The following article was prepared with the kind assistance of Jim Sorrentino of the USA. Interview date c. 1985. Mitsugi Saotome Sensei will be included in our upcoming Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, limited edition book. You can preorder a copy here until December 30, 2022.

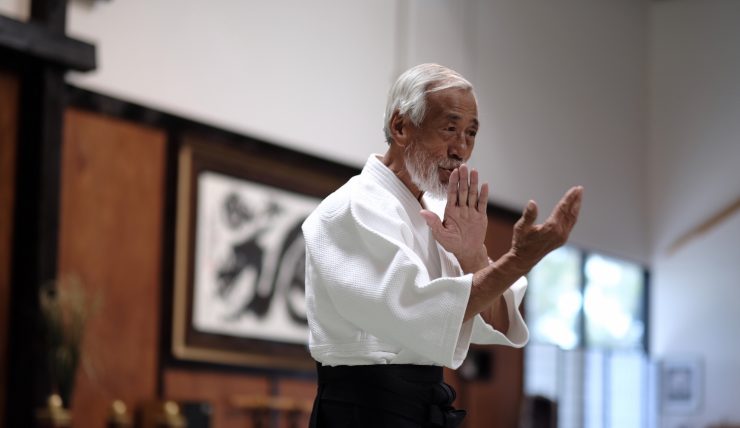

Mitsugi Saotome Shihan is well-known in the United States as the founder of the Aikido Schools of Ueshiba. In the first half of a two-part interview, Saotome recalls his fifteen years as uchideshi at the Hombu Dojo, sharess his impressions of O-Sensei, and discusses his approach to weapons training.

Aikido Journal: Could you tell us about your aikido background?

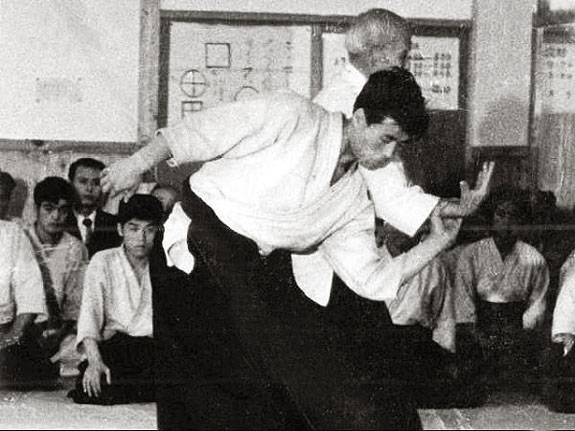

Saotome Sensei: I practiced judo when I was in high school. I was taken to the Kuwamori Dojo with an introduction from my judo teacher because he thought aikido would be suitable for me. That’s when I learned about aikido for the first time. At that time Seigo Yamaguchi Sensei was teaching the class. I was bigger than I am now and weighed about 190 pounds. I used to win judo matches in Tokyo. After the class, Yamaguchi Sensei told me to grab his fingers. The moment I grabbed them I was thrown. I didn’t know how it happened and thought I had fallen by myself by tripping on a corner of the tatami mats. So I asked him to do it again. I think I was thrown four or five times. He threw me with his fingers and also when I grabbed his shoulder. This is how I started the art. After the class I talked with Yamaguchi Sensei and Kuwamori Sensei not only about martial arts, but also about various things such as Oriental philosophy. I was very glad to be able to do so because I was hungry for discussion on such topics to help me in my life. I still respect Kuwamori Sensei and I was very impressed by Yamaguchi Sensei. So I entered the dojo while continuing to practice judo.

Was this after Yamaguchi Sensei had returned from Burma?

No, it was before he went. The Kuwamori Dojo was the first Aikikai branch dojo after the war. In those days, Aikido Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba also used to come to the dojo, although we called him “Wakasensei” then. I imagined that he would be a typical martial-arts type but he looked like a university professor and spoke very politely. He impressed me as quite a gentleman. I was surprised to see his thick, strong hands. He was different from judo teachers. I spoke with him about many subjects and came to appreciate aikido even more.

In those days Wakasensei was still employed by the Osaka Securities Company. I have been doing aikido since that time. Shoji Nishio was also present. And Nobuyoshi Tamura started three months before I did. This happened about 37 years ago [ca. 1954]. I wanted to become an uchideshi but that didn’t happen until 1961. In those days Tamura was also working outside even though he was an uchideshi. It’s not like today when the dojo gives the young teachers a salary.

When I first met O-Sensei I was a high school student. I practiced in the old Hombu Dojo. The dojo wasn’t dirty but the tatami were worn out. O-Sensei, with his white beard, was talking to his students. I didn’t know who O-Sensei was then. O-Sensei spoke to me first to welcome me while the people around him were very tense. I was very surprised and felt a tingling feeling in my spine. I don’t know whether or not you could describe it as a spiritual awakening, but I was very shocked. In those days I personally visited teachers of other martial arts, not only from judo, but they were all different from O-Sensei. O-Sensei was in his sixties then and was dignified. It was a wonderful opportunity for me to be able to meet him. He impressed me very strongly and this made me feel that I could give up everything to learn under him.

Was it mainly Wakasensei who was instructing at the Hombu Dojo at that time?

Wakasensei taught morning classes and then went to work. Yamaguchi Sensei taught the most.

Were there classes in both the morning and evening in those days?

That’s right. But there weren’t many classes in the beginning. The number increased gradually. In those days I participated in the 8:00 to 9:00 a.m. class which was usually taught by O-Sensei. If ten students showed up, the present Doshu commented on the large number of participants. He was still young then. I remember we used to practice kakarigeiko (training with continuous attacks) with Doshu. Nowadays aikido is known, but in those days many people asked what aikido was, even in Tokyo.

When I became an uchideshi O-Sensei scolded me more than anyone else. I was an uchideshi for almost 15 years and maybe that’s why he found it easier to scold me. I was the clumsy type while other uchideshi were much quicker than me to learn. I was the last to remain as an uchideshi.

“In my opinion, while O-Sensei was alive the art changed year after year and was continuously evolving. I wanted to observe O-Sensei while he trained himself. That’s why I stayed the longest as uchideshi [laughter]!”

Did you learn the sword from O-Sensei?

In the old days the shihan took turns teaching on Sundays. I think O-Sensei became bored one day and said, looking into the office, “Who’s here today, Saotome?” He told me to shut and lock the windows, and I wondered what he was thinking. Then he ordered me to bring a bokken. “This is a sword kata for use in a real fighting situation,” he said, and showed it to me. His way of thinking was very old-fashioned. He ordered me to close the windows so nobody would see him. “You will never become a master,” he said [laughter]. I couldn’t understand at all. That kata was slightly different from the kumitachi. He showed me the kata very quickly in about five minutes.

A number of years ago, when I watched you train, Sensei, you were using the bamboo sword of the Yagyu-ryu, I believe. Do you still use it in your practice?

All my students use it. The reason I use the Yagyu-ryu bamboo sword is if we use the bokken to learn the basics of the sword and the kata, we can hurt our fingers and so we experience fear. If we are actually struck by a bokken we will be injured. So we really don’t want to strike each other. If we use the bamboo sword we feel safe to a certain extent, because if we are struck by it we won’t be injured. Even though we feel pain, we won’t suffer any broken bones. So we will be able to reach a certain level of skill quickly. If we use a bokken we are sure to become tense. If we use the bamboo sword, we can relax and practice without hesitation. Later we use the bokken. In that way students can master the kenand kumitachi. If we practice without any danger of injury, however, training becomes very haphazard. We have to be very careful about how we hold the sword in order to avoid injuries. Somehow we are not able to develop the true feeling of the kumitachi. It ends up only being a kata. You’re not able to harmonize or move your ki at all. So I have my students use the bokken after mastering the sword up to a certain degree. Since they are used to it, they can control the sword. Thus, we train in a step-by-step manner.

Morihiro Saito Sensei, for example, has organized the ken and jo movements he was taught by O-Sensei. What are the kumitachi you devised for “Aikido Schools of Ueshiba” like?

O-Sensei’s way of teaching varied according to the situation. The people who were taught by O-Sensei do the ken and jo differently. Since O-Sensei’s sword was the sword of aikido it is difficult to comprehend. You always had to follow him closely. It was necessary to systematize his teaching yourself. When I saw Morihiro Saito Sensei’s ken and jo at the Friendship Demonstration, I thought, “Yes, O-Sensei taught that too.” But somehow it was different. Saito Sensei has organized well what he was taught. My sword method and way of doing the kumitachi is also a bit different. This is because our experiences are different.

This is something that Shoji Nishio Sensei said clearly. At that time the emphasis in teaching at Hombu Dojo was on taijutsu(empty-handed) training, but the ken and jo were also considered important. However, there was no one at the Hombu Dojo who taught the ken and jo in the old days.

O-Sensei taught [ken and jo] during seminars at that time. He taught the basics. It is not proper to say this, but people who came to the dojo from the outside were guests. The students were the uchideshi who served O-Sensei. Since those coming from the outside were guests we took good care of them. The guests were not scolded even if they made the same mistakes we did. If I made the same mistake I was really given a hard time.

At the present time I am teaching in America, but I have never taught students by telling them they don’t understand. I don’t know about the training at Hombu Dojo now, but I have my students do more than is required in training in Japan. I teach them how to use other things besides the jo and ken. We also use our own weapons in addition to what we learned from O-Sensei. For example, we use such things as sticks. These are all a part of aikido. The important point with this is that our way of using the ken and jo is as a method of aikido training. We are not kendoka, or jo practitioners. They are used as a way of training. I often remind students that there must be no misunderstanding about this point.

Practitioners of traditional martial arts, kendo, and iaido often criticized O-Sensei’s ken and jo. His approach to the sword was somewhat different. I believe that the particular way of using the hips and stance adopted by the founder to avoid aiuchi(mutual striking resulting in injury or death to both parties) do not exist in iaido and kendo.

Yes, there are such people among practitioners of traditional martial arts. There are also some among those doing Yagyu-ryu. Irimi is one of the best ways to avoid aiuchi. You enter and lead your opponent’s sword. This is something that O-Sensei would say often: “Thrust against a thrusting sword!” He said that the opponent’s attack would show you the way and you should follow it. This is irimi in a spiritual sense. Even aiuchi ends up being irimi. It is a form of prayer. “You win by entering and leading your opponent’s spirit,” O-Sensei would say. So it’s not a matter of sword fighting. Then you naturally connect with your opponent. In this respect O-Sensei’s way of thinking was very scientific. He often spoke of the kamisama(deities) and of spiritual matters, but his way of thinking was also very rational and scientific. Also, I think it’s natural from the viewpoint of practitioners of traditional martial arts to criticize him because O-Sensei’s sword was different. This is because O-Sensei developed this sword method himself. O-Sensei had a menkyo kaiden(advanced certificate of proficiency) in various martial arts and took the essence from them to develop his sword technique.

“It is meaningless to think that O-Sensei’s ken is different from other martial arts. What O-Sensei did was build on this base and create something new.”

It is possible to criticize the past, but the past cannot criticize the future. It is a different dimension. Even if someone says that O-Sensei’s sword was different from the traditional sword arts, the fact is that he was not trying to do a traditional sword art.

Historically there was a close connection between the sword and empty-handed techniques. They were all practiced together then, but little by little specialists emerged and they became separated. You had to be able to use the spear and the sword, execute empty-handed techniques, and be skilled at horsemanship, since they were all combined. The sword had to have associated empty-handed techniques. Learning empty-handed techniques meant learning sword techniques. For this reason, kendo, karatedo, and judo did not exist in the old days.

I would imagine there must be some difficult aspects about teaching aikido in the United States.

I don’t use Shinto terminology like O-Sensei did. However, science is a universal language and is something anyone can be persuaded by. If highly specialized religious words such as “kannagara”(the Way of the Gods, Shintoism) are used, they are not universally understood. I have avoided such terms.

It is difficult for me to say clearly that you need to study if you want to learn about Japan. After all, I have to make my students understand. Since there are many people who want to understand I must make an effort to achieve this. I believe that it is necessary to make great efforts to introduce Japanese culture to the people of the world. Foreigners don’t understand about Japan. On the other hand, it is not necessarily true that Japanese understand Japan. Japanese are foreigners even while living in their own country. Just because you live in Japan and speak Japanese doesn’t mean you understand the true roots of the nation. I think there are a lot of people like that. For example, Japanese who travel abroad to study don’t understand everything about Japan even though they think they do. They don’t know about the tea ceremony. They don’t know about archery. There are many Japanese like that.

Some seven years ago, when we were interviewing an aikido shihan, he said, “Even if a foreigner comes to Japan to train, there is no way he can understand the true meaning of aikido. Due to language and cultural differences, foreigners cannot understand the spiritual meaning of the art.” When he was questioned about this, our conclusion was that it was difficult even for Japanese to understand it.

Well, that’s true. Even though I have been practicing for more than 30 years I’m still not at the point where I understand it. I’m just now understanding things that O-Sensei told me many years ago. It’s a question of the extent to which one understands. I feel the same way you do. I know of one teacher who went abroad and said, “Aikido is the essence of Japanese culture and therefore foreigners can’t understand it.” I very much dislike the word “foreigner”, anyway, but I wondered what he meant. Why did he bother to go abroad to teach aikido?

“What can one say about someone who teaches aikido to people who don’t understand it for many years? It would be better for him to return to Japan. I think it’s disgraceful to say that sort of thing. If you can’t do something to help your students to understand it means you yourself are incompetent. It’s a way of shifting responsibility onto someone else. You’re making the students responsible for your failure.”

Of course, there are students who don’t understand, but even in Japan there are students who study for many years and don’t understand. What would he think if someone said that Japanese don’t understand Beethoven? I wonder why the difficulty in understanding should be any different with traditional Japanese arts.

In my viewpoint aikido is not a traditional martial art. It is a new martial art. I think that O-Sensei’s approach was revolutionary.

Yes, his concept was splendid. It is the most revolutionary idea since the beginning of martial arts. In bujutsu it is considered acceptable to defeat an opponent in order to protect oneself, but I think that bujutsu and budo are different. What people usually talk about is not budo, it is bujutsu. In bujutsu it is sufficient to explain how to do techniques. As you have no doubt experienced yourself, at the beginning of your budo training it was difficult to understand the theory. Because you couldn’t understand the concept of budo, your body didn’t move properly. Why must we harmonize with our partner in budo and execute tenkan? Originally there existed no way of understanding the concept of budo through open handed technique alone. Some teachers who practiced other types of budo for many years understood. However, aikido students practice techniques which contain the essence of the art from the beginning. Tenkan, in addition to being a technique, is also a philosophy.

Can this way of thinking be found in the history of religion? For example, are there some points in common between the thinking of Christianity and aikido? The idea of protecting oneself without defeating an opponent, for example.

I think that you find this kind of thinking to a certain extent in Shinto, as part of its spiritual roots. It would take a long time to explain it, but the idea of mutual prosperity does exist. O-Sensei’s budo did not originate from bujutsu. He studied various bujutsu, but, in the end, he developed a form of empty-handed technique from a religious viewpoint. Of course, he learned old forms, but the development of aikido was due to the influence of kannagara no michi. This is not Shintoism; it is the Way of the Gods. This spirit is expressed in the techniques. So it is religion and at the same time it is not religion. It seems like I’m playing with words, but that’s the way it is. O-Sensei said, “Aikido is not religion, but it is exactly the same. Aikido is the bible I am bequeathing to posterity.” O-Sensei laid the greatest emphasis on breathing and ikkyotechniques and on irimi and tenkan. He also stressed the concept of “musubi”(‘tying’ oneself to one’s partner).

Training in breathing, while being a form of physical training, is also a form of mental and philosophical training. It is not something to be thought of with the mind, but rather experienced with the body. O-Sensei was a genius to have conceived this kind of educational system. To put it simply, in addition to being a budo, aikido is an educational system. While you teach others you teach yourself. We practice not only outwardly but inwardly.

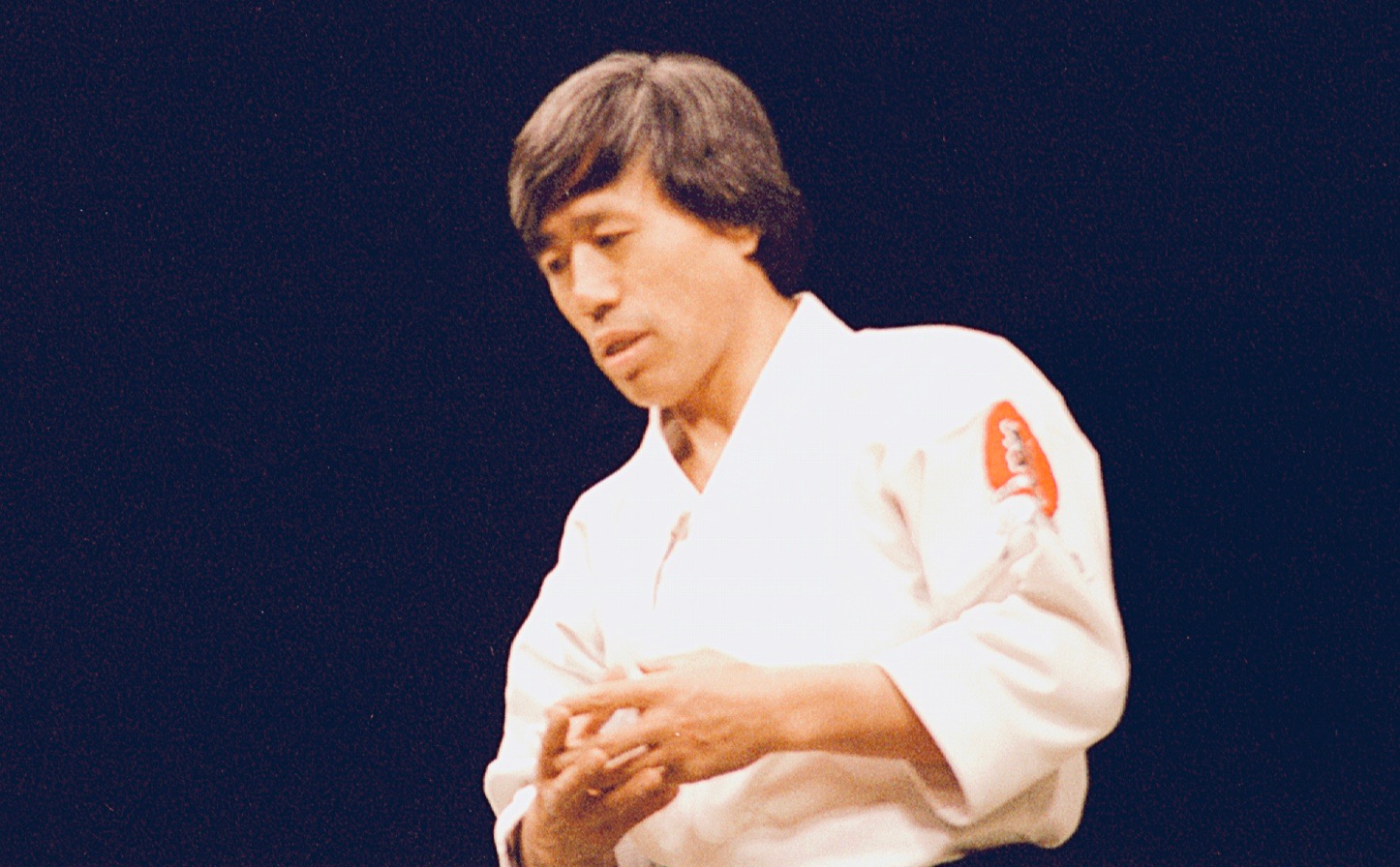

Profile of Mitsugi Saotome

Born in 1937. Aikikai shihan. Began aikido ca. 1954 at the Kuwamori Branch Dojo and entered the Hombu Dojo as uchideshi in 1961. Arrived in the United States in 1975 and subsequently established the Aikido Schools of Ueshiba, an originally independent organization which, since January 1988, is recognized by the Aikikai Hombu. Author of numerous books on aikido, he travels extensively throughout the United States.

Add comment