gejo, an Imperial Navy Admiral and expert in Yagyu Shinkage-ryu sword, studied under Morihei Ueshiba from 1925 through the early 1930s

Another person to mention is one of Ueshiba Sensei’s prewar students named Tesshin Hoshi. Tomiki Sensei used to say, “If Hoshi had lived a little longer, my aikido probably would have turned out a little different.” Hoshi trusted Tomiki Sensei very much, and I think Tomiki Sensei appreciated Hoshi a great deal, too, particularly on a technical level.

Adding competition to aikido based on the theories of Jigoro Kano

Tomiki Sensei seems to have used the Waseda dojo as an kind of laboratory for the gradual development of competitive aikido…

He did, yes. But before the Waseda Athletic Department agreed to make aikido part of their regular physical education program, they told him that “anything whose skills can’t be measured objectively isn’t considered suitable to become an official course.” To which he immediately replied, “I can do that” and guaranteed that he would make it possible to measure aikido skill in a safe way. With that the university permitted the establishment of an aikido club. At that time at Waseda, for something to be recognized as a club, it had to be associated with a lecture course. So from the time aikido was recognized as an official club in 1958, Tomiki Sensei was teaching it as a lecture course. Up until then he had to teach it as “judo exercises” (judo taiso), even though what he was doing was aikido.

Tomiki Sensei dealt with Kobayashi Sensei’s complaints in a very reasonable, gentlemanly fashion, never getting angry and answering each question very logically and clearly. He then went on to talk about his dreams for aikido, and Kobayashi Sensei was apparently impressed. The demonstration of Tomiki Sensei’s way of doing things to the students in Osaka came together soon after that. So as you can see, numerous other people had already been involved in various ways by the time I was sent to Kansai.

Tomiki Sensei’s research into competitive aikido actually went further back than his association with Waseda. Before heading off to Manchuria, he went to visit Jigoro Kano Sensei. Kano said to him, “Tomiki, the kinds of things you’re doing at Ueshiba’s place will be needed from now on, but the problem is finding ways to have people do them.” To which Tomiki Sensei says he boldly replied, “With your theories, Sensei, I don’t think it will be impossible at all.” That conversation may have marked the real start of his research into competitive aikido. With the integration of judo theory, he felt, there was no reason match training couldn’t be introduced to aikido. I think he felt that unless he finished the parts that Kano Sensei had left [undone], the whole of jujutsu would not ever be completely modernized. Kano Sensei, in his development of jujutsu into a competitive sport, did not modernize the whole of jujutsu; some things he simply removed, including quite a few joint-locking and striking techniques, and I think Tomiki Sensei felt that by working these back into a competitive format based on Kano Sensei’s ideas, he could help complete the modernization of jujutsu. Kano Sensei’s comments, too, suggest that he himself viewed judo in that broader sense.

What Tomiki Sensei was doing was based on his solid understanding of what he’d learned from Ueshiba Sensei. I don’t know how Ueshiba Sensei himself felt about it, but many of the others around at the time didn’t approve. At the Kodokan, Tomiki Sensei was looked at as “that individual who went over from judo to aikido,” and when he went to aikido he was thought of as “Tomiki who does judo.” (laughter) He felt pressure from both sides, and he told me it sometimes felt like everyone was against him.

There was a time when Tomiki Sensei actually called what he was doing “Dai Ni Judo” (lit. “the Second Judo”), in the sense that he was developing striking and joint techniques into competitive forms, and in that way was modernizing the older jujutsu.

Did the name “Dai ni Judo” come before the name “shin aikido” (“new aikido”)?

Yes, I think so. At one time, he seems to have thought about linking what he was doing to judo, but in the end he was particular in preferring the name “aikido.” I think the Aikikai probably spoke with him on numerous occasions about using some other name like “Tomiki-ryu” or “Tomiki System.” But he always insisted that his efforts to develop a competitive system were not intended to create a separate style or faction, and he never gave ground in his thinking on that.

There were also some who questioned the validity of him issuing dan rankings on his own authority. But to these he replied, “Fine, please handle all dan rankings for me in the future.” But he also asked that the ranks he’d already given to current practitioners be recognized. He wanted at least some part of what he was doing to be recognized. I heard that Kisshomaru was very happy with that, and for a time there was a kind of “thawing” in relations.

I think he did, although he also probably felt there was something of a gap between the stated goals, as he understood them to be, and the realities of training. He often said that we needed to work a lot more on bringing more “aikido-like” techniques in our competitive matches. Tomiki Sensei seems to have felt the same way. He gave us a lot of “homework” involving testing his ideas to make our match training more aikido-like. Many of the practice methods we use today came out of those studies.

I don’t think this is widely known, but in November 1972 there was a demonstration in which several of the different aikido groups participated together, including the Japan Aikido Association (Tomiki Sensei), the Yoshinkan (Shioda Sensei), and the Aikikai (Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba). It was at the Second Japanese Budo Festival (Nippon Budosai), an event organized at the initiative of Ryoichi Sasagawa*. Mr. Sasagawa set one condition, however. He told Kisshomaru Sensei, “There seem to be several different aikidos, but I’m not going to put aikido in the demonstration unless they all participate together.” Kisshomaru Sensei agreed, as did Tomiki Sensei and Shioda Sensei, and so the demonstration was held. The time allotted to Shioda Sensei and Tomiki Sensei may have been slightly less than that given to the Aikikai, of course.

*Ryoichi Sasagawa, a philanthropist known for his support of the martial arts

From empty-handed to knife randori

Do you know who wrote the technical explanations for the first edition of Ueshiba Sensei’s Budo Renshu (Budo Training), the one with hand-drawn illustrations by Takako Kunigoshi? I believe it was Tomiki Sensei who edited it?

Right, exactly. His business card is reproduced in the copy book I have. It reads “Kenji Tomiki — Standing Secretary (jonin kanji), Kobukan.” There are also places where his handwriting appears. I’ve saved dozens of letters that Tomiki Sensei wrote to me over the years, and the handwriting closely resembles that in the handwritten explanations in Budo Renshu. That was a time when he was still practicing nothing but katageiko (training through set forms), and I think it was only after the war that his thinking turned to the way we know it today. The essays and such he wrote before the war were completely different.

In what ways specifically did Tomiki Sensei’s thinking change?

Well, it seems that the kind of deep training he was doing, based on his study of Kano Sensei’s theories, gradually led him through a process of inductive verification and testing.

I’m grateful that I had the opportunity to be with Tomiki Sensei so continuously for 13 years, starting from my university days. There are many people quite senior to me and my generation, but many of these may not have quite realized how his thinking gradually changed. Whenever he changed something he’d been doing to something else, it was always based on some principle and he always had a specific reason. One reason I’ve been able to continue until today is that I happened to be there to see and experience those changes. It would have difficult to explain the changes that were made without having seen them for myself.

What Tomiki Sensei was doing was based on his solid understanding of what he’d learned from Ueshiba Sensei. I don’t know how Ueshiba Sensei himself felt about it, but many of the others around at the time didn’t approve. At the Kodokan, Tomiki Sensei was looked at as “that individual who went over from judo to aikido,” and when he went to aikido he was thought of as “Tomiki who does judo.” (laughter) He felt pressure from both sides, and he told me it sometimes felt like everyone was against him.

Speaking of changes, what was the rationale behind changing the originally empty-handed randori to randori done using a [mock] knife (tanto)?

There was a very important reason for that, which had to do with distancing. In empty-handed randori, without the knife, the opponents inevitably close the distance into a very close-quarters situation. For that reason, judo players had a great advantage in the empty-handed contests. While techniques like ashibarai (foot/leg sweep) and uchimata (inner thigh reap) were not included among the regulation techniques, seionage (shoulder throw) was, and so those with judo experience would always go for seoinage and use that to win.

So the introduction of the knife (tanto) was to ensure a wider combative distancing?

Exactly, because aikido uses distancing and it doesn’t necessarily allow the legs and hips to reach. Training allowing the legs and hips to reach effectively would mean you probably wouldn’t be able to stand for more than a few seconds against a skilled judo man of, say, 4th dan. So the knife was introduced to ensure that the aikido training takes place at a more appropriate distance, relatively out of range of leg and hip techniques.

There were various teachers who offered Tomiki Sensei their advice. For example, he asked a number of judo teachers to take a look at the striking and joint-locking randori methods he’d developed. They pointed out numerous weaknesses and flaws with comments like, “Right there you’d be open for a hanegoshi (hip spring) or taiotoshi (body drop)” and “There’s a chance to beat you with ashibarai (foot/leg sweep)” and so on. It was through these constructive criticisms that Tomiki Sensei suddenly hit upon the idea of introducing the knife into his randori, figuring that with a knife involved, most of the complaints voiced by the judo teachers would no longer be a problem.

As I understand it, Tomiki Sensei’s ideal was to practice kata (set forms) over and over in order to refine technique, then move into practical application of those within randori…

Yes, he used to say “kata and randori, like the two wheels of a cart.” It’s impossible to go straight if either wheel is out of alignment, so you have to take care of both of them. I’d like to point out, though, that having competitive matches, while in a sense an ideal way to train, is not the objective; the real issue is whether or not you have the ability to do excellent randori, and through that randori to build real skill. Doing aikido just for the purpose of using it in matches is no good. Matches are a result, not an objective in and of themselves. The real goal is to be able to do excellent randori training.

Trial-and-error while taking hints from other competitive sports

One of the great things about Tomiki Sensei was that he looked not only at budo, but at sports as a whole, and integrated anything he found worthwhile into his aikido research. One of the counter techniques I showed you earlier today, for example, was developed from an insight he got from sumo wrestling. There was a wrestler named Tochiakagi who took his opponent Mienoumi down with a technique called sakatottari (a counter to the arm twist known tottari). Tochiakagi was known for his flexible and unorthodox approach sumo, and when Mienoumi tried to take him down with an arm twist, he simply let all the strength go out of that arm and slipped around to Mienoumi’s rear, making him fall. Tomiki Sensei saw that and the very same day had everyone start doing something similar in our training. Later he also said, “Why not start recognizing the use of striking as a form of counter-technique usable by the knife-wielding side during the match?” He was urging us to look the possibilities for such things on our own. A lot of “hints” like that eventually found their way to his efforts.

I think the Aikikai probably spoke with him on numerous occasions about using some other name like “Tomiki-ryu” or “Tomiki System.” But he always insisted that his efforts to develop a competitive system were not intended to create a separate style or faction, and he never gave ground in his thinking on that.

There was a time somewhat later on when a lot of the students seemed to be focusing merely on winning the pennant, and so started using a strategy of winning matches by using points for the knife only, instead of trying to apply any real techniques. In other words, they would just thrust to get points and spend the rest of the match simply avoiding doing or receiving any other techniques. In a lot of those matches neither opponent would actually get off an actual aikido technique. Some pointed out that with such an approach, you could hardly even tell what kind of a competition it was anymore. So, Tomiki Sensei stepped in with a solution.

In volleyball, which happened to be very popular at the time, your team can only earn points when it has the serve. Taking a hint from that, Tomiki Sensei introduced a similar rule to the effect that your chance to get points came only after you’d had your turn thrusting with the knife and then swapped roles with your opponent. In other words, this rule made it so that no matter how much you thrust with the knife, the only points earnable during that half of the match were those taken by your empty-handed opponent for techniques applied.

Tomiki Sensei decided this was to be a new rule, and since he was the teacher, it was introduced very quickly, starting from that year’s tournament. Enviably quickly, in fact; if I tried introducing a new rule just like that I’m sure it would take a lot longer! (laughter) First, I’d have to present it to the Budo Gakkai committee. Then, before using it in public tournaments, we’d have to test it out among the university students and general practitioners in Kansai and present the results to the board of directors, and only after they gave the OK could we put it into the official rules. That’s how everything is now. It’s very democratic, actually…

Changing rules

Do you think the level of competition has improved since the 1st International Tournament in 1989?

I think it clearly has. For one, the techniques being done in competition have become much cleaner, and you hardly see anyone getting their feet all tied up together like they used to. Sacrifice techniques aren’t used so much anymore, either. Sacrifices where you fall over and then apply your technique from there are not used in our competitive matches. Dropping onto both knees to do a technique is an infraction and the technique goes unrecognized. If one knee touches it may or may not be recognized as valid, depending on the case. For the side applying the technique, that is.

The out-of-bounds rules are also a lot more strict now, much like they are in kendo, and we’re also more strict about the level of skill used to apply techniques. It’s considered a lesser technique if you manage to get complete control over the opponent’s attack, but in doing put him out of bounds. Such techniques are usually scored only as a koka (“minorly effective”) or yuko (“had effect”). The rules and regulations for refereeing are gradually being revised to preserve what we consider proper training methods.

It was through these constructive criticisms that Tomiki Sensei suddenly hit upon the idea of introducing the knife into his randori, figuring that with a knife involved, most of the complaints voiced by the judo teachers would no longer be a problem.

It must be difficult to make changes to the rules since you then have to communicate those changes to the worldwide competitive aikido community.

Yes, that can be a real problem sometimes! The people coming from abroad to participate in the competitions certainly don’t come with the intention of losing! (laughter) Probably that’s because those who perform well in the tournament can then use winning in Japan as a way to attract students. There’s an extremely strong emphasis on winning, I feel. Even if you’re following the refereeing rules, there are many cases where people will say, “What?! I’ve never heard of that!” To my mind, that kind of over-emphasis on winning seems a little… well… I don’t find it a very good thing.

Probably there are cultural factors at work there, particularly among competitors from overseas. There’s a real love of competition and competitive events, to the extent that sometimes people are more interested in watching a big football game like the Super Bowl than they are in, say, political events! (laughter) With that in mind, to what extent do you think Tomiki Sensei’s theories and ideals are understood among competitors from abroad?

Hmm, it’s hard to say; but my sense is that becoming personally skilled and strong tends to come before theories and ideals for many people. I’d be very grateful if people started giving more thought to the theories and ideals underlying Tomiki Sensei’s competitive aikido. Getting to that point may take some time, though, and may be difficult without more communication and more kinds of opportunities for contact.

I do think in most cases people are thinking mostly about themselves, and about their own skills improvement. This is probably true among Japanese competitors, too, of course. People may feel they won’t be able to continue their practice over there unless they personally become very highly skilled. Those coming to train in Japan tend to be very focused, because of the relatively limited amount of time they have. They usually return home much different than when they came. Their colleagues back home pick up on that and are in turn encouraged to come. That’s the kind of pattern I see now, and I think it would be good if this could become more widespread.

Toward development worldwide

What tends to happen among those top competitors who’ve won successfully during their peak, but then put on a few more years and can no longer work at such a high level? Do they continue on, satisfied with whatever level of randori they can still do, or do a lot of them end up simply quitting competitive aikido training?

Most remain in competitive aikido as instructors. Some also start putting a lot more energy into working with our katageiko system, which is actually quite extensive. Others may become referees since there’s always a need for experienced people to do that. They can stay involved in ways like these and thereby contribute to expanding the competitive aikido community. Tomiki Sensei said, “That which is good will spread.” But it’s probably also true that even good things will have trouble spreading if people stay silent about them.

What are some of your hopes for the future?

I’d like to see across-the-board improvement in everything we’re doing. Places where the level is too far from our ideals will have a hard time moving to the next step.

Tomiki Sensei never said that the knife randori we use should be considered a completed or perfected method. I don’t think it is, either. So, it’s important to work on improving what we’re doing overall, so that we can start taking the next steps needed to move all at least a little closer to perfection.

For one, the techniques being done in competition have become much cleaner, and you hardly see anyone getting their feet all tied up together like they used to. Sacrifice techniques aren’t used so much anymore, either. Sacrifices where you fall over and then apply your technique from there are not used in our competitive matches.

I’d also like to increase the numbers of competitors, to have as many people as possible participate in competitive aikido. Katageiko is great practice, and very interesting and of course very challenging in itself, but that other wheel of the cart, randori, is also a lot of fun and interesting in its own way. Mr. Komatsu,* as a member of the refereeing committee, what do you think?

*Masaharu Komatsu, former Shimpan Staff Chief, PR representative

Komatsu: Tomiki Sensei always said we should do whatever we can as well as we can. So we can start with whatever we can do now and steadily make improvements from there. Even matches that turn out poorly we can still learn from. Matches are inherently like that; they serve as a place to test and verify things. Our approach it to test things through competition and reflect the results back into our training system. If a match turns out poorly, we don’t just judge that match, but rather look to see if the form behind it was at fault, and if so we make improvements and try again. Our task is to find ways to develop and perfect the training method Tomiki Sensei taught us.

Another thing I would mention is that striking techniques have changed considerably since that first tournament. I think we’ve seen some real progress there. They’re now much more capable of downing an opponent without injuring him, which is something that I think is difficult to achieve in other budo.

The kinds of rules and such among other groups who do matches are largely the kinds of things that we’ve already devised and revised through our own process of trial and error. Refereeing skills, too, have been improving as we find better and better training methods.

I agree. And as I mentioned earlier, the reason so many people who heard Tomiki Sensei’s talks are still with us today has to do with the fact that there are people at the center who have put everything we do through a long process of trial-and-error and accumulated the results.

In 1978 and 1979 Tomiki Sensei gathered those who were central people at the time to attend seminars called All-Japan Instructors’ Seminars in his hometown of Kakunodate in Akita prefecture. In the pamphlet distributed at the 1979 seminar he wrote: “There are some who name me as the originator of competitive aikido, but such is not the case; it is, rather, all of those practicing today who are the real originators.” I think it was this kind of attitude that so strongly captivated so many of the students training back then, because it wasn’t the kind of thing you’d ordinarily hear from a teacher. Most tend to “I’m the top” and leave it at that. But Tomiki Sensei never said that.

Thank you very much!

[translated by Derek Steel]

Add comment