The following translation from the Japanese-language autobiography entitled Aikido Jinsei (An Aikido Life) by Gozo Shioda Sensei of Yoshinkan Aikido is published with the kind permission of the author and the publisher, Takeuchi Shoten Shinsha. The series began with AIKI NEWS No. 72. Read the fourteenth part here.

Goza Shioda settles into his new life in Pontianak, Borneo and surrounds himself with animals and luxuries. His local reputation rises even higher when he starts teaching aikido to members of the Special Police Force.

The Shioda Zoo

I naturally love animals so much that I bought nine monkeys in Macassar and Surabaya and brought them to Pontianak. After I came to Borneo, I kept three young orangutans. In addition, my family included nine dogs, about 40 ducks and domestic fowls, eight geese, a Bornean deer that weighed about 150 pounds, and two long-armed apes. Because I had so many animals my business colleagues in Pontianak called my house the Shioda Zoo. In particular, one young orangutan named Saburo, was my most favorite friend. He used to accompany me wherever I went, to bed, to work, and even to the movies. Whenever he came to my bed, he used to clean his feet with a dust cloth and crawl in under the mosquito net, securing it behind him to prevent mosquitoes from getting in, and then he would lie down beside me. When I would comb my hair and get ready to go out he would also eagerly comb his hair in front of the mirror, imitating me. I had two sets of clothes made for him, a morning dress for outings, and a set of everyday wear. Whenever we went out, he used to ask me to dress him in his morning suit by bringing it to me. He was a really cute ape. The primary mode of transportation there was bicycle. When he saw me ride my bicycle, he used to bring my bag to me and ride along in front of me. When I watched a movie if I laughed at a funny scene, he used to express his pleasure too with his whole body, flapping his hands and feet. Sometimes I felt as if he was a human child.

Since that event, I taught them aikido every day, and I spent more time teaching aikido than working for my company. However, I think the fact that I was teaching aikido was contributing greatly to my company, and also in a broader sense both materially and immaterially to my country. The reason is this. At that time, the trading companies that fell under the Navy’s jurisdiction were assigned to contribute to the victory of Japan, without taking their own interests into account. The profit of the nation took absolute precedence over the companies. In this way, I am sure that my instructing aikido was very useful to the company as well as to Japan.

This was the nature of my everyday life. To add some variety to my monotonous existence, I ordered many different kinds of goods, such as shoes made from alligator skins, an alligator bag with a clasp of pure gold, and a gold lighter with a dragon with inlaid diamond eyes engraved on it. Anyway, it was quite absurd. I had 40 suits, 21 pairs of shoes, 15 wristwatches, etc. I think it was both the first and last time that I ever experienced such glorious days. At that time I was 28 years old and was energetic, in high spirits, enjoying a full life in both mind and body.

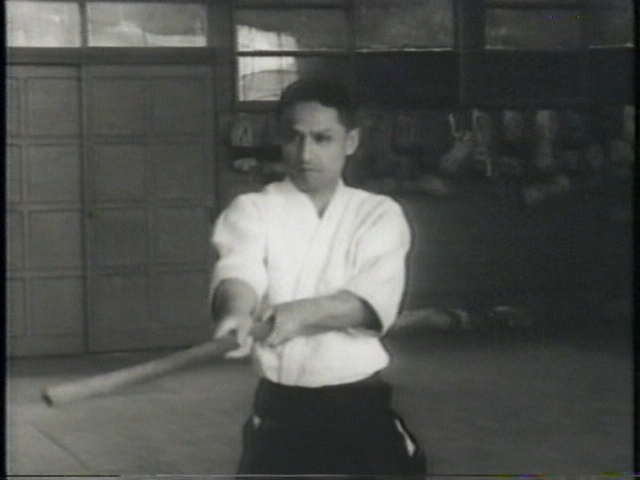

Mr. Shigeeda used to come to my house almost every day and we would have a pleasant chat. One day he said, “You are splendid in aikido. Would you be willing to teach it to the Naval Tokkei?” The Naval Tokkei was the equivalent of the Army’s Military Police in function, and the nickname was an abbreviation of Tokubetsu Keisatsutai (Special Police Force), its formal Japanese name. The force was responsible for maintenance of public peace and law and order in the districts under its supervision. Primarily, the regular duty of the Tokkei seemed to be to supervise Japanese commercial firms, but since the Civil Administration’s police could not supervise the members of the Navy, the Tokkei did so. Therefore, it was a very influential organization. I was introduced to Lieutenant Yamamoto, a leader of the Tokkei by Mr. Shigeeda, and it was immediately decided that I would teach aikido to the Tokkei. There were eight members of the Tokkei, and they all had been carefully selected. Therefore, it was natural that they were all powerful and strong-willed, typical military men. At first they did not want to believe in aikido techniques. So I asked them, “Who is the strongest?” They replied, “Mr. T is a 3rd dan in judo, and 3rd dan in sumo; he is the strongest in the Tokkei.” Then I said to him, “Please attack me any way you like.” He stared at me angrily. It was only natural for him to be angry. A brave man with a 3rd dan in judo and sumo like him might feel that he had been insulted when such a thing was said to him by such an uncommonly small man as myself. I remember my state of mind at that time. It was as calm and serene as reflecting water, and peaceful. At least I did not feel unsettled. I think it was the self-confidence I gained from my experience with actual fighting in Shanghai that made be feel that way, although I was not aware of it. As soon as he stepped towards me aggressively, he jumped and tried to attack my hips. I immediately dodged and attacked him with a slight atemi to his hips. He staggered to the ground and unexpectedly admitted his defeat to me.

Teaching Aikido

Since that event, I taught them aikido every day, and I spent more time teaching aikido than working for my company. However, I think the fact that I was teaching aikido was contributing greatly to my company, and also in a broader sense both materially and immaterially to my country. The reason is this. At that time, the trading companies that fell under the Navy’s jurisdiction were assigned to contribute to the victory of Japan, without taking their own interests into account. The profit of the nation took absolute precedence over the companies. In this way, I am sure that my instructing aikido was very useful to the company as well as to Japan. I am convinced that no one could have done just as I did, no matter how able a businessman he was. I was devoting my youthful enthusiasm to my country and also to my company through aikido, and I was very proud of that. I made it a rule to train the students of the Tokkei in the morning, and both Mr. Shigeeda and Mr. Masaki starting at 4 p.m.

At that time most Japanese businessmen were on intimate terms with native women, and they would keep the women as their temporary wives. Virgin native women cost about 30. It is said, “The cause of a crime is always a woman,” and company secrets were often revealed in talk in bed. To prevent that, the director of the Tokkei said to me, “Shioda, I guess you must have a good inside knowledge of businessmen because you are a businessman too. Would you please make a list of men who are keeping women and let me know about it?” I though I was paid as a part-time employee of the Tokkei, I could not accept his request, and never reported to him. I would have felt as if I were being controlled by my position, and this made me feel very ill at ease.

A Quarrel With President Omori

One day, Kagawa reported to me that he needed to buy a motor for the equipment to automatically generate electricity on Tordipil Island. Surprisingly, the cost was 160,000. The entire budget for Taiwan Tanning was 200,000, so if we were to buy that motor, the balance would be only 40,000. Kagawa said that he preferred to ask me rather than President Omori, because he was certain that Omori would refuse his request. Although it was not easy to make up my mind, I finally decided to approve his scheme, and said to myself, “Hit or miss, I’ll give it a try.” I told him I would go to the Taiwan Bank to borrow money, and went to the Pontianak Branch. I met with the president of the branch and asked him to loan me 160,000. He approved my request on the condition that later I report this loan to the head office of the Taiwan Colonization Company. Kagawa was very pleased to hear this and on our return we made arrangements to buy the generator. When it was delivered to the office, we discovered that it was quite large and weighed over two tons. It would be a hard task to deliver it to Tordipil Island. Because we could not just load it on a motorboat, we had to have it delivered by a large ship. While we were busying arranging for the equipment, President Omori returned to the office after a long absence. When he heard my explanation of Kagawa’s plan to provide the motor to Tordipil Island, he went red with anger and blamed me because I had managed the accounting without his permission. He scolded me severely. Omori then immediately went to the Taiwan Bank to see the director of the branch and demanded that he not approve loans unless the request was accompanied by an application that he had signed. However, the director retorted strongly, and said, “I have received from your head office an order to lend money to the secretary Mr. Shioda upon official application. If you would like to have me do otherwise, please show me an official document from the head office of your company. After I have received such a document, I will follow your order.” He protested so vigorously that Omori seemed bewildered. Omori had rarely been to the city and never attended meetings held by the city council. So he was not particularly favored by the citizens. I, on the contrary, had attended all the meetings on his behalf. I was better known to the people of Pontianak than he was. Also the director knew well that I was teaching aikido to the Civil Administration and to the Tokkei, and he seemed to respect me and feel friendly towards me. In addition to that, Omori complained so forcefully to the director that he may have produced an unfavorable impression. I suppose that harsh words for harsh words led to such a consequence.

Then I said to him, “Please attack me any way you like.” He stared at me angrily. It was only natural for him to be angry. A brave man with a 3rd dan in judo and sumo like him might feel that he had been insulted when such a thing was said to him by such an uncommonly small man as myself. I remember my state of mind at that time. It was as calm and serene as reflecting water, and peaceful. At least I did not feel unsettled. I think it was the self-confidence I gained from my experience with actual fighting in Shanghai that made be feel that way, although I was not aware of it. As soon as he stepped towards me aggressively, he jumped and tried to attack my hips. I immediately dodged and attacked him with a slight atemi to his hips. He staggered to the ground and unexpectedly admitted his defeat to me.

In the middle of October a sealed letter was delivered to me through the South Marine Transport Company. It contained copies of two telegrams, one sent to the head office by Omori and the other their reply, about which I had known nothing. These telegrams said, “I (President Omori) want to replace directors Shioda and Kagawa, who are both extremely wicked. Please send us two new directors as soon as possible.” The head office replied “We cannot afford to do so at present, so continue your duty and encourage both of them.” When I found out about this, my state of mind was not peaceful. I showed these messages to Kagawa. He, as I had expected, got very angry about it. “How could he call us wicked?” he asked. “Mr. Shioda, let’s go after the persons concerned. Under the circumstances we should cut them with blows.” He seemed as if he were going to get violent at any moment. So I soothed him and said, “Be calm. First, I’ll protest to him, and if this is not effective, then you may do as you like.” He agreed to wait.

When I left Japan, I had made up my mind to commit seppuku with good grace should it become necessary, and had brought a white kimono and cotton hakama with me [the clothing traditionally worn for seppuku]. I put them on and tied a towel around my head and went to Omori’s house after midnight. He was surprised to see my strange appearance, and asked, “Mr. Shioda, why are you wearing such an outfit?” “You know the reason,” I replied, and showed him the copies of the telegrams. When he saw them he turned pale. “Mr. Omori you never told me directly that I was wrong, and you never advised me, either. Instead you took this cowardly action and told tales to the head office and planned to replace us. Why did you do such a thing? I think it is not a manly thing to do. We are now in a foreign country where a battle is being fought. Why can’t you behave fairly? Mr. Kagawa and I will work to the best of our abilities, and we will never be afraid of death in the line of duty, if you give us your support. I think we both have a strong sense of responsibility, but you consider us to be ‘wicked.’ It sounds as if we were criminals. We have never behaved like criminals. You should reconsider this matter carefully. We are calling you to account,” I told him sternly. He sank to his knees and begged my pardon, saying that he was wrong. He promised to immediately send a telegram in reply to the head office saying that he would follow the office’s orders and encourage us to do our best. The day after that he went to the mountains again as if he were running away. When I told the details of this conversation to Kagawa, he regretted very much that he had not accompanied me.

Add comment