How could such an elaborate technical system have developed in the isolated countryside of Iwama if Morihiro Saito were its creator?

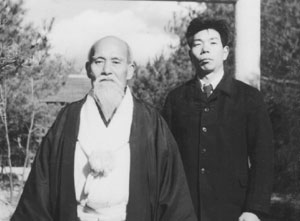

I have always felt that the origin of “Iwama Aikido” presents a conundrum for students of the history of modern aikido. For those unfamiliar with the subject, Iwama is a small town in Ibaragi Prefecture where Morihei Ueshiba relocated during the war. It remained the Founder’s official residence until his passing in 1969.

What is commonly referred to as Iwama Aikido is a vast technical system consisting of taijutsu, aiki ken and aiki jo techniques. The taijutsu component alone includes somewhere in the vicinity of 600 techniques. Add the various weapons suburi and paired exercises and you have well over 1,000 distinct forms. This curriculum is far more elaborate than those of the Yoshinkan, Aikikai, or that of the Ki Aikido of Koichi Tohei prior to his departure from the Aikikai. It is these latter systems that provide the basis for the styles of aikido that spread in Japan and overseas after World War II, rather than that of the Founder. This is not to imply that the Iwama system is superior, but simply that it differs in important ways in content and scope compared to the other major aikido styles.

A fair question to ask is how could such an elaborate technical system have developed in the isolated countryside of Iwama if Morihiro Saito were its creator? Saito had only a middle school education and, aside from a short work assignment in Tokyo as an employee of Japan Railways, spent his life up to the age of 46 years in and around the town of Iwama. His studies of judo and karate as a teenager were brief and superficial, his main influence being his apprenticeship under the Founder starting from 1946.

Many have implied that the Founder was somewhat haphazard in his teaching approach, and in the Iwama years, he left intact a brilliantly conceived and vast martial system.

It should be pointed out that Morihei Ueshiba lived full-time in Iwama from 1942 until 1955, after which he divided his time between Iwama, Tokyo, and his regular travels to the Kansai region. Saito Sensei always claimed that the Founder taught differently in Iwama than he did elsewhere because the dojo was attached to his home and he could engage in training whenever the impulse struck. By comparison, O-Sensei’s appearances at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Tokyo in his final years were sporadic and unpredictable. His irregular schedule did not allow the teaching of a complex technical system in the city. Moreover, the old Tokyo dojo was comparatively small and did not lend itself to weapons practice in contrast to the countryside of Iwama with its ample outdoor spaces. Besides, the Aikikai of the late 1950s and 60s had an experienced cadre of teachers who oversaw instruction.

What then are the possibilities as to the origin of Iwama Aikido? As I see things, they are three: (1) Morihei Ueshiba did teach a technically rich system including weapons in Iwama over a protracted period of time with Morihiro Saito as his leading student. Saito passed on the Founder’s teaching methods essentially intact, changing or adding little; (2) Saito took the loosely-organized aikido basics he learned from the Founder and devised an elaborate curriculum of his own without outside input that is substantially different from what the Founder taught. (3) Saito acquired a deep knowledge of aikido from his long association with the Founder and systematized this body of information into a modern, pedagogically sound system.

The third conclusion seems the most convincing to me. If readers see other possibilities based on available evidence I am overlooking I would be glad to entertain them.

I once doubted that Saito Sensei’s methods were closely rooted in O-Sensei’s teachings because of the apparent differences in their execution of techniques. I based myself on the Founder’s demonstrations in the films from his final years where he performed very few techniques, many of them involving little contact with his uke. On the other hand, Saito Sensei’s aikido was precise, martial and technically diverse. However, I was forced to reevaluate my opinion on this key point following the discovery of O-Sensei’s 1938 technical manual Budo where photos of several key basic techniques are virtually identical to the aikido forms taught by Saito Sensei in Iwama. My later exposure to the more than 1,000 photos from the Noma Dojo series of 1935 reinforced this change in my thinking. Literally, hundreds of very precise and complex techniques stemming from the Founder’s years in Daito-ryu aikijujutsu are preserved. Only a true martial art master could have acquired such a marvelous skill set.

It is these latter systems that provide the basis for the styles of aikido that spread in Japan and overseas after World War II, rather than that of the Founder. This is not to imply that the Iwama system is superior, but simply that it differs in important ways in content and scope compared to the other major aikido styles.

Many have implied that the Founder was somewhat haphazard in his teaching approach, and in the Iwama years, he left intact a brilliantly conceived and vast martial system.

Most of Morihiro Saito Sensei’s Iwama curriculum is organized for rapid review of techniques in his Complete Guide to Aikido.

This is a sincere question (i.e. I’m not trying to start an argument).

I’ve been looking at the Asahi News Dojo film and the recently released material of Noriaki Inoue, and comparing them to the still images in Budo and Budo Renshu.

The still images look quite strong, and look not unlike the way Saito Sensei, or for that matter Daito Ryu’s Kondo Sensei, do on video. (not that I’m blind to the differences between Saito and Kondo – but both seem very precise and powerful.

But the moving images show a very soft, flowing style that is not like Kondo or Saito.

either

a) the still images are intended for beginners and the flowing style we see in the moving images is the fruit of long years of training. Students do it this way, but senior teachers do it that.

or

b) The pre-war style was always very soft and flowing, but the only documentation is staged still photos and drawings so it looks strong and precise, even though it was soft and flowing.

Added to that is Takeda Tokimune’s comment that Ueshiba “did not teach precise techniques” (or similar) which sounds like the sort of thing he might say if he disapproved of the more flowing approach (the quote is from his interview in Conversations with Daito Ryu Masters)

I don’t think either approach is better or worse, but they do look different.

Within the Iwama style are at least two levels of practice. Basic, kihon, almost static technique is most distinctively “Iwama”. Saito Sensei emphasized that was the core of the art. With that more or less in hand the next step is ki-no-nagare, or flowing technique. It is profoundly true, at least in my experience, that the transition from kihon to ki-no-nagare isn’t easy. Through at least shodan, Iwama-style students, myself included, look clunky. However, I’ve been to schools where I sincerely enjoy training with the strong beginners who frustrate everybody else.

I really enjoy [Noriaki] Inoue Sensei. This is because his style takes paths which are very accessible in Iwama style, but not taught. The flow is not the difference I perceive. This leads me to concur with Stan Pranin Sensei’s opinion that Saito Sensei collected and systematized O Sensei’s material into a training method. I honor that he does not appear to have added much of his own material, but in the nature of things he probably pruned some of the branches. His training theme, after all, is riai – that all aikido is really one system.

Recently I’ve been enjoying the new blossoms and leaves of spring. Also enjoying some of the new-to-me material preserved by Inoue Sensei, Shirata Sensei and Daito Ryu.

I agree that the evidence that we have most supports your third alternative. From Saito Sensei’s descriptions of how his teaching methods came about, we know that there are important aspects of his teaching method that didn’t come from Morihei Ueshiba Sensei (the suburi, counting the steps of the kata). I have never doubted that Saito Sensei made these innovations in a sincere attempt to preserve the Aikido he learned from Morihei Ueshiba Sensei.

I would dispute the idea that Iwama Aikido has a more elaborate curriculum than other Aikido traditions. The fact that the taijutsu component has 600 techniques is not that impressive in that I believe I have personally seen a much larger number taught. The fact that I can’t prove that makes what I see as the difference between Iwama Aikido and other traditions; Saito Sensei was able to catalog and organize his curriculum to a degree that is unmatched. The fact is that there is no one Aikikai curriculum. Admittedly, Aikikai Hombu officially lists a smaller number of taijutsu techniques, but I have always interpreted this as giving individual teachers the freedom to set their own curriculum within the framework of the Aikikai. This freedom means that quality will vary (and vary it does), but allows for individuals to progress into individual talent as part of a living art.

Saito Sensei has preserved many of the elements of Ueshiba Sensei’s teaching, but from the record we see that one of the elements was the freedom to make Aikido individual; to allow the student to develop his own understanding of the principles through training.

Saito Sensei’s legacy is the preservation of technical details that he learned directly from O-Sensei, and he should always be honored for his efforts in this regard. However I think that it is a mistake to say that he preserved *all* of O-Sensei’s teaching. I think that O Sensei’s legacy is too expansive for it to be systematized in a set curriculum.

Persons who have questions about the pedagogical framework of “Iwama Aikido” would do well to read or re-read the introductions to Saito Sensei’s first two volumes of his original technical manuals, “Traditional Aikido,” in which he clearly delineates the relationship between the weapons and taijutsu in fully determining a set of a dozen or so basic principles of posture, stance, movement and spirit, which resonate through all of the hundreds of techniques and kokyu practices of the curriculum. I won’t elaborate on all the principles and their manifestation in individual techniques, and the handful of “exceptions to the rule”, but mention two of the most basic. In tai-no-henko we learn to keep our hands in front of center as we move. This is the key to maintaining extension, kokyu power, into the arms We also learn to stand and move in hanmi, which is the key to unleashing the full power of the hips. The bokken and jo must become part of the body in order for their qualities to be manifested fully. These basic principles may have slightly different emphases in various techniques, but they resonate through the whole curriculum, and the full incorporation of these into the body through regular training is the “self-forging” process which makes fluid and spontaneous creation of technique, “Takemusu Aiki” possible. Aikido is like a deep well in which a pebble (of investigation) creates a ripple that resonates through each molecule of water and back again.

I can only speak from my perspective and that lacks both direct contact with Japan and the Japanese language. I’m told that after WWII O Sensei spent a lot of time working intensely on technique. None of us were there. It is possible that the various progressions of Iwama style aikido were the subject of that training.

I only met Saito Sensei in 1974. I have seen some footage of his “style” prior to that time. It appeared more “flowing”. Could he have dropped that in respect for the Founder and his legacy? Saito Sensei is quoted as saying ‘as it takes more than one lifetime to learn aikido, we must preserve it for our training in our coming lives.’ He also said something to the effect that if you lose sight of O Sensei you will lose the path to aikido. Was he preserving the path he had trodden?

I’ve found Iwama style as robust as sand burrs (an interesting survival story of its own). I’ve heard the criticism, “If you do So-and-so’s style of aikido like that, it becomes just another form of Iwama style…’

I’ve also heard that in relation to his latter work, O Sensei said something like, ‘I can only do this because I have spent sixty years doing solid basics.’ Was that, at least in part, what Saito Sensei preserved and is now known as Iwama style?

As for myself, unless my students are just indulging me, maybe 30+ years of solid basics have now enabled me to branch out a bit…

The postwar period in Iwama is the hinge on which modern Aikido turns. That period of study and development was the Founder’s perfection of his art, his masterpiece.

The purposes of O’Sensei’s early demos and those of Saito Sensei in the ’70’s and ’80’s are different.

After the war, the historical record indicates that the Founder had a global vision for Aikido, and Saito Sensei made a tacit or explicit pledge to preserve the Iwama teachings.It’s essentially a global nonverbal language, with an alphabet, words, phrases, which allows for spontaneous communication between otherwise separated individuals. For anyone who knows the teaching of Saito Sensei, they know the emphasis he placed on the needs of the beginner. They also know that he felt that mastery of the basics was the key to the highest, free-est expression of the art. Saito Sensei drew the most direct line for the beginner to the unlimited potential of the art. The longer one trains in Aikido, the simpler it becomes. From my perspective, this simplicity is the source of the magic, the beauty of the art. This is the authority behind Saito Sensei’s teaching, not that he categorized X number of techniques.

I would like to address the issue of the apparent “lack of flow” in Saito Sensei’s approach to teaching. As David points out, there is a definite nod to providing beginners with strong basics, hence the more powerful, less flowing emphasis.

However, I have films of Saito Sensei shot during the 1960s where he would often perform very “flowing” demonstrations, including both taijutsu and ken and jo techniques. There are absolutely beautiful, and full of grace!

Why did this stop? I have my own theory. As Saito Sensei began aging in his late 40s and 50s he started experiencing a great deal of joint pain, especially in the knees. I think he may have been forced to make allowances for this increasingly severe handicap by slowing down his techniques and concentrating on basics. When I first began training in Iwama in 1977, he taught ki no nagare training regularly. This decreased over the years.

What do you other Iwama old-timers think about this theory?

A lot of great comments here. Especially those by Edwin Stearns. I don’t see much of a “conundrum” here. Well known it is that Saito sensei systematized O’Sensei’s technical teaching. However, other sensei’s also have their own curriculums, which can’t be avoided if students are to be graded. Stanley, the “theory” you suggest at the end sounds very plausible to me, though I’m not an Iwama old-timing. Which reminds me, I don’t find it that useful to keep mentioning that Saito sensei does Iwama aikido as opposed to just doing aikido. Seems unnecessarily divisive at a minimum.

It’s interesting to read a comment several months after writing it. Stan Sensei, I’ll weigh in although I’m not one of the true Iwama old-timers, from the 70’s. When I reread the lead article the other day, I had the same thought as you because I’ve been re-viewing video clips of early Saito Sensei demonstrations of the early ’60’s etc. that friends had posted on Facebook or I’d seen on Youtube. Very fluid, although still with that beautiful economy of motion that comes with real power.

I started in ’86, in Oakland. When we were preparing for receiving Saito Sensei for the first seminar I experienced, in ’86, the status of his knees was mentioned. We were told to expect a demonstration of basic principle.

In subsequent years, more emphasis was placed on the structure of the weapons curriculum, i.e., the levels of “start/stop”, “awase”, and “ki-no-nagare” with the emphasis on the two-second pauses, etc. This was the basis for his “aiki-ken and jo” teaching certification. During those years in the late ’80’s and early ’90’s, he was responding to the acceleration of international popularity of the Iwama teaching method. This is what I was getting at in my earlier comment about aikido being an international language. It seems that he was making sure to establish a clear alphabet, grammar, sentence structure for communicating in this great language. To recognize this quality in Iwama Aikido is not necessarily divisive, and it doesn’t limit the great expression of aikido, the poetry, to the “vocabulary drills” and the “conjugation of verbs”. The broader universe of aikido, in all its dialects, is a wonderful thing, and I’m glad I discovered it. Or it discovered me.

As did Stan, I would also like to address the issue of Iwama Ryu being ‘unflowing’.

I understand why someone would say this as I have also experienced very rigid and static Iwama Ryu Aikido. In fact, once as an aikido instructor, I was invited to a shodan advancement where I was informed that , “we don’t lead in Iwama style aikido.” ‘Hmmm, not the Saito style I’ve seen.’ was my inner thought. The shodan-ho definitely did not demonstrate ki no nigare

Having said that, the Saito style aikido I have encountered is some of the most wonderful, graceful aikido available. A perfect example of structure and flow then moving~ together would be Pat Hendricks, dojo-cho of Aikido of San Leandro and a direct student of Saito Sensei, during his lifetime.

I have accounted for this exemplary combination in two ways.

1) Pat Hendricks trained directly under Saito Sensei in a relationship that radiated respect in all directions. By all accounts, she was devoted and he was generous; among other healthy characteristics. There was a healthy and trustful exchange between student and teacher that generated takemusu aiki.

2) Saito Style aikido was still very close to the founder and ‘home’, so the techniques could be shared in a pedagogical fashion while still being free. In short, the style was under no threat of being lost or watered down. So, it was full and not particularly dogmatic to my mind.

It’s reasonable to say that I’m not a historian like Mr. Pranin, but I have spent my entire adult life training in aikido at a soto-deshi level, and as a protege level dai-sensei to my sensei before I opened my own dojo. That relationship was developed with a deep educational basis. As such I’ve seen a lot, researched a lot, and have trained much more than a lot.

While there are many articulate arguments for Iwama Ryu one way or another, I can say from my heart and hara, “Iwama style doth flow!”

[Edit requested by author inserted]

Extremely interesting. And i’m not an old timer at all, i started Aikido in 1998. However, as a person that started Aikido in “Aikikai Style” and after my first dan switched to “Iwama Style” or “Takemusu Aiki”, I discovered the effectiveness of Iwama style, specially on the martial level.

It’s true that other than Iwama style, Aikido seems more fluid, which is exactly the aim of physical Aikido, to react harmonically, fluidly with attacks or energy. But, what if there is no motion? what if there is no energy to go along with? Fluidity won’t work and this is where Iwama style is effective. It teaches how to find the triangle, circle and square in the difficult situations, where the attacker is strong and enjoy his full balance, unlike when he’s in motion whereas it’s much more easier to take his balance and eventually apply the techniques.

Fluidity is not the base, it’s the goal. How can we be fluid in talking a language without learning its alphabets? It’s impossible.

In all ancient Samurai books and teachings we find that the key to do a perfect technique is to do it when we are in our normal behaviour, but an ordinary person’s normal behaviour is different from a martial artist, warrior’s one. So the key is to change our normal ordinary person’s attitude to a normal warrior’s attitude.

As in our human nature we are so much anti change vis a vis our behaviour, it’s imperative to do it progressively, step by step, beginning with the alphabets, which is exactly what Iwama style does.

Finally, as a “Samurai” researcher, i find “Iwama style” 100% compatible with the ancient Japanese ways in martial training.

With reference to Stan’s theory on the lack of flow in Saito Sensei’s later years seems to be plausable as evidenced by the fact that in some cases ki no nagare becomes painful especially on the lower back (koshinage) and shoulder (shiho nage). This is true in my case where ukemi is concerned.

On another note I wonder if the joint pain issue is the reason why some of the higher ranked teachers don’t take much ukemi as they used to.

This has nothing to do with Morihiro Saito, per se, but I’m not sure that the argument about the countryside is all that relevant. Katori and Kashima are pretty far out in the country, and those areas were much more country when those traditions were started. There are other examples as well.

Anyway, the basic premise is correct, I think, Morihiro Saito was the inheritor, not the creator.

Allow me to elaborate a bit more. My comment about the countryside refers to the fact that Morihiro Saito was born and raised far off in the countryside, had only a middle school education, and minimal martial arts experience. There is no proliferation of martial arts in the area as is the case with Katori and Kashima, other than a smattering of judo, kendo, and karate. It’s mostly famous for aikido. Also, Saito Sensei started aikido at age 18 and ceased practice of other martial arts. In other words, he was a neophyte at the time.

One could be lost on a desert island and through daily practice with a questioning mind rediscover the universe 🙂

I have not had the pleasure and honor to train with Stan Pranin Sensei in a long time (since the ’70s). I treasure some of the techniques he taught. There were slightly different paths in the same Iwama territory and the foundation of a very survivable style of ukemi. History has not been Pranin Sensei’s only contribution, though it is a unique contribution, to aikido.

Which Are Best? Flowing Or Static Techniques?

The responses and caring here are a tribute to the insights of participants developed from a high standard of dedicated training. There is really nothing much can be added that will improve on it. One can only say the same thing in different way.

The question, “Which are best? Flowing or static techniques? is a trap for the mind which can lead to partisan detours.

The solid, static basics, (and their variables) not only provide a point of reference for the mind, but are also proven to be functional bio-mechanical predispositions for combat interaction.

During a flow, where an opponent is countering you with all his might (unlike the dojo) you will be able to resolve and to finalise a technique because of the basics. The identification of a basic aiki predisposition in the midst of a “flow,” or flurry of dynamic interaction.

Solid basics enable effective flow.

I’m often astounded to find that many “flowing” practitioners DO NOT KNOW WHAT THE BASIC TECHNIQUES ARE! These individuals try to portray themselves as “aikido” practitioners. I beg to differ. I believe they are frauds.

The basics were a thousand years in development and research to refine what works best. They are not arbitrary or the idle imaginings of some ego.

For the essence and principle of Aikido to manifest itself there has to be a form, a preferred predisposition that facilitates to unlock the aiki.

On this basis the “formless” is based on form and form is based on formlessness. But not waffle.

To discover the basics is hard work. We have to allow the laws of the universe to transform us. We have to experience sweat, tears and exhaustion of body, mind and spirit before we can surrender to a higher paradigm. We have to let go of a lot in order to attain that gain. We have to question till it hurts and also to let go and observe the movements of Nature and the Universe as they emerge through ourselves.

Join solid basics as dictated by necessity and you get flow.

There is no contest between fluid and static techniques. They equally form attributes of training. Static, flowing and dynamic are propounded as all being relevant to the proper study of the art in the aforementioned Morihiro Saito’s Books, “Traditional Aikido,” where he emphasises the need for all attributes of training. Not just one or the other.

It is like the double spilt experiment of physics. Depending on your vantage point you will observe either particles or waves. So which one is it? Both and neither. In the end it’s all the same thing, but only if you incorporate both viewing points, or in this case methods of practice, to discover the core potential that lies deeper when these two essentials polarities of training are reconciled.

To flow effectively without collusion you MUST know the solid basics!

The only commentarary that makes sense.

Stéphane Benedetti 7th dan (and I knew Saito Sensei quite well although I was not a student of him)

re: flow vs. none flow – – –

was it Tohei Sensei who mentions that immediately post-war

O-Sensei was demonstrating “soft” techniques but insisting that

the Deshi practised the “hard” style – – – and that Tohei Sensei had

the experience the first time he went overseas of his hard techniques

not working – until he imitated the “flow” style that he’d seen O-Sensei

do ?

( just to reinforce the start-with-the-:”hard”-techniques then add

“ki-no-nagare” later paradigm – as a definite concept of the Founder’s ????)

If I may I’d like to quote Saito Morihiro Sensei here. He often mentioned to his students that “the most difficult way of performing a technique will be the best way to train”. And I’d like to quote Saito Hitohira Sensei who just recently mentioned casually that static training is really more difficult, even more advanced, than flowing Aikido.

Common belief has it that Iwama Aikido is somewhat simpler, easier to perform than the more involved forms of Ki-no-nagare Aikido. That Kihon means beginner’s training. I no longer think so. Of course flowing blending, early unsettling the attacker’s balance, even preemptively drawing out his Ki are valid and necessary elements in Aikido training. Training in non-resistance both for uke and tori is a must. But the more difficult training of moving correctly and without using physical force from the stalemate of a static grab has no match in developing a strong center and clear understanding of Aikido moves.

So I’m not surprised that Morihiro Sensei in his life apparently developed from a more flowing to a more static style of Aikido. Besides I’ve seen him become extremely agitated when confronted with the notion that Iwama Aikido had no ki-no-nagare and on those occasions he would fire off a series of flowing techniques that simply blew your head off. No “bad knees” there!

Hi Stan.

This is an interesting article. Saito Sensei said to me on a number of occasions that he taught Aikido in a systematic way whereas O’Sensei did not. He told many anecdotes about O’Sensei not showing the same waza twice in a row. Further to that he said O’sensei taught him the basics in a different way to other people because he had difficulty in learning techniques but had an excellent memory, that’s why O’Sensei broke techniques down for him. He (Saito sensei) systematised what O’sensei taught so as to teach it large groups of people.

The techniques are O’Sensei’s, the system is Saito sensei’s. This is how sensei Saito Sensei bequeathed the art of the founder to us. Without this systematisation, the weapons and large parts of the Aikido curriculum would have been lost to us. Iwama style is the library of Aikido in my view. Sensei also said to me that practicing Ki no nagare was great, but he had to focus on the basics to ensure that Aikido was handed down to posterity accurately. He suggested practicing Ki-no-nagare vigorously in my own time.

Whether Morihiro Saito aikido was the same as the founder’s or not ,everybody has their own opinion depending on their depth of knowledge of aikido history, exposure to iwama aikido and the way of thinking. So naturally there are many theories and idieas of what is what. So I won’t express mine this time, but what I do want to say is that I have no doubt that Morihiro Saito sensei was sincere, honest and hard-working man with deepest devotion to the founder, and here I’ve picked some of his quotes regarding the subject. I think they speak for themselves. So here they are:

“I don’t know any aikido other than O-Sensei’s.”

“Many shihan create new techniques and I think this is a wonderful thing, but after analyzing these techniques I am still convinced no one can surpass O-Sensei. I think it is best to follow the forms he left us.These days people are inclined to go their own way, but as long as I am involved, I will continue to do the techniques and forms O-Sensei left us.”

“It is a big mistake to think that there is no ki no nagare practiced at Iwama. The ki no nagare techniques of Iwama are executed faithfully as O-Sensei taught them.People tend to train in a jerky way. And when people do soft training they do it in a lifeless way. Soft movements should be filled with the strongest “ki.” People can’t grasp the meaning of hard and soft because they didn’t have contact with O-Sensei”.

“The aikido world is gradually distancing itself from O sensei’s techniques. However, if the techinque of aikido become weak it’s not a good thing, becouse aikido is a martial art. My practice of aikido is always traditional, the old-style way. Now I am looking after my senseis dojo, also, I am guardian of Aiki shrine, the only one in the world, many teachers create their own techniques, but I can’t do that, i’ve got hardened head, I am following exactly the teachings of my sensei.”

“O-Sensei taught us two, three or four levels of techniques. He would begin with kata, then one level after another, and finally, it became just so… and now I teach in exactly the same way. Because O-Sensei taught us systematically I’ve got to teach in an organized way, too. Generally speaking, 0-Sensei would make remarks like the following: “Everything is one. Everything is the same.” He taught us in that way. I’m just following his example.”

“When O-Sensei explained Aikido he always said that taijutsu (body techniques) and ken and jo techniques were all the same. He always started out his explanation of Aikido using the ken. Although he didn’t use a one-two-three method, he always taught us patiently and explained in detail what we should do.”

“O-Sensei also drilled us in a step-by-step manner. I am simply trying to make this method my own through hard study and to have others understand it. As I follow 0-Sensei’s instructions my students are appreciative.”

“O sensei would say: “That’s not the way. Every little detail should be correct. Otherwise, it isn’t a technique. See, like this… like that!” I was very lucky O-Sensei taught me thoroughly in detail, and I’m following his example.”

“When I starting teaching myself I realized O-Sensei’s way of teaching would not be appropriate so I classified and arranged his jo techniques. I rearranged everything into 20 basic movements I called “suburi” which included tsuki (thrusting), uchikomi (striking), hassogaeshi (figure-eight movements), and so on so it would be easier for students to practice them.I was taught first how to swing a sword. I organized what I learned and devised these kumijo and suburi for the sword. O-Sensei’s method may have been good for private lessons, but not for teaching groups. In his method, there were no names for techniques, no words.This was why I organized the movements into tsuki (thrusts), uchikomi (strikes) and kaeshi (turning movements) and gave them names.”

“I saw nothing but the real thing for 23 years, I don’t really know anything other than iwama style, my role is to preserve these teachings. That’s the main thing.”

“For weapons only, I devised a series of exercises based on O sensei’s teachings in order to correctly preserve and disseminate O sensei’s aiki ken and aiki jo .This is the only way, and by issuing weapons diplomas and scrolls I hope to achieve this goal.”

“I am not free to change my style of aikido. I did not change a single technique of O sensei.”

Marius,

Thank you very much for this excellent compilation of quotations from Saito Sensei, most of which have been culled from Aikido Journal’s interviews over the years. Well done!

Very interesting points being brought up here. My opinion is that Saito Sensei considered very carefully how he could promulgate the aikido he learned from O-Sensei as best possible. It is much easier to do ki no nagare forms when you have a solid foundtaion in kihon. I remeber Sensei teaching ki no nagare forms often during my 18 years of training under him, both in Japan, at the many seminars we arranged with him in Denmark, as well as at seminars throughout Europe. Please note, however, the correct progression in the teaching form that was so strongly emphasized by Sensei: you always start a given technique in Gotai / Kihon form, then progress onward to Jutai / Awase and on to Ryutai / Ki no nagare. He would occasionally emphasize that certain techniques did not have a Kihon form and were therefore only done as Ki no nagare, but this was more the exception than the rule. I believe that when he put most emphasis on Kihon forms, he was trying to create as strong a foundation as possible for the students’ techniques. Just as he often would say at the seminars: If you want to train hard or fast, do so when you return to your own dojo. At the seminar, we are here to learn the correct form of the technique, so we as students should train carefully and precisely, I believe that he wanted the students to learn the fine points of the techniques in a clear and precise Kihon form. Then we could add flow as we progressed.

Sensei’s flowing form was beautiful to watch – clear, precise and very harmonious. It was also amazing to be uke for him – you felt very safe but completely “absorbed” by his technique.

So to sum it up: there was most definitely flowing form training taught by Saito Sensei, but the emphasis was on Kihon. I believe that some students tend to get stuck in just training the Kihon level. I try to follow Sensei’s teaching method by going through the kihon / awase / ki no nagare forms of a given technique. By doing so, even beginners can learn to do the flowing forms.

In aiki

Ethan Weisgard

Excellent observations, Ethan! Thank you.

What if the pain in the knees comes precisely from the fact that ki no nagare was not often enough used? Other senseis, including osensei, did very flowing techniques into their latest years. There’s people like Shigeo Kamata (student of Kenji Shimizu sensei) that took up aikido precisely because of such pains in arms or legs, in order to recover some health through ki flowing etc. I am in no position to judge why and how, but the emphasis on basics seems to have taken its toll. There is also the risk of obsesively focusing on details to the point that one fails to see the forest for the trees (the goal in aikido is not a wrist or a lock, but the movement of the whole body, the way it relates to the partner, the environment/universe etc.)

“What if the pain in the knees comes precisely from the fact that ki no nagare was not often enough used?”

In Iwama, I heard that O’Sensei also had lots of pain in his knees. In fact, I was told that, after being some time in seiza, he had to be helped to stand up by two deshi, each one holding an arm. After lifting his body up, O’Sensei would slowly stretch his legs until he could stand up, by himself. Sometimes the deshi also had to massage his legs. I have to confirm this story…but if confirmed…it does not vouch for your theory. Well, in a way…

It is my believe – and, of course, because I was taught by Sensei – that by focusing on kihon, all the details of each technique become evident. This would not happen with more ki no nagare practice. Indeed, we learn how to see the whole forest and know each one of the trees, as well.

Then one can “test” the technique through ki no nagare – flowing – practice. If it is not yet easy enough to do the same technique [it is always difficult, from my point of view], then one should keep on practicing kihon. It is my belief that, as we age, our bodies change and also the way we have to lead with other younger and stronger partners. Without proper kihon practice, we cannot effectively apply a technique on these full-spirited younger practitioners. Kihon is always necessary, especially with aging aikidoka. I am talking about proper kihon, of course…but this is another matter.

On the other hand, if you practice only kihon, you will not learn aikido. This goes for taijutsu and bukiwaza training, of course.

Then, again, we all have our different points of view…and this is wonderful too.

I believe the situation you are describing with O-Sensei was in his later years. He certainly did not have pain that prevented him from moving well in his 40s, 50s, 60s, and early 70s. Kihon and ki no nagare are both essential.

Another theory as to why Morihiro Saito Sensei reduced the flowing techniques in his teaching, might be that as plenty of other techers showed (only) ki-no-nagare, he felt the urge to balance this. Thus Saito Sensei focused more on katai (hard) training, as this was what he figured was missing from O´Senseis syllabus in the aikido taught around the world. This can be one interpretation of his statement to “preserve O’Senseis techings,” the part that he had better grip of than anyone else. Also he was one of the few (?) to have received these detailed teachings from O´Sensei.

My sensei (an Iwama veteran) tells me that Saito Sensei often told him to go train with other masters, but always to return to Iwama for the basics. Statements like this can also be read in numerous interviews with Saito Sensei, some of which are published here on AJ. This also shows that he took it upon him to guarantee that the basics of aikido would not be lost.

As it comes to his knees, I figure 23 years of taking ukemi for O’Senseis, much of which was on hard wood floors, can break anyone’s knees.

Lots on the difference between Kihon and Ki-no-nagare. For me, I think about other things in motion.

A car can move because the tire is well rounded and inflated, and is attached to a firm axle. No shape, no center, no support that keeps the tire upright, no road for friction, no engine; no movement.

Movies and cartoons are static images shown in succession. Badly drawn or blurry static images, the overall flow of the clip is affected. Static is present at every millionth of a second of flow. Have good structure, you can learn to move with it. Have bad structure, no amount of flow will compensate.

As for the freedom to create new systems in Aikikai, it looks like the Aikikai is working to solidly define Aikido and the Aikikai style. For many years, there were definite styles and anything else was Aikikai; I am not sure that is still true.

[…] aikidojournal.com/2016/01/26/the-iwama-aikido-conundrum-by-stanley-pranin-3/ […]