The following is an excerpt from the newly released Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, which contains in person accounts and insights with many of the closest post-WWII students of the founder of aikido, including T. K. Chiba Sensei.

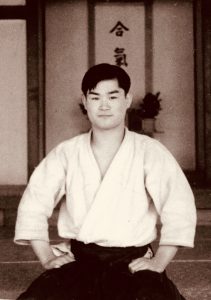

T. K. Chiba was born in 1940 in Tokyo, Japan. At fourteen years of age, he began studying judo; two years later he began studying Shotokan karate. In 1958, he discovered Aikido and began seven years of intensive live-in study as an uchideshi at Aikikai Hombu Dojo. By 1960, he had earned the rank of sandan (third-degree black belt) and was dispatched to the city of Nagoya to establish a branch school and to serve as its full-time instructor. In 1962, he was awarded fourth dan rank and began instructing at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. Within three years, during which time he taught at many local universities, he completed his training as uchideshi, and was promoted to fifth dan.

T. K. Chiba: The important issue today, however, is that if you think of aikido as a tree, it has to be made very clear who is going to take the role of the leaves and branches and who is going to take the role of the roots and trunk. As long as there are people taking the roles of roots and trunk, then the tree remains solid and healthy, and branches and leaves will appear. Then there’s nothing to worry about. People should keep this in mind and avoid insisting that aikido shouldn’t be the way it is now. Leaves are leaves and branches are branches, and these are fine in and of themselves. They’re parts of the tree. The question is, who is going to take responsibility for maintaining the roots and the trunk?

In principle I think there is no old or new in budo. We have the word kobudo, which literally means “old budo.” Its logical opposite would be shinbudo, or “new budo,” but we don’t actually use such a word in Japanese, do we? The modern trend is for new budo to become sport-oriented. It’s probably okay to call these sports “new forms of budo,” but in the traditional way of thinking, sports really don’t qualify as budo.

It’s very difficult to say to what extent these things are to be considered budo. But to my way of thinking, there is no doubt that budo is what forms the roots of aikido. The branches and leaves grow out of that. All the other elements—aikido as “an art of living,” as a means to better health, as calisthenics or a physical aesthetic pursuit—all of these stem from a common root, which is budo. That they do so is perfectly fine, but the point is that they’re not the root themselves. O-Sensei always stressed that “Aikido is budo” and “Budo is aikido’s source of power.” If we forget this, then aikido will mutate into something else—a so-called “art of living,” or something more akin to yoga.

Stanley Pranin: Would you talk about that from a technical perspective?

Within my limited experience, what captivates me most about aikido is its rational nature and the fact that we find coherent principles permeating the whole of aikido technique. To give an example, among the many principles involved in aikido, we find the principle that “One is many.” Empty-handed techniques, in principle, contain the potential to be transformed at any time into weapons techniques and vice versa. Techniques used to respond to a single opponent can be applied just as well to multiple opponents. The lines of movement evolve from empty hands to weapons and back again, from a single opponent to multiple opponents and back again in a continuous, connected, organic fashion. In that sense aikido is very much like a living entity.

This element constitutes one of aikido’s essential qualities as a budo. This is the kind of movement that O-Sensei used and it lies at the heart of aikido.

However, this essential quality is not clearly manifested in the individual techniques so much as it permeates the art as a whole and exists as a latent potential. It allows an approach to an ethic sought by modern spirituality; in other words, the shinmu fusatsu that represents the highest ideal of Japanese budo: “to kill not.”

Aikido’s essence as a budo is by no means close to the surface, but those with a degree of insight should be able to discern it. The aikido that we see on the surface—in other words, much of the aikido we see today—cannot necessarily be said to represent budo in the traditional sense of the word. Fortunately, in aikido there remains the potential for serious students to dig deep to discover its essence, and through a long process of searching, to make that essence their own.

“O-Sensei always stressed that “Aikido is budo” and “Budo is aikido’s source of power.” If we forget this, then aikido will mutate into something else—a so-called “art of living,” or something more akin to yoga.”

I think perhaps one of the profound and fascinating qualities of aikido is that it maintains at all times both symbolic, phenomenal forms available on the surface together with an underlying potential to unfold, revealing the true essence of the concept of bu. In that respect its depth is almost limitless. It’s a great mistake to think that what is visible on the surface is everything and represents reality. On the other hand, exclusively pursuing the so-called “reality” that exists behind the form may cause you to lose sight of aikido’s universality as a path (michi), and all of [Kisshomaru] Doshu’s efforts will have been for nothing.

Doshu’s approach to aikido involves leaving and then transcending the realm of the martial (bu). Central to this is his clear emphasis on the universality of aikido as a path. Doshu turns a critical, introspective eye on certain inhuman, unethical, and vulgar aspects inherent in budo, seeking assiduously to liberate aikido from these negative elements. As I get older, I think I’m gradually coming to a greater appreciation of Doshu’s feelings on such matters, and I look to him with deep respect for his great efforts.

Also, large, round, soft movements, as well as ideas like spiritual harmony and unity, are important, but too much emphasis on them yields a one-sided or skewed approach to training and cannot be said to embody the essence of budo. Those things also tend to lack a certain degree of technical validity. They’re more akin to leaves and branches, and as such perhaps they are better interpreted as being symbolic of the aikido philosophy. They fulfill a role within aikido’s dual aspects of outer appearance and underlying reality. O-Sensei always said very clearly that those aspects of aikido apparent as outer form necessarily have to be budo. He said, “The source of aikido is budo. All of you must first master budo, but aikido goes beyond budo.” He also said, “From now on, the general public does not need budo as such.” He stated these things very clearly.

“However, this essential quality is not clearly manifested in the individual techniques so much as it permeates the art as a whole and exists as a latent potential. It allows an approach to an ethic sought by modern spirituality; in other words, the shinmu fusatsu that represents the highest ideal of Japanese budo: “to kill not.””

In this way, O-Sensei opened a path for the many types of people who had in the past, for whatever reasons, been excluded from the world of traditional budo—people with frail bodies, people lacking physical power, the aged, women. He did away with competition and in so doing created a way that adapts to the capabilities and characteristics of each individual, drawing out their latent potential, and allowing them each to find their niche and fulfill their own mission in life. A world in which people can live together is created when everyone is fulfilling their own potential in this way. That is my understanding of O-Sensei’s thinking.

The full dialogue with Chiba Sensei in included in Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, along with accounts from Seiseki Abe, Katsuaki Asai, T.K. Chiba, Seishiro Endo, Masatake Fujita, Shizuo Imaizumi, Kayoichi Inoue, Hiroshi Isoyama, Mitsunari Kanai, Yasuo Kobayashi, Shoji Nishio, Mitsugi Saotome, Masando Sasaki, Kenji Shimizu, Seichi Sugano, Hiroshi Tada, Hideo Takahashi, Mariye Takahashi, Nobuyoshi Tamura, Moriteru Ueshiba, and Yoshimitsu Yamada.

Interesting to my sensei sitting third from the left.

Thank you Josh for re-publishing this interview that Stan did of Chiba Sensei. This sounds very close to how I remember Chiba Sensei speaking. As a side observation, I was always so impressed with the depth of his intellect and his ability to express himself, in English. Keep in mind that he was self taught. He told me that when he arrived to teach in England that he learned english by translating the Bible.

I remember Chiba Sensei saying that there may only be one half of one percent of all the aikido practitioners in the world who are actually practicing Budo, and that the rest are the branches and leaves. But he continued, that half of one percent is enough to protect the image of aikido as a martial art and to keep it relevant to society. He would add that whether the branches and leaves (Some days he referred to them as the dancers) knew it or not, their existence depended on the trunk and roots. In my opinion, Aikido Budoka need to have some experience with true adversity. That’s where I feel, cross training comes in. Chiba Sensei did it. O’Sensei did it.

However, I feel that martial tempering of the mind, body and spirt can be achieved from the classical training of aikido, even without cross training. People who may have no interest in martial effectiveness, can use their aikido training to forge an effective approach to their lives and experience great fulfillment. To add to what Chiba Sensei said about Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s teaching approach, Doshu taught aikido in a way that was palatable to a broad swath of society that was interested in self-improvement. But he also left room for those wishing to explore the martial effectiveness of aikido, those who wanted to get down in the mud, to become the roots and trunk.

In my dojo, I do my best to introduce my aikido students to the rudements of my background in BJJ and striking arts as part of their curriculum. I give them an opportunity to do some light sparring so that they can learn to be spontainious under stress. I don’t push it much. I leave it up to each student to pursue an emphasis on martial effectiveness or not. In that way there is room at the dojo for the roots, trunk, branches and leaves.

I don’t expect my students to be mixed martial artist, but I do expect them to have good self-defense skill at least by the time they make it to shodan. Anyway, thanks again Josh for presenting this article.

Indeed!!!!!!!!

Thank you for your insightful comments, Bruce. I have a lot of respect and admiration for what you’re doing at Tenzan Aikido in Seattle, and through the seminars you teach.

This is a great excerpt from a great book. It is a pity that a book of this importance would specifically exclude one of the most influential teachers of aikido in the post-war era– a true aikido pioneer–Koichi Tohei Sensei. This stance continues to demarcate the rift that exists between ki-aikido and aikido. In the years that followed the war, there was no such separation, only serious aikidoka and uchideshi doing their best to share the principles taught by O Sensei. Why the omission in this new book?

This book focuses on the pre-WWII students of the founder. Koichi Tohei is prominently featured in the Aikido Pioneers: Prewar Era book.

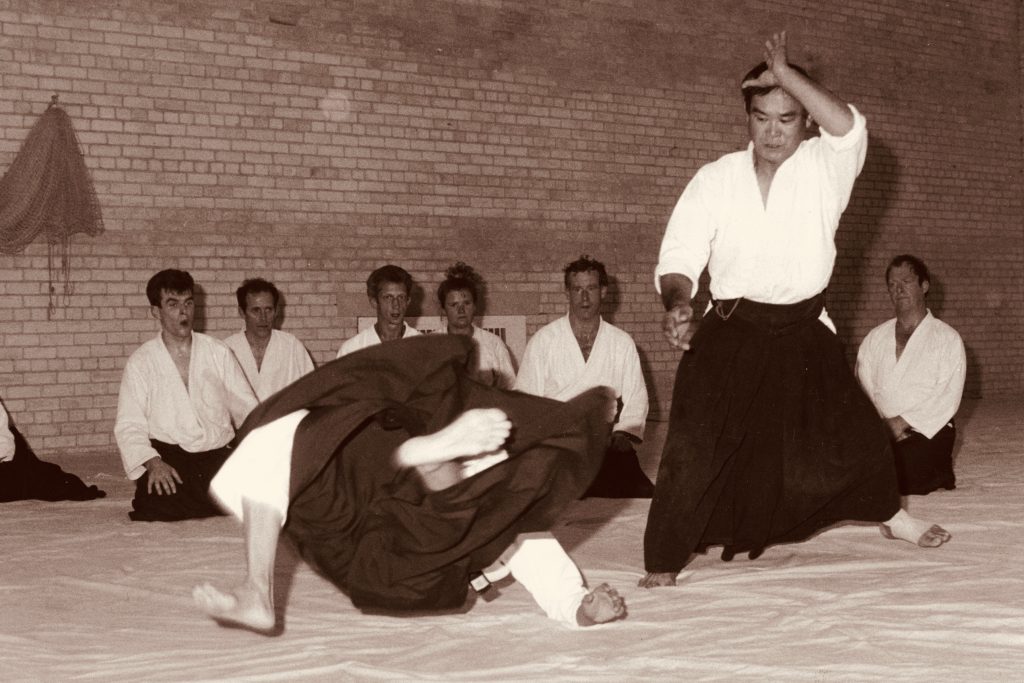

Training deep in the “roots” of aikido with Chiba sensei in the 1970’s was intense – both frightening and enormously exciting. Most mainstream aikido dojos prefer a nice “workout,” a comfortable practice where grace and artistic beauty are most valued. Those are the branches and flowers of the art Chiba Sensei referred to and that approach is wonderful too.

Training one way or the other is not so difficult. My attempts to integrate both approaches has been very challenging, both frustrating and fascinating. A lifelong joyful struggle that keeps me coming back to the dojo year after year. I do find help

for this effort from two sources:

* Kisshomaru Ueshiba lead his ukes into very vulnerable positions where he often used atemi, but he did it so subtly it was hard to nice, so all that was obvious was the beautiful fluidity. He showed me you can be martial, but be subtle about it.

* My other tool for integrating budo into more “casual” training venues is what Morihiro Saito called “Waza wa kibishku, nage wa shizuka ni.” It means engage and unbalance uke with initiative and high energy, but finish (throw/pin) very carefully. With your partner’s safety a priority. Perhaps this may help others attempting to bridge both approaches to training.

Speaking very much as a leaf on a branch, I think I got a glimpse of people training ‘deep in the roots’ when I visited Japan last month. I attended a few classes at Hombu dojo and was lucky enough to attend one of Miyamoto sensei’s classes. The way he interacted with his ukes was so interesting – he had an undeinable sharpness to his Aikido, a definite martial quality, but every time he made contact with an attacking uke, you could see he was searching for something. You could tell even at this point in his journey he was still deeply ‘researching’.

On another particularly busy class, I was struck by two senior students who were practising on the hard floor at the back right corner of the dojo. Their intensity was something to behold. I think it was something approaching what Chiba sensei was talking about in this interview. It certainly put my own practice into perspective, but I think I’m at peace with my place as a leaf on a branch.