Thirty years ago New Zealander David Lynch entered the Yoshinkan dojo as a live-in student Since then he has practiced a variety of styles under a number of different instructors, including Koichi Tohei Sensei of the Ki no Kenkyukai, Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, and Kenji Shimizu Shihan of Tendo-ryu Aikido. Now he runs an unaffiliated dojo in Auckland, New Zealand, where he pursues his eclectic approach to aikido. This interview is the first part of two. You can read the second part here.

David, you are known in the aikido world for your eclectic background. You have had experiences with a number of well-known teachers and systems and are now operating a dojo in New Zealand. Let’s go back to the beginning; how did you first get involved in aikido?

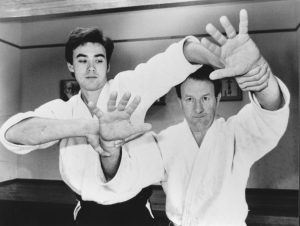

It must have been in 1962, when I came to Japan to work for the Asahi Evening News. I had gotten interested in judo, so I started training and at the same time working and found that I was not well-organized enough to do both. I was either too tired to work or too tired to train. I then found out that it was possible to live in an aikido dojo, although I had no idea what aikido was. I thought, in fact, that judo was sort of the mainstream, and all the others were minor tributaries of it. I learned about aikido from a New Zealand friend of mine, Barney Peihopa. He wanted to send some photographs of himself practicing aikido back to New Zealand, and he wanted a fall guy to take the ukemi. I went along and found that the judo that I had—I was only about nikyu—was quite hopeless in the face of things like nikyo and sankyo, which at the Yoshinkan they called nikajo and sankajo. I thought it was interesting.

Then Barney wanted to get out of the dojo where he was living, so he moved out and I moved in. My entrance test was to be fronted up with [Takashi] Kushida, who was at that time about fifth dan. Old Shioda Sensei was standing there, asking me if I could do ukemi. I foolishly said, “Yes, I can. I can do ukemi.” I didn’t realize what I was in for. He immediately said, “Grab this guy’s wrist.” So I grabbed Kushida’s wrist and it was shihonage, one after another. I realized quickly that I couldn’t do ukemi. I kept landing on my head. I kept jumping up again, and I got so wound up with the whole thing that I was hanging on pretty strong, and he missed a couple of the throws, and that made him even wilder. So I ended up sort of crawling around the mat, not quite sure of where I was. Apparently I had passed the test, so they took me on. I lived in the dojo for about 18 months.

I really enjoyed the simplicity of living in the dojo. You didn’t have to worry about the basics. Theoretically, I was supposed to pay money, and they were supposed to charge me so much and then debit so much for the work, but in actual fact, if you did your job properly it didn’t cost you anything, as long as you stuck to the regime. So we wore dogi and nothing but. I just piled my belongings into the cupboard and didn’t see them again for a bit over a year. We even used to wander around Tokyo, go for a look at Tokyo Tower, wearing geta and dogi.

Shioda Sensei presently limits his activities to giving demonstrations and teaching instructors, but I imagine at that point, in the early ‘60s, he was doing a lot of the daily instruction.

Yes. He was there every day, regardless. This caused me some problems because I had to pick him up for the morning class since I was the only one who had a driving license. I had to get up an hour earlier than the others, and they already had to get up pretty early for the 6:30 morning class. They had a left-hand drive Morris Oxford. Kancho was very proud of this car, with its leather seats, but the engine was absolutely shot. To get it started I had to get up early and pull the choke out and make numerous attempts to start it, and then when I finally got it started I had to let it run for quite a long time. Then I’d have to go and pick him up. He stayed in the dojo one night a week, before the Wednesday morning class, after which we’d mix up this soup with fish and beans, and a lot of the dojo sponsors and some of the older characters used to come.

What was your impression of Shioda Sensei?

Shioda Sensei is usually described as “vigorous” in the various histories of aikido and he certainly was when I was an uchideshi at the Yoshinkan. He is such a tiny man but he used to put on pretty convincing demonstrations. During the weekly training sessions (for selected students) he would egg us on with such intensity it was as if he was possessed. Off the mat I found him a simple man, almost naive, and ready to laugh loudly at anything that struck his fancy.

One of my duties as uchideshi was to scrub his back in the bath! He liked his back soaped and scrubbed hard before he got into the tub. I would sometimes be invited to join him for a soak in the large dojo bath. He told me how he used to do the same for O-Sensei and that he learned his aikido by imitating O-Sensei’s actions in everyday life as well as on the mat, observing precisely how he picked up the soap and so on.

We once had a visit from a Zen master who commented after seeing Shioda Sensei’s demonstration that this was an example of mushin, i.e., “no mind,” the ideal Zen state in which action takes place without being hindered by normal thoughts and fears.

He was a generous sensei to me and was patient with my early language difficulties and moments of culture shock.

At that time, at the Yoshinkan dojo, was there much consciousness of the fact that the man who founded aikido was Morihei Ueshiba?

I don’t think there was. I certainly never picked up on it. O-Sensei was referred to as part of the history of aikido—an important part, of course—but not as the founder. There was more mention of the long history of aikido, stretching back 700 years to Shinra Saburo Yoshimitsu who was supposedly inspired to conceive the art by the movements of a spider making its web. I was told the art came down through the centuries under various different names to the present day. It was not as if aikido suddenly appeared with O-Sensei, even though Shioda Sensei obviously had great respect for O-Sensei. He often told anecdotes about him and I know they got on well together. O-Sensei sometimes telephoned the Yoshinkan to talk to Shioda Sensei, and I recall once going to pick O-Sensei up, in my role as Shioda Sensei’s driver, when the two were going to dinner together. The Yoshinkan operated fairly independently, and when I was training there full-time I never had contact with any other dojo.

I really enjoyed the simplicity of living in the dojo. You didn’t have to worry about the basics. Theoretically, I was supposed to pay money, and they were supposed to charge me so much and then debit so much for the work, but in actual fact, if you did your job properly it didn’t cost you anything, as long as you stuck to the regime. So we wore dogi and nothing but. I just piled my belongings into the cupboard and didn’t see them again for a bit over a year. We even used to wander around Tokyo, go for a look at Tokyo Tower, wearing geta and dogi.

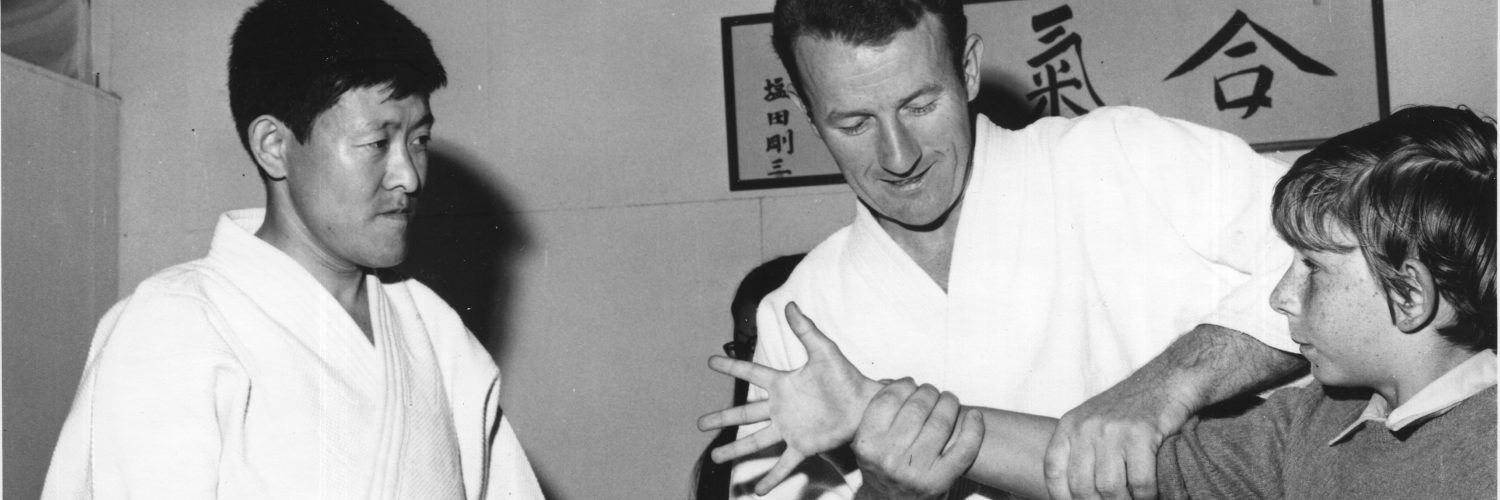

What happened when you went back to New Zealand after you had a few years of training in Japan under your belt?

Well, there was no aikido in New Zealand at that time. Nearby our place there was a sports center and my wife and I started teaching there. It was one of these YMCA-type places, where members paid very little to join, and of course it was voluntary as far as we were concerned. We got more people than we could handle. No one wore dogi or anything, they wore all kinds of strange clothing. I thought if there were that many people, and there were literally hundreds coming in, and going out as well, maybe we could hack it commercially. So with the aid of a friend we took over a warehouse right in the middle of Auckland city and converted it into a dojo and started operating commercially. I quit my job and started full time.

About when was this?

We officially opened in 1967. But we had one major morale problem, because after we had set up this dojo, and did our first ukemi, up from downstairs comes the landlord who happened to be a watchmaker. He said, “Come down here.” I went. I had to admit, it was simply incredible; when someone did ukemi upstairs there was this incredible shaking, and bits of paint from the ceiling fell down, while he was down there trying to fix watches. But I reasoned that he shouldn’t be there at that time of night, because we were doing it in the evening or early in the morning. But after that we had to try and do our training without ukemi or with very soft ukemi. We survived for about a year. We never made any money, but we never lost any money either, so it was even. But with this constant problem with the landlord, we finally moved out. About that time I was in the throes of coming back to Japan, and we closed the professional dojo and went back to a nonprofit organization. Then aiki teachers started drifting in from other places. The first visitor was [Nobuo] Takase. He came over at the invitation of one of the karate clubs, but he fell out with the chap that had sponsored him. I was able to help him reorganize his visa, and then he married a New Zealand girl and he’s been there ever since. Then Frank Holmes came over from England, with a totally new style of aikido as far as we were concerned. It was very soft. Once again it was very demoralizing because we were told that we were doing everything wrong. We were “using too much power;” our aikido was “obsolete.” So, I said to him, “Look, I like what you’re doing. It’s good stuff. Would you care to take over the dojo?” But he wasn’t willing to do that. So we parted company. That was my first real encounter with other types of aikido. I knew that the Yoshinkan would be equally adamant that you did it their way. I guess that was the beginning of the end of my following one particular form. When I came back to Japan, I ended up changing to another style because the Yoshinkan had moved way out of town.

To Koganei?

Yes. I went there for a while, but it was out of the question for me to go regularly.

What year did you return to Japan?

1973.

What brought you back that time?

Basically work. I had this urge to go back to Japan and I suggested to the New Zealand tourist department that they ought to open an office in Japan. This apparently coincided with their own desires, so they virtually wrote the job around me. I applied for it and got it, and came over here to open the New Zealand Government Tourist Office in February 1973. It was supposed to be a three to four year term, but it kept getting extended, so I stayed on here until 1988.

So you were here consecutively for fifteen years?

Yes. During the course of which I ended up going to various different dojos, mainly for geographical reasons. I wasn’t terribly settled in Tokyo at any time and would get fed up with the middle of the city and move out, and then would get fed up with the commuting and come back in. So we moved house about six times in the fifteen years that we were here.

What was your next major training experience in Japan?

I was living in Yoyogi, near our embassy. I heard about the Ki no Kenkyukai, which had just split off from the Aikikai.

This was around 1974?

Yes. The dojo was at the Yoyogi Youth Center, only walking distance from where I was living. It was a very small dojo. They weren’t even using proper tatami. They had wrestling mats.

Do you have any Tohei Sensei anecdotes?

As is well known, Tohei Sensei stresses ki as the main feature of his aikido and does not hesitate to say that other aikido teachers do not do so “because they don’t understand it.” This attitude presents aikido students with a predicament: first there is the demand that you accept that ki is the be-all and end-all of aikido, and then there follows a cosmology based on that which seems to give pat answers to all the problems of the universe, rather in the style of a religious cult. One feels it is all a bit too simple.

The man has a lot of charisma, and seems to convince people in his immediate circle. There’s a lot of suggestibility in people. Take the so-called “unliftable body,” for instance. I had the experience of not being able to lift him up at a time when I was supposed to be lifting him up. He whispered to me, “Psst. This is the warui-ho (bad way).” In the warui-ho you’re supposed to be able to lift him up, but I had actually convinced myself that I couldn’t. There’s no doubt about it, there was a large element of self-suggestion in there.

During the course of which I ended up going to various different dojos, mainly for geographical reasons. I wasn’t terribly settled in Tokyo at any time and would get fed up with the middle of the city and move out, and then would get fed up with the commuting and come back in. So we moved house about six times in the fifteen years that we were here.

Notwithstanding these reservations, I freely admit that I learned a lot from Tohei Sensei and I am very grateful to him for that. His style of teaching may be better suited to Westerners, perhaps as a result of his many teaching trips abroad and the years he spent living and teach-ing in Hawaii. He appeals to rationality, for instance, by having people try to do a technique “the wrong way” (i.e., with excess force) first, and then “the right way” (i.e., by relaxing, extending ki, etc.). I found this helpful in providing feedback on when I was unnecessarily colliding with my partner, and I do believe in the ideal of not using force—though it is easier said than done, and easier to do in a Tohei dojo than elsewhere where your uke may not respond in quite the same obliging way.

However, Tohei Sensei also frequently departs from the rational approach and propounds theories of the universe which are presented as given facts for the students to believe. Though I like many of the principles Tohei Sensei talks about, such as the need to relax and not use force, I have serious doubts about elevating them to the status of Laws of Nature, and about the way in which ki has become a sort of commercialized object for which this particular sensei holds the patent.

Shortly after training with the Ki Society, you had some experience with the Aikikai, is that right?

Yes. It was another change of address and I ended up living in Todoroki and found the Todoroki Dojo just across the road, which was a full branch of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo run by Shimizu Sensei and Watanabe Sensei. They had classes at 6:30 every morning, so it was ideal. I could get there in five minutes. There was no question of politics coming into it at all. It was sheer convenience. I enjoyed that enormously. It was a lovely old dojo, owned by a judo chap. Shimizu Sensei is one of those strong silent types who never abuses his power. We lived there a couple of years and I trained pretty regularly. Then when we moved house again, and for about a year afterwards I carried on going to the Hombu. I went mainly to the morning classes run by Kisshomaru Ueshiba Doshu, so I did not experience the full range of teachers who took the evening classes.

How did you find the Aikikai approach to aikido, having come from Yoshinkan and Ki Society?

I found the training very light compared to Yoshinkan and uninterrupted by long explanations, as in the Ki no Kenkyukai, so that one could get a lot of movement and training done. Also, there were so many students that you had a chance to train with all sorts of different people. Doshu seemed a modest and quiet sensei compared to the others I have mentioned, but I was not that close to him, being just one of 70 or 80 morning trainees.

However, Tohei Sensei also frequently departs from the rational approach and propounds theories of the universe which are presented as given facts for the students to believe. Though I like many of the principles Tohei Sensei talks about, such as the need to relax and not use force, I have serious doubts about elevating them to the status of Laws of Nature, and about the way in which ki has become a sort of commercialized object for which this particular sensei holds the patent.

The Aikikai does not appear to have a “style” as such, and different senseis teach different things. This is good in providing opportunities to train and experience different movements, and no doubt one could get more technical instructions under individual teachers at the evening classes there.

You then had some experience at the Tendokan?

Yes, once again due to moving house. We found ourselves in Meguro within about 15 minutes by motor scooter from the Tendokan. I just noticed the dojo sign, and never had any proper introduction, but I went along and was welcomed into the dojo and enjoyed it a lot. They tend to stick to pretty basic things, which are reasonably credible, and fairly physical. Kenji Shimizu is also a guy who doesn’t abuse his power. I’ve never seen him deliberately hurt anybody or smash anybody up. I went to the morning classes pretty regularly there for the last three years before I left the country.

Do you have any comments about Shimizu Sensei as an individual?

He seemed to me a pretty good compromise between the more military, hard-type Yoshinkan style, which seems to have mellowed out quite a lot since the days when I did it, and the rather loose Hombu style. He maintained quite a good in-between position. He also had lots of anecdotes about O-Sensei. I particularly liked his comment that one should concentrate on discovering aikido “techniques within movement” rather than seeing the techniques as separate things. In other words, if your movement, posture, and attitude on the mat are right you will find opportunities for performing correct technique. Ukemi, staying alert, and balance are all just as important as any individual technique. He was a very nice fellow, and relatively young as aikido senseis go.

All aikido senseis, in my observation, have their human failings, some more obvious than others. I tend to recall these aspects when I am asked about different senseis and sempai, though I realize it is not terribly “loyal” in the traditional sense. However, I am very grateful to all I have studied under and trained with, despite some character flaws one sees in them. Who could not respect the incredible amount of training that these people have had? I am also very conscious of the limits of my own understanding. I regard myself as an “instructor,” rather than a teacher, and if I criticize others I do so without disrespect. At the same time—and I am not aiming at any particular person here—I feel the tendency to elevate a sensei to a “god-like” position is potentially corrupting and can easily result in the “sensei” adopting an arrogance that, to me, obviously contradicts the essential aims of the art. Respect is one thing but that should not mean either grovelling or adulation. So many senseis are tarred with either incredible arrogance or an urge to build an empire at the expense of others. It seems to be getting a bit away from what aikido is supposed to be about. I have no exclusive affiliations with any Japanese dojo, though I believe I am on friendly terms with them.

How do you explain this situation to people who come to your dojo?

In the first place, I tell my students that there are many faces of aikido arising from the different personalities of the main senseis in Japan, as well as from the various different eras in which they all learned from O-Sensei. I stress the need for an open mind and for them to pick up whatever has a meaning for them from the blend of different styles that I teach. Aikido is supposed to be a way to reconcile people, so it should not be hard to reconcile different approaches to teaching the art.

I simply do not buy the theory that there is some loss of integrity involved in studying from more than one teacher or in attempting to learn more than one “style.” If this were so, what would we say about O-Sensei himself who learned from so many different teachers before he developed aikido? Loyalty is one thing, but one must watch out for the negative side. No real teaching can be the private property of any one teacher. It should be universally valid.

I understand that in your dojo you have no rank structure.

None whatsoever. We start everyone in hakama, which the Tendokan does as well. It gives an atmosphere of aikido, as distinct from people running around in their underwear, as O-Sensei apparently called it. So far we haven’t had a problem, although we’ve only been going for two years. There’s a potential problem of somebody hurting somebody through not knowing what their grade is, but I don’t really think that is likely because it’s a relatively small dojo and we all know each other. I reckon if you have advanced at all in aikido you should be suitably sensitive to know whether the person you’re training with is capable of taking certain techniques or not.

We often hear stories or have had direct experiences with individuals who seem to show a lack of restraint when applying techniques, and as a result injure people. I’m not referring to the occasional injury that will happen in the midst of intensive training, but rather people who acquire reputations as body busters. What’s your attitude not only toward that kind of individual but also toward the head of the dojo in which that individual resides and operates?

It seems to happen in Japan. I’ve seen abuses going on on the mat that you would have thought the head of the dojo would have stepped in to stop, but they’ve blithely walked past and let it carry on. I’m totally opposed to such an attitude. You cooperate in aikido; it’s not a competition. You hand your arm over to someone on the assumption that they’re not going to break it off. Otherwise, why give it to them in the first place? There’s an element of trust.

I simply do not buy the theory that there is some loss of integrity involved in studying from more than one teacher or in attempting to learn more than one “style.” If this were so, what would we say about O-Sensei himself who learned from so many different teachers before he developed aikido? Loyalty is one thing, but one must watch out for the negative side. No real teaching can be the private property of any one teacher. It should be universally valid.

These people are often very strong, but you don’t have to be particularly strong or skilled to do this, all you have to have is the will.

It’s just not fair at all, because a person who has built up a few years of training is obviously in a position to do serious damage to someone. I can’t see how some people can justify this kind of training in the name of aikido.

I’ve heard attempts at justification, and they run something along these lines. Aikido is a martial art. If you are training in a martial art you’ve got to train seriously and with intent, and sometimes when you’re training at that level accidents happen. This is part of the risk that you accept to become strong and to learn true budo.

And that uke’s failure to have sufficient ukemi is the problem, not the person that does it. That seems to be wide open to abuse.

David Lynch Profile

Born in 1939. Yoshinkan Aikido 6th dan, Aikikai 3rd dan, Tendo-ryu Aikido 3rd dan, Shinshin Toitsu Aikido 2nd dan. Consultant. Began training at the Yoshinkan Dojo under Gozo Shioda as an uchideshi in 1962. Spent a total of 18 years in Japan. Operates a private dojo in Auckland New Zealand with wife, Hisae Lynch (3rd dan). The Lynch Dojo, 25 Lewin RoadOne Tree Hill, Auckland 3 New Zealand.

This interview is the first part of two. You can read the second part here.

Add comment