The following is an excerpt from the newly released Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, which contains in person accounts and insights with many of the closest post-WWII students of the founder of aikido, including Mitsunari Kanai Sensei.

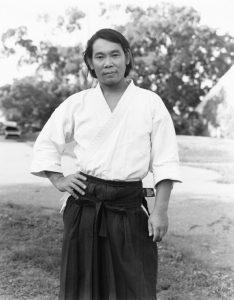

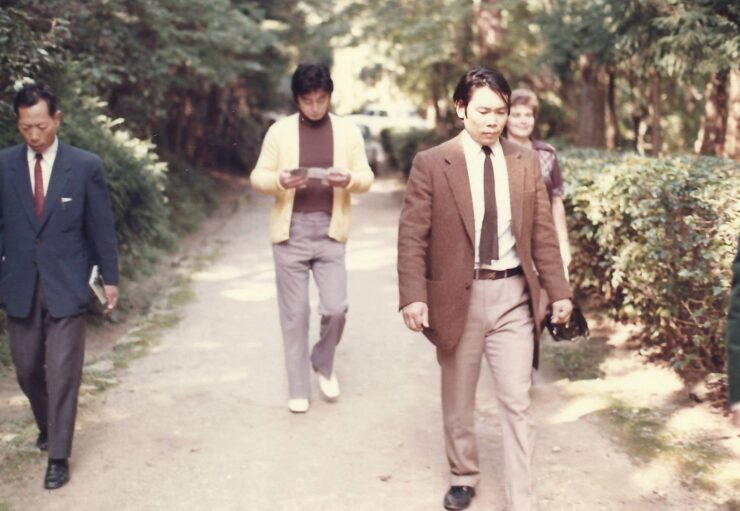

Mitsunari Kanai was born in 1939 in Manchuria, where his father was a military policeman for the Manchurian railroad; the family returned to Japan at the end of World War II. After graduating from high school, he went to work for a typewriter company, but before long began to reflect seriously on what he really wanted to do with his life. Although he had studied judo since childhood, he became dissatisfied with it, and decided to study the relatively new martial art of aikido. He knew of aikido mainly from televised demonstrations, word of mouth, and an early book written by O-Sensei’s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba. Nonetheless, he quit his job and presented himself at the Ueshibas’ school in Tokyo, Hombu Dojo. Eventually, he was formally accepted as an uchideshi. He studied with O-Sensei for close to eight years. In 1965, Hombu Dojo received a letter from a group of martial arts students in Boston asking for a teacher. Kanai Sensei was sent to teach what had been estimated as sixty students; in fact, there were only six. The early years were difficult both financially and culturally—but he had staked everything on the attempt to establish aikido in Boston on his own terms. Eventually, the students began to come. Over the next thirty-eight years, close to six thousand students studied at his dojo, New England Aikikai; thousands more trained with him in Japan and at seminars throughout the United States, Canada, Central and South America, and Europe.

Mitsunari Kanai: Aikiken is so different from the older sword work. Since the subject of the sword has come up, let me give you my ideas on it. Aikiken is the use of the sword as one part of the body. That is to say, it is uniting the sword and body into one, to make it an integral part of the body, and to move in a way that is not reliant on the sword. In other words, to use the sword in accordance with the rules of body movement. I think this is the sword of aiki. I think this swordwork is extremely easy for people doing taijutsu [body arts] to understand. Ultimately, it is to put yourself in the center and to unify. Many types of kendo have developed, and each has its own point of view, so I tend to watch them sympathetically, mainly because I can’t understand them that well myself. However, there is a theory of the sword that is separate from the body. It’s not the body, but the sword. I think a kendo man is a person who strives to utilize to his maximum advantage such things as the construction of the sword, the angle of the blade, the curvature, and hilt length. In summary, to unite the body with the hands and make this unification the sword. Simply stated, the main attention is to the sword, not the body. The sword itself is your spirit. The body is concentrated, then made into the sword and used as the sword. This is my personal understanding of the “Way of the Sword” (ken no michi). Actually, I hadn’t noticed this, but one time I was invited to visit the dojo of a teacher called Sakaguchi and they graciously demonstrated for me. I was stunned. I realized that my swordsmanship was mere child’s play. They certainly had something that no one could criticize. They had completely thrown off the self and had become their swords. In this lies the technique of kendo, and I don’t think anyone can find fault with it. I was greatly impressed by their use of the weapon, their complete unity with the sword, their tremendous concentration. I thought to myself, this is really what is meant by ken [sword]. I think what we are doing in aikiken is really body technique. To put it clearly, it’s taijutsu.

I’ve done a lot of thinking on these things, but many contradictions still remain. If we move in accordance with the rules of taijutsu, then we contradict some of the principles of the sword. On the other hand, we are bujutsu, so it can’t be right to become the sword itself. I’m still just a beginner, so, I can’t grasp this part of it yet. I’m having trouble with it just now. And another related problem is the teaching that says it is not a question of the sword or the body but of kokoro [mind, spirit, heart]. Wasn’t it the priest Takuan Soho [Miyamoto Musashi’s teacher] who expressed the concept that the movement of the kokoro is the sword? It is the body. Didn’t the history of the sword change after that? I’ve seen this dilemma in traditions where the sword is used: is it the body, the sword, or the kokoro that is of the essence? In the old days, a sword was a sword, and the body was the body.

“Aikiken is the use of the sword as one part of the body. That is to say, it is uniting the sword and body into one, to make it an integral part of the body, and to move in a way that is not reliant on the sword. In other words, to use the sword in accordance with the rules of body movement. I think this is the sword of aiki. I think this swordwork is extremely easy for people doing taijutsu [body arts] to understand.”

Things were more clearly kept apart. If we keep strictly to the theory of the body, then aikido’s swordwork is derived from body movement. But that’s not the whole story, because there are people who “throw away” their bodies and live as if they have become one with their swords. I, for one, could never criticize this because I was so impressed by it when I saw it. So there seem to be three points of view. That of Takuan, who said that more than kendo, the person is important. What this heart or spirit of the human is we discover through training, through shugyo [austere training]. Taking command of the human heart is not a matter of ken or Zen (isolated from the rest of life).

This is the view of Takuan. Another is to unify the self with the rules of the sword only. Last is the view we follow (in aikido), to use the sword according to the rules of san-tai [lit., three bodies]. These are the three ways of looking at the question. My problem of late has been just how we can possibly bring these three together into a unity. Though I think O-Sensei’s swordsmanship was a wonderful thing, I still think that to find a way of life through which a person like myself can raise the level of his so-called ken to that pinnacle is an immense task. To be frank, at this point, I don’t know which view to take. But since I am an aikidoka, I use the ken in aikido.

If it is true that the swordwork of aikido is performed on the basis of the principles of body arts, then I think people who train only in taijutsu should be able to pick up a bokken or jo and use it. Certainly, nowadays, jo and bokken classes are very limited. It’s a matter of space. You need an appropriate area to train in and so, generally, the practice of aikido has centered on taijutsu.

The full dialogue with Kanai Sensei in included in Aikido Pioneers: Postwar Era, along with accounts from Morihiro Saito, Seiseki Abe, Katsuaki Asai, T.K. Chiba, Seishiro Endo, Masatake Fujita, Shizuo Imaizumi, Kayoichi Inoue, Hiroshi Isoyama, Mitsunari Kanai, Yasuo Kobayashi, Shoji Nishio, Mitsugi Saotome, Masando Sasaki, Kenji Shimizu, Seichi Sugano, Hiroshi Tada, Hideo Takahashi, Mariye Takahashi, Nobuyoshi Tamura, Moriteru Ueshiba, and Yoshimitsu Yamada.

Is there any contribution from Michio Higitsuchi Sensei?