In this illuminating interview, Bernie Lau, a seasoned Aikido practitioner with over six decades of experience, shares his remarkable journey in the art. From his chance encounter with Koichi Tohei Sensei on a Hawaiian beach to his insights on applying Aikido principles in real-life situations as a police officer, Bernie provides a unique perspective on how Aikido became an integral part of his life.

Josh Gold: You were one of the very early American Aikido practitioners. Tell us how you first discovered the art.

Bernie Lau: It all began with a chance encounter at Hapuna Beach one year. I was with the Boy Scouts, conducting swimming lessons for various troops from around the Big Island of Hawaii. We’d rotate between Kona, Hanukkah, and Waimea. One afternoon, while I was strolling along Hapuna Beach, I spotted a group of young Japanese men with an older figure in the center. Curiosity led me over to observe. The sensei, Koichi Tohei, was being attacked by the younger members, and suddenly they were airborne or on the sand. I was astounded. I’d never witnessed anything like it. Eventually, Tohei Sensei noticed me and called me over. He asked, “What’s your name?” I replied, “I’m Bernie Lau from Hilo.” He then said, “I want you to strike me here.” I gave it my best shot, aiming for his face. In a flash, I found myself seated on the sand, completely baffled. He reassured everyone, “He’s fine.” The younger students, all teenagers, chuckled. There I was, a foreigner in their midst, and Tohei Sensei was effortlessly putting me on the ground. I attempted a few more times, each time ending up bewildered. Now, of course, I know he was applying kotegaeshi on me. Tohei Sensei said, “You’re from Hilo, right?” “Yes.” “Next week, I’ll be in Hilo teaching Aikido at Tea Garden, Lili’uokalani Park. You should come, be my guest.” About a week later, I arrived at the Tea House at the appointed time. I knocked, the shoji slid open, revealing a Japanese man with crutches who asked, “What do you want?” I stammered, and then Tohei Sensei recognized me. “Come in. I remember you.” I entered the Tea House, which was being used as a dojo. He introduced me to different people, Takashi Nonaka Sensei, Nagaoka Sensei, and two others. There were just five of them in total, Tohei Sensei included. Then he said, “Come, I’ll show you a lock.” I complied, and Tohei Sensei applied sankyo on me.

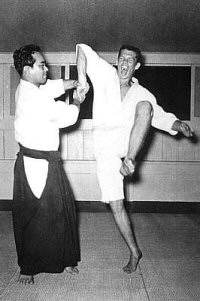

Yes. He instructed, “I’ll apply, and you jump.” He wanted a good picture. So, he applied, and I jumped. My friend, Michael, captured the infamous moment. That was my initial introduction to Aikido – Tohei Sensei applying sankyo on me. I’m not sure if anyone else remembers their first lock in Aikido, but for me, it was sankyo, and it’s etched in my memory.

How old were you then?

I was 15 years old, back in 1955. At the time, it was mainly Japanese practitioners with a few local boys training in Aikido. I take pride in being possibly the first gaijin, the first non-Japanese person, in Hawaii and the United States in general to learn Aikido. The art didn’t arrive in the continental United States until much later.

How did your Aikido practice progress from there?

Tohei Sensei began teaching at a venue we called the Cow Palace. It was a massive auditorium, with a section cordoned off for Aikido training. We’d gather there twice a week in the evenings. This routine continued for about a month and a half. Then Tohei Sensei relocated to another island. Despite his absence, I kept up with my Aikido training, maintaining a twice-weekly schedule. Tohei Sensei returned in 1958, three years after I first met him in 1955. When he visited the Big Island in Hilo, he’d instruct at the Cow Palace. One day, he held kyu tests for everyone. I, too, was tested and received a third kyu certificate in 1958. It’s been quite a long time, and I still have it. I’m pleased to have kept it all these years. Later on, Tohei Sensei visited a place that was 40 miles from Hilo. I had the privilege of riding in the backseat with Nonaka Sensei, Tohei Sensei, and one other Japanese individual. I felt quite awed, thinking, “Here I am, riding with all these esteemed people from Japan.” It was a profound experience for me, a young 15-year-old, being introduced to this foreign world of Aikido. There, Tohei Sensei would teach, and then the students would engage in the usual training session.

And how did your Aikido journey progress through the 1960s?

I graduated from Hilo High in 1960 and enlisted in the US Navy. After my basic training in San Diego, California, I underwent electrical schooling. Following that, I applied for voluntary submarine duty and was assigned to the USS Bluegill in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It was a dream come true to serve on a submarine. Later, I pursued my goal of becoming a diver, both hardhat and scuba, also based in the submarine base. During port stops, I’d head up to Kaimuki, where Hawaii Aikikai, the main dojo, was located. I’d train there two or three times a week. Sometimes on early Sunday mornings, I’d engage in misogi practice with Shuji Mikami. While in port, I’d often go there several nights a week for basic Aikido training. Yukiso Yamamoto was the chief instructor at the time.

“He reassured everyone, “He’s fine.” The younger students, all teenagers, chuckled. There I was, a foreigner in their midst, and Tohei Sensei was effortlessly putting me on the ground. I attempted a few more times, each time ending up bewildered.”

When did you first visit Japan?

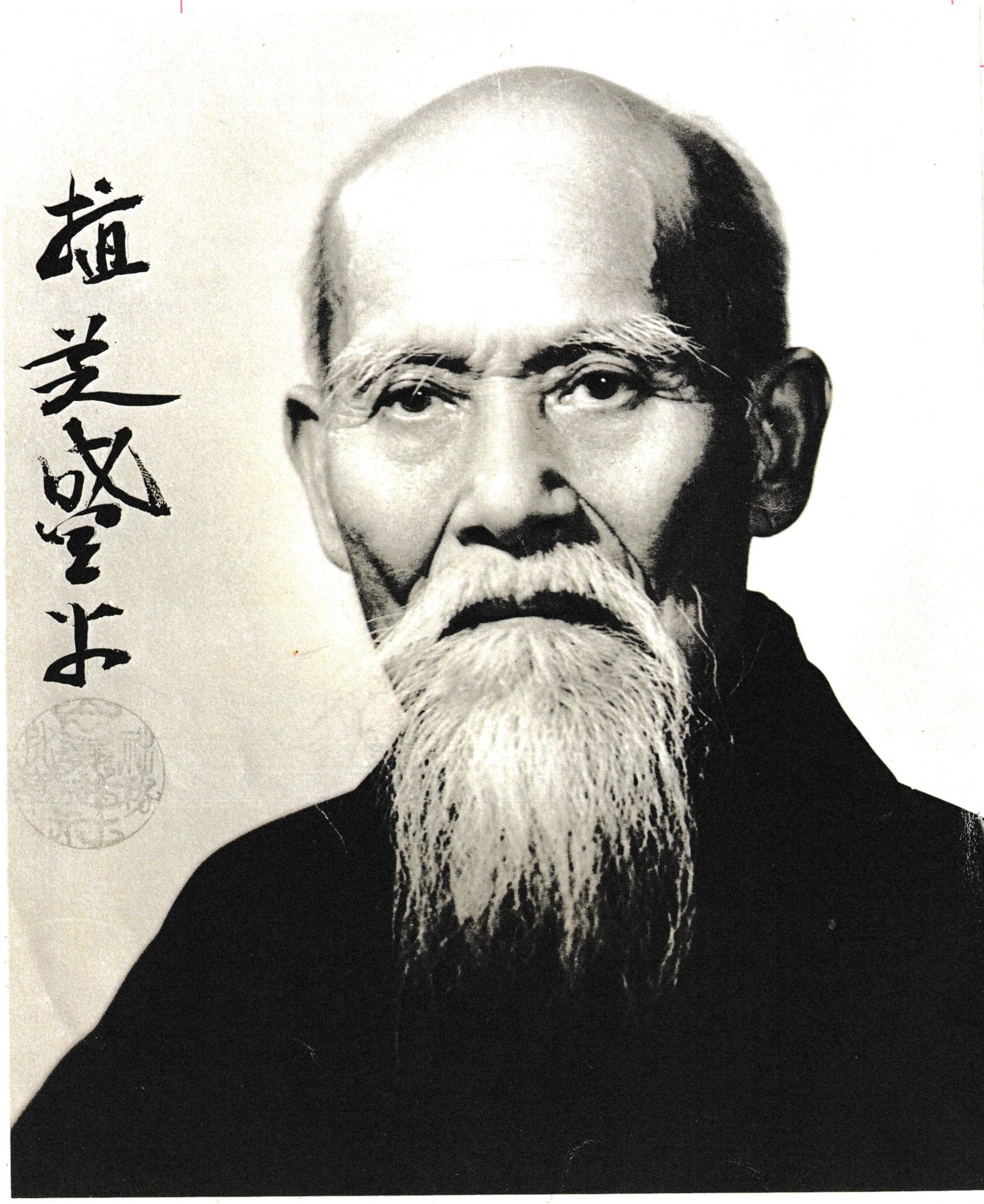

With the submarine, we made a stop in Yokosuka, Japan. However, our stay wasn’t long enough for me to journey to Tokyo. So, in either 1964 or 1966, I made a personal trip to Japan with the aim of meeting O-Sensei and Virginia Mayhew, who was residing near the Hombu Dojo and trained there daily. We reconnected as I knew her from Hawaii. She kindly offered to introduce me to O-Sensei. A few days later, she took me to his residence, where a few other Japanese individuals kept an eye on me. They wanted to ensure I was respectful. I met O-Sensei, who was seated behind his desk, smiling. Yamamoto Sensei had given me a bottle of whiskey to present to O-Sensei, which I did. He was very grateful. I also had a portrait of O-Sensei concealed under my shirt, which I pulled out. I asked, “O-Sensei, would you kindly sign it?”, apologizing for my audacity, of course, all in translation. He was more than happy to do so. This portrait was taken in Hawaii, and I had tracked down the studio where it was photographed. I purchased it and kept it with me for years. I didn’t have a secure place for it, so Reverend Shokai Kanai, whom I’d met in Seattle years ago, offered to buy it. He keeps it safe in his wonderful dojo in Granite Falls, Washington. Kanai Sensei is now the proud custodian of this remarkable portrait, originally signed by O-Sensei. I don’t believe O-Sensei signed many portraits, so it’s quite a treasure to possess. It’s a wonderful piece of history.

You knew Tohei Sensei for decades. What do you think was his greatest talent, and what do you think was an area of weakness for him?

Tohei Sensei always wore a smile. When he taught, he was joyful and often half-joking. He exuded a charisma that made it impossible not to like him. I distinctly remember his forearms – oh, how I wished mine were like that. I even tried exercises for bulkier forearms but ended up with carpal tunnel syndrome. My wife, Nancy, at the time, told me, “Bernie, that’s just how he’s built. You could try all your life, but you won’t have forearms like Tohei Sensei, and that’s perfectly fine.” I learned that the hard way. Over the years, Tohei Sensei would stay in Hawaii for about six months. There was a room at the back of the dojo specifically for him. Every evening, members of the dojo would take him out for dinner, drinks, and merriment.

I think his biggest flaw was when he decided to part ways with the Hombu Dojo. Everything was going smoothly until Tohei Sensei determined to follow his own path and teach Aikido according to his own vision. But that meant leaving Hombu because they wouldn’t permit him to teach what he wanted. Once he left, a choice had to be made in Hawaii: you had to either choose the Hombu Dojo with O-Sensei or choose Tohei Sensei. I was with the Aikikai at that time, and I don’t care much for politics. This was around 1973-74 when the split occurred. I simply left the Aikikai and started teaching a small group independently. I think that was his biggest flaw, or mistake, but people make such decisions for personal reasons. That’s just how life goes.

I’ve read his resignation letter, and I heard the way he announced it was quite dramatic. It was at a dinner party with Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba.

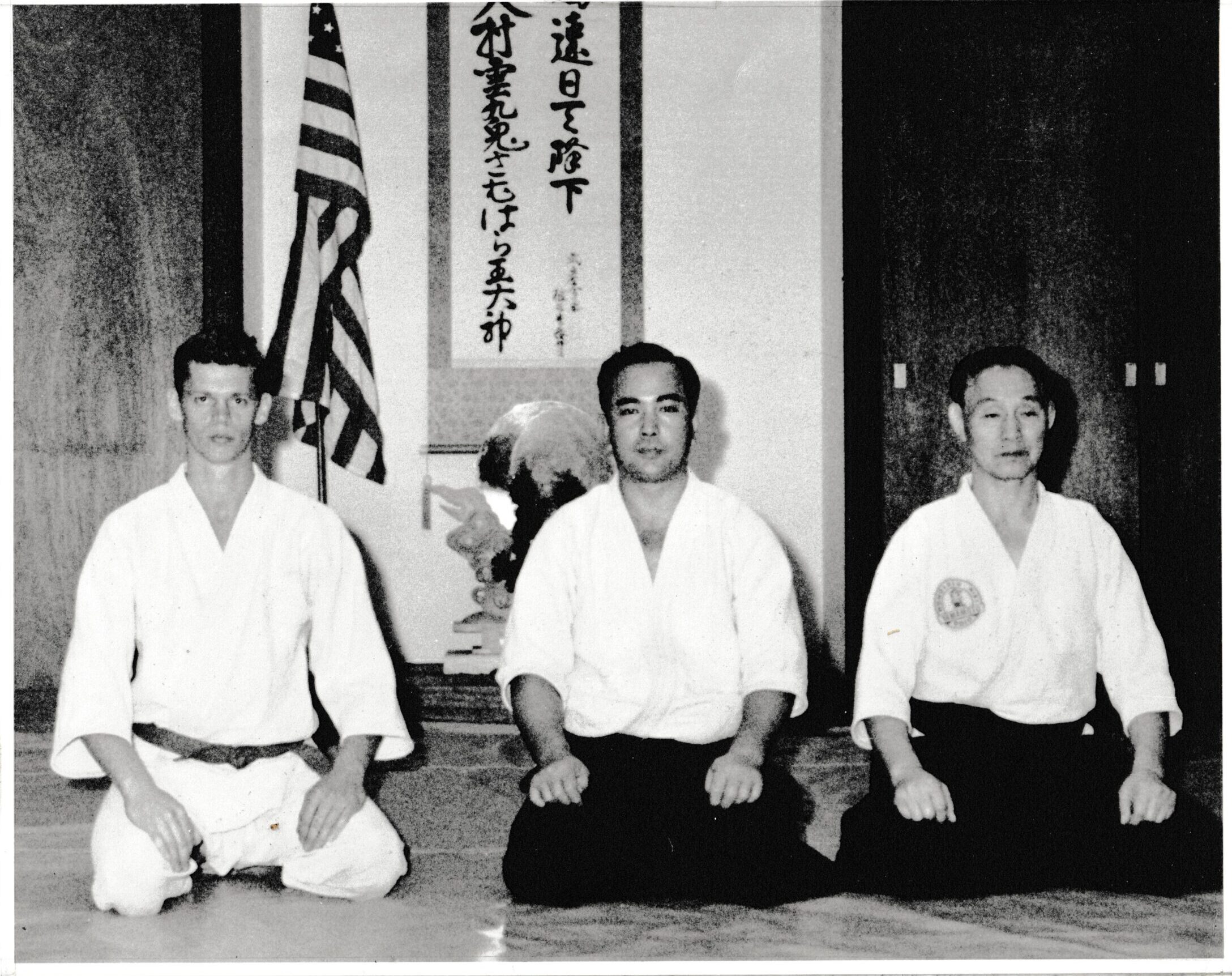

Yes. I have a copy of the notice that was sent out to all the dojos announcing his departure. I was fortunate to keep a copy, and Kanjin Cederman Sensei has it now. But before that happened, Tohei Sensei would occasionally visit Seattle. I think it was two or three times. I met him and accompanied him to a couple of seminars he conducted. One of them was at the University of Washington. I have a photo of Yoshihiko Hirata Sensei, Tohei Sensei, and myself that I’ll provide copies of. I’ll pass on everything I have for your records.

Stanley Pranin told me that you were instrumental in his research into Daito-ryu and the history of Aikido, is that correct?

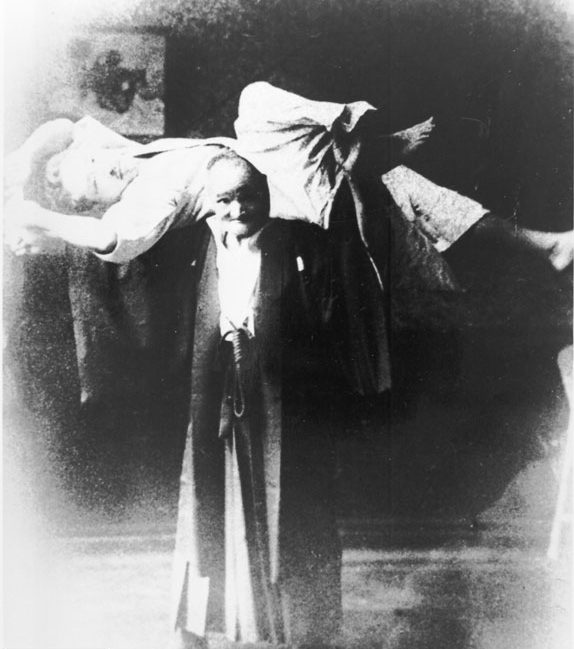

That’s right. When I was training, the name Takeda would occasionally come up. We’d wonder about the history of Aikido, and the word was always that O-Sensei developed Aikido from scratch, that he was the sole creator. Yet, I kept hearing about Sokaku Takeda Sensei. So, I did my own research and discovered that in Hokkaido, Sokaku Takeda’s son was head of the dojo. So, I decided to write him a letter. In the early 1970s, there was no internet, so you sent letters. I knew Reverend Kanai from the Nichiren Shu Buddhist Temple in Chinatown, so I asked him to translate the letter for Takeda Sensei. I wanted to inquire about the history of Aikido. Kanai Sensei agreed, but he thought Tokimune Takeda Sensei might not respond. I assured him he would. We sent the letter in Japanese to the main dojo for Takeda Sensei in Hokkaido. A few weeks later, I received a response. I had introduced myself as a police detective in Seattle, shared a bit about my Aikido history, and requested any photographs or writings that showed Morihei Ueshiba receiving lessons from Takeda Sensei. I received about a dozen photographs and a booklet mentioning O-Sensei, Morihei Ueshiba, and the fees he was supposed to charge students. Everything I received, I sent to Stanley Pranin, whom I knew well. He eventually used them for Aiki News (later renamed Aikido Journal). The famous photograph of Sokaku Takeda with someone on his shoulders came from his son. His son mailed it to me, and it’s now a widely recognized image.

How did you first connect with Stanley?

Let’s see, that could have been about 40 or 45 years ago in the early 1970s. Time flies. It might have been one of the Aikido seminars that Stan would organize, probably once a year. Eventually, I think Stan met Takeda’s son, Tokimune, and interviewed him. Stanley did a wonderful job of interviewing most of the old-timer senseis, which is great because we now have records.

“Everything was going smoothly until Tohei Sensei determined to follow his own path and teach Aikido according to his own vision. But that meant leaving Hombu because they wouldn’t permit him to teach what he wanted. Once he left, a choice had to be made in Hawaii: you had to either choose the Hombu Dojo with O-Sensei or choose Tohei Sensei.”

Stanley also came to Seattle two or three times and stayed with me at my home, along with a few of his assistants from Aiki News. One night, Stanley brought a 16-millimeter film and showed it to me and a few other people in Seattle connected to Aikido. We watched it in the basement of the Seattle Nichiren Shu Buddhist Temple. Reverend Kanai kindly offered the use of our facilities to show the movie. That night, we saw some of the older Aikido films, and it was pretty wonderful, quite impressive.

For many years, you were a police detective. Can you talk a little bit about if and how you used Aikido in your police career?

I joined the force in 1970. For the first two or three years, I was a uniformed officer walking a beat and driving a patrol car. There was one incident on the waterfront in Seattle. I was in plainclothes but noticed a larger, unruly guy, sort of a lumberjack type. I was a rookie cop and did not handle things well. I approached him, and he responded with hostility. I said, “You’re under arrest.” Prior to this, I had used sankyo on people I arrested, maybe a dozen times. After the arrest, I’d apply sankyo, with my partner on the other side holding the suspect’s arm. It was easy to apply sankyo, and most of the time, it worked. If not, the suspect would go down, and we’d handcuff him while he was on the ground.

But with this particular individual, the lumberjack, I attempted the lock, and he countered skillfully. There was no way I could control him, and it ended with me kicking him in the groin a few times. Unfortunately, that didn’t slow him down; it just made him angrier. Eventually, I called for backup, and you could hear sirens all over Seattle, officers rushing to help. They saw that I had been assaulted, and they responded quite aggressively in dealing with him. I felt terrible because why hadn’t Aikido worked? I was baffled and felt awful because the man was seriously injured. I’m not one to hurt anybody. Some policemen don’t mind, but I prefer not to. The concept of Aikido is not to harm the individual if possible.

That experience sparked my interest in how to effectively use Aikido in police work. I reached out to Nonaka Sensei in Hawaii and a few others, including Yoshioka Sensei, asking how Aikido could be applied in law enforcement. Both of them were uncertain and said, “I don’t know. I’m not a policeman.” Even when I asked Nonaka Sensei in person, he said he wasn’t sure since he wasn’t a police officer. From there, I embarked on a quest to figure out how to apply Aikido effectively in police work.

In my backyard, I built a dojo on a small terrace. It was a 20-tatami dojo. I’m not a construction expert, but I read a lot of books and managed to build a 20-tatami dojo for training law enforcement officers. We had a group of about 12 officers who came to train three times a week. We began with sankyo, and I’d always say, “Okay, you guys, if you’ve made an arrest, how did it go? If it didn’t go well, what techniques did you use to subdue the suspect?” It was a process of research, because I believed that your training informs your research and further development or fine-tuning of the technique that you’ll likely use when apprehending an individual.

I’d say that about 90% of the time, sankyo proved to be highly effective. However, I later realized that with sankyo, you have to use both hands to apply it the way it’s taught. Now, if I’m attacked by someone else and I let go with one hand, the individual can get away. They can squirm out of it, which isn’t ideal. Then I met Professor Wally Jay, and we became close friends. Wally is also from Hawaii, and we spent an afternoon together fine-tuning sankyo. Instead of using the whole hand, he emphasized using the little finger. We fine-tuned the technique, so now, if I have one hand free and apply it, that usually stops them. It works quite well.

That seemed to work well. Wally Jay and I became good friends, and I’d visit him in Alameda, California almost every other year. Our birthdays are both in June, so I’d go and celebrate his birthday in Chinatown with a great Chinese lunch, along with his wife, Bernice. It was quite an interesting adventure, all because of Aikido.

You mentioned that Tohei Sensei would occasionally do demonstrations at police departments, but they weren’t interested.

I think when Tohei Sensei came to the US and Hawaii in 1953, he would go to O’ahu and do demonstrations at places like the Hilo Police Department. The officers would watch and think, “Okay, it looks good,” but like myself, they didn’t really know how to apply Aikido. One thing is, you can’t kotegaeshi or use ikkyo to flip someone on the street. The individual, not knowing how to take ukemi, would get seriously hurt. With myself, I found that 90% of the time, if you can apply sankyo, that will assist you in making your arrest. Nowadays, law enforcement has changed. They usually have guns drawn and say, “Get on the ground” to the young suspects.

You’ve been through all these different roles and stages in your life. How do you think Aikido has influenced you or helped you get through some of those stages or challenging moments in your life?

Well, I think it helped me maintain a calm and relaxed mind, like when I was walking a beat. It also increased my awareness. I noticed everything that was happening around me. Instead of tunnel vision or just focusing on one thing, I’d be able to see everything that was going on. Later on, I worked undercover in narcotics for about ten years. There was an incident where I went to a guy’s door, he opened it with a shotgun. Without thinking, I just blocked the shotgun. It went off, and that’s in one of the books I wrote, Dance With the Devil, about my life as an undercover narc.

Like I said, because we also trained in the dojo, we trained with real knives and real guns. We even used real shotguns. Some would ask, “Why are you doing that, Bernie? It’s dangerous.” I’d say, “Well, I’ve never been attacked by a wooden or a rubber knife, or a phony gun. It’s all for real.” Sometimes, I’d have someone reach out to me, putting a shotgun in my face. They’d say, “Oh, don’t do that, move it.” I’d respond, “What are you going to tell the suspect if that happens to you? This is real training. You’ve got to learn fear control. You need to realize that, ‘Okay, you’ve got a shotgun in your face. You’re better. We’ve practiced this a lot; it’s second nature.’ Are you going to bark, ‘Okay, you guys, wait a few seconds before I pull the trigger?’ No, you’ve got to move. Don’t think, just move.” Then take action, almost like kotegaeshi, and get hold of the weapon. It might turn into a tug of war, but we trained for situations like that. It helped me remain calm. The training with real firearms, unloaded of course, helped not just me but also other officers on the street.

Another thing, before I became an officer, I was on a submarine. We were out during the Cuban Missile Crisis for almost a month, 40 days and 40 nights, without a shower. It was an old diesel-electric submarine, not like the nuclear ones where you can take a shower and do your laundry. We were the real “pig boats,” as they called us. But we were off Russia during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and on the submarine, you could be 300 feet below the surface, just above the test depths. You could also go to periscope depth, which is maybe 30 or 40 feet under, with just the periscope sticking up. At that depth, you’d raise the periscope and then lower it back down several seconds later.

Well, there was one time when the periscope wouldn’t come down. I don’t know what was wrong, but you can’t go deep with the periscope sticking up like that. The seals are what keep the water out when the periscope is down. I might not have been a good electrician on the submarine, but I was always available for something kind of out of the ordinary that had dangers connected with it. I would have to go down the periscope well, feet first. They helped me in, and then once I was in, I’d have my hands up. Then, I mean it was tight, but the walls were greased. So slowly they lowered me down 20 feet. Talk about claustrophobic! You’re in a tube, it’s dark, you can’t move. You’re going down feet first. If something happened, how would they get me back up? But just being in that space, how I conquered that is, I put myself in the dojo and I started a small chant. I just saw myself in a dojo and then worked on my breathing slowly. My psyche, my whole mind was in the dojo setting; it wasn’t in the tube. Somehow, I survived. But let me tell you, it was an experience I wouldn’t want to do again.

“One thing is, you can’t kotegaeshi or use ikkyo to flip someone on the street. The individual, not knowing how to take ukemi, would get seriously hurt. With myself, I found that 90% of the time, if you can apply sankyo, that will assist you in making your arrest.”

How long were you in that tube?

Maybe 15 minutes. They said, “Go down and see what you can find.” At the bottom of the periscope, I moved things around. I don’t know what I did. But eventually, they brought me back up, pulling the chain up. Then the captain tried it, and it worked. Because otherwise, if we were caught off Russia and they picked us up, if you’ve got an American submarine out there during the Cuban Missile Crisis, who knows what might have happened.

As you look back on those 65 years of Aikido, what do you think about it now as an art form, as a daily practice?

It’s part of my life. I don’t think, “Oh, this is Aikido.” When you do something for so long, it’s muscle memory, it’s your mind, it’s everything is included. My whole life I get out of bed, I’m centered. It’s all, Aikido became part of me. It’s a way of life. Do no harm, be aware of everything around you. Things like that, it’s just part of my life. I don’t know where I would be if I hadn’t had that wonderful experience of meeting Tohei Sensei at Hapuna beach one day, just like that. Aikido is a wonderful part of my life. Without Aikido, I wouldn’t be the person I am now.

When you talk about centeredness, in your experience as a police officer, did you find that the officers who didn’t have martial arts training background had that same centeredness and awareness?

Well, I think the officers who had martial arts training definitely had an advantage. They already had a foundation in things like awareness, centeredness, and mental calmness. They were more prepared to handle high-pressure situations. But that’s not to say that officers without that background couldn’t develop those skills through their daily work. It just might take longer, and they might have to go through more trial and error. It’s like anything else, the more you train, the better you become. Traditional martial arts provide a structured way to develop those skills, but it’s not the only way. It’s just a tool.

I believe that Aikido principles can be applied in many aspects of life, not just in law enforcement. It’s about being present, aware, and centered. It’s about responding to situations with calmness and clarity, rather than reacting with panic or aggression. These are qualities that can benefit anyone, whether they’re a police officer, a teacher, a parent, or anyone else.

I heard you were awarded the rank of godan from the Aikikai in 2021.

Oh, yes. It was quite a surprise. Someone said, “Bernie, I think there’s something coming for you from Japan.” It was my 5th dan certificate in Aikido. I got shodan and nidan from O-Sensei and I got sandan and yondan from his son, Doshu Kisshomaru. Then, from the grandson, Moriteru Ueshiba, I got my fifth dan. Before all of that, I received my third kyu from Tohei Sensei in 1958, so I’ve got the whole line. That’s something, I’m blessed to have that whole lineage.

Once I made fourth dan, I said, “I’m not seeking any other dan because I got my ranking from O-Sensei, his son, and Tohei Sensei. Who else can give it to me?” It wouldn’t feel the same. That’s the way I looked at it. Another thing, in the late 1970s, these younger shihans would come from Japan. They’d do a seminar in Seattle, walk around and ask, “Oh, what rank are you?” “Yondan.” They’d give me a funny look. I said, ” Signed from O-Sensei.” They hadn’t even met O-Sensei. I’ve moved on.

But to have a fifth dan, it was a surprise, and I was very happy. I’m very pleased and it was quite a shock in a wonderful way.

Lisa Tomoleoni Sensei helped you get that?

Yes, and I must thank her.

Do you have any parting words that you’d like to share with the Aikido community?

Well, I’m back. I’m a member again of the Aikikai, so I’m back in the family, which makes me very happy. When Tohei Sensei went his own path due to negative politics, I just quit. But now, I’m happy to be back, connected with the Aikikai. It’s a good feeling.

All I can say is train. Aikido is a wonderful art. If you’re looking for actual self-defense, there are other arts. If you’re at a certain level, I always recommend you take some other art – Karate or another striking art. Sometimes, you need more than Aikido if you’re thinking in self-defense terms. Aikido is wonderful but there’s no resistance – that’s how Aikido is practiced.

When I go to Chile, I teach Aikijujutsu. Aikijujutsu just means more locking. I believe in realism. I enjoy training Aikido – it’s a wonderful art but in police work, you have to focus on actually going out and try to arrest people who don’t take ukemi. You have to see what happens; how they resist. You have to supplement your aikido with other training and research – you have to add something else to it. There’s nothing wrong with Aikido but know why you train Aikido. Do no harm, but if the situation calls, you better be ready.

Thank you for this amazing conversation.

Great interview! I met and trained with Bernie many years ago in Dayton Ohio when he visited a local dojo. He and I both trained Yamate Ryu Aikijutsu under Lovret Sensei in the 80s. Bernie is a great guy and I was impressed and lucky to have been able to experience his teachings.

Wonderful interview. Bernie had the rare and unique opportunity to have met and trained with Tohei Sensei as a young adult.

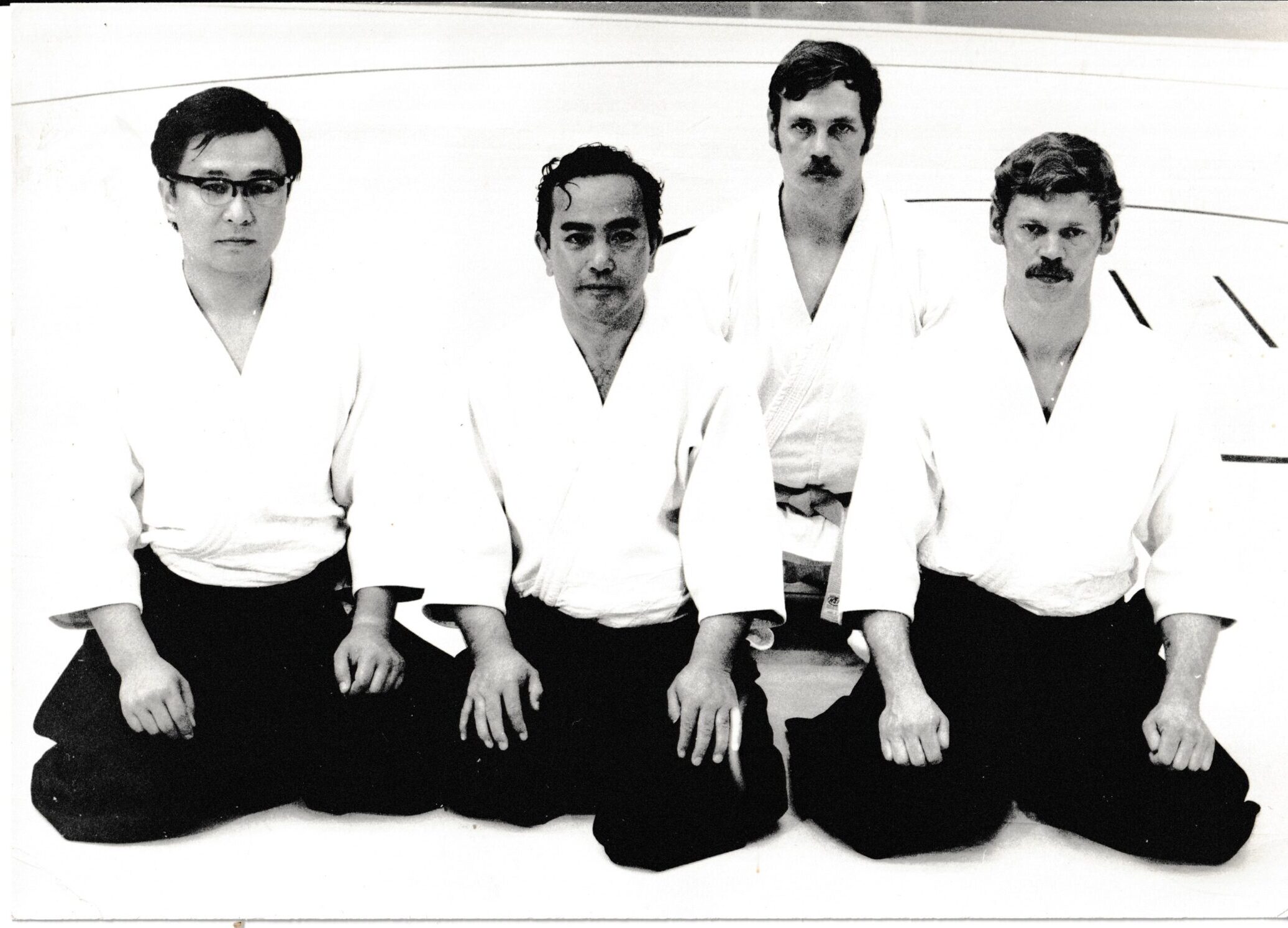

Please note that in the photo taken at the Hawaii Aiki Kai it is Yukiso Yamamoto seated on the right. Also, please note that part of the scroll in the tokonoma has been cropped out, but

Right side begins with. 勝速日

Left side begins with 天村

This scroll, to the best of my knowledge, is MIA.

Great inside. Thank you very much. Don’t know Bernie Lau in person but remember seeing some old videos (Bernie Lau Productions) from the small dojo over and over. There is a sequence where he is walking with some other person in the garden which I think to remember correctly was Wally Jay. Again: great story, great inside.

Wonderful article. Thanks. I’m in Gainesville, FL. Maybe it was about 15 years ago, John Kerry came to talk, maybe he was running for president at the time. He had a question and answer session and a big kid started harassing him. A female campus cop tried to quite him down and attempted the control him. No effect. They had to get a “moose” cop to come in and manhandle him out. Later the campus police chief couldn’t get him quiet, so she tassed him. That’s where the “Don’t tase me bro!” came from. We started playing with what could have been done to control him. We started with a double sankyo. One on each side. But Sankyo on both sides won’t work right. So, how to put him down. We shifted the grip to reverse Sankyo, meaning outside hand on the fingers twisting back. Then we added Yonkyo to it. That put uke on the ground. He was yelling “Tase me! Tase me!” So, we call that a San-Yonkyo. It increases the Yonkyo effect. We use it often now in regular Yonkyo application. It causes the arm above the wrist to groove and it’s right over the nerve. Lay your pointer finger up in that groove and apply the Yonkyo press. I feel it works better than either the Iwama or the Nishio Yonkyo’s

Bernie Lau Sensei is truly a piece of history! Thank you for this chance to hear details about his life – 65 years of Aikido, wow! We love it when he stops by the dojo with his warm smiles and cheerful demeanor.

Great article & thank you for publishing Toheis letter too. I was in the middle of that political poo poo show. Took my preliminary black belt test under the Tohei school which meant i couldnt practcie at Aikikai then I refused the black belt because of the politics. i was a kid at 21 and felt I had decide mother and father so left both and went to tai chi for healing.I have all the arts since then and still love aikido regardless of the style. This article and letter gives me greater peace to understanding what the hell was going on back then.I nevere knew the details. Thanks:)