Hoa Newens has trained and taught Aikido since 1967 and currently teaches at the Aikido Institute Davis. Throughout the years, he studied with Dang Thong Phong, Seiichi Sugano, and the late Morihiro Saito. In addition to directing Aikido Institute Davis, he currently serves on the Rank Committee of Takemusu Aikido Association. He has also trained in Wu Tai Chi and Chi Kung since 1987. From these experiences, Newens puts forth his ideas on aikido, republished with permission from his Aikido Institute Davis Blog.

Hoa Newens will be doing a live talk with Aiki Extensions this Friday. Find out more information here.

Overview of the Issue

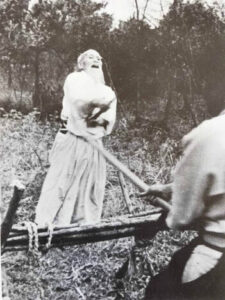

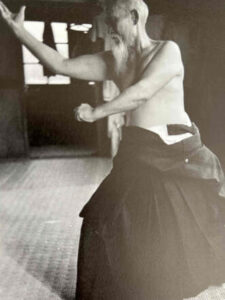

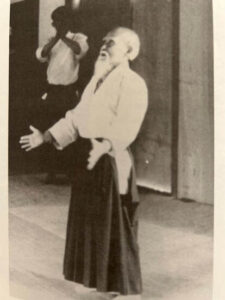

If the purpose of training in Aikido is to lead to a deep understanding of the essence of the martial art created by its Founder, Morihei Ueshiba, then mainstream Aikido training needs an overhaul. After having invested decades in this art, we have become increasingly aware of major deficiencies in our mode of training, which we describe below, together with the correcting measures that we have adopted. Since the Founder’s passing in 1969, there has been no outstanding exponents of this martial art who achieved his level of understanding and who can affirm:

The Way is like the flow of blood within one’s body. One must not be separated from the divine mind in the slightest in order to act in accordance with divine will. If you stray even a fraction from the divine will, you will be off the path. (Morihei Ueshiba, The Secret Teachings of Aikido, p 15, Kodansha International 2007.)

O Sensei expressed his enlightened state through amazing movements and forms, and esoteric lectures. However, he did not share his personal practices; and besides demonstrating his techniques, gave no clear instructions on how to walk the path. His students were left to fend for themselves and discover their own path. To be sure, O Sensei had exceptional disciples who went on to create training systems that shed much light on Aikido for the benefit of the world, namely, Rinjiro Shirata, Gozo Shioda, Koichi Tohei, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Morihiro Saito, etc. Each of these teachers received a different scoop of O Sensei’s teachings and developed it into their own system. However, none of these is sufficiently comprehensive to lead a beginning student to O Sensei’s achievement.

Fast forward to the present time and beside a collection of standard forms (the techniques of Aikido) we have as many different styles of Aikido as there are teachers, with most of these focused on the standard techniques of Aikido. Compared to other more mature traditional martial arts, the present-day Aikido curriculum has the middle section, and is missing the beginning – conditioning and basics – and the tail-end – energetic and spiritual. Stated differently, we received some stems with flowers from O Sensei and tried to grow them, without minding the seeds, and ignoring the fruit.

Many contemporary teachers have made laudable effort to fill the gaps by borrowing elements of other traditions such as Zen, Yoga, Taichi, Daoist chikung, Iaido, Kyudo, Jujutsu, etc. However, oftentimes these elements were imported wholesale into Aikido without the necessary paring and adjustments, resulting in the juxtaposition of incongruent practices with Aikido training, such as doing Yoga asanas or Taichi movements for warm-up in an Aikido class. Ideally, these complementary elements must be distilled into their essential parts before being grafted into the main stem of Aikido and allowed to sprout naturally within the Aikido environment. For example, breathing techniques in yogic pranayama come with Yoga accoutrements, namely terminology, concepts and practices that are intrinsic to this tradition that need to be trimmed down to just the bare essential elements before insertion into the Aikido curriculum.

We have used this approach to distill and refine essential elements from the Daoist tradition, which we believe is closest to Shinto and Aikido; and from selected Chinese wu-shu traditions which we believe were the origins of Budo, to arrive at a comprehensive curriculum that we describe in the balance of this paper.

The Current State of Aikido Training

The present mode of training in most Aikido schools consists of class sessions at a dojo in which an instructor demonstrates a variety of techniques for students to copy and replicate several times with their training partners. Students first learn the general form of the techniques then gradually soak in the more intricate details and refine the movement as they advance. The aim is for students to become proficient in the standard techniques of Aikido, such as Ikkyo, Kotegaeshi, Iriminage, etc. Serious students attend classes regularly (three or four times a week) for several years and build a good repertoire of technical skills. Students are tested and ranked on how well they demonstrate the techniques contained in the curriculum.

This type of training result in enhanced fitness, improved physical coordination and balance, kinetic awareness, and the acquisition of basic self-defense skills. These results surely improve students’ life yet will not lead to the heart of Aikido as conceived by the Founder. As the truly serious seekers dig deeper, they find no roadmap for the depth work, no traveled path that leads to the essence of Aikido. To make matters worse, many of the old arduous methods of training are being gradually diluted and lost.

In the eighties at the Oakland Aikido Institute, before or after classes, students used to practice variations of rolls, continuous tobukemi, tanren-uchi, kokyu extension against each other’s arms, hitting the makiwara, ken and jo suburi, target practice with bokken and jo, etc. These informal training sessions sometimes ran for an entire hour after the formal class. This is a rare sight at dojos nowadays.

The curriculum in most Aikido schools does not include methods that lead to an understanding of Aiki, the universal force oft referred to by O Sensei in his lectures, nor methods to reach the spiritual awareness that caused O Sensei to proclaim that we are one family and Aikido is love. These are two huge gaps in the present-day Aikido pedagogy, causing several derivative deficiencies in training and teaching that will be pointed out below. The Founder did not leave us any method, only various hints here and there in his abstruse speeches, and through his demonstrations. Each of his closest disciples received a different scoop of his vast experience, with none being able to transmit the total experience to their students.

We realized these deficiencies several years ago and have used our experience in Aikido and internal martial arts as a springboard to research and experiment with ways to close these gaps and offer the following recommendations to Aikido exponents.

“O Sensei expressed his enlightened state through amazing movements and forms, and esoteric lectures. However, he did not share his personal practices; and besides demonstrating his techniques, gave no clear instructions on how to walk the path. His students were left to fend for themselves and discover their own path.”

Essential Components of Aikido Training

Aikido is not just a collection of techniques. A well-rounded Aikido curriculum that leads to the Founder’s spiritual achievement must include the following essential components, many of which are missing in present day training.

Essential components of an Aikido training program include:

· Body conditioning (Tanren)

· Code of conduct (Rei)

· Basic drills and techniques (Kihon undo)

· Energy work (Ki undo)

· Breath practices (Kokyu undo)

· Personal training program (Shugyo)

· Study and research (Kenkyu)

· Connection to the sources (Kishin)

· Meditation (Chinkon) and prayer

Body Conditioning

In a typical contemporary Aikido class, the instructor may conduct some warm-up in the form of stretching or calisthenics in the first few minutes; many instructors ask students to do their own warm-up before class and focus instead on teaching the techniques. In more traditional martial arts, the beginning students are required to undergo a serious body conditioning program before being allowed to perform techniques. Horse stance, resistance training, joint strengthening exercises with various implements, even dojo chores, etc. These are tanren (forging) practices that can take different forms. Take a look at the Hojo undo (supplementary exercises) of Goju-ryu karate as explained by Morio Higaonna Sensei in the video below. One can find similar body conditioning in other well established traditional martial arts, e.g., Shaolin, on YouTube.

Training in an authentic martial art requires that the body be properly conditioned to address these five aspects of movements:

1. Stability. The body must be well anchored as a platform to deliver force. In this respect, stance training, including postural alignment, is of utmost importance. The horse-riding stance, the hanmi stance and the hitoemi stance and other footwork should be part of preparatory exercises. This emphasis is sorely missing in contemporary Aikido.

2. Centering. Integrating all parts of the body in any movement through connection with our center is another key principle. Exercises to create and reinforce awareness of the body centerline are crucial. They should be part of Tai Sabaki, Ken Sabaki and Jo Sabaki in Aikido training.

3. Mobility. Moving the body efficiently (with the least expenditure of energy) and effectively (to achieve proper awase) is essential. This quality is acquired through Tai Sabaki work, in which essential segments of oft-used movements are repeated endlessly until they are wired into the body. Tai Sabaki should follow warm-ups and be an integral part of all classes, as well as be a key component of the serious student’s personal daily practice.

4. Flexibility. Flexibility increases the range of movement around joints and improves any movement art. A daily regimen of stretching, both external (lengthening of tissues) and internal (loosening of soft tissues), is a requisite in an Aikido training program. It should be noted that stretching to improve flexibility is not the same as warming up for a work-out and should be done outside of regular classes, e.g., as part of a personal training program.

5. Connection and integration. This aspect of training is often overlooked in mainstream Aikido. This is the aspect of training that helps the different parts of the body to connect with each other through a central axis, thus allowing the body to function as one unit. Practices include stance training (e.g., pole standing), moving the central axis with footwork, rolling practice. Rolling practice (often referred to as ukemi) is a powerful body integrator, besides being a superlative kokyu extension exercise.

Code of Conduct

At the heart of a true martial art lies a rigorous code of conduct that defines and governs one’s interaction with others and one’s environment. Strict adherence to such a code provides the martial adept with the inner strength to plumb the depths of the martial art and face life and death with equanimity. Without this strength of character, the martial artist can only scan the superficial layers.

“The Founder did not leave us any method, only various hints here and there in his abstruse speeches, and through his demonstrations. Each of his closest disciples received a different scoop of his vast experience, with none being able to transmit the total experience to their students.”

Unfortunately, proper etiquette (bowing, deference to seniors, dress code, decorum, etc.,) is disappearing quickly in many martial art circles, including Aikido dojos. We decry this deficit for it is the reason for the popular decline of Aikido and Budo in general. For Aikido to prosper, rei must be restored.

Each dojo should establish and enforce a code of conduct based on these three pillars of martial excellence: awareness, humility, and perseverance. This is not an easy task given that societal trends are going in the opposite direction: chaotic liberalism and supreme materialism are turning heretofore fundamental human values into irrelevance.

Basic Drills and Techniques

This is the domain of current Aikido training, though it is fraught with incorrect focus. Many advanced Aikido students train with the goal of building up their repertoire of complex techniques, thus aiming at the many rather than the depth of few and straying from the return to essence.

There are certain basic exercises (kihon undo) that do not fall in the body conditioning mentioned above and are not complete techniques in themselves; however, they form the core from which techniques are developed. These are:

· Ukemi rolls

· Shikko (knee walk)

· Ashi sabaki (foot work)

· Tai sabaki

· Ken and Jo sabaki

These practices guide the growth of the conditioned body into full-fledged techniques; they are like the stakes that support and guide the growth of young plants. They should be part of the Aikido curriculum and included in regular classes and daily practice.

After having tempered their body, students gradually learn the core techniques and their variations, continuing with increasing complex techniques. As they progress to higher level, around sandan and yondan, they should refocus on technical details and learn to dig for the essence of each technique. For example, work on the intricate details of Ikkyo and understand the essence of this technique: how does the central axis initiate and control the entire technique? What does it feel like when performing Ikkyo or when receiving the technique? Does uke feel like being swept up by a strong wave? The student must put heart and soul into practice until there is a clear bodily feel for this technique.

Each core technique has a signature feeling or sensation that is stored in the body and recalled any time one needs to execute the technique. Students must work hard to discover this signature feeling, rather than entertain themselves with a variety of forms.

Here are some methods to drill into the depth of a technique and extract its essence:

· Slow down the execution of the technique.

· Request uke to provide resistance to test the movement.

· Break the technique into key component moves and rehearse each of them separately.

· Focus the training on the core techniques and repeat their kihon form numerous times.

Energy Work

To truly understand Aiki and facilitate its manifestation in our body, we need to understand and improve the functioning of our energetic system. It is a tenet of a traditional martial art that anyone who wants to achieve excellence in the art must turn inward to find the path thereto. This is the domain of internal energy work (chi kung), from which we borrow key concepts for the purpose of this paper.

There are three centers (tanden, or dantien) that control the flows of energy in the body: one in head, one in the chest, and one in abdomen; all three aligned vertically in the central axis of the body. The strengthening and realization of these centers, specially the one in the abdomen, are prerequisites for the integration of the body as one unit and for the integration of the body and the mind.

“At the heart of a true martial art lies a rigorous code of conduct that defines and governs one’s interaction with others and one’s environment. Strict adherence to such a code provides the martial adept with the inner strength to plumb the depths of the martial art and face life and death with equanimity. Without this strength of character, the martial artist can only scan the superficial layers.”

Though it is obvious that O Sensei has reached beyond this level of integration, the standard Aikido curriculum does not contain the theory nor the practice that would allow students to achieve the above-mentioned unity. They need to keep an open mind, go beyond the standard Aikido curriculum, and dig into the ancient energy practices of the internal martial arts, borrowing from such tradition as Taoit neigong.

Breath Practices

Kokyu means breath and is a concept often used in Aikido. Kokyu ho is the method of the breath and kokyu nage is a breath throw. However, students find scant explanation about breath and a dearth of instructions about breathing practice. Instructors often repeat breathing movements from their teachers or borrow from other sources without understanding the underlying theory.

O Sensei considered that Aikido practice is essentially a purification process (misogi), in which breathing figures prominently, as he explained below.

“All things of heaven and earth have breath – the thread of life that ties everything together. The act of breathing connects with all the elements of heaven and earth. . . The resonance of one’s breath, originating from deep within our spirit, animates all things. Breath is the subtle thread that binds us to the universe. This pristine fountain of existence is where our breath and actions originate, and we must utilize it to purify this world of maliciousness.”

. . .

“The act of breathing, regardless of whether you are conscious of it or not, naturally ties you to the universe; if you advance in training, you can sense your breath spiraling to all corners of the universe. Breathe that universe back inside you. That is the first step in developing breath techniques. Breathe like this and your spirit will become truly calm and settled. This is the initial step in developing aiki techniques. In time, aiki techniques can – indeed must – be performed with no premeditation.” (Morihei Ueshiba, The Secret Teachings of Aikido, p 64-66, Kodansha International 2007.)

O Sensei’s instructions on breathing practices are not specific but are generally consistent with Shinto misogi rites and similar to Taoist practices, which emphasizes natural flow, engagement with Heaven and Earth, and merging with energy and consciousness. Breathing exercises should be a regular part of class practice as well as personal practice.

Personal Training Program

Students attend classes at school to receive new knowledge and do homework to reinforce and absorb this knowledge. Upon joining a dojo, an enthusiastic beginning student may rehearse at home the moves that he learned in classes. Over time, the excitement cools down and the student feels that class attendance is enough training. This is often the trend unless the teacher continuously emphasized the need for personal practice beyond class.

Two problems arise. First, class instruction is generally aimed at the needs of a generic middle-of-the-pack student in the class, and not the specific needs of individual students. Therefore, a beginning or an advanced student’s training needs are not addressed by simply attending classes. Second, in class students are exposed to new details of techniques and have limited time and opportunity to reinforce this new material; the only way to get this new stuff ingrained in oneself is to practice it outside of formal class, either after class or at home. Many students attend classes and seminars given by outstanding teachers, even going to Japan to learn from such; however, they do not engage in a personal training program to reinforce what they learn, and as a result, their exposure to the outstanding teachers has limited effect.

All serious students of Aikido, including instructors of all ranks, should engage in shugyo (ascetic path) and commit to a daily training program that is commensurate with their level.

Study and Research

Rehearsing what we learn in class is a sure way of inculcating new material into our mind and body. However, we must remember that it is only one tiny strand of life, among the zillions of other strands in the vast tapestry of life. Therefore, we must always remain open to new experiences; this is the gist of life, absorbing new experiences. There are numerous other experiences beside those that we had with our teachers that are worth exploring.

As rational beings we use our mind to explore new territories before allowing the body to step into them. Life is movement; to be in sync with this movement, our mind should be constantly awake and scanning the unknown for new possibilities, so that when life throws a curved ball at us, we have ways to receive and engage with it.

The higher the skill in martial arts, the more the risk of narrow mindedness. I have trained for over five decades, I am an expert, why bother with other ways and methods? This attitude leads to dogmatism and stunted growth. If martial arts are our lifelong pursuit, we must be aware of this risk and constantly cultivate humility while continuously studying and researching new ideas and concepts.

An additional risk lies in the fact that most traditional martial arts originated from matured societies which are steeped in culture and traditions. As we pointed out earlier, this is an excellent milieu to build great skills and get grounded, but it is also a trap for intransigeance, e.g., this method has been passed down for several generations and it works, why look for something else? If our teachers hail from this environment, we are at risk of getting out of sync with life, which constantly evolves. “We must always change, renew, rejuvenate ourselves; otherwise, we harden”, counseled the German poet and playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Connection to the Sources

This is the ultimate phase in the physical training of martial arts and is referred to as Takemusu Aiki in Aikido. It is the natural result of all the training aspects mentioned above up to this point. We mention this phase here to complete the picture, but also to warn students that, though this is the ultimate goal, they should not keep it in mind as a training goal; it would be as bad as focusing our training on randori. Doing so would cause the ego to interfere and hamper the training: let it happen naturally in due time.

“As they progress to higher level, around sandan and yondan, they should refocus on technical details and learn to dig for the essence of each technique.”

Meditation and Prayer

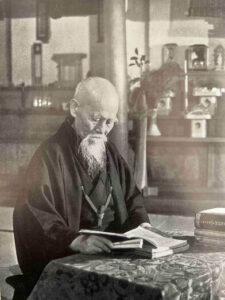

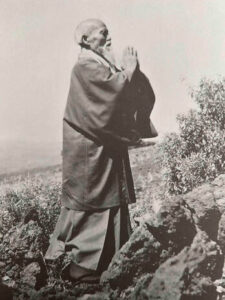

If Aikido is to lead us to union with the spirit deep within us, our practice must include a process for us to shed the mundane detritus that have been piled on us through our unconscious doings. Meditation is the process which helps us to rid this rubbish off us and allows the light deep within us to emerge and rejoin the universal consciousness (Kishin, return to the source). An authentic martial art system that aspires toward spiritual enlightenment has meditative practices that guide students. Within Aikido, it is recorded that O Sensei often immersed himself in meditation (Chinkon) and prayer for hours on his own; however, besides his talks, he did not leave instructions for his students.

We found that Zen meditation and Taoist meditation practices are most congruent with Aikido principles; students should choose one of these paths and deepen their training or refer to our guidelines on meditation.

How to Incorporate New Elements into Aikido Training

Aikido is a relatively modern martial art with room for evolution and refinement. We refine the art by paring it down to the essential components and adding new elements in a deliberate manner. We have discussed at length how to discover its essence in prior papers, for example, “In Search of the Essence of Aikido“. Here, we examine the process of adding new elements. We can say that we have successfully added new elements and enriched Aikido when these elements are effectively integrated with Aikido practice: their underlying principles are consistent with Aikido principles, and they flow seamlessly with Aikido practice. We describe below the process that we have personally used.

When we encounter an element that seems to be useful for Aikido training, rather than adopting it right away in its current form, we should engage in its practice in its native environment. For example, you were impressed by the presence of mind exhibited by an Iaido expert during a demonstration. Instead of adding sword drawing in your Aiki Ken classes; or copying the rituals (the composure, the posture, the bow, etc.) into your Aikido classes; you should enroll in an Iaido school and train in this art for several years until you have grasped its essence. There will be a time when during Aikido training you suddenly realize that a particular aspect or movement feels the same as an element of Iaido. Not until then can you attempt to extract the relevant portion of its essence and transplant it into Aikido training. Just like with any transplant, you should gently guide its growth in the new environment by making the necessary adjustments then allow it to mature with time. Eventually, the transplanted elements will integrate with Aikido practice and take roots in Aikido principles. The process will take a few decades of relentless correction and adjustment and will contribute to the natural evolution of Aikido training. We believe that it is the same process that O Sensei went through to create Aikido from his experience in various martial arts.

Conclusion

Passing on what we learned from our teachers to the next generation is a commendable deed, as long as we are transmitting the seed and not the outer layers or the skin. The seed is what perpetuates the art; we ought to let go of the body and the skin. The latter are merely protective layers that reflect the climate and conditions of a certain time and locale in the past and must now be regrown to adapt to the present surrounding conditions.

In Aikido, the techniques are constantly changing, for change and adaptability are part of the essence of Aikido. I am always training and studying in that spirit, constantly altering the techniques according to the circumstances.

[. . .]

Aikido has no forms. It has no forms because it is a study of the spirit. It is wrong to get caught up with forms. Doing so will make you unable to respond with proper finesse. (Morihei Ueshiba, The Secret Teachings of Aikido, p 15, Kodansha International 2007.)

We must use the knowledge and experience that we received from our teachers as a springboard to chart an evolutionary path for Aikido and carry its essence into the future, lest the art devolves into irrelevance and dies from stagnancy. We must strengthen and give direction to our training, pierce the outer form to find the precious inner core and discover the proper way to preserve it.

Hoa Newens

To hear more from Hoa Newens, join him in a live talk with Aiki Extensions this Friday! Find out more information here.

Techniques without obtaining Kuzushi first do not work in real life .

But for people not looking for self defense , any safe Aikido is super’ exercise and can be tailored for age and abilities . The above opinions are the author’s . Maybe I do not want to stress a lot of conditioning , maybe I do not want the spiritual side , maybe I do not want to practice meditation . If a teacher insists on the spiritual aspect she or he has to make it clear from the beginning and let me decide to joint or not .

A teacher may tell me to get from Aikido what I personally want to get . This is the teacher whose dojo I would join .

Most dojos teach a form not effective for self defense . We have to be honest .

I love Tantodori , but the techniques are not realistic .

There are realistic techniques but most teachers do not know them .

One of the most profound and relevant discourses I have ever become aware of.

kokyu roku + tai no sabaki = ki no musubi

Thank you for this very interesting article with various concrete suggestions for improving Aikido training. While the second part of the article – discussing the role of breath, energy, connection with sources, and a personal training program – clearly demonstrates a connection between the practice of Aikido and the forces in the cosmos that can be experienced and can guide the manifest form, this practice, according to Ueshiba himself, appears to be an (though indispensable) secondary goal.

The primary goal in practicing Aikido for him is Tao/The Way: understanding the functioning of the entire creation and the (process-oriented) subjective sensation of it.

Ueshiba consciously developed or discovered and shaped Aikido to be helpful in achieving this understanding because in the practice of Aikido, one can become aware of Ki, ki, and the creative primal force of the universe (Takemusu Aiki), and one must learn to incorporate these forces/energies into the execution of each Aikido technique. The esteemed author may also intend to indicate this by referring to its ‘Essence’, but it is unclear whether this refers to the manifest expression or its carrier/basis: i.e. the process of understanding the operation of the cosmos (and Takemusu Aiki), through which Aikido could be performed in optimal form. See, if desired, my publication “Ueshiba’s Universe – its Significance for His Aikido”, P.P.J. Overvoorde (2021; Amazon). To better grasp Ueshiba’s philosophical and worldview motivation, as well as his conscious application of it in this modern form of Japanese martial art, I analyzed his hints and often fragmentary statements about it in his profound lectures. I was able to show that he did indeed hold a coherent view, even if he did not present it explicitly in a systematic overview. In my current research, it becomes clear how all of this is embedded in the framework of East Asian classical thought, initially developed in China two thousand years earlier but introduced and adopted in Japan from the sixth century, later supplemented with its own traditions (including Shinto). From this breadth, it becomes even more evident how Ueshiba, starting in the twenties of the previous century, enriched and complemented it with insights to make Aikido what it seems to be in essence for him.

With the valuable suggestions in Mr. Hoa Newens’ article, this insight could certainly enrich the training of Aikido for some practitioners, without compromising Aikido as an effective martial art. After all, that’s what O-Sensei demonstrated.

Vielleicht ist Aikido auch nur das, wonach es aussieht: klassisches (altes) JiuJitsu ohne Randori oder Shiai mit Betonung auf Gesunderhaltung. Für jedermann geeignet, die sich fit halten wollen und sich für japanische Kultur interessieren – O Sensei’s Interesse an Kampftauglichkeit etc…hat doch nach WKll sehr nachgelassen….er wird wissen, warum 🙂

Very interesting discussion of the issues. Trained at the ASU Bellevue for 5 years but left disillusioned because I had trained in White Crane for several years and did not believe the training was effective martially. Was so taken with O’Sensei’s message that I found the Yoseikan in Torrance (the aiki jujitsu line from Mochizuki Sensei) and trained there for 20 years on the theory that the only way I could understand O’Sensei’s path was to study the root in the hope I could understand the flower (his later teaching). This form of the root is not interested in internal martial arts, and my theory is that at some point, by some method not yet understood, O’Sensei’s practice became infused with this understanding of internal energy. At one of Stanley Pranin’s seminars in Las Vegas he passed along a biography of O’Sensei’s Shinto mystic teacher, Deguchi. He seemed to believe that this was part of a transformative process, perhaps initiated with their journey into Manchuria. Ellis Amdur seems to have similar ideas. Even so, the technical source for these practices are unknown. I have continued my search to see if I can find a path into these internal practices by studying Chen Tai Chi here in Seattle for the last 8 years. Because I have some awareness of chi from doing extensive zen meditation at various times, I have wondered how to integrate this awareness into movement. It is only recently that I have had some limited success – in the foothills of that journey as a 73 year old guy, but I am getting a glimpse of why and how the practice changed so dramatically from the root forms I studied at the Yoseikan to what is now available at the ASU/Aikikai – but to my mind, studying the flower is not sufficient unless we find some way into the internal energy. Even my teacher, Auge Sensei, quoted his teacher, Mochizuki Sensei as saying: “O’Sensei could do things nobody else could do.” O’Sensei was truly quite a way up that mountain.

Thank you for sharing your points of view. For insight into the development of O-Sensei from various Japanese martial arts, and its influence on his extraordinary skills, everyone can read the beautiful and profound book by Ellis Amdur, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” The impact of this on the manifested forms of Aikido performed by O-Sensei cannot be overstated. Nevertheless, there was a second powerful influence starting when Ueshiba joined Omotokyo in 1920, a modern Shinto movement led by Onisaburo Deguchi. This spiritual leader, with whom Ueshiba maintained close relationships, encouraged him to develop his martial art as a form of spirituality. In the ensuing decades, O-Sensei worked on this. In December 1940, enlightened by insight from a profound transcendent experience, he realized the far-reaching influence and significance of external universal forces/energies in the universe. He advocated the role of Ki and ki, Aiki, Takemusu Aiki as essential elements in the execution of techniques he selected and further developed for Aikido.

Thank you for this very interesting article with various concrete suggestions for improving Aikido training. While the second part of the article – discussing the role of breath, energy, connection with sources, and a personal training program – clearly demonstrates a connection between the practice of Aikido and the forces in the cosmos that can be experienced and can guide the manifest form, this practice, according to Ueshiba himself, appears to be a (though indispensable) secondary goal. The primary goal in practicing Aikido for him is Tao/The Way: understanding the functioning of the entire creation and the (process-oriented) subjective sensation of it.

Ueshiba consciously developed or discovered and shaped Aikido to be helpful in achieving this understanding because in the practice of Aikido, one can become aware of Ki, ki, and the creative primal force of the universe (Takemusu Aiki), and one must learn to incorporate these forces/energies into the execution of each Aikido technique. The esteemed author may also intend to indicate this by referring to its ‘Essence’, but it is unclear whether this refers to the manifest expression or its carrier/basis: i.e. the process of understanding the operation of the cosmos (and Takemusu Aiki), through which Aikido could be performed in optimal form. See, if desired, my publication “Ueshiba’s Universe – its Significance for His Aikido”, P.P.J. Overvoorde (2021; Amazon). To better grasp Ueshiba’s philosophical and worldview motivation, as well as his conscious application of it in this modern form of Japanese martial art, I analyzed his hints and often fragmentary statements about it in his profound lectures. I was able to show that he did indeed hold a coherent view, even if he did not present it explicitly in a systematic overview. In my current research, it becomes clear how all of this is embedded in the framework of East Asian classical thought, initially developed in China two thousand years earlier but introduced and adopted in Japan from the sixth century, later supplemented with its own traditions (including Shinto). From this breadth, it becomes even more evident how Ueshiba, starting in the twenties of the previous century, enriched and complemented it with insights to make Aikido what it seems to be in essence for him.

With the valuable suggestions in Mr. Hoa Newens’ article, this insight could certainly enrich the training of Aikido for some practitioners, without compromising Aikido as an effective martial art. After all, that’s what O-Sensei demonstrated.

All discussions of Takemusu aiki must begin…and end with Osensei. And then immediately proceed to them showing his unsusual power.

Everything else is just opinion and a clear demonstration of both the lack of intellectual depth of the subject, and a very clear lack of power.

What, prey tell, did he say Takemusu aiki even was?

He twirled a stick. And he pointed to the center. He said “It is the working of the attraction point between yin and yang, this is the birthplace of all techniques….THIS…is my Takemusu Aiki.”

And he went on to say “Aiki is the same, whether you train solo, or with an opponent, it’s the same. It’s what makes aiki so interesting.”

He went further to say:

“Once you understand, you’ll come to realize that aiki is being suspended between heaven/earth/man.”

Virtually NONE of this has even a single thing to do with “their ki” and “your ki” interacting. Virtually nothing. “Center to center” is a modern corruption and myth that only leads to over-cooperative failure, as noted by a never ending stream of Osenseis personal students.

The search for Osensei’s power can never, ever, be recovered in the way modern aikido is practiced.

Mad at me for saying that?

I didn’t. He did!

“This is not my aikido!” He would shout as he stormed in to his son’s post war dojo, made everyone stop, and lecture them on heaven/earth/man and make them start push testing each other.

Rather than assigning that to a grouchy old man, maybe it’s time to take another look at what he was saying and doing, before this once brilliant arts fades into oblivion.

In 30 years I’ve not met a single practioner; shodan to Japanese 8th dan who has the skills and understanding.

While the article is laudable, there is nobody and nowhere to go -within the art-to find what you are looking for. All I’ve seen is; people struggling with pieces and parts of a puzzle they barely understand to going wholesale in the wrong direction.

Thank you for sharing your points of view. However, O-Sensei states that Ki and ki are crucial for the practice of Aikido: he literally says that Aikido is the cultivation of ki. In various statements, O-Sensei has attempted to clarify Ki and ki, as their manifestation in the body, and emphasize their importance for Aikido. Aikido requires a connection with Ki, and those who cannot be supplied with Ki energy will not be able to give optimal form to Aikido. Yin and Yang, in classical Chinese thought, spread and supplemented in Japan from the sixth century, influence the quality of Ch’i. In my previous research for my booklet, I did not come across this insight explicitly in Ueshiba’s own statements. However, I suspect that the connection between Ki and Yin and Yang as background knowledge was known to O-Sensei, given what he presents in his view on the creation of the cosmos. According to him, Yin and Yang acting on Ki leads to the creation of heaven and earth – both Ki as cosmic energy, and Yin and Yang as polar forces, remain active after the creation. In phenomena, a part of Ki, through the action of Yin and Yang, is incorporated as ki and can be manifested in a person through breathing techniques (for Aikido practice). Not only for the proper execution of techniques – as O-Sensei intended to demonstrate to his astonished contemporaries -, but also to become more aware of the workings of the universe (Tao) through practice. What he considered most important, but for which he found few followers.

I’m agreeing with his statement about ki and ki. He ALWAYS stated it works as heaven/earth/man in the body -YOUR BODY- to produce power and aiki; a very, very, different proposition than your ki and an opponents ki.

There is no kokyu without it either.

An important distinction here is that it is NOT my opinion as you stated and thanked me for. It’s fact. Moreover, it produces power. Power that is inarguable, and demonstrable.

More importantly is the untalked about 600 pound gorilla in the room. Where are the people with his power?

They don’t exist in aikido anymore.

Why not?

Because aikido is no longer practiced the way he taught it.

There are those of us capable of displaying his to various degrees, even dangerous degrees and teaching the why’s, how’s, and where of how it all works. We have been forming bonds within and outside the community to help restore the art back to where it used to work and was far more capable martially than what it has become. From shodan to shihan people have once again taken up Osensei’s path over the modern one. As one elderly koryu menkyo said to me. “I got both my shodan and Nidan directly from Osensei. I’ve not felt his power since until today. They don’t teach this anymore in aikido.” To which I replied “Oh from your lips to the internet!”

“Internet?” she replied.

“What do they know? Did they train with Osensei?”

Not without merit, she herself was yet another of many people present when he would come in, watch, get upset and stop class while shouting “This is not my Aikido!” And have them stop while he lectured on heaven earth man and have them push on each other.

Now?

Circle, square, triangle (heaven, earth man) has been completely corrupted to various discussions of technique and opinion: circular throw, corner throws, irimi and entering. All completely baseless and unrelated to the teachings of the man who started it all. What he discussed was an Indian/ Chinese model of opposing ki’s, forces within the body manipulated by the mind of man, heaven/earth/man, well known before him and brought to him by…. Takeda Sokaku, who Ueshiba stated “He opened my eyes to real budo.”

It will take time to fix it, but we’ll see how it goes. People are having fun rediscovering his path. I think it is a critical time for Aikido to re-imagine itself and re-immerge as something capable again.

All very interesting. If only I had £1 for every time someone said, “What O-Sensei really said was….” 😉