The following article was prepared with the kind assistance of John Burn of the UK after the passing of Seigo Yamaguchi Sensei.

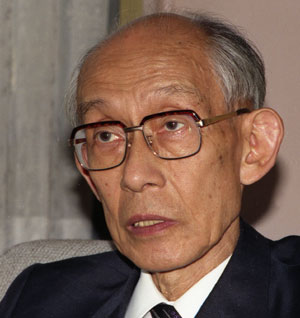

Seigo Yamaguchi—Bio-sketch

April 13, 1924 – born in Fukuoka Prefecture;

October 1943 -departed for the front in the Pacific War;

October 1945 – discharged from service;

1951 – began studying aikido under founder Morihei Ueshiba;

July 1958 – dispatched to teach aikido to the National Defense Forces in Burma;

July 1977 – went to teach aikido in Europe (primarily France) and thereafter taught every year in France (Paris), England (Oxford), and Germany (Manheim) until 1995

January 1992 – received a Distinguished Service Award for his efforts in budo from the Nihon Budo Kyogikai

January 1994 – awarded 9th Dan

January 24, 1996 – died

Eulogies

Aikido Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Yamaguchi Shihan, when I first learned that you had left us, I felt a chill wind sweep through my heart. For a moment all was blank and I trembled deep inside.

The relationship between you and me goes all the way back to 1951. That was the year in which, through your association with Nyoichi Sakurazawa Sensei (known in the West as Georges Ohsawa of Macrobiotic fame), you came to knock at the gate of aikido and began your training under founder Morihei Ueshiba. For over forty years since then you and I have trodden the same path together, training diligently and never resting even for a day.

In 195I Japan was a defeated nation still struggling to wake from a terrible nightmare. Young people had lost much of their vision of the future and their days were filled searching this way and that in hopes of finding a new direction. In the boundless spirit of aikido and the expressive medium of martial arts we saw a bright ray of hope for the future and, seizing it, we vied together and stimulated one another to grow.

There is something resonant in the philosophy of aikido that has led ever-increasing numbers of people to explore it – over a million and a half at present, it is said. These people seek not only to experience the martial technique of aikido, but also to apply its true essence in everyday life, a trend that grows stronger as we move into the new century.

Looking back to when we entrusted our dreams to aikido, I cannot help but feel how far we have come. During that early period, when it was still very difficult to go abroad, you were the pioneer who went to Burma to teach, taking the opportunity to bring aikido out of Japan to manifest its potential in the world. It is well known how hard you worked toward the development of aikido.

Both you and I had strong personalities, yet strangely enough we always ended up seeing eye-to-eye, and our interaction was always cool and composed. Looking back, it occurs to me how fortunate that was. The one point that brought us together, I am sure, was the love of aikido that we shared.

As a fellow traveller along the path of aikido, my long association with you has left a permanent mark on my heart and mind. Your sudden departure represents a turning point in my life and will have a great effect on me.

Happily, your wife Teiko remains in good health, and I have no doubt that your son Tetsu will carry on your spirit and strive to the utmost to realize your ideals. I know, too, that you will be keeping watch over them from heaven.

At the kagami-biraki ceremony this last New Year’s, you told me that my dedication demonstration seemed very natural, very myself and lacking in pretention. It was while this lovely comment was still vivid in my mind that suddenly you were gone, and I will treasure those words.

On behalf of those million and a half people now involved in aikido, I mourn for you from the bottom of my heart. Seigo Yamaguchi Shihan, may your spirit dwell in eternal peace.

January 29, 1996

To Yamaguchi Sensei, who made me want to train in aikido by Seishiro Endo, Aikikai Shihan

Yamaguchi Sensei loved his coffee and tobacco. In his later years he managed to stay away from the coffee well enough, but he was just too fond of the tobacco. He also loved to talk, which he could do for four or five hours at a stretch. Given his quick mind and strict position and views on aikido, I think there were many people who were at their wit’s end with his conversation and simply avoided going with him to his favorite coffee shops. That’s the kind of teacher he was, but for my part, whenever I could spare the time, I always went with him.

Back in my university days I was training under all the teachers at the Hombu Dojo. I knew that they were all very powerful, but I had no way to judge marvelous technique when I encountered it, so I didn’t notice anything special about Yamaguchi Sensei’s training. I listened to all the teachers’ instructions and explanations, but I never thought particularly deeply about them, and I continued to barrel my way through each practice, relying on strength and generally training in my own self-indulgent way.

After about ten years, however, I began to have doubts about my way of training. It also happened that I injured my right shoulder so badly that I couldn’t even get on the mat. One day I happened to meet Yamaguchi Sensei in a coffee shop. He said something to me that turned my aikido around 180 degrees: “You’ve been doing aikido for ten years now, but now you have only your left arm to use, what are you going to do?”

His words had an impact on me, and from then on I made a point of attending his 5:30-6:30 training every Monday. I hardly went to any of the other teachers’ classes. After training under him for a while, I began to realize that there was indeed something different about his technique. My doubts and uncertainties about my own aikido began to dissolve as I realized that I had discovered a new direction.

About this new direction, Yamaguchi Sensei told me, “Even if you don’t understand it, just take my word for it and give it ten years or so…” Ten years seemed a disappointingly long time, but his words also gave me something to hope for. In any case it was an opportunity to make a new start in my training.

During practice, Yamaguchi Sensei would often have me take ukemi for him, while he gave various bits of advice and instruction. This instruction was not meant for me alone, of course, but the specific content of what he said and the way he said it seemed to be tailored for my benefit. As I took ukemi for him, I would do my best to feel what was happening and later I would try to recreate that same feeling in my own practice:

“Go ahead and give your partner your arm and do your technique.”

“Training that relies on muscle dulls the senses and prevents sharp technique.”

“Don’t pin your partner using strength.”

“Even if you don’t understand, just have faith and do it for ten years or so.”

“Focus your strength in your lower abdomen and take it out of your upper body.”

“The more your ki gathers, the more you have to release the strength from your upper body.”

“Techniques must always be concrete.”

“A person who hasn’t developed a degree of competence by their thirties will not progress any further.”

I guess there’s really not much point in listing all the things that Yamaguchi Sensei said, but my eyes used to shine when he turned his enthusiastic talk in my direction, and I used to prick up my ears and listen, trying hard not to miss a single word; I could hardly wait until the next practice.

Many people have told me that it was Yamaguchi Sensei who motivated them to continue training in aikido. He was the kind of teacher who even in his later years never lost his enthusiasm for training. From the beginning of last year there began to be small signs that something was not quite right with his health, and every time I noticed one of these signs I begged to him to go have it checked out, but he always just smiled.

One of the last things I heard Yamaguchi Sensei say was, “O-Sensei said that training with ten thousand different people will make you a master, but don’t forget, training does not mean teaching.”

I have so many strong memories of Yamaguchi Sensei that they would never fit in this limited space, so I will finish by simply offering a prayer of gratitude and hope for his happiness in the next world.

Suikomi by Sunao Hari Kanshu, Aikido/Tai no jo, Kodenkan

I always used to tell people practicing in my dojo, “Yamaguchi Sensei is one of aikido’s real treasures. If you ever have an opportunity to study under him, you should by all means do so,” and I used to add, “while he’s still healthy and active”, thinking that he still had many years to give us. But now Yamaguchi Sensei has left us suddenly.

I began at the Hombu Dojo in 1957. After a while, however, I began to feel that my aikido had reached some sort of an impasse. Disheartened, I figured, “Well this is no good, I may as well just give up.”

It was right about then that Yamaguchi Sensei happened to return from teaching in Burma.

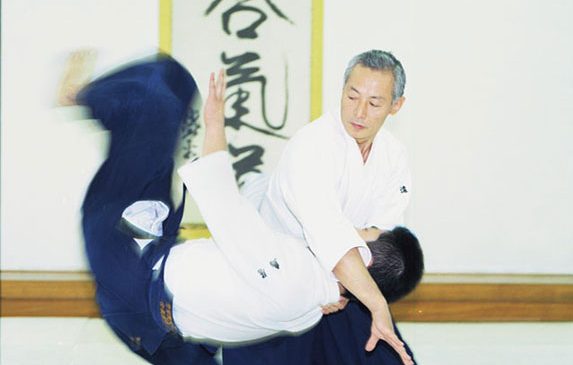

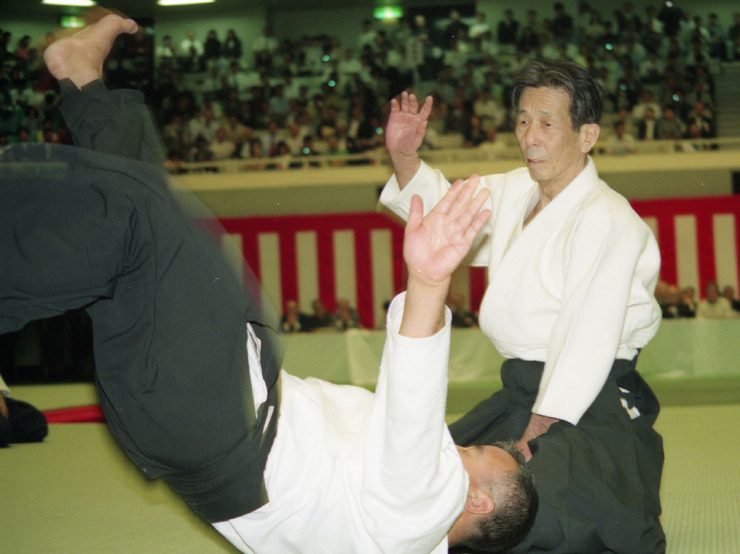

“A willow in the wind, floating, light and air, a feather carried on a breeze”; these are some of the impressions that remain with me from my first experience of training with Yamaguchi Sensei. That training renewed my confidence, for in it I found something at which a person like myself—small-bodied and utterly lacking in physical power—could be successful. After that I trained under Yamaguchi Sensei as much as I could.

Opinions of Yamaguchi Sensei’s training seemed to be split fifty-fifty. In the dojo I heard conversations like, “I hate the way his hands just seem to stick to you so that you can’t really let go,” and, “Really? I think it’s great when that happens.”

I’d be willing to bet the majority of people were Yamaguchi “fans.” For myself, Yamaguchi Sensei was like a guidepost that has enabled me to continue walking the path of aikido for nearly forty years. Of the group of people with whom I sweated back then, many are still active in the forefront of the aikido world.

We had a term that we used among ourselves in training: suikomi, or “drawing in.” This was the word we applied to the way in which Yamaguchi Sensei would draw his partner in at the moment of contact. Seeing how well we could duplicate that effect was one of our main goals during practice.

Getting tossed across the mat felt best when it was Yamaguchi Sensei doing the throwing. He would whoosh you off into space for an instant, then throw you to the mat like a wet cloth. But his techniques were so beautifully done they never really hurt, and in fact they usually felt quite pleasant.

What did give me trouble was his endless talking after training—cup after cup of coffee and an endless chain of cigarettes! I personally was more interested in liquor and doing aikido, so I usually left early. I’d time my escape so that just when Sensei was crushing out his latest cigarette I would jump up and say, “Well, I guess I’ll be off now!” If I missed that window of opportunity, the next cigarette would appear and the talk would go on and on.

Thinking about that now, it occurs to me that although I told people to study under Yamaguchi Sensei as much as possible, I myself perhaps avoided an important part of what he was all about. I realize now that his talking was also part of his very essence as a teacher.

Gassho.

Remembering my Former Teacher by Yoshinori Kono, Martial Arts Training Research Association & Shoseikan Dojo

Seigo Yamaguchi Sensei was someone I truly looked up to as a teacher during my aikido training days. He was also the one who created the opportunity for me to discover the Kashima Shin-ryu, which ultimately led me to apply myself seriously to the pursuit of bujutsu.

Yamaguchi Sensei was perhaps the first person about whom I truly felt a deep respect, from the heart. Still, thinking about it now, I realize that this may in part have been the result of the greenness of youth, idealizing Yamaguchi Sensei in a way that matched my own image of him. From Sensei’s point of view, I may have actually been more of a burden than anything, and I feel obliged to apologize.

My demands on Sensei to be a certain way escalated to a point that the reality would no longer hold with my image, so that, in 1977, for what most people would view as an extremely trivial reason, I suddenly parted company with Yamaguchi Sensei. I remember how the tears welling up in my eyes blurred the lights going past outside as I rode the train home that night.

Having parted with Yamaguchi Sensei for such a selfish reason, and not wanting to cause offence to others, I always felt I would have no right to show my face at his funeral. Still, on the morning of January 24, when I learned Yamaguchi Sensei had died, I experienced a stirring in my heart and a sudden longing to be there to mourn him.

Perhaps guessing my feelings, Mineo Ito, a budo friend of mine for twenty years and also a man deeply trusted by Yamaguchi Sensei, said, “Let’s remember him together.” So, a few days before the funeral, we placed Yamaguchi Sensei’s photo in my dojo, laid an offering of flowers in front of it, and conducted a memorial training session. We talked of our memories of Yamaguchi Sensei until nearly dawn.

Thinking about it now, I also realize that the creation of my Martial Arts Training Research Association and Shoseikan Dojo was, in a way, a desperate attempt on my part to have a place to train after parting from Yamaguchi Sensei.

Later, being fortunate enough to meet such outstanding teachers as the Shimbukan’s Tetsuzan Kuroda and Shindo-ryu karate’s Kenji Ushiro, my technique became quite different from what it was then. Nonetheless, it seems that the influence of those you have respected deeply and who educated you as you took your first steps on the path of bu remains with you. About two years ago someone watching my training said, “You know, looking at your technique I think you must have been greatly influenced by Yamaguchi Sensei. I don’t know exactly what kind of technique you’re using these days, but in many places it looks exactly like Yamaguchi Sensei’s.”

A similar thing happened over ten years ago. An individual who had trained with me for just a short time before going off to school in France told me that when he started training in a French aikido dojo, someone asked him, “While you were in Japan did you learn from Yamaguchi Sensei?”

Of course, all this is probably to be expected. After all, around 1975 I used to go to Yamaguchi Sensei’s private dojo, located between Shimokitazawa and Ikenoue, spend the night there, and then head off to his classes at the Hombu Dojo. That meant I used to spend at least four days out of every week training with Yamaguchi Sensei. While I was by no means one of his closest or favorite students, I wouldn’t be surprised if I took ukemi for him more than anyone else at the time.

Now, however, all that I can do is apologize to him for making such a nuisance of myself and offer my prayers that he rests in peace.

Memories of the Yamaguchi Sensei Salonby Hifumi Nonaka (Miyazaki Prefecture Shibu) Shihan

The more years you put behind you, the more opportunities for sadness you have.

One such sadness is the loss of a sempai from whom you have learned from your sensitive, impressionable youth until the onset of middle-age—no, not just someone you have learned from, but rather with whom you have shared years of glowing memories.

Yamaguchi Sensei has left us. We shall no longer hear his voice.

There are many things that you don’t really think about much until you’ve lost them. Among these are the people with whom you have enjoyed relationships— your seniors or juniors and colleagues in some specific endeavor. Even if there was nothing in particular that you learned from them or that you taught them, the existence of the relationship itself is meaningful. Just having been there is sufficient reason to feel glad. This is something I have been feeling particularly strongly of late.

Of course, for me, Yamaguchi Sensei was not just someone who was “there.” No, if I had not met Yamaguchi Sensei when I did and in the way I did, I would probably not be the person I am today. It was as if I needed to meet him.

Yamaguchi Sensei was in the old Hombu Dojo when the founder was still active and in good health and I myself had just begun aikido. I remember when Tadashi Abe Sensei and Mutsuro Nakazono Sensei had just returned from their overseas teaching assignments and were reporting on their experiences.

Abe Sensei’s report had the atmosphere of a live blade to it, while Nakazono Sensei’s was delivered in an amusing fashion, including stories of some of the girls he had met! Then it was Yamaguchi Sensei’s turn. He had little of the gallantry or dash of the other two, and his slightly worn brown suit and rounded shoulders did not lend him a very strong presence. He delivered his report in a whispery voice that you could barely understand, and I can hardly even remember what he said. But I shall never forget the deep reverence and sincere courtesy of the bow that he made to the founder before returning to his seat.

Still, that was the only impression I had of him at the time, and it was not until later that I really came to admire Yamaguchi Sensei. One evening in the changing room after training, as I listened to the lively chatter of the students, a cheerful voice echoed through the sweaty, slightly moldy-smelling air of the changing room: “No way; that’s no good; don’t you see? Not studying and just trying to get your grades; that won’t do at all!”

The voice belonged to Yamaguchi Sensei, who was teasing one of the students from Meiji University, and at that moment I suddenly felt a kind of closeness towards him as I realized his warmth and approachability.

Back then it was the custom for people who had nothing in particular to do to gather around Yamaguchi Sensei in a coffee shop for an hour or two of lively discussion. I was one of those almost always there. Once, soon after I began attending Sensei’s classes at the Kasumi-cho dojo, I went with him and another one of his students to have some tea. The other fellow excused himself after a while, and it was only later that I heard, from Yamaguchi Sensei’s wife, that he had said, “My goodness, won’t those two ever run out of things to talk about!”

I was always impressed by Sensei’s attitude toward both the founder and Wakasensei (the current Doshu). I suppose you could consider such respect normal in the budo world, in which the handing down of knowledge and skill is respected; but Yamaguchi Sensei’s attitude toward his teacher and his teacher’s lineage was such that it caused me to stop and reflect on my own behaviour more than once. He was extremely careful to preserve the vertical axis that is indispensable in transmitting this kind of art.

Yamaguchi Sensei always seemed delighted whenever he had the chance to walk around the neighborhood with a group of young students or go with them to chat in a coffee shop. I suspect that those were the times he enjoyed the most.

Many different types of young people flocked around him, from those with great ability to habit-ridden blunderers like myself. Several of those individuals went on to discover their own paths and eventually parted company with Yamaguchi Sensei. Among them were Shigeru Kajo and Yoshinori Kono, two gentlemen who I thank for being the first to inform me of Yamaguchi Sensei’s passing. Kajo was one of those who carried Yamaguchi Sensei’s coffin; Kono, for reasons of his own, preferred to refrain from attending the funeral, but held a private memorial in his own dojo.

Add comment