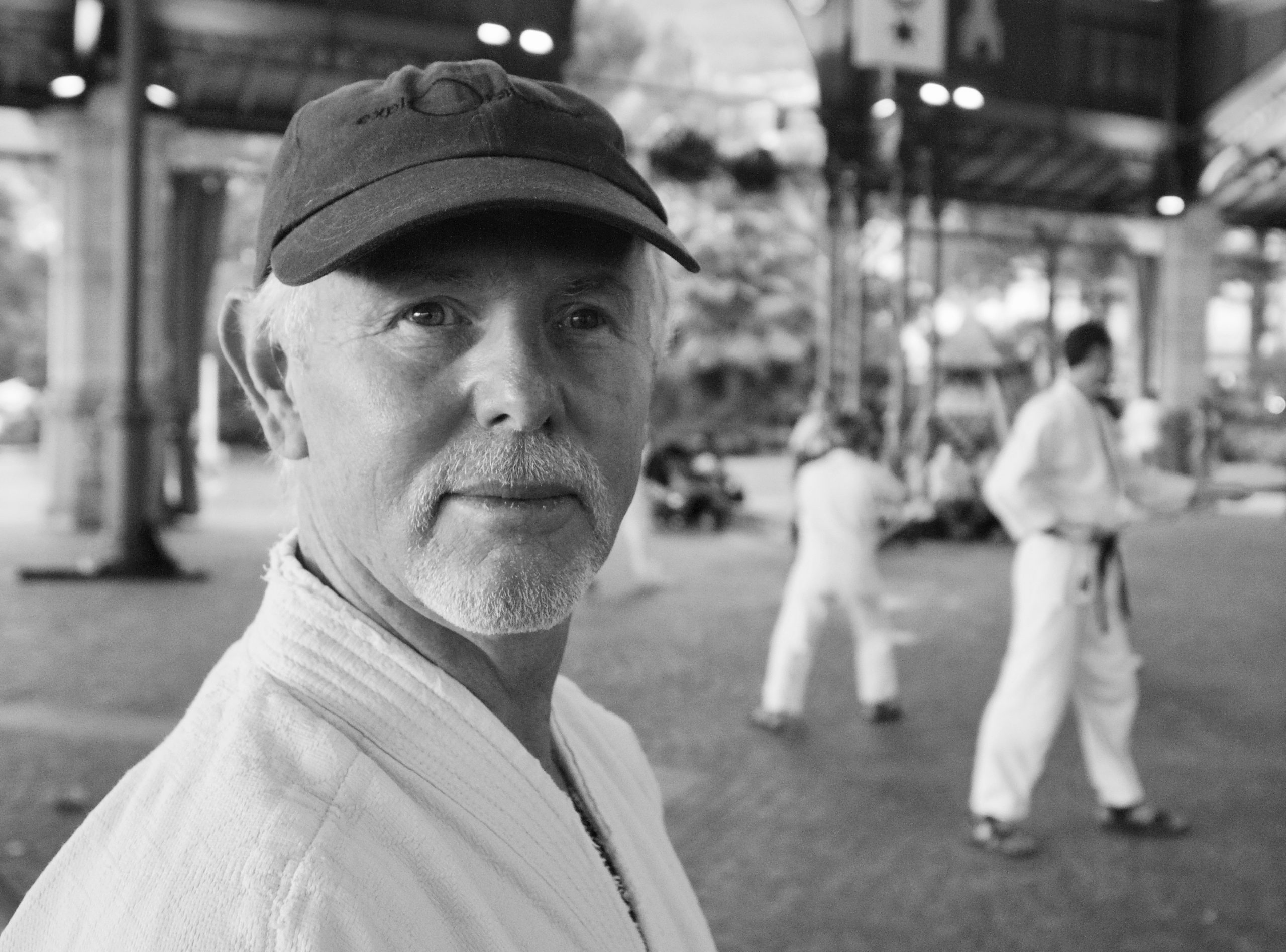

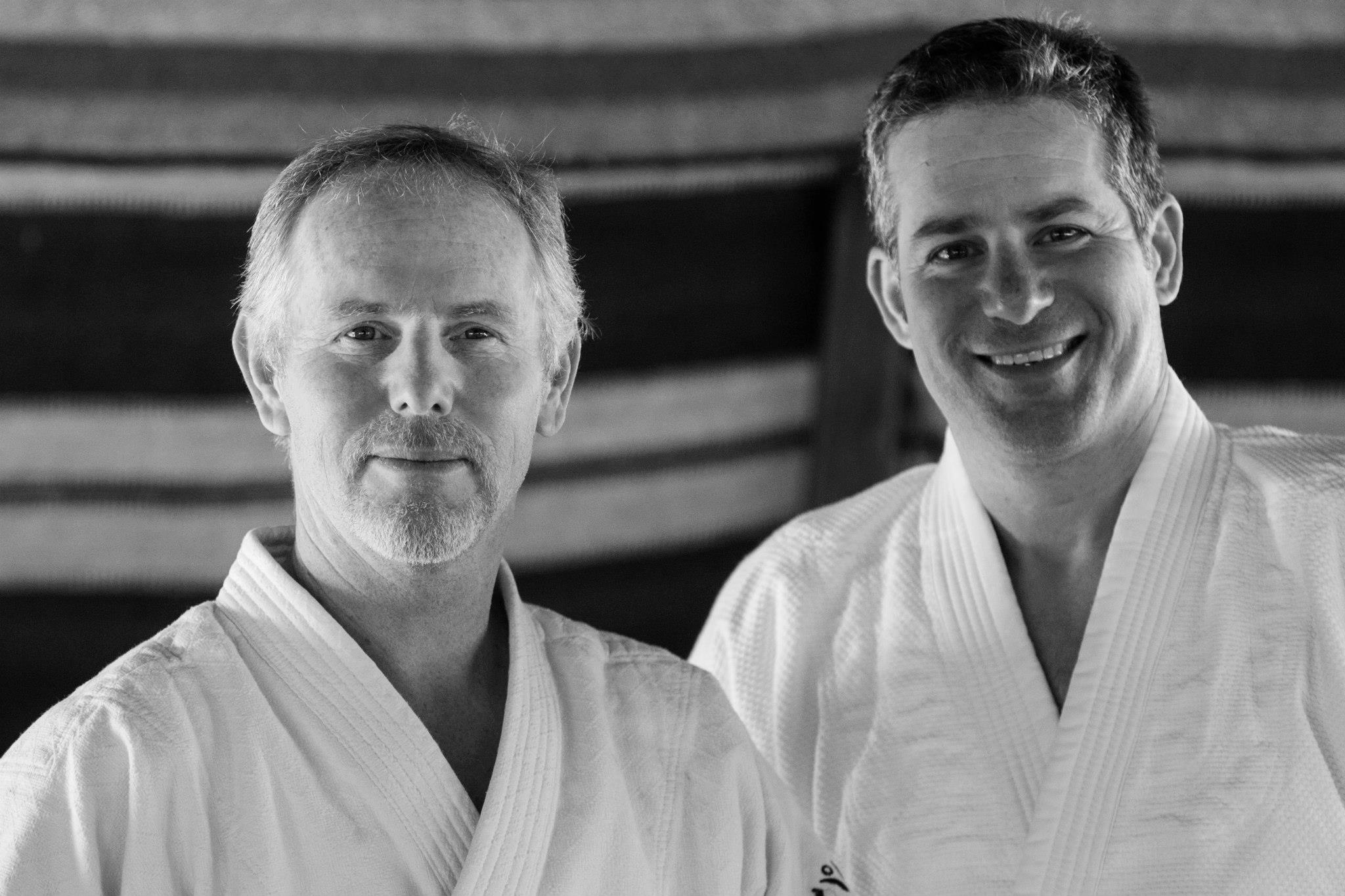

This editorial has been contributed to Aikido Journal by Patrick Cassidy Sensei. Patrick started Aikido in 1983 as a university student and soon after, left for Asia. He studied for a total of 7 years in Japan (primarily with Morihiro Saito), and 3 years in India, Nepal and Tibet. During this period, Patrick devoted his time to Aikido, Yoga, Meditation and Japanese Tea Ceremony. After returning to California, he became Dojo-cho (Executive Director) of Aikido of Fresno and continued his training with Peter Ralston, Robert Nadeau Shihan and Richard Moon Sensei. Seven years later, he left the U.S., moved to Switzerland, and founded Aikido Montreux. He is currently ranked 6th dan Aikikai and is founder and director of the EAC, Evolutionary Aikido Community. Patrick also leads the Conscious Practice Institute, which offers conflict resolution programs for psychiatric hospital caregivers.

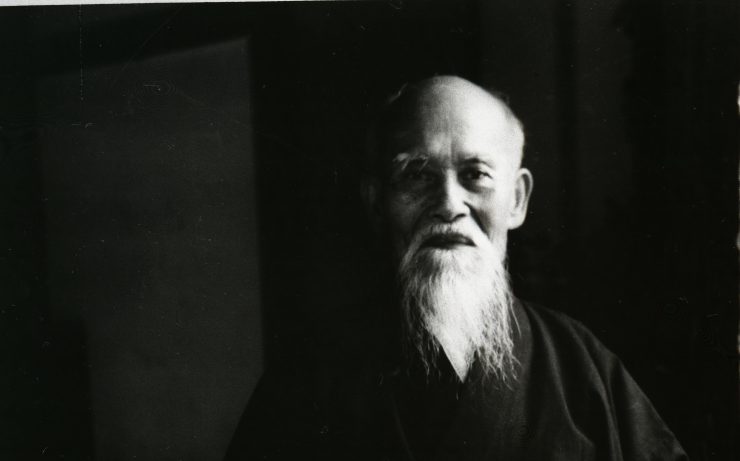

Aikido has been going through a number of transitions over the last few decades, as a practice and as a community. When I began Aikido, almost 40 years ago, the community was still full of 1st generation teachers. Teachers who had been students of the founder, were in their prime, and leading global communities themselves. Senseis Tohei, Chiba, Nishio, Yamaguchi, Shioda, Kobayashi, Hikitsuchi, and my first sensei, Morihiro Saito, among many others were leading the charge and bringing Aikido to the Western world with a passion. It was the great migration of Aikido into the public eye and it had a huge impact on human culture.

We were introduced to a physical practice that employed “ki”, which spoke of blending with the attack of the aggressor and finding a way to be in harmony with the world. Aikido’s message was welcomed by many. It was a golden time for Aikido and many Western teachers grew in popularity during this period. One aspect of the world of Aikido was the diverse physical interpretations that were offered by the various students of O’Sensei. From Shioda to Tohei, from Yamaguchi to Saito, each sensei seemed to offer a different perspective on the art. This was both a strength of the art as well as a potential weakness. It engendered both an appreciation of differing perspectives and stimulated attempts to define who is teaching the true Aikido and who is not. This became evident as the 1st generation teachers became more popular and more vocal about what they felt was important and valuable in the art.

In the last 30 years, Aikido had started another transition. We began to lose many of the 1st generation teachers and the world of Aikido was starting to be led by 2nd generation and 3rdgeneration teachers – instructors who trained with students of the founder or a student of those students. Aikido was becoming more independent from the original voice of O’Sensei and it started taking on a life of its own. This has obviously led to more diverse interpretations while stimulating attempts to codify Aikido according to different sources. It was as if each teacher felt that their interpretation was the “correct” one and what was being taught in other dojos was less pure. From my perspective, this led to many disagreements in the Aikido community and rather than appreciating the differences, Aikido communities started to become more insular.

“For many, Aikido is what keeps us in balance with life, centered under pressure, and empowered with a sense of being with our lives. Aikido is like an internal compass that keeps us on track while we respond to the challenges we face. “

At this time, we also had the introduction of the UFC, the combat sport that welcomed anyone to test their skills in the “octagon.” It was a big wake up call for many and it introduced the art of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, and eventually the practice of mixed martial arts into the world. This has created another form of debate- which martial art is the most effective in this context? The martial arts became training for gladiator-like combat in the ring and each was trying to show its effectiveness in this new-found arena. Of course, Aikido was drawn into this debate as well.

With Aikido being a practice of meeting aggression with an aim towards harmony, it did not seem to translate itself well into this new world of MMA. Although the techniques of Aikido can be lethal in nature, the art is practiced without competition, and explored collaboratively between training partners. The perspective of Aikido as professed by the founder, was to “end the discord in one’s mind/heart” and to bring the world into “one family.” Aikido struggled with the question of functionality within the world of MMA as the intention of the art of Aikido did not seem suited for this gladiator-like approach.

On top of this, Aikido still existed in a traditional hierarchy. This hierarchy set up to appreciate not only the skill of practitioners, but their experience and time committed to the art. It followed a Japanese cultural bias of a sempai/kohai relationship that attempts to honor each person in their role based on their history, experience and skill. This is based on a positive sentiment but can fuel a lack of transparency and dialogue within the community as junior students do not question the judgement of the senior students in this type of hierarchy. It can lead teachers to hide themselves within a role of being higher ranked and therefore more “advanced” and not available to questions or challenging opinions. This type of structure does not function within the MMA world of testing of one’s skills in the arena and letting the best man or woman win. Bringing the art of Aikido into this domain and attempting to measure its worth as a fighting art was never really going to be successful. Of course, certain techniques of Aikido can be applied to the MMA context and the principles of the art certainly are functional in this realm. But the art of Aikido attempts to address conflict at the physical level through resolution rather than destruction or competition. This vision of Aikido concerning conflict is fundamental to the art and translating that vision into the competitive combat arena is contradictory to its nature.

Yet bringing the question of how Aikido does function in real time with a committed attacker is a valuable exploration. From this question, the effectiveness of Aikido in the physical domain has been debated. For the most part, this debate has been stimulating as it brings us into addressing the physical practice for its merits. But the art is bigger than just studying how we response to physical attack. Aikido researches how we respond to conflict in all of its manifestations. It is a systemic and integral art.

“It was as if each teacher felt that their interpretation was the “correct” one and what was being taught in other dojos was less pure. From my perspective, this led to many disagreements in the Aikido community and rather than appreciating the differences, Aikido communities started to become more insular.”

This last year with the covid crisis and all of the challenges that have arisen from it, has been a huge blow to our world health, culture and economy. Many people have lost jobs, businesses, family members, their wellbeing and emotional stability. It also hit the Aikido community with a terrible impact. Long established dojos have had to close their doors for lack of financial support due to lockdowns and the regulations that were implemented due to the virus. With to the loss of the chance to train together indoors, many teachers moved their practices outside using the weapons training of Aikido as way to continue. Other teachers moved to online venues as a way to stay connected and keep the practice alive.

We have seen an explosion of classes held online, with everything from practicing basic body movements to exploring the relationship of Aikido with Meditation. There have even been a number of seminars held online and the International Aikido Federation itself has featured different senseis from around the world leading classes. It has been a radical shift in how we share and practice the art. But even more importantly, it has brought the discussion of “What is Aikido?”, to a greater audience.

As the founder put it, Aikido is not found in the dojo but exists where you are at all times, in all places. For many, this had seemed like a nice sentiment, but not truly understandable. Yet now with the Covid crisis, we are faced with the question of finding Aikido outside of the dojo. If the dojo is no longer available for us, can we continue to walk the path of Aikido? Can we still practice the art? What is Aikido, if there is no longer any dojo to train in?

“Aikido is a life art, integral and systemic in nature. It looks to bring the individual into greater balance without destroying the system that individual lives in.”

This has been a challenging endeavor. I personally have seen many instructors and practitioners struggle to come to terms with their work and their path as their dojos have had to close. I have seen many teachers ask the question, “Who am I as a person, if I can no longer teach Aikido, if I am no longer a sensei?” This is a wake-up call for those of us that have identified so strongly with being an Aikido sensei or sempai. We can feel lost without that role. But I believe most of us can see that being attached to the identity of being a teacher or senior student is fundamentally a limitation. Being attached to our role in Aikido, keeps us from truly embracing the art with that important “beginners mind,” shoshin. It is humbling to see how much our personal confidence can take a hit when we lose that role of being an Aikido teacher/senior, even for a short time.

And yet there have been other leaders in our community who have found ways to innovate during the pandemic. Leading online classes, seminars, creating instructional videos, sharing perspectives in online panel discussions, and offering new ways for the Aikido community to progress while being away from the dojo. Creating a “virtual” dojo. This new way of communicating and being in community has been impressive as it has been born almost overnight. Zoom, YouTube, and Facebook have become the new method of sharing the art that we love. This developmental step is inspiring and has in many ways brought us closer together as a world community.

And with all of that happening, there has been another movement within the Aikido community: a movement towards a deepening of the practice on the personal level. A valuable reassessment of our personal relationship to the art. With no dojo, no partner, just our relationship to the moment, to life, how do walk our path? What does it mean to practice Aikido as a solo path? For some it means a turn towards a greater connection with meditation and the spiritual viewpoints of the art, others have found ways to deepen the relationship to movement and the intelligence of the body, and for some, they have found a deeper connection with nature and the elements in the natural world.

But with all these developments, the most valuable and yet perhaps least understood new perspective from this period of Covid quarantine has been a discovery of something very simple: Aikido has been keeping us sane. For many, Aikido is what keeps us in balance with life, centered under pressure, and empowered with a sense of being with our lives. Aikido is like an internal compass that keeps us on track while we respond to the challenges we face. Throughout these last months, many have shared with me the simple realization, “Aikido is what keeps me sane.”

“I have seen many teachers ask the question, “Who am I as a person, if I can no longer teach Aikido, if I am no longer a sensei?” This is a wake-up call for those of us that have identified so strongly with being an Aikido sensei or sempai. We can feel lost without that role. But I believe most of us can see that being attached to the identity of being a teacher or senior student is fundamentally a limitation.”

Most Aikidoka agree that the value of the art is broader and deeper than just looking at the question of self-defense on the streets, or effectiveness in a MMA context. Aikido offers not only a method to respond to physical aggression but also a way of meeting the challenges of life. It offers a different operating system for processing the threats we collectively face. This new operating system offers a way to respond and be with the threat, a way to thrive in relationship with that threat, a way to address that threat so that we may find a solution that includes the whole. Aikido is a life art, integral and systemic in nature. It looks to bring the individual into greater balance without destroying the system that individual lives in. Aikido recognizes that fundamental truth that we have been reminded of with the Covid crisis, that there are some ukes you cannot over power, that we need to work together as a system to finds solutions, and that I as an individual am not “victorious” until I am at peace with my world.

Aikido offers a new way to be with the world. Neither being victim nor aggressor, but somehow finding a way to be in accordance with the radical changes that life brings. And this ability to respond to radical change, is an ability that is sorely needed right now in the world.

So how do we convey this message to those who are really struggling with trying to keep control of their daily lives and feeling like each change is a threat to their survival? Can Aikido help people find their center in the midst of an ever-changing context? What if Aikido could be a way for people to learn how to navigate change rather than resist it? Would that be of value? To find one’s capacity to be creative under pressure, rather than reactive? Can Aikido offer these skills? What if the practice of Aikido included this perspective of learning to manage change? Perhaps this could be one the roles that Aikido can play in the new world we all face.

For us as Aikido teachers, before we offer Aikido as art for navigating life, obviously we need to be able to live that art. To be able to walk our talk. That perhaps is the next step we can consider for the future of our community.

In the end, I will leave you with a short anecdote from my life in Japan. During the winter of 1987, I believe, I and a good friend who lived also in Iwama, Lewis de Quiros, decided to join Shoji Nishio Sensei’s Winter Gasshuku which was held near Tokyo. After we arrived, it was soon quite evident how skillful Nishio Sensei was as an Aikidoka and an overall martial artist. Nishio Sensei was not only an 8th dan in Aikido, but a 6th dan in Judo, 5th dan in Karate, 7th dan in Iaido, and Jodo. He had blended his total experience into a seamless expression of Aikido. The training was very different than what we had encountered in Iwama yet we felt soon at home in the practice and enjoyed what was shared. During the Saturday night party of the camp, we both found ourselves across the table from Nishio Sensei with few of his seniors in attendance. The party was warm and we felt very welcomed, and Nishio Sensei was a gracious host. He stopped at one point in the evening and turned to us and asked us if we had any questions that we would like to ask. I turned to Lewis, and then back to Nishio Sensei and said yes. I began by thanking him for the gasshuku so far and the wonderful experience I was having. And then I asked my question. Without any disrespect to Nishio Sensei, I wanted to know his opinion about something our teacher would often say…Saito Sensei often would say that he is doing the Aikido of O’Sensei. I wanted to know what Nishio Sensei thought of that statement. I know that to say the least, this was potentially a very rude question to ask and may have even appeared as an insult or attack on Nishio Sensei’s teachings. But in all honesty, I trusted him and it felt safe to ask this very delicate question at that intimate moment during a pause in the party. To Nishio Sensei’s credit, he didn’t react or seemed put off by the question at all but responded with a deep sincerity. “Saito Sensei is doing what O’Sensei was doing in Iwama, and yet O’Sensei was in a constant state of evolution. Evolving both his Aikido and himself as a person. That is what I am doing. In that way you could say we both are doing O’Sensei’s Aikido”.

This encounter with Nishio Sensei stayed with me and I was humbled by it. He shared his perspective and convictions without needing to defend them. He shared that Aikido had something more than tradition or technique as its foundation, but something that could support the practitioner to evolve.

Where are we going as an Aikido Community? I don’t know, but I do think we need to consider what it means to evolve…

thanks so much – Nishio sensei showed some excellent aikido there.

“The essence of Aikido is the cultivation of the spirit of reconciliation”

if the atomic bomb hinted that conflict was not a sustainable path, how does the present political climate indicate the increasing need for aikido

and/or more so, the essential principles of ai & kokyu, love and harmony.

looks to me the only path to ‘create a beautiful world.’ but, what do i know

first, aikido is not an art, so it cannot ‘evolve’–it is misogi, if it can so function, that’s a lot.

nice, thanks….

Dear Richard, I agree, Nishio Sensei demonstrated a rare quality of welcoming a different perspective with no resistance and clearly staying centered and true to his path… In finding a sustainable path in relationship to resolving conflict, it seems that the perspective of Aikido is an essential element in whatever process we engage in. Learning to recognise that we are both an individual and a collective simultaneously and that we need to discover a path that includes the well being of both sides of our experience. For me that is the essence of what we are practising…

Yes let allow Aikido be a polishing tool to become a better human, challenging without violence the current global human challenge to transcend to a human kind spirited with Aiki….for the benefit of all.

Thank you Sensei Wilco for polishing me as one of your many studends to become a more compassionate person and do some good

Dear Wilko Sensei, Thank you for your words, yes I resonate with your message…allowing Aikido to be a practice for us to become more human, strong without violence, capable of meeting the global challenges we all face.

Dear Patrick,

Thank you for your very thoughtful essay, I appreciate it very much. I believe that at this time of global and personal transition, the ability to shift, adjust, adapt and change is a survival tool that in the long run could prove to have been an integral aspect of our training in the arts, as well as in life. Ultimately life influences our art much as the arts influence our lives.

The capacity to go with the flow with harmony and without resistance is crucial in both spheres of our existence. Indeed, learning to coexist with all aspects of both life and death may be our true mission as we navigate our path on this pale blue dot known as Earth.

Thanks again for sharing your experiences and raising such important issues to ponder.

Dr. Carl Totton, PsyD

Dear Carl,

Your response touches me. You have pointed to the essence of what I value in this art. The depth of Aikido includes all of the ways we face challenge and adversity…and can provide a context for discovering a path that supports the evolution of ourselves and the natural world we are a part of. With gratitude!

Thank you for the article. The Nishio Sensei anecdote is spot on – I trained in Shioda Sensei’s Yoshinkan lineage and it is accurate to say it was taught to us as O’sensei taught aikido to Shioda – this was the pre-war aiki-budo period, so naturally it appears to be different. Now I train in a lineage that traces back to Tohei Sensei. Again it is taught to us as O’sensei taught aikido to Tohei Sensei in the early years of the Aikikai lineage. Now in 2020, we still are doing O’sensei’s aikido. The critical understanding, in my view, is that each aikidoka has their own aikido, and debating who’s aikido is “O’sensei’s aikido” misses the point entirely. It is the core principles found in the art that make up aikido. Ueshiba Sensei’s aikido evolved over time, as did his understanding of budo and the physical representation thereof, as he walked his path. It is natural and in aiki that all of us do the same.

Best regards and keep the flame alive

Ryan Clarke

Dear Ryan,

Thank you for sharing, it does seem to be a confusing aspect to our art…the differing interpretations of Aikido that all of the Senseis present can be a point of contention, but as I have continued to train, I have come to appreciate the differences and recognise the value of multiple perspectives of the art.

With you on the path,

Patrick

First, thank you very much for a thoughtful and humble perspective Patrick.

Listening to a Ram Dass talk that my wife shared with me this morning a little phrase jumped out, “I’ve noticed that as people become more conscious they are less manipulative of the universe in order to bring about what they think they need.” I think this is a sense of our practice that you and I and many others share. As Tohei Sensei would say, “Extend positive ki” Or Nishio Sensei would say, “Aikido is about giving, not taking.” At a shodo workshop many years ago with Kaz Tanahashi (hosted by the late Ron Rubin and his lovely wife Susan Perry) Tanahashi Sensei talked about stillness. Sometimes our mind can become scrambled with questions of what to do. But we can remember that stillness always remains a possibility.

I think when people seek out aikido that deep down they are seeking something like stillness. Beginning and ending each class in seiza we wrap our practice in this sense of stillness. Then we strive to carry that sense of stillness into our actions. With stillness we can be aware and receptive, we can breathe, feel, listen, learn, absorb and grow. As the hostility, noise and chaos of this age wane there will naturally emerge a longing to return to that stillness. In the meantime we can nurture our own stillness, preserving the way for future generations without feeling compelled to push the universe for what we think we need right now. The winter of difficult times nourishes us in its own way by helping us toward greater clarity and a deeper sense of purpose.

I think your question to Nishio Sensei was the kind of thing he would appreciate because it gave him an opportunity to say that the aikido he was pursuing was both respectful of tradition and convention while not being entirely bound by it. He also never felt compelled to push his ideas on others, but rather invited them to try. I think this is a good perspective to have as we forge our way into the future.

Dear Philip,

Thank you for sharing your perspective. I agree on that people are drawn by the stillness that can be found in Aikido, and at the same time the capacity to be free while being under pressure. That sense of being with rather than against and recognising that the stillness found within can not be diminished by any threat or force from without. For me that discovery offers the person to respond without being antagonistic to the other… Creativity arising from that stillness you are referring to…

In stillness and creativity,

Patrick

Very comprehensive and illuminating. Thank you. I particularly enjoyed your daring question to Nishio Sensei, and his elegant response.

R. Kravetz

Aikido in Fredericksburg (Virginia)

Dear Robert,

Yes the question I posed to Nishio Sensei was an inspiring moment…

With thanks,

Patrick

“But…i do think we need to consider what it means to evolve…” beautiful article.

You got it! A question with limitless possibilities!

Patrick

Bravo!

A beautifully crafted piece, Patrick. Thank you. I think all new students should read it and hopefully so will everyone else who practices aikido.

What I particularly like is the wonderful dichotomy between sharing the same purpose but giving room for individuality as to how we we achieve it.

It’s also a wonderful reminder of O Sensei’s vision for aikido.

Dear Quentin,

Thank you for your words. I too am seeing the beauty in the appreciation of the differing interpretations of Aikido while sharing the fundamental vision of the art.

Can we stay open to exploring the differences while staying grounded in what keeps us a community? This is a challenge that I feel is important for us to navigate in the future…

In peace,

Patrick

A thoughtful article with some interesting insights. A pleasant surprise actually.

In my eyes aikido is a personal journey for everyone who practices. Every person’s capacity for understanding themselves and their relationship with the world defines their aikido ability. Every person’s aikido is their own. A Sensei guides and does not teach. Experience does not prevent others from making mistakes.

It is for these reasons that I would prefer not define myself as an aikido teacher…. my aikido contributes to a bigger life.

Dear Michael,

I agree very much on the nature of Aikido being a personal journey. And that the ability of an individual’s aikido will be framed by the relationship they have with themselves and the world. As for the role of the Sensei…I feel sometimes that I am just reminding people of what they already know…

In spirit,

Patrick

Excellent article, Sensei Cassidy, thanks for sharing your thoughts and wisdom on how Aikido can help us go through this difficult period of our lives.

Hi

Just read this

Haven’t trained in years

I thought I might again

I thought, thank God you’re still alive

I thought wow, how far we have come

I thought, I want to see if my aikido experience is different because I have been on a spiritual journey

I thought about being young and strong with you in Iwama dojo

I think I have a picture of you somewhere.

I am grateful for your spiritual insight

I wish you well

Luna