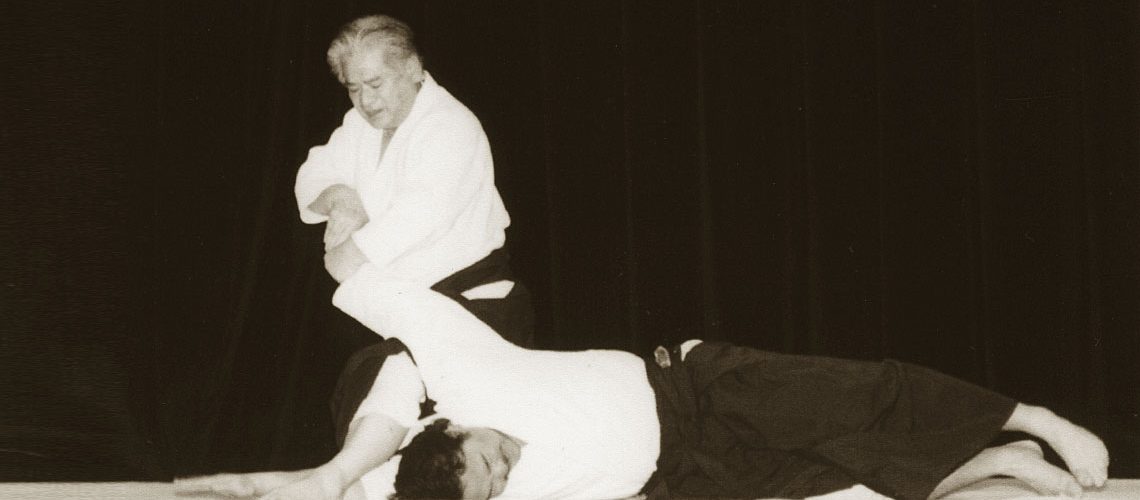

“Arikawa Sensei was talkative, tireless, severe yet cheerful, fearsome on the mat, and fiercely loyal to the Ueshiba family.”

On October 11, 2003, the aikido world lost 9th dan Sadateru Arikawa, one of the few remaining giants of the postwar generation of instructors that played a predominant role in the dissemination of the art worldwide. I had the pleasure of knowing and associating with this enigmatic figure over a 33-year period. During that time he taught me a great deal about Japanese martial arts history, research methodology, etiquette, and the ins and outs of the aikido subculture. Arikawa Sensei was talkative, tireless, severe yet cheerful, fearsome on the mat, and fiercely loyal to the Ueshiba family. There was no one more knowledgeable than he on all things aikido-related. He was a walking dictionary and a martial arts’ historian par excellence.

In this tribute, I will endeavor to provide an insight into this colorful figure by describing some of the highlights of our long association.

I initially encountered Sadateru Arikawa on my first trip to Japan in the summer of 1969. His reputation of being ferocious on the mat had preceded him and I wasn’t disappointed when I participated in one of his classes for the first time. With a big smile on his face he would apply painful joint-locks (kansetsuwaza) and powerful throws to any and all who would knowingly or foolishly volunteer a limb. I think I only attended two or three of his classes during that summer figuring that I would be tempting the hands of fate if I trained in his class on a regular basis.

At that time, there was a series of cartoons drawn by a British aikidoka circulating at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. The drawing depicting Arikawa Sensei showed the figure of a cowering student crawling underneath the tatami in order to escape treatment at the hands of “Harry”–a pun on the first three letters of his name and a reference to his thick, black shock of hair–as Sensei was affectionately known among the foreigners at the dojo.

Our next encounter took place in 1973 when I again visited Japan over the year-end holidays. I have a single memory of him from that time. I ran into Arikawa Sensei near the office at Hombu Dojo one day and he proceeded to chat with me about aikido history. He seemed to know of my deep interest in that subject and cheerfully carried on. My Japanese was very basic at that stage and I was only able to understand a little of what he was saying. But this was to prove the first of scores of conversations we would have over the years that would prove so valuable to me in my historical research.

My move to Japan in 1977 marked the beginning of our first meaningful interaction. Around 1978 I had discovered a copy of the old Asahi News film of O-Sensei taken in 1935. During the Iwama Taisai of that year a string of visitors came by my house in Iwama near the dojo to view this rare old film. Among them to my surprise was Arikawa Sensei. He ended up spending several hours at my home and flattered me by saying that he preferred to stay and talk about aikido history rather than return to the dojo and participate in the party festivities after the religious ceremony. Sensei was not in good health at that time and had been off the mat for about a year on doctor’s orders. He had lost a lot of weight too, but eventually made a complete recovery to resume his instructional duties which included Wednesday evening training at the Aikikai for several decades.

In the early 1980s I moved to Tokyo from Iwama and Arikawa Sensei was a frequent visitor to my home which also doubled as an office in Yotsuya Sanchome, not far from the Aikikai.. He would suddenly call up saying he was in the neighborhood and ask if he could stop by. Sometimes we would spend six or seven hours together and end up going out to dinner. The conversations were always centered on aikido, O-Sensei, Aikikai politics, the publication of Aiki News, and related subjects. Arikawa Sensei truly had a photographic memory. I used to be amazed at how he would walk into my room filled with books and documents and proceed to scan their contents. Sensei would often spy a new item out of the many documents and ask if he could take a look at it. It seemed he had memorized every book, photo and paper in our archives.

My staff would dread these visits by Sensei because it would interrupt their work flow. Also, no one other than me had such an unquenchable interest in aikido history that I shared with Arikawa Sensei. Besides, many people found it difficult to understand his speech, myself included, because he talked in a scarcely audible, raspy voice. I never could figure out why Sensei talked in this way until much later when he told me the story.

It seems that as a student in elementary school he got into a fight during which he sustained an injury to his throat. This required an operation and he was hospitalized for a month. From that time on his larynx was damaged and it hurt him to attempt to speak in a loud voice.

In any event, even though it was sometimes tiring, I was always willing to spend long hours with Sensei whenever the opportunity presented itself. Arikawa Sensei would often sometimes assume the role of mentor especially in matters dealing with aikido politics. I didn’t always follow his advice, but at least he gave me another viewpoint to consider. No matter what question I would ask about the Founder, aikido techniques, or martial arts in general he had a detailed answer. It seemed too that he knew and had talked with most major figures in the aikido, Daito-ryu, and kobudo worlds.

As our relationship deepened over the years, he adopted an interesting pedagogical approach he would use in our conversations. If I were to ask him his opinion about some historical matter concerning aikido, he would not give me an answer immediately. Sensei would in turn respond with a question of his own attempting to get me to think analytically, consider different possibilities, and proceed by process of deduction. He obviously enjoyed doing this to me and I often felt like a schoolboy trying to keep up with his brilliant intellect.

As the years passed and more and more of the aikido old-timers left this world, especially following the death of Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba, I think we both realized that the kinds of things we talked about were of interest only to a few people. In fact, on certain topics, Arikawa Sensei was the only person I could speak with meaningfully.

In the mid-1980s, Aiki News sponsored a series of events called the “Aikido Friendship Demonstrations” in Tokyo. These demonstrations proved to be rather controversial since we invited teachers from different organizations to share a common stage. Sensei would give me advice and explain the view of the Aikikai towards this event. He was sometimes critical of my actions, but I always valued his perspectives. He attended each and every one of these events usually standing in the back of the auditorium in his capacity as a “spy,” to use his words!

As a consequence of the Third Friendship Demonstration held in 1987, I became acquainted with Katsuyuki Kondo Sensei of Daito-ryu aikijujutsu. Kondo Sensei was one of the most senior students of Tokimune Takeda, Headmaster of the Daito-ryu and, as it turned out, a close friend of Arikawa Sensei due to their connection with Chiba Kogyo University. The three of us would often encounter each other at the All-Japan demonstrations, various aikido and Daito-ryu events, and several times at Kondo Sensei’s home. There was a camaraderie between Arikawa and Kondo Sensei and, when I was together with them, I fancied myself as one of the “Three Musketeers” of the Aiki world–surely a gross exaggeration of my importance! We took photos of the three of us on a couple of occasions which I highly prize.

On one occasion about 1998, I came up with a plan that I hoped would convince Arikawa Sensei to begin writing articles for Aiki News. Sensei had served as the editor of the “Aikido Shimbun,” the monthly publication of the Aikikai, for the first years of its existence. Despite this, I don’t know if he ever penned any articles in his own name other than a few short pieces appearing in that newsletter. As I knew Sensei was in the process of organizing his vast collection of documents, I wanted to lend our support to him and get him to commit his thoughts to paper since he was already in his late 60s. I strongly felt that one doesn’t just write a masterpiece the first time around, and I was concerned that Arikawa Sensei would wait too long before beginning his definitive book on martial arts history.

Anyway, Kondo Sensei agreed to cooperate with this plan and the three of us met at a restaurant near Kondo Sensei’s home. He talked to Arikawa Sensei on my behalf of the importance of getting started with his writing and urged him to accept my offer to publish in Aiki News. Arikawa Sensei appeared to give the idea some consideration, but would not commit to any specific arrangement. As it turned out, nothing came of this proposal, but that didn’t keep me from bringing up the subject whenever we met. His answer was always the same “Ima seirichuu dakara, mada hayai” (“I’m still organizing things, so it’s too soon to talk about that”).

It was certainly true, I think, that he felt he had not yet sufficiently organized his ideas, but it was also true that he was not in a position to appear in Aiki News due to his important posts within the Aikikai and closeness to the Ueshiba family. The latter disapproved of certain aspects of our activities and publishing practices. We both acknowledged this reality and it remained a constant theme underlying our long relationship. One of my great regrets was that we could never receive permission from Sensei to publish an early interview I conducted with him back in 1980. Perhaps it will finally be possible to do so posthumously.

The months immediately prior to my return to the USA in 1996 through 2002 was the period of time when I had the most contact with Arikawa Sensei. On most of my trips to Japan I would contact him and he would come to the Aiki News office in Odakyu Sagamihara. He would arrive around 5 pm and stay until about 9 pm when we would go for dinner. I religiously recorded all of these conversations and have many hours of our exchanges that I hope someday to organize. As I mentioned above, each time Sensei would come I would ask him about his progress in organizing his documents and encourage him to at least write up some kind of an outline of the book he was planning to write. On one occasion, he described some of the areas he would cover in his book which was generally about the martial arts background leading up to the creation of aikido.

In January 1999, the Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba passed away after a long illness. I hastily made plans to travel to Tokyo for the funeral. On that day, Arikawa Sensei did something to assist me that I will never forget.

I arrived about 45 minutes early even though I had intended to show up long before this time because it was such an important event. I then proceeded to stand in line waiting to enter into the hall where the ceremony was being held. There were at least 2,000 people in line in front of me! I resigned myself to only being able to cover the event from a distance.

Then after a half an hour or so and to my great surprise, Arikawa Sensei came trudging down the hill where the line had formed looking for me. He came up to me and grabbed my arm and started leading me up the hill past the reception table and right into room where the VIPs were gathered to pay their final respects. Smiling broadly, he told me to take lots of pictures and write up a good report since this was such an historic event. He certainly had a sense of history and was thinking far into the future. I was truly humbled by his kindness.

On one of my trips around 2000, I was really pressed for time and could not meet him at my office as usual. I decided just to show up at Hombu Dojo on a Wednesday evening and view part of his class and say hello. For me watching him that evening was a revelation because his techniques had become completely transformed. Gone was the ferocity of technique that was his trademark, to be replaced by soft, blending movements. What had the world come to? Arikawa Sensei had become soft!

Sensei didn’t see me at first but when he recognized me he came over with a big smile on his face. He indicated that I should wait for him after class downstairs. Following the end of training, I went downstairs and was ushered into the side office near the entrance of the Hombu Dojo. I was served green tea as I waited for Arikawa Sensei for about 15 minutes. Sensei changed into his street clothes and met me in the office where we proceeded to launch into one of our typical conversations. We chatted for about 30 minutes or so and I started to feel a little uncomfortable because it was clear that several of his students were waiting for him outside the door to the office. I remarked to Sensei that I was sure he was busy and that his students were probably anxious to leave. He said with a smile on his face, “Let them wait a little longer.” We continued for a few more minutes and I asked him the following question “Sensei, are there any among your students who are interested in the subjects that we talk about?” He replied that there weren’t and that he just spoke of these things with me. I was taken aback by his answer and it made me feel sad for him that he couldn’t engage in these kinds of conversations that he so obviously enjoyed with others.

After that evening, I met him two or three times on subsequent trips to Japan. Then in early 2003 I received a phone call from Kondo Sensei who reported to me that Arikawa Sensei had been ill and was stepping down as the chief instructor of the Chiba Kogyo University Aikido Club after more than 30 years. Shortly thereafter I called the Hombu Dojo on a Wednesday night hoping to reach him. Fortunately, I was able to talk with him and expressed my concern over his health and asked how he was doing. Sensei minimized the extent of his illness and said that he was continuing to teach at Hombu Dojo and would now have more time to concentrate on writing. He sounded just like his usual self and I felt somewhat reassured. That turned out to be the last time I would ever speak to him.

In October I received another call from Kondo Sensei saying that Arikawa Sensei was hospitalized and near death, but that I should keep his condition secret at Arikawa Sensei’s specific request. By coincidence, this was just two or three days before my next scheduled trip to Japan. Immediately on my arrival in Japan I went from Narita airport to the hospital where Sensei lay sick. When I arrived no one was there and I found him in a semi-coma. I talked to him and he seemed to recognize me and hear what I was saying, but I have no way of knowing since he was unable to respond. I visited him two more times, the last accompanied by Peter Goldsbury just a few minutes before Arikawa Sensei passed away. It was sad to see him come to the end of his life without having written his masterpiece, but I was at least thankful to have had the opportunity to say my final respects to him.

As close as I was with Arikawa Sensei, he will always remain an enigma. He was extremely intelligent and perceptive and yet preferred to remain in the background. He was a prodigious reader and collector of old books, and an enthusiastic photographer and videographer. Sensei was completely devoted to the Founder and his son, the late Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba and served the Ueshiba family for some 50 years. Privately, he was rather critical of the superficial training practices common in many dojos and, in that respect, we shared the same opinion. In fact, his withdrawal from participation in the All-Japan demonstrations way back in 1973 was, I think, related to this fact.

It’s hard to predict what place Sadateru Arikawa Sensei will occupy in the written histories of aikido due to his eccentric nature and tendency to avoid the spotlight. Yet those who knew him cannot fail to appreciate his uniqueness as an unsurpassed authority on every aspect of aikido and his long, devoted service to the Aikikai. For me personally, Arikawa Sensei represents a height I can never attain to given his direct association with the Founder and first-hand knowledge of key historical events. He was a constant guide that helped me understand the subject of my research to a much greater degree and I believe in my heart that he supported my work. During our conversations, I sometimes had the feeling that he knew he would never finish the huge task that lay before him, but knew that he could count on me and a few others close to him to keep his memory alive.

December 16, 2003

Las Vegas, NV, USA

El mundo del Aikido siempre recordara el excelente trabajo de Sadateru Arikawa.

He sounds like a one of a kind Aikidoka. Thank you so much for honoring him and for sharing your experiences with him through this blog. I hope in time you will be able to share more interviews and documents about him, although I understand keeping your promise to him as well.