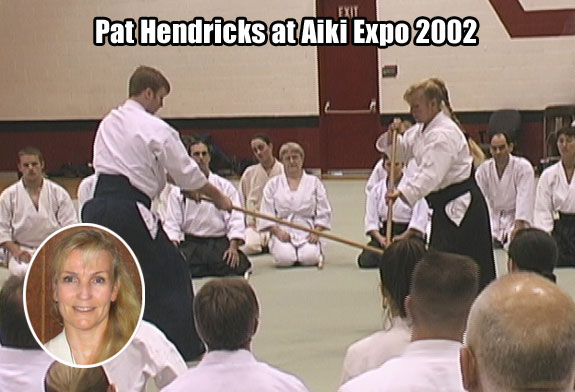

Ikuko Kimura: How are you enjoying the Expo?

Pat Hendricks: This is more than I ever expected, there is so much talent here, not just the teachers, who are amazing, but so many people of a really high caliber. I don’t think I’ve ever seen any event in my whole martial arts career that equals this.

I hear you trained very hard to prepare yourself for the demonstration?

Yes, my three students, who are all exceptional in their own right, and I have done demonstrations together in other martial arts events, so at first I thought, “We have our standard demo, we can just change it a little bit.” But then I felt this event was so important that I wanted to put more time in and help make it as special as it deserved to be.

How many students did you bring?

Eight uchideshi (live-in students) from my dojo came, and two former students who have now become teachers, plus ten direct students of mine and another four or five from various regions.

How many students do you have?

I have about sixty adults and fifty or sixty children, at my dojo, so over a hundred all together.

Do you teach every day?

Yes, I do. My philosophy, that I got from observing Saito Sensei, is that no matter how high-ranked I get or how advanced I am, it’s really important for me to do as many classes as I can. So when I am at the dojo and not traveling, I teach all the classes. That’s just what I do. I teach the kid’s classes because I feel that inspires them.

When did you originally start aikido?

I started in the summer of 1974 in a small college in Monterey, California where Mary Heiny was teaching. Soon after enrolling I found Stanley Pranin’s dojo, which was also in Monterey, so I started going there. I drove about an hour each way three times a week to get to the dojo.

How old were you then?

I was eighteen when I started aikido in June and I turned nineteen in September, so when I entered Stanley’s dojo in the fall, I was nineteen.

Stanley said he was very proud of you.

Oh, I’ve always had unbelievable support from him. He was my first teacher and I learned so much from him. I did three times a week with him, and then a Saturday women’s aikido class with Danielle Smith. At some point I moved into Stanley’s dojo and became a sort of informal uchideshi, and trained in all the classes.

Around 1977, Stanley went to Japan. We were up at Oakland training with Bruce Klickstein at the time. Bruce had already been to Iwama once and he was getting ready to leave for a longer stay there.

Bruce, a couple of the senior students and Stanley, in other words everybody I felt close to was going to Iwama. So I just decided, “Well, I’m going to go too. It must be a neat place.” I had done a year or a year and a half of university and decided to take a year off and go to Japan. I stayed over a year, which was longer than I expected. This was Fall 1977, when there were few foreigners or uchideshi. The training was very severe and traditional. It is still traditional in Iwama, but not so many people are going through what I had to go through.

At that time it was easy for any uchideshi to have personal contact with Saito Sensei and his family. Bruce Klickstein and I were the only uchideshi for most of that year.

No Japanese uchideshi?

No, there were people that came for a month or two, but the only long-term uchideshi before us was Shigemi Inagaki. He was Saito Sensei’s first long-term uchideshi. He taught at the morning class where mostly just the three of us trained. It was a very hard training, very intense. They were third or fourth dan and I had just become shodan. I learned a lot, including all my weapons training, in those circumstances.

My philosophy, that I got from observing Saito Sensei, is that no matter how high-ranked I get or how advanced I am, it’s really important for me to do as many classes as I can. So when I am at the dojo and not traveling, I teach all the classes. That’s just what I do. I teach the kid’s classes because I feel that inspires them.

Being in Iwama for over a year and training in that way must be worth a couple of years or more elsewhere?

Absolutely. We saw Saito Sensei all the time and worked with him all day long.

Did he go abroad at that time?

During my stay, he took his first international trip, to Sweden, but it was unusual for him to travel. He didn’t travel anything like he did in the past ten or fifteen years. After that trip to Europe, he didn’t go anywhere for a long time. He was at the dojo a lot; he would have lunch with us and even cook for us. It was a wonderful time in that sense, but the training was very, very severe and a lot of people got injured. I took my shodan test soon after entering the dojo and within two weeks I got my arm broken. But in those days you didn’t stop, so I had the bones set by an old blind doctor, Mr. Tachikawa, who was very famous in Iwama. When they brought me in I saw this old blind man just feeling around with his hands and I thought, “I am in trouble now.” But, he was amazing! He was a genuine healer! He took me on as a special project and used all kinds of needles and things to get my arm working again.

How many weeks later?

Within two or three weeks, the arm was set and I was training with one arm. Full recovery took about five weeks. It was winter so it was slow to heal. I did experience full recovery, though, and it was fine after that. That was just the way things were done at that time. You would get a bloody nose one night or get something twisted, and it was par for the course. I got many injuries, but I think that was about the time when Saito Sensei decided to really make an effort to make the training safer. Bruce was there and Mr. Inagaki as well. Bruce is a great sempai and a big brother to me. His aikido was awesome.

Why did you become interested in aikido in the first place?

In high school, I saw a lot of Bruce Lee movies and I was just drawn naturally to the martial arts.

Why aikido, then?

To be honest, it was a coincidence. I wanted to do martial arts, and aikido was what was offered at the time; but from the moment I did my first class I knew it was for me. Everything fit, the movements, the philosophy, the way people taught, everything! I don’t know if I would have stuck with another art, but aikido just suited me from the very beginning.

Have you tried any other martial arts?

Over the years, I’ve had a lot of martial arts friends and have done many camps like this although they were on a smaller scale. At a lot of camps you just take whatever classes are being offered. People tend to ask you to play around, so I have experimented with a lot of different martial arts, but aikido has been one consistent thread through my whole life.

So you stayed in Iwama more than a year, and then went back to America?

I went back to America for nearly eight years then returned to Iwama for a number of months, and I continued going back frequently as a short-term uchideshi until 1988 when I decided to become a long-term uchideshi again, for the last time. I have made fifteen or sixteen visits to Iwama all together, but that was my fifth or sixth. I had already started my own dojo back in 1984, and I deliberately decided to leave it, turned it over to a friend and went back to Japan, where I stayed for about 18 months.

If you added up all the time you have spent in Iwama, how long would it be?

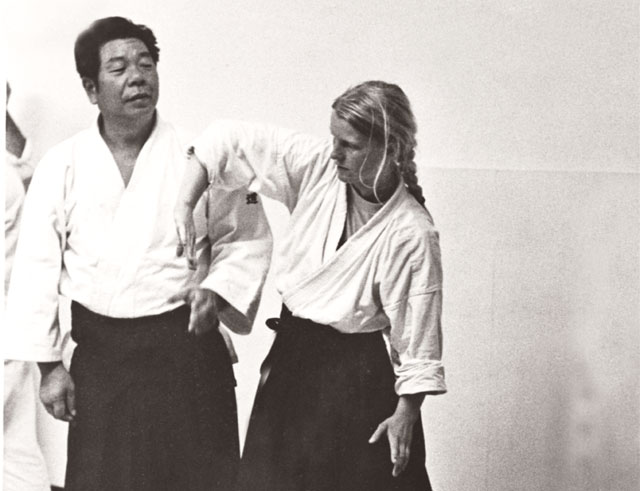

I think it would add up to around six years. In 1988 I was experienced enough for a lot of opportunities to come to me. It is a kind of funny story. On one occasion Saito Sensei was being interviewed by the famous Japanese magazine, Wushu. He did a few things with me but mainly used the male uchideshi.

Then everybody dressed for lunch, except me as I was serving tea, as I normally did, still wearing my keikogi. Saito Sensei said to this man, who I guess was the editor, “Well, I guess I can demonstrate with her even though she is a girl,” and he started demonstrating, and just didn’t stop.

I took my shodan test soon after entering the dojo and within two weeks I got my arm broken. But in those days you didn’t stop, so I had the bones set by an old blind doctor, Mr. Tachikawa, who was very famous in Iwama. When they brought me in I saw this old blind man just feeling around with his hands and I thought, “I am in trouble now.” But, he was amazing! He was a genuine healer! He took me on as a special project and used all kinds of needles and things to get my arm working again.

It was in the middle of summer and really, really hot. He just went on and on for about forty minutes. I thought to myself, “I will never see any one of these pictures, they will never be in the magazine, because I am a woman.” Well, apparently, those were the only pictures they chose! When Saito Sensei received the magazine, he quietly placed it on the shomen (altar) and didn’t show it to anybody, and I felt he was disappointed. But then he started getting calls from all over Japan telling him that the article looked good because he used a foreign woman as his uke. This completely changed Saito Sensei’s thinking. After that, he was so much easier about using a woman as uke and expecting that kind of response from others.

So, you went back to Iwama in 1988, and then?

During that time a lot of things happened. I had done some demonstrations with Saito Sensei back in 1976, but it was in the period 1988/89, when I was fourth dan, that Saito Sensei really took me on as a professional uke and otomo (traveling companion). He had never done that with a woman before, and not with many foreigners either.

Things really changed and I feel like I pioneered a lot of changes for women. I was once again a long-term uchideshi and I was taking part in demonstrations. I was in the friendship demonstrations, too, and I did a number of different trips with Saito Sensei.

That article in Wushu changed everything because he got such positive feedback from everyone. Also, the whole weapons system evolved during that time. Saito Sensei really lifted it to another level. He started thinking about issuing traditional certification in the form of hand-written transmission scrolls for weapons techniques. And the ken-tai-jo techniques were codified while I was there. Saito Sensei also added a lot of variations to the weapons techniques, so it was a really exciting time, and I was able to be a part of that.

Before any of the scrolls were given out, Saito Sensei wrote me out a menkyo kaiden (advanced proficiency certificate) that basically said, “I have taught you the entire repertoire of ken-jo.” I didn’t really understand what he was doing and I thought he was giving me the first weapons scroll, which I would have been honored to have. However, he had me write it in English and he went over my writing with a calligraphy pen in addition to the Japanese version he wrote. While he was doing this, someone said, “Do you realize what this is?” I said, “Well, this is a certificate.” They said, “No, this is a menkyo kaiden. You are getting the only menkyo kaiden that we know of.” I don’t know if this is true, there might have been somebody else that got one but, anyway, it was a great honor. He gave it to me privately because, even then, the Japanese people would not have been happy to see me get it. I was fine with that.

We did a bunch of demonstrations and I traveled a lot with Saito Sensei. This period set me up as Saito Sensei’s uke. We shot pictures for the Takemusu Aik book series, and traveled all over the world doing demonstrations. Saito Sensei had the courage to take me on in a way that had not been done before.

He was taking you around because you are so good, not because you are woman or for any other reason.

Yes, I realize that, but it hadn’t happened before, so for the first time other women could look at me and say, “Hey, we can do this!” I played the role for them. I know that Saito Sensei didn’t treat me any differently just because I was a woman. He judged me from a neutral place. That’s what I loved about him. He truly believed that women as well as men should go as far as they possibly can.

You proved it! How many people could come back to Iwama and stay that long! Living in Japan is very difficult, too.

Yes, it’s very difficult.

I know that Saito Sensei didn’t treat me any differently just because I was a woman. He judged me from a neutral place. That’s what I loved about him.

So you did it, and what you did changed Saito Sensei’s mind.

A lot of people have gone to Iwama and lived outside the dojo as sotodeshi for periods of years, but it’s very unusual to be a foreign uchideshi to stay for a long time. I think he recognized that.

So you have been teaching since 1984?

Well, I was teaching here and there back in 1978, but just at tiny workshops in dojos. In 1984 I opened my own dojo in San Leandro, so now it has been eighteen years.

Maybe now it is not so rare to see a woman running a dojo but I think at that time it was rare even in the States, wasn’t it?

Yes, it was very rare. It just didn’t happen.

At this Aiki Expo I saw many women teachers doing demonstrations. It’s still rare to see a woman teacher in Japan, but not so in the States these days. Even so, back in 1984, for you to have a dojo must have been highly unusual?

San Leandro, where I still am, was a rather conservative town. I went through a hard time in the beginning. People would come in and ask who the instructor was, and when they found out it was a woman, they would turn around and leave. But gradually it changed and now it’s not a problem at all. Some people even specifically seek out a woman instructor these days.

Things really changed and I feel like I pioneered a lot of changes for women. I was once again a long-term uchideshi and I was taking part in demonstrations. I was in the friendship demonstrations, too, and I did a number of different trips with Saito Sensei.

But you had already been through that with Saito Sensei and he changed?

Yes, so I knew that it was possible. I just persisted and finally people recognized me. Since 1989, a kind of regular national and international seminar circuit has evolved for me. My dojo is growing, and we have more uchideshi than I can handle! But it’s wonderful. This seminar has been so easy for me because I can just go and teach or train and I have somebody next to me all the time offering me tea, or whatever. My dojo is basically run by my students, they all do different things and I am quite happy with the way things are. I keep on getting opportunities to teach alongside really high-caliber teachers. I am very honored, and I feel like opportunities keep on opening up for me. Magazine articles, radio interviews and some television appearances have happened for me, so I feel good about that, too. Things are definitely going in a positive direction.

As a teacher, what do you emphasize most?

I tell you what my philosophy is, after all these years of teaching: When someone walks into the dojo I look at them and ask myself in what way this human being needs to evolve? I am just an instrument, I am not going to do anything to them, and I am not going to make them into anything. I just do my spiritual work. I do my meditation, and “empty out” so that energy can move through me into my teaching. All my teaching is spontaneous. It just comes through my connection with the universe, so when I make corrections or whatever I do so on the inspiration of the moment. My training is to continue to be able to be that kind of teacher, without being too attached to the results. And yet I see the results. I find a way to take each different individual to their full potential just by channeling what they need. It works! I find I can produce really high-level students.

You are a great teacher.

Thank you. I love teaching. That is my responsibility. I started teaching in some sense of the word when I was maybe twenty-two or twenty-three, then I started my dojo before I was thirty. I was always a relatively young teacher compared to the others. For whatever reason, I have been chosen to be a pioneer. You know, doing a lot of the first things for women and being able to break the barriers down so that others do not have to do it. It seems to just come naturally to me. I am not a radical feminist. I just love aikido and I love seeing women progress, just as I love seeing men progress as well. I don’t have any special agenda.

You are a pioneer because of what you have done, without trying to be one. It’s like the Aiki Expo. If you focus on getting people together to make money, maybe not so many people would get together like this. Stanley had a vision and the vision is important.

Yes, very much so. And people respond to that. Most people respond to passion. If you have passion, people can sense it.

In conclusion, could you give us some more impressions of Aiki Expo?

The Expo is much more profound than I expected. There are truly groundbreaking relationships happening here. It’s bringing different styles and different teachers together. We are exchanging information with each other and finding out how similar our philosophies are. Stanley did an excellent job in picking people that get along with each other easily. I feel that a lot of barriers are being broken here: the Japanese/American barrier, the male/female barrier — having me in the line-up with all those high-ranking men is such an inspiration to women — and also barriers between the cultures.

Everybody is training together and realizing that the different styles, aikido or aikijujutsu or whatever, are just “forms” to help them get to the core. We are just using these forms as vehicles, so we shouldn’t take them too seriously.

I want to say one more thing, to men as well as women. When I had my son three years ago I thought, “Oh, aikido will stop and my life will stop, I will just take care of the child.” But just the opposite has happened. He has traveled all over the world with me and it has got to the point where his energy is so important for the seminar. He has a subtle influence on things. Even here his presence has been a special thing. I took him to Iwama and he was unbelievable. He was like an uchideshi! So, for me, being a mother is a part of the martial art path we are on all the time. If you were not on it your child could die. Sometimes you see and hear about unspeakable things that your child could be exposed to. As a parent you also have to open your arms and welcome new things.

I was always a relatively young teacher compared to the others. For whatever reason, I have been chosen to be a pioneer. You know, doing a lot of the first things for women and being able to break the barriers down so that others do not have to do it. It seems to just come naturally to me. I am not a radical feminist. I just love aikido and I love seeing women progress, just as I love seeing men progress as well. I don’t have any special agenda.

I really encourage women and men too to have a family. It integrates your life. You can still do everything you want to do. It just brings everything into balance and all the pieces fit together.

Thank you very much.

This interview was conducted by Japanese editor Ikuko Kimura at the May 2002 Aiki Expo 2002 in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Contact for Pat Hendricks: Aikido of San Leandro

Add comment