Part 1 – The Life of Kenji Tomiki

Among the many distinguished disciples of Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido, Kenji Tomiki stands out for his intellectual stature and skill in articulating the historical and ethical rationale of the art. Whereas the founder viewed life and, consequently, his budo, mainly in religious terms, Professor Tomiki espoused a view of aikido that included competition and placed it within the larger context of the history of Japanese martial arts. An academician as well as an athlete, Tomiki authored several books and formulated a theoretical basis for aikido that was understandable by the average person. In this article I will touch upon Professor Tomiki’s background, his relationship with Jigoro Kano and Morihei Ueshiba, and his contributions to present-day aikido.

Early education

|

Kenji Tomiki was born to a family of landowners in Kakunodate, Akita Prefecture on March 15, 1900. It was there that he received his primary and secondary education and his academic and judo talents began to manifest themselves at an early age. Tomiki received a first dan in judo in November 1919. Following graduation from high school, he set out for Tokyo to prepare for university entrance examinations, but became very ill and was confined to bed for three-and-a-half years. During this time Tomiki received much encouragement and support from his uncle Hyakusui Hirafuku who was a famous painter of the time.

After several years lost to illness, Tomiki finally succeeded in entering Waseda University in 1923 where he studied Political Economics. He joined the highly-touted Waseda Judo Club, advancing to the rank of fourth dan by his senior year. It was during this period that he began to frequent the Kodokan and first met the great educator and judo founder Jigoro Kano. Professor Kano’s thinking had a profound effect on the young Tomiki, particularly his view of judo as a vehicle for self-improvement and physical education. Tomiki would later expand on this philosophy of education and apply it in a unique way to aikido. His devotion to judo during his university days did not, however, cause him to neglect his studies and he maintained his academic standing being dubbed “the scholar from the sports division.”

The judo founder even sent several of his leading students, the best known of whom being Minoru Mochizuki, to train under Ueshiba in 1930.

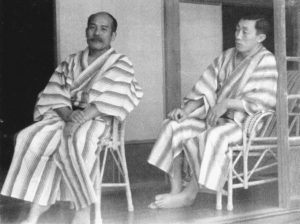

|

Meeting Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba

It was in 1926 that Tomiki first met Morihei Ueshiba via an introduction from a senior in the Waseda University club named Hidetaro Nishimura. Nishimura was also an Omoto believer and had become aware of Ueshiba’s activities through his connection with the religion. Tomiki was highly impressed by Ueshiba’s mastery of jujutsu techniques.

After graduation from Waseda in 1927 with a degree in political science, Tomiki entered graduate school majoring in economics. During the summer of that year he spent a month of intensive training in Daito-ryu aikijujutsu under Ueshiba Sensei at the Omoto headquarters in Ayabe, near Kyoto. Ueshiba relocated to Tokyo later that same year and Tomiki continued his training often taking ukemi for his teacher during demonstrations. By the standards of those times, Tomiki was quite large and powerful and it was an impressive site when observers saw the diminutive Ueshiba handling him easily. For Tomiki, Ueshiba Sensei’s art — which was still Daito-ryu aikijujutsu at that time — included a huge body of essential jujutsu techniques that served as a vital complement to his judo training.

Following completion of his formal education, Tomiki was employed by an electrical company in Sendai. In addition, he entered the prestigious Imperial Martial Arts Tournament (Tenranjiai) in 1929 as the judo representative from Miyagi Prefecture and placed within the top 12 after being forced to withdraw due to an injury.

Tomiki later became a junior high school teacher in his hometown of Kakunodate. While serving in this capacity between 1931-34, he would pass his summer and winter vacations in Tokyo training under Ueshiba Sensei. His sights set on Manchuria then under Japanese rule, Tomiki resigned his teaching post in 1934 and spent the following years in Tokyo in preparation for his move. For a time he rented an apartment near the Kobukan Dojo of Ueshiba Sensei in Wakamatsu-cho and was one of the senior instructors. He also played a major role in preparing the manuscript of the 1933 manual of Ueshiba’s techniques entitled Budo Renshu.

To Manchuria

Tomiki encountered Jigoro Kano for the last time in 1936 prior to relocating to Manchuria. At that meeting Kano encouraged Tomiki to continue his studies of aikijujutsu. Kano himself placed great importance on the preservation of classical Japanese martial arts and held Ueshiba in especially high regard. The judo founder even sent several of his leading students, the best known of whom being Minoru Mochizuki, to train under Ueshiba in 1930.

Relocating to Manchuria in March 1936, Tomiki became a part-time instructor at Daido Gakuin and taught aikibudo to the Kanton Army and the Imperial Household Agency. In the spring of 1938, he was appointed to the staff of the newly established Kenkoku University in what was then Shinkyo (present-day Changchun). This appointment came about due to Tomiki’s connection with Ueshiba’s Kobukan Dojo. As a historical note, Rinjiro Shirata, one of Ueshiba’s best prewar students, was originally selected for the Kenkoku University post, but was forced to bow out following his conscription into the Japanese Imperial Army in 1937.

Tomiki was living in a house in Daiyagai in Shinkyo where he also operated a private dojo. This was in addition to his teaching activities at Kenkoku University. He taught people from the town and commuted to the Military Police Training Hall and the university. Another top prewar student of Ueshiba named Shigemi Yonekawa also lived with Tomiki for a time and assisted him in his teaching duties.

Largely through Tomiki’s efforts, aiki training become a compulsory subject for students of judo and kendo, and therefore he sent for his close associate Hideo Oba, then a 5th dan, from Akita in order to develop a teaching staff. Also, Morihei Ueshiba made regular fall trips to Manchuria during these years also to conduct classes at Kenkoku University. Professor Tomiki made great strides during the Manchuria years in fleshing out his theory of rikaku taisei. This term refers to the use of techniques for dealing with attacks by an opponent separated from the defender. This was part of Tomiki’s view of a “complete judo” which encompassed two parts: “grappling judo” (kumi judo) which equated to Kodokan Judo, and “separated judo” (hanare judo) which was equivalent to aikido.

Ueshiba began to adopt the dan ranking system about this time and promoted Tomiki to 8th dan in 1940. Tomiki was the first person to receive this rank from Ueshiba and this honor reflected the high regard in which he was held by the aikido founder. For the next four years, during the summer months Tomiki would visit Japan where he would give instruction to senior judo dan holders at the Kodokan.

The Waseda years

Following the end of the Second World War, Tomiki was stranded in Manchuria and interned in a prison camp in Siberia along with thousands of other Japanese. He continued developing his theories even while being detained and devised a series of tai sabaki (body shifting) exercises which also served as a means of maintaining his health under difficult conditions. Tomiki was finally released after three years and returned to Japan at the end of 1948.

The next year he left for Tokyo, soon renewing his ties with the Kododan. Later, in June of 1949, he joined the staff of his alma mater Waseda University. In 1951, he became the chief instructor of the Waseda Judo club. In June 1953, together with several high-ranking judo instructors, he journeyed to the United States on a teaching tour that included 15 states during which the delegation from Japan taught U.S. Air Force members judo and aikido.

In 1954, Tomiki became a full professor and head of the Waseda Physical Education Department. At that time there was no Aikido Club at Waseda University, only the “Aikido Circle of the Judo Club.” Since Tomiki taught both judo and aikido, aikido practice was held in the judo dojo when judo practice was not in session. In the same year, he published a book titled Judo Taiso. Tomiki continued experimenting and fine-tuning the theoretical basis for his aikido as director of the judo club during his tenure in the Waseda Physical Education Department.

Another book by Tomiki titled Judo with Aikido — later retitled Judo and Aikido — was published in 1956. Although Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s book Aikido which appeared in 1957 is often considered to be the first book published on the subject, Tomiki’s volume was actually the first to incorporate the word “Aikido” in the title and give serious treatment to the art.

On February 26, 1958, as a result of Tomiki’s efforts, Waseda University approved the creation of an aikido club, one of the conditions being that a method of competition be developed. Together with the members of the aikido club, he devised a form of competitive sparring where an attacker wielding a dagger attempted to score points against a weaponless adversary. It was this action on the part of Tomiki of attempting to convert aikido into a sport that led to a schism with the founder Morihei Ueshiba and the Aikikai around this time. Tomiki was urged by the Aikikai to adopt a different name for his art other than “aikido” if he intended to introduce such a system of competition. Convinced of the need to modernize aikido, he stood his ground and persisted in his efforts to develop a viable form of competition. He did, however, refer to his art in this period as “Shin Aikido.” This same year, 1958, also saw the publication of still another book still in print called Aikido Nyumon.

Professor Tomiki’s theory

Let us pause for a moment to examine Tomiki’s rationale for introducing competition to aikido. As mentioned earlier, Professor Tomiki’s view of the martial arts as a means for edification of the individual was heavily influenced by Professor Kano’s philosophy. On the one hand, Tomiki regarded the traditional martial systems of Japan as feudalistic, brutal and thus unsuited for the modern age. Yet, at the same time, he wished to guarantee the survival in some form of these highly-refined technical traditions that had been developed over hundreds of years. His solution was therefore to modify the classical ryuha eliminating dangerous techniques without, however, losing sight of their historical rationale.

The framework of modern physical education provided the ideal vehicle to accomplish this end. The practice of kata would permit the preservation and transmittal of the classical forms while competition insured that the trainee would gain a practical understanding of the application of offensive and defensive techniques. While the role of sports was significant in Tomiki’s thinking, it formed only a part of his eclectic system. Moreover, he recognized the danger inherent in an over-emphasis on competition that spawned an undesirable “victory above all” attitude in participants.

Another book by Tomiki titled Judo with Aikido — later retitled Judo and Aikido — was published in 1956. Although Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s book Aikido which appeared in 1957 is often considered to be the first book published on the subject, Tomiki’s volume was actually the first to incorporate the word “Aikido” in the title and give serious treatment to the art.

The Continuing Experiment

By 1964, Tomiki had become a senior professor at Waseda University and was in charge of a post-graduate course in physical education. That year he published his Shin Aikido Tekisuto as well.

In 1967, Tomiki opened his Shodokan Dojo which he used as a testing ground for his theories on aikido and competition. In 1970, Tomiki retired from Waseda University and, in the same year, presided over the first All-Japan Student Aikido Tournament. The basic rules for the holding of aikido tournaments had been worked out by this time in what would become an ongoing experiment to develop a viable form of competitive aikido.

From an aikido standpoint it is easy to forget the importance of Tomiki’s judo background in evaluating his approach to aikido. But Tomiki was first and foremost a judoka insofar as concerns his views on modern martial arts and physical education. He regarded the aikijujutsu of Morihei Ueshiba as a wonderful addition to the incomplete technical curriculum of judo. In Tomiki’s view, when these techniques were added to Kano’s judo, it became a complete martial art. Where Tomiki departed from Ueshiba in his thinking was while the aikido founder viewed aikido in religious terms, Tomiki, the academician, saw the art as a means of physical education and self-betterment. In any event, Tomiki’s association with Kodokan Judo continued for more than 50 years and he was awarded 8th dan in 1971.

In 1973, Tomiki lead a group of Japanese martial artists that included one of his top students Tetsuro Nariyama to Taiwan. The contingent from Japan gave demonstrations at military and police academies where they were well received.

Last years

One of the focal points of Tomiki’s latter years was the attempt to solve the difficult problem of how to devise a technical curriculum and set of rules for aikido that would permit the art to take its place among modern Japanese martial arts such as judo, kendo, and karate which included a competitive component. To this end, the Japan Aikido Association (Nihon Aikido Renmei) was established in 1974 with Tomiki as its first president. In 1975, Tomiki, ever active in the promotion of martial arts, was elected Vice-President of the Nippon Budo Gakkai.

Tomiki set up a new dojo for the Shodokan in Osaka on March 28, 1976 with the support of Masaharu Uchiyama, Vice-Chairman of the J.A.A. This dojo was intended to function as the headquarters of the Japan Aikido Association and Tomiki served as its first director.

Tomiki’s final years were devoted mainly to writing, teaching and actively participating in various organizations involved in research on the principles of physical education and Japanese martial arts. He also traveled to Australia in 1977 with his wife and one of his leading students, Fumiaki Shishida. Tomiki’s health began deteriorating in the summer of 1978 and he was forced to undergo an operation for what proved to be colon cancer. Even though gravely ill, he continued to stay active and this writer remembers spending a very pleasant and informative afternoon with him discussing his theories on March 10, 1979. Tomiki breathed his last on December 25, 1979 leaving his closest disciple, Hideo Oba Sensei and the Japan Aikido Association to carry on in his footsteps.

In many respects, Kenji Tomiki can be considered as a “second Jigoro Kano” for his untiring efforts in building upon the work of the judo founder and his novel theories and attempts to modernize aikido by converting it into a sport.

[I am indebted to Professor Fumiaki Shishida of Waseda University and to Tetsuro Nariyama Sensei of the Shodokan Dojo for materials from which I have drawn heavily in writing this overview. I would also like to recognize the late Aikido Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba and Aikikai Shihan Shigenobu Okumura for their many useful insights.]Stanley Pranin

February 2001

Add comment