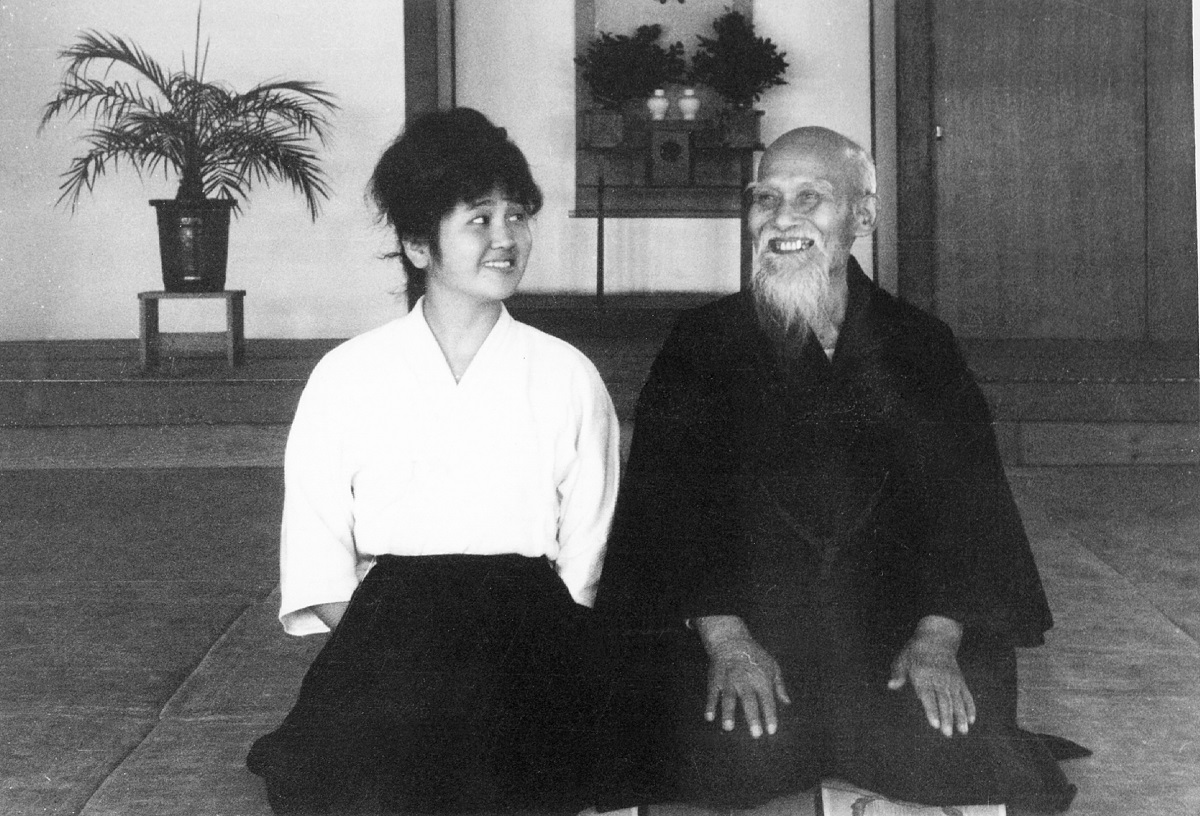

In 1960, a vivacious young Japanese woman joined the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo and fell under the spell of the charismatic Founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba. Mariye (Yano) Takahashi gradually became a confidant of the Ueshiba family and the Hombu uchideshi forming bonds of friendship that continue to this day. Takahashi later sought a new adventure in America and ended up contributing significantly to the development of aikido in Southern California. Now an accomplished writer and university professor, Takahashi has contributed articles on a wide-range of topics for a variety of Japanese publications. In part one of this fascinating interview, Takahashi paints a vivid portrait of O-Sensei and offers an informed perspective on the founder’s Shinto-based belief system. This is the first in a two-part interview. You can read the second part here.

I understand you were born in Manchuria. Would you start by telling us a few details about your family?

At the time my father was the president of Manchuria Antoo Zooshi, a paper factory in Manchuria which was a branch of the Ooji Paper Company. He was on friendly terms with a General of the Japanese Imperial Army, Yasunao Yoshioka, who was one of those responsible for establishing Manchukuo and the position of Puyi*, known as the last Emperor.

*Puyi (J: Fugi), installed as an infant as the last Manchu emperor in China, forced to abdicate in 1912 at the age of six. Puyi installed in 1932 as chief executive of the Japanese-sponsored state in Manchuria, a purely ceremonial position controlled by Japanese advisors.

As World War II expanded, the industries in Manchuria became increasingly important to Japan, and my father’s factory was one of those toured and inspected by Puyi. General Yoshikoka once came to our house for dinner with some of the officers under his command, and I remember when I went out to greet them in our guest room, he gave me some sweets wrapped in Japanese paper.

We eventually had to leave Manchuria as the war came to an end. I remember one of the only things we took with us was a hanging-scroll ink painting that General Yoshikoka had done and given to my father. It’s still in the family, in fact, as one of our treasured heirlooms.

I believe your family went from Manchuria to Kyushu after World War II. Is that correct?

Yes, we had to relocate to my mother’s hometown of Fukuoka. That’s where I grew up.

When did you relocate to Tokyo?

When I was eighteen, after graduating from high school. I entered a university, but back then I don’t think I understood the potential inherent in the so-called “intellectual life,” and I tended to be more drawn toward things of a more spiritual nature. I was always seeking something in that vein, in that idealistic, righteousness way that young people tend to have, always letting my daydreams get ahead of me. What is interesting, though, is that ever since I was in middle school I’d been having this dream – or more than a dream, it was something I was actually quite certain of – that someday I would encounter some kind of “superhuman” individual, and that eventually I would reap great fruits from that encounter.

It happened that my elder brother Kazunari Yano was friends with Tetsuo Yoshizato (former Operations Bureau Chief of the Nishi Nihon News and an acquaintance of Kisshomaru Ueshiba). He was practicing aikido and he recommended it to me as something well-suited to women. That was in 1960, back when the old Hombu Dojo was still a traditional residential-style building. As soon as I opened the door, an uchideshi garbed in a splashed-pattern kimono and hakama came rushing out into the small foyer from the front room to greet me. It was Kazuo Chiba [currently of the San Diego Aikikai]. He didn’t have a samurai top-knot, but in all other respects I was sure that I’d run into a real samurai! He dropped into a formal seated bow, hakama pleated immaculately, hands on the floor in perfect form, and said: “Welcome…” I immediately thought to myself, “Oh my, this is it! This must be what I’ve been looking for! There must be something here for me…” (laughs)

When did you finally get to meet O-Sensei himself?

Back then he was still dividing his time between the Hombu Dojo and Iwama. I’d heard a lot of amazing things about him, but still I couldn’t guess what he might be like. I was keen at least to see what he looked like, so I went to the dojo every day hoping to catch a glimpse, but it turned out to be a couple of months before I was actually able to meet him. In the meantime, I went every day to the 8:00 am class (not the 6:30 am one taught by Kisshomaru). There weren’t very many people in that particular class, usually only about eight or so. It was taught by teachers like Nobuyoshi Tamura and Yasuo Kobayashi, and sometimes when there was an odd number of students one of the uchideshi like Yutaka Kurita [Mexico] or Mitsunari Kanai [Boston] would come out to practice with me. It was like a private lesson.

So you trained in the morning and went to your university classes in the afternoon?

Right, but I confess I didn’t attend class much at the Japanese university. I mean, I could get an “A” on the final exam after hardly attending a class at all, and that with my only average intellect. I thought the classes were too easy and unchallenging. Also, while in school, at least, I didn’t have that “searching for something” quality I mentioned earlier, so when I was with my friends the conversation tended to focus on things like fashion or the upcoming school dance or whatever. Still, somewhere inside me there remained that feeling of wanting to do something to cultivate the spiritual aspects of myself, and so I went off to practice aikido or whenever I had some free time, I studied Zen at Enkaku temple in Kamakura. In that respect, my personal lifestyle at the time had more to do with things like aikido and Zen than it did with being a university student.

And eventually you met O-Sensei?

Before talking about that I’d like to mention just one thing: When you asked me to talk about my memories of O-Sensei, it occurred to me that doing so might actually be rather difficult. Talking about memories is something I’ve always considered more appropriate for conversations with one’s close friends and relatives; in this case, though, since I know it’s going to be printed, I have the urge to “straighten my collar” as it were, to make sure that what I say is accurate. This very morning, in fact, I prayed to O-Sensei, telling him that today I was going to talk about him and asking for his divine protection so I might do so properly. In any case, I’ll do my absolute best to avoid putting any of my own imagination into what I say.

When I was eighteen, after graduating from high school. I entered a university, but back then I don’t think I understood the potential inherent in the so-called “intellectual life,” and I tended to be more drawn toward things of a more spiritual nature. I was always seeking something in that vein, in that idealistic, righteousness way that young people tend to have, always letting my daydreams get ahead of me. What is interesting, though, is that ever since I was in middle school I’d been having this dream – or more than a dream, it was something I was actually quite certain of – that someday I would encounter some kind of “superhuman” individual, and that eventually I would reap great fruits from that encounter.

Having said that, I’ll begin by saying that I truly believe that O-Sensei was indeed an incarnation of the deity of budo (budo no kami). It’s not a question of believing or not believing this, it’s just a fact that that’s what he was. For that reason, I sometimes think it may be impertinent or at least inappropriate to make definitive statements about O-Sensei, for example that his personality was like this or like that. “I understand it in such-and-such a way” is problematic because in that case you’re only talking about the knowledge you yourself have gleaned, which runs the risk of fixating your own position. Consequently I want to be very careful about what I say about him. In any case, I can say definitively and with complete self-assurance that O-Sensei was truly not just a “superhuman” individual, but literally a divine incarnation. Particularly from the vantage point of some thirty years later, I still can still feel very clearly the true nobility of his spirit.

Did you feel that way from the very first time you met him?

Indeed I did. You may wonder why I say with such conviction that O-Sensei, who usually conducted himself like an ordinary, good-natured sweet old man, was truly an incarnation of a deity of budo. I’m also sure some people will criticize me and say that I’m being absurd, that I’m unjustifiably putting O-Sensei on a pedestal, unconsciously idealizing and “canonizing” him, as it were, placing him somewhere outside the human realm. It’s a fact, though, that many of O-Sensei’s uchideshi and other pupilspeople who had opportunities to witness firsthand the truly miraculous nature of what he did – invariably are convinced, without being influenced by mere hearsay, that his aikido was so sublime as to have been practically divine.

In the meantime, I went every day to the 8:00 am class (not the 6:30 am one taught by Kisshomaru). There weren’t very many people in that particular class, usually only about eight or so. It was taught by teachers like Nobuyoshi Tamura [currently in France] and Yasuo Kobayashi, and sometimes when there was an odd number of students one of the uchideshi like Yutaka Kurita [Mexico] or Mitsunari Kanai [Boston] would come out to practice with me. It was like a private lesson.

To the extent that he was a living, breathing human being he was of the same flesh and blood as the rest of us; but when it came to techniques and divine principles of aikido he was of a truly different order altogether. In part this must have been because of the severe budo and spiritual training he pursued avidly as a young man, but I also think he must have been born with a certain spiritual nature. There was an aura of sanctity that always surrounded his person and his work of aikido.

All human beings have a soul-like spirit. For most of us, though, the fact that our lives center so much around the material world tends to dull this spiritual sense considerably, and because we live our lives in a three-dimensional world we become bedazzled and bewildered by that world, causing our spirituality to atrophy even further. I may say that our human life has an abundance of materials. Even after our needs have been met, we tend to feel that there is not enough. When we turn ourselves to the human spirit, our attention must shift away for the excessively materialistic. According to the official record, O-Sensei was enlightened by being bathed in a golden light. Further, he was capable of representing a divine and mystical power, exalted far beyond the reach of ordinary men.

The divine power uses a specially “chosen” individual like O-Sensei as a medium. Aikido is the transmission of a sublimely divine principle that aims, in part, to help ordinary people like ourselves become more aware of our inherent spirituality through aikido.

Understanding him in this way, O-Sensei’s great achievement in aikido seems a very natural course of things. He himself had a personality so straightforward and pure that it could almost be considered charmingly childlike. I met him after he had experienced a mystical, spiritual union between god and man and become an increasingly spiritual persona, so I found O-Sensei to be quite different from ordinary people. One of the things I saw in O-Sensei’s aikido was the potential for people to grasp some more noble stratum than is ordinarily accessible to them. Just how far a person practicing aikido today can go toward O-Sensei’s level of achievement (both technically and philosophically speaking) will differ for each person, depending largely on the potential that individual has been born with.

What was it like for you at the Hombu Dojo in your early days there?

As a rank beginner I could hardly do anything. I couldn’t do the techniques. I couldn’t understand things. I suppose you could say I was more or less just there, existing. Kisshomaru Sensei once told me he remembered me being there all the time, so I must have been there a lot, despite being hardly able to do or understand anything. In the beginning, I found it rather unnerving to even go near O-Sensei; he was just so awesome that usually I just watched him from a distance, transfixed. I was always happy to see him, though. He was impressive and I had a kind of admiring longing for his presence.

After training for a while, I finally got a little more used to him and I was allowed to go to his room to bring tea or some little sweets for him. I could visit with him in his room from time to time. Whenever I came in he would greet me with a kind of pure-hearted, innocent cheerfulness. It was a great honor for me to be near him and I was like one of those charming young maidens (Miko) you see serving the Shinto deity at shrines. I remember one time he had an upset stomach and was refusing to eat anything for breakfast. One of the uchideshi told me to go see him, saying that he would probably eat if I were there beside him. When I got to his room he was laying there resting, but as soon he saw me his mood brightened quite a bit. A little later a student from the morning training who happened to be a doctor came in to examine him. He told O-Sensei his stomach was still at least as strong as a forty- or fifty-year old’s and not to worry.

O-Sensei looked happy to hear this and started murmuring something to the effect of “Hmm, I see…” When the wife of Kisshomaru Sensei brought him some chagayu and umeboshi,* he said, “Well, I suppose since Mariko (O-Sensei called me Mariko) is here I should eat a bit…” As long as I was there watching him he kept eating a little bit at a time, but whenever I moved away, to help straighten up the room or whatever, he would stop instantly! (laughs)

* Chagayu, soft rice gruel made with tea, often eaten by those weakened by illness. Umeboshi, pickled plums, a common side dish.

So, I sat there and said, “O-Sensei, please eat a lot of your chagayu, I am watching you.” The doctor also said, “Please have it, it will be good for you.” Hearing that, my heart was at ease. I thought that if he didn’t eat, he would go someplace far away. I was praying that the doctor’s and my efforts would produce a tangible result in his health.

Often when I went to visit him we didn’t really talk much; I just sat and spent time with him. He often offered me nice things to eat, mikan (satsuma oranges) for example. If I didn’t eat the mikan on the table he always looked very disappointed, so I ended up eating a lot of them! Whenever I came in he always pulled out a cushion and told me to sit down, so I always plopped right down without even hesitating or having a second thought! It wasn’t that I hadn’t learned how to behave politely, it was just that he seemed to enjoy that kind of easy-going interaction so much. In that way, O-Sensei was a very gentle, mild-mannered person; or perhaps I should say he has a combination of true purity of mind and wholehearted sincerity. I’m sure if you were to ask the gods themselves, “What kind of person is it desirable to be?” they would probably answer, “Someone like O-Sensei.” He truly was one of those special “chosen few.”

During your visits with him did O-Sensei ever talk to you about mythology or other spiritual matters?

No, not to me personally. But I do remember him speaking about such things in the dojo, or dropping a word or two about them now and then. They always struck me as being a lot like newspaper headlines, and nowadays I spend a lot of time writing, trying to put down the “stories” that go with them, so to speak, trying to come up with some answers. In that sense, I feel like O-Sensei left me with a good deal of homework. I always feel like smiling whenever I manage to arrive at some small personal understanding of one of those “assignments.”

Understanding him in this way, O-Sensei’s great achievement in aikido seems a very natural course of things. He himself had a personality so straightforward and pure that it could almost be considered charmingly childlike. I met him after he had experienced a mystical, spiritual union between god and man and become an increasingly spiritual persona, so I found O-Sensei to be quite different from ordinary people. One of the things I saw in O-Sensei’s aikido was the potential for people to grasp some more noble stratum than is ordinarily accessible to them. Just how far a person practicing aikido today can go toward O-Sensei’s level of achievement (both technically and philosophically speaking) will differ for each person, depending largely on the potential that individual has been born with.

O-Sensei was one of those people with a connection to the spiritual world, who could receive the “spiritual waves” emanating from that world. Certainly his ability to bring himself into oneness with the divine, to become one with the kami, made him an extraordinary individual. Even when he was sitting in his room he always sat properly in seiza, legs folded beneath him, never letting his posture lapse. He was infused with something spiritual, possessed of a kind of divinity, always pervaded by an atmosphere of graceful dignity and nobility. During training he was strict with his own young disciples, and it was natural that he should have been so. Toward ordinary people he was courteous, kind, and gentle. You only have to look at those photos of him smiling or laughing to see that gentleness.

I recall one time after training when O-Sensei suddenly referred to himself as being a “Kannon”.* As he was leaving the dojo, he said, “Oh, today, I have become Kannon-sama.” Students in the dojo laughed in a friendly yet respectful way because they knew that O-Sensei was a Shinto believer. They all remained in the dojo to see him off in the usual way. Many people reflected about O-Sensei referring to himself as the Buddhist figure, Boddhisattva, and it seemed to them that the two didn’t go together.

* Kannon (God of Mercy). Boddhhisattva or Avalokitesvara capable of appearing in many forms, male or female, according to circumstance. There are seven forms of Kannon images in Japan to be seen in temples and museums. In Buddhist belief, Kannon is a savior and compassionate being with a loving heart.

I think he must have been referring to different people in different forms as appropriate in order to insure the achievement of salvation by all sentient beings. O-Sensei called himself “Kannon-sama” reflecting how he felt that particular morning. A similar thing holds true for O-Sensei’s statements.

When he demonstrated fast, smooth movements, everything was perfectly timed. Because his movements were divine, each young man who took a fall was instantly on the mat before I knew what had happened. My favorite technique was when O-Sensei placed his index finger on a young man’s neck just below his ear after completing a technique. The young man would be completely nailed down to the mat by his finger and sometimes his face would become red and he would start panting. O-Sensei always asked, “Are you alright?” It seemed that the young man was pinned down with big, invisible nail and could not move.

O-Sensei’s movements were gentle and highly accurate and there was no waste. While he was teaching he always showed concern for the relationship of the U.S. and Russia. He said that if the two countries would practice aikido and learn about harmony, there would be no conflict and they would stop fighting. I would always be left puzzled when O-Sensei talked like this. At that time the world was tense and it was unthinkable for me that they would do “aikido.” There might be a chance for aikido to take root in the U.S., but not in the Soviet Union where Khruschev erected the Iron Curtain to shroud everything in secrecy.

During practice, one morning, O-Sensei clearly stated, “It is now my belief that Heaven has decided that Russia and the U.S. will become friends.” He added confidently, “I have truly received a grand and magnificent message. You people should wait for the day. It will come soon.” I did not understand what he really meant by this, so I thought that O-Sensei’s honest wishes were always nice. However, the two nations have been practicing aikido for quite some time now, haven’t they?

Often when I went to visit him we didn’t really talk much; I just sat and spent time with him. He often offered me nice things to eat, mikan (satsuma oranges) for example. If I didn’t eat the mikan on the table he always looked very disappointed, so I ended up eating a lot of them! Whenever I came in he always pulled out a cushion and told me to sit down, so I always plopped right down without even hesitating or having a second thought! It wasn’t that I hadn’t learned how to behave politely, it was just that he seemed to enjoy that kind of easy-going interaction so much. In that way, O-Sensei was a very gentle, mild-mannered person; or perhaps I should say he has a combination of true purity of mind and wholehearted sincerity. I’m sure if you were to ask the gods themselves, “What kind of person is it desirable to be?” they would probably answer, “Someone like O-Sensei.” He truly was one of those special “chosen few.”

There were times when O-Sensei would suddenly say things to me that I found incomprehensible, for example, he would talk about “plums blossoming all across the universe,” and how the world will “become a better place with the ascent of Ushitora no Konjin.” Sometimes when he noticed that I hadn’t any idea what he was talking about he would try to console me by adding something like, “Ah, right… such things are still beyond our Mariko…” (laughter) I have so many memories like that.

Seven or eight years ago I was visiting Mr. Chiba and he remarked that I was about the only one O-Sensei ever treated in “that grandfatherly kind of way.” It’s true, my experience with O-Sensei was a precious one, and I feel lucky that it happened when I was so young.

One time after the last training of the year I went with a few others to visit O-Sensei in Iwama. We rode in the car of a someone who worked for an American newspaper, accompanied by his wife and also the wife of Nobuyoshi Tamura. We arrived in Iwama at about 5:30 in the morning on New Year’s Day. Mr. Chiba happened to be staying there with O-Sensei.

O-Sensei was already up and seemed pleased that we had come. As you know, it’s quite cold in Iwama around that time of year, so he busied himself by bringing in some firewood and told us to wait just a moment as he got a fire going. As the sun rose it made sunny spots in various corners of the room, and he kept urging us to stand in these to keep warm. He showed us how we should be in natural solar heat. He often interacted with people in that very natural, friendly way.

Later we all sat around in a circle in the house and ate o-zooni [pounded-rice cake boiled with vegetables in soup, a traditional New Year’s Day dish]. O-Sensei was very considerate of his wife, biting off small pieces of the o-zooni and chewing them before giving them to her. She had no teeth and she seemed not to be alert about things around her so he was afraid she might choke on her food. Sometimes I’m asked if I ever saw evidence of true love in their marriage, and I always say that I will never forget that wonderful scene of the two of them together that New Year’s Day.

I believe you once had a chance to look at an important aikido transmission scroll written by O-Sensei.

I don’t remember all of what was in it, but I do remember it had the well-known “circle with a point inside.” It said things like, “Red jewel, white jewel, blossoms of plum… Princesses on the right and left hands… With both hands it becomes one beat, etc.” Thinking about it now, I suspect this teaching had to do with the bipolarity of the divine and the principle of oneness with Nature’s laws as well as the life of natural phenomena emanating from the spiritual realm. Heaven and Earth were created as two aspects of the divine. In other words, there were written descriptions of the philosophical principles of aikido.

For example, the scroll first explained the origins of the circle with the point in it, namely that it can be understood as a stylization of the ideograph character for “Sun” and the Sun in turn can be understood as the root of the universe, since it is positioned at the center of a planetary system.

From a more philosophical perspective – and these are just my own interpretations – if the circle is understood as representing the larger universe, then the inside is the smaller universe, or in other words the self. Further, this “universe” is characterized by and conforms to such natural laws such as “unity” and “structure.” Therefore, by achieving a direct connection between your self and the greater universe, you can obtain the latter’s strength, that is to say, you are then able to take advantage of the divine power that is at the root of the universe. Thus, the circle with the point inside also represents the circular movement of aikido.

Also, while human beings are originally and essentially of a spiritual nature, we tend to become filled with passions and desires and the like, or at least our physical bodies that are of the smaller universe are subject to and influenced by such things. We mistakenly come to think that these are what make up our self, but in fact our true form is that originally given to us by our spirit. Failing to understand this, we become unable to connect ourselves with the greater universe. When people have succeeded in connecting with the universe, that is when truly miraculous, almost divine movements appear in aikido.

If there is a surrounding circle, then the point in the middle is the center. Lacking that center we waver and become unsteady and end up wasting movement and effort; our bodies become like a single solid block, which is not a natural state for us. You can actually judge a person’s psychological and spiritual condition, and to a certain extent even their personality, simply by looking at the way they move their body when doing aikido. In that sense, the circle with the point in the center is extremely important. That sort of thing, too, was described there in O-Sensei’s writing.

According to Shinto practices, the circle represents the mind, or you might say the heart. The point represents the soul. If you loose this soul, then your mind and heart become empty. I now feel that this was one of the things O-Sensei was trying to explain to us through aikido movements.

Something I heard time and again from O-Sensei during training was that aikido principle based on Shinto mythology. In the Nihonshoki compiled in 720, Izanami (male deity) and Izanagi (female deity) wished to become husband and wife and to create nations. The male deity turned clockwise around a pillar and the female turned in the opposite direction. That is, they turned in the opposite directions to what the Sun Goddess requested. They ended up producing a deformed child (Hiruko) instead of creating nations. They had to redo their act in the right way and Yashima (the first name for the Japanese islands) was created.

As years have passed I have always tried to think about what this might mean in aikido. I think O-Sensei was talking about the essence of aikido having to do with following the right way and being in harmony with nature. It seems to me that one should always do the right thing from the beginning. It seems though, that only a few people understood that this was his meaning.

That movement is part of the divine providence of Heaven, something that gets endlessly more interesting the deeper into it you look. The circle with the point in it is one of the simplest, most concise expressions of this. It represents a truly deep philosophy.

From a more philosophical perspective – and these are just my own interpretations – if the circle is understood as representing the larger universe, then the inside is the smaller universe, or in other words the self. Further, this “universe” is characterized by and conforms to such natural laws such as “unity” and “structure.” Therefore, by achieving a direct connection between your self and the greater universe, you can obtain the latter’s strength, that is to say, you are then able to take advantage of the divine power that is at the root of the universe. Thus, the circle with the point inside also represents the circular movement of aikido.

While it may be that aikido is a part of Japanese culture specifically, I think there is also something more universal about it, something that allows it to resonate with people from anywhere, regardless of country or culture. In other words, O-Sensei taught that aikido movements are one with the fundamental essence of the universe, and what makes these movements possible is the sincerity and purity which are inherent in human beings and should be shared by people everywhere. This purity of spirit is often addressed within the context of Japanese religion and art, but in such cases, it can only be explained in more complex and difficult terms than we find in the simple, elegant “circle with a point inside.” We can glance at it and be able to come to the understanding of its essence.

This is the first in a two-part interview. You can read the second part here.

Translated by Derek Steel

Add comment