1. Morihei Ueshiba made no attempt to ‘teach’ the knowledge and skills he possessed to his deshi;

1. Morihei Ueshiba made no attempt to ‘teach’ the knowledge and skills he possessed to his deshi;

2. The latter all gained profound knowledge and skills during their time as deshi, but it is by no means clear that they gained all the knowledge or that all gained the same knowledge.

3. Morihei Ueshiba appears to have made no specific attempt to check whether his deshi had understood what they had learned from him.

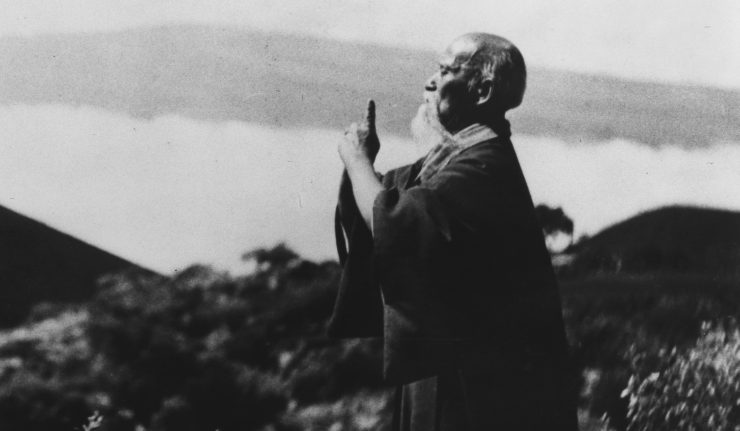

In the last column I considered the first of the above three propositions from the viewpoint of Morihei Ueshiba as a teacher and discussed the question of how, as a Japanese living in the Taisho & early Showa periods, he would have seen this role. Morihei Ueshiba was not only a teacher, or master, but was also the Source of aikido and constantly refined himself as the Source. (Here we can disregard for the time being the crucial importance of his inheritance from Sokaku Takeda and Daito-ryu, except to note in passing the ways in which Ueshiba distanced himself from Takeda and modified this inheritance. We can also disregard the differences between Morihei Ueshiba and Judo Founder Jigoro Kano, who, like Takeda, was also a Source, but in a less technical sense.) In particular, I drew a sharp distinction between (a) the Master as a Learner, striving to increase his own understanding or possession of the art he is creating, and (b) the Master as a Teacher, or transmitter to others of the art, whether considered as the ‘public’ expression of an individual’s evolving ‘private’ training, or considered as something like an end-product, fashioned into a recognizable art and called aikido.

One could argue that learning and teaching are not so separate and note that many young aikidoists have observed that it was not until they began to teach the art that they actually understood more deeply what they were doing. This might be true, but underlying this observation there seems to be a ‘western’ notion of teaching, with the provision of structured explanations and syllabuses, etc. The observation would thus mean that learning the art in depth entails the quite separate activity of teaching the art to others. Clearly, underlying the observation is also an assumption that teaching is not a mirror image of learning, but a completely different activity, with its own internal principles and strategies. However, the examples of engineering, medicine, languages and philosophy, considered in the previous column, show that in Japan, at least, it is not at all intuitively obvious that acquiring an understanding of an art entails actually having to teach that art to others.

I believe that for Morihei Ueshiba, certainly, teaching and learning were not so easily separated, but this is not because he thought the two activities were different. I think it is rather because he did, in fact, follow the traditional Japanese model and regard teaching and learning as mirror images of each other, as two sides of the same coin. Ueshiba regarded training as ‘doing’ the art—of course, correctly—but he also saw the practice of teaching the art, if he actually ‘saw’ it distinctly at all, as another kind of ‘doing’, namely, being a living pedagogical model to his deshi (hence the meaning of the Japanese term shihan). Thus, he might have modified George Bernard Shaw’s famous diction from, “Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach,” to, “Those who can, do; those who do, teach.”

I think that the two poles of the distinction made in the previous paragraph will appear again and again, as we consider Morihei Ueshiba from the viewpoint of his deshi. (Note on the meaning of terms: In what follows I use the terms deshi, uchi-deshi soto-deshi, kayoi-deshi fairly interchangeably. A deshi is a committed student of the art; an uchi-deshi manifests this commitment more obviously, 24 hours a day, by actually living with the Master; a soto-deshi does this, but does not actually live inside the Master’s house; a kayoi-deshi also does this, but travels to the Master’s house each day. The object here is to focus on the Master as constant model of training and on the students as learning 24 hours a day. Of course, it is a deep commitment for both the Master and his student(s). In the interviews an important distinction is sometimes made between those who were uchi-deshi and those who were not and the actual status of Morihei Ueshiba’s students as deshi—whether uchi deshi, soto deshi, or kayoi deshi—is still the occasion of sometimes acrimonious disputes.) Essential material here is the collection of interviews published over the years by Stanley Pranin. These were published in 1990 & 1995 in Japanese, as 『植芝盛平と合気道』 and 『続植芝盛平と合気道』 and a two-volume revised edition was published in 2006. A selection of the interviews with the prewar deshi appeared in English as Aikido Masters: Prewar students of Morihei Ueshiba, first published in 1993 and one of the most important books on aikido ever to appear in English. This was revised and published in 2010 as Aikido Pioneers—Prewar Era. All the interviews with prewar and postwar deshi are scattered through the Aiki News and Aikido Journal magazine and the associated website, but the value of having them all published together is that one can more easily see the vast difference in approach, attitudes and accomplishments.

(For this AikiWeb column I have confined myself to the English version, Aikido Masters, from which I have taken the liberty of quoting extensively. This English version records fewer interviews and is thus more limited in scope than the two-volume Japanese edition, but it is more easily accessible to aikidoists outside Japan and to aikidoists anywhere who cannot read Japanese. I should point out that there are some interesting differences between this translation and the Japanese originals, but these differences do not diminish the crucial importance of Stanley Pranin’s pioneering work, which the ravages of time will actually ensure can never be repeated. It is thus essential to study these interviews and those who can read Japanese should study the Japanese originals, for there are nuances of language there that the English translation cannot capture.

There is one other point that I should make and this is about the limitations of the interview as a form. I want to stress that this point is not intended to diminish in any way Stanley Pranin’s achievements. Mr Pranin’s interviews allow the interviewees to speak freely about their experiences, but it is not immediately possible to verify the truth of the statements made. So, like G R Grice in his philosophical models of conversation, we have to assume the good faith of both interviewer and interviewee. Of course, like Grice, we assume that no one will willingly tell untruths, but we also have to assume that the truth might occasionally be slanted according to the unexpressed intentions of both. I think that this is hard thing to state, but I also think that it needs to be stated. Given this limitation, of course, the interviews have produced much detailed information about how the Kobukan uchi-deshi viewed Morihei Ueshiba and aikido training.)

b. The latter all gained profound knowledge and skills from their time as deshi, but it is by no means clear whether they gained all the knowledge or all gained the same knowledge.

In view of the vast amount of data yielded by Stanley Pranin’s research, this proposition should not cause any surprise, but I think that there are some important consequences for aikido, considered as an art.

The Life of a Deshi

The first point to note is that many of the prewar uchi-deshi brought to their respective encounters with Morihei Ueshiba as deshi substantial experience in other Japanese martial arts. They acquired this experience either before they became deshi, or during the time they were deshi, or both. Some, of course, were too young when they became deshi to have had much actual experience beyond taking break-falls in judo, but this inexperience was balanced by the relative expertise of others in ken-jutsu and traditional jujutsu. They joined the dojo and trained—and the experience of the experienced rubbed off on the less experienced.

Gozo Shioda (Aikido Masters, p.174—in this column, except where indicated, all subsequent references in brackets are to this book) notes that he had early doubts about the effectiveness of aikido:

“When I saw what O Sensei was doing, I doubted whether he was truly strong. Since I was his student, I was always being thrown. I didn’t think he was strong and thought there must be more to aikido than this.”

However, Shioda’s response was not to try to test Morihei Ueshiba during training, which one might have expected, given the training ethos of the time, but to learn some jujutsu and bo-jutsu—at another dojo. He went to dojo of Takaji Shimizu, the 25th headmaster of Shindo Muso-ryu jojutsu, who also had expertise with other weapons. Shioda adds that he gained confidence in the effectiveness of aikido by throwing Shimizu, with ‘kokyu‘ power, rather than jujutsu.

Thus the deshi brought to their separate encounters with Morihei Ueshiba a wide variety of background knowledge, skills, and attitudes about the martial arts. In these separate encounters a double process was going on: (1) the deshi were trying to grasp what Ueshiba was himself doing and how it was different from what they had learned previously, and (2) where there was a group of deshi, the deshi were working this out in company with their fellow deshi. Even so, the interviews yield a fair measure of bewilderment, in terms of the waza that Morihei Ueshiba showed his deshi and the explanations he gave. In some sense Ueshiba combined being something other, which they could aim at but not reach, with being an essential conduit for their own training. He was the mirror—Shioda sometimes felt as if Ueshiba was also like the kami behind the mirror—and as such the means for them to develop and polish their own reflections in this mirror.

The second point is that the inevitable conclusion to be drawn is that the technical, intellectual and spiritual outcomes, also, varied from deshi to deshi, in terms of knowledge and skill acquired. These must still have been far beyond the attainments of the non-deshi, as the life sketched by Shigemi Yonekawa suggests (p.123):

“The life then was pretty strict. In the morning there was practice from six till seven and again from nine till eleven. In the afternoon we practiced from two till four and in the evening from seven till eight—four times a day (= six hours daily). It was tough. I was puffing and panting all day. You couldn’t get instruction from Sensei when you first joined. It was a severe teaching method. What’s more, Sensei would always look at you with his piercing eyes. It always made me afraid. One time, I took a bad fall or something and Sensei bawled me out right in the middle of the dojo. He stopped the training, even though a great many people had come, and went back to his room. I was left there wondering what had happened and wondering if I would be expelled from the dojo.

“Another thing Ueshiba Sensei would always stress was how you must not become careless or allow any openings. This was how the samurai of old lived. They were taught that they must maintain a mental attitude which would enable them to deal with an enemy whenever he might appear. This was the way it was in Ueshiba Sensei’s daily life, even when he was eating or sleeping. For example, even when walking down the hall, someone might come from any direction. You can’t be careless. Even when talking on the telephone, when someone comes up behind you, you have to have eyes in the back of your head, so you won’t be caught in an awkward situation. This is how he taught us.”

So the deshi trained together and with non-deshi during the official times of practice and then trained again outside these official times, trying to master the actual waza that Ueshiba had showed them and to find ways of conceptualizing for themselves what, exactly, he had been doing. The ideal of 24-hour vigilance against attacks is similar to the monastic ideal of 24-hour vigilance against the ‘wiles of Satan’, espoused by St Basil, St Benedict and others, except that the ideal of the deshi is not exclusively a ‘moral’ awareness. It is the kind of constant awareness that Ueshiba mentions in Budo / Budo Renshu when discussing how to deal with attacks from behind.

The third point is that none of the prewar deshi ever considered that they were anywhere near the level of skill attained by Morihei Ueshiba. Gozo Shioda talks of Ueshiba being possessed by the kami and one of the most poignant points in the interview with Shigemi Yonekawa is that he appears to have given up training because of a huge ‘mental’ block, which he explains on p.143-144:

“I believe that it was in December 1936 that I left the dojo. I went to Manchuria because I had some doubts about aiki-budo. By doubts I mean that I somehow could not grasp the essence of the art and felt a little confused. My doubts had to do with the technical and spiritual aspects. I was bewildered about what I could do to progress a little more. I had run up against a wall. I think everyone has that kind of experience sometime.”

An interesting point here is that Shigemi Yonekawa left the Kobukan for ‘family’ reasons and went to Manchuria, but this was clearly a tatemae. Yonekawa agrees with Stanley Pranin that leaving the Kobukan was not because he doubted Morihei Ueshiba’s waza:

“There was a mysterious, infinite power in what Ueshiba Sensei had, although power is a misleading term. There are various levels among human beings. Ueshiba Sensei’s level was different. He had a kind of power which naturally caused one to bow his head when standing before him. How do you develop this kind of thing? I did not understand this level of training.”

This is the judgment of the man who appears as uke in the Noma Dojo photograph archive. Shigemi Yonekawa entered the Kobukan Dojo in 1932 and left in 1936. So he trained for less than the time it takes an average aikidoist nowadays to obtain shodan. However, his training appears to have been anything but average and he was brilliant enough to be uke for the Noma photographs, but he left because he felt there he had no productive idea of progression in his training, such as would enable him to take the steps required to become anything like O Sensei.

Though this is perhaps not so relevant in a discussion about learning strategies, it should also be noted here that there is nothing in Shigemi Yonekawa’s interview to suggest that Morihei Ueshiba was either aware of his concerns or took any steps to alleviate his pain. Yonekawa left for ‘family reasons’ and that was that. I think we need to ponder this fact at some length.

The fourth point, which ties in with the second point, above, is that scattered throughout the interviews are references to non-deshi training in the Kobukan and other places visited by Morihei Ueshiba. In fact, the only training exclusively for deshi seems to have been the Omoto-kyo training in Takeda. Much is stated about the severe requirements for training at the Ueshiba dojo (two eminent sponsors and/or the permission of Admiral Takeshita) and much is stated about the severe training of an uchi-deshi, but nothing is stated about the requirements for the non-deshi. Nothing is stated about the training of these non-deshi, except that the deshi themselves usually taught them. Were they meant to maintain a constant 24-hour vigilance against attacks from behind? If not, what was the actual content of ‘aiki-budo lite’, as practiced in the Kobukan Dojo? Unfortunately, there are no interviews with the ordinary Omoto believers, or the soldiers who saw Morihei Ueshiba training at the various military schools where he taught. All we have are the interviews of the deshi themselves and we might assume that the training of the hoi polloi was ‘similar but less intense’ than the training of the deshi. I will return to this question, which is fundamental to aikido training as we now conceive it, in later columns.

One conclusion we may draw from these interviews is that, on the basis of these interviews themselves, it is too early to conclude that the training of the early Kobukan years was a seamless garment, understood, as we like to believe nowadays, as ‘something like an end-product, fashioned into a recognizable art’. I think that because of the extremely personal aspects of the master-deshi relationship, the tendency to ‘fragmentation’ was built in right from the very beginning, and was a consequence of the very architecture of the encounters between Morihei Ueshiba and his deshi. The fact that aikido did somehow continue as a garment with very few seams—in comparison with some other martial arts, was due to other factors entirely. This is another major issue to which I will return in later columns

Learning as an Art

A very striking feature of the Aikido Masters interviews, in my opinion, is the complete absence of discussion of any explicit learning strategies on the part of the deshi. There is a little discussion of how Morihei Ueshiba actually structured—or, rather, did not structure—a class, but no discussion of how the deshi themselves made sense of what Ueshiba was showing them. In the first column of this series I suggested a plausible learning ‘paradigm’:

- Aikido is a budo that can be fully taught and fully learned (in the sense that it is possible for the deshi to acquire all of the master’s skills).

- Aikido is a budo that has to be taught and learned by means of being systematized into teaching and learning strategies.

- Whereas the teacher is crucially important in this process, it is the mastery of the teaching and learning strategies on the part of the student that will ultimately determine whether the knowledge and skills can be or have been or are being acquired.

This paradigm would be taken for granted in a western pedagogical context, as suggested in an earlier paragraph, but when applied to the deshi of Morihei Ueshiba, there is very little evidence from the interviews that the deshi actually thought in these terms. For example, in answer to a question about his views on teaching, Noriaki Inoue gives a lengthy discourse on the pure quality of training, involving sweat and rice (pp.36-37). Shigemi Yonekawa (pp. 124-125) is more forthcoming and certainly sees teaching and learning as connected. Mr Yonekawa cites an old Japanese proverb, ‘Teaching is half of learning’, and goes on to explain it, but not in the way we would expect. His explanation is that teaching someone entails correctly mastering the material ‘in the head’ and ‘in the body’. Otherwise one cannot teach it. Thus, the deshi lacked confidence when attempting to teach ‘outsiders’ (non-deshi) what they had learned from Morihei Ueshiba, but this due to a lack of complete mastery of the waza, rather than a lack of explicit teaching strategies, for there were no teaching strategies apart from constant repetition of the waza.

With the benefit of hindsight we might consider it unfortunate that Stanley Pranin did not press further and ask Mr Yonekawa to explain more precisely what mastering the material ‘in the head’ and ‘in the body’ actually consisted in. (For those who read Japanese, the text is on p.115 and 116 of Volume I of 『植芝盛平と合気道』: “「教えることは学ぶことの半ばである」という言葉がありますが、人に教えるということは、つまり、正確に頭の中、正確に体の中に入っていないと教えられないものです。” The English translation (Aikido Masters, p.124) reads: ‘There is a Japanese saying that “Teaching is half of learning.” You cannot accomplish half of learning or teach people if you haven’t mastered the material mentally and physically.’ Note that the correct mastery of the material here is mastery by the teacher, not by the student. Note also that the teaching strategy, such as it was, appears to have been: if you do not understand what Sensei showed or said, repeat what you think he showed, but as ‘intensely’ as possible.

I think that there is a fundamental issue here and this relates to the recent discussions on Aikiweb about ‘internal’ training. I think that the issue relates to the metaphors which you use to conceptualize your personal training and make it meaningful to you as an individual. The issue involves both the strategies used to master the waza, or kata, and the strategies used to master the ‘hidden’ aspects, such as Mr Akuzawa displays when he simply ‘absorbs’ punches and then sends the power right back ‘through’ his attacker. Noriaki Inoue mentions an episode involving Mitsujiro Ishii, of the Asahi newspaper company, who was 6th dan in judo (p.33-34):

“One day, I found him deep in thought. When I asked him what he was thinking about he replied, “I was wondering why I could not throw a small man like you, Sensei! Normally it is easy to throw someone small. But if I try to lift you, you feel heavy. I wonder why.”

“I said that it was not I who was heavy, but rather he who was weighed down. He didn’t understand what I meant. As I told you earlier, a stone weighing several thousand pounds is extremely heavy. But although the stone is heavy from below, it is easy to manipulate the stone from above. I was firmly grounded, attached to the earth. You can push me down from my head, but otherwise it is impossible to throw me. He did not understand that. I thought then that great people may know about the mechanics they learn at school, but they don’t know much about the reality of the mechanics of the universe.”

Noriaki Inoue talks about being ‘firmly grounded’ and about the ‘mechanics of the universe’, but these are terms of some complexity, with a distinct figurative or metaphorical use. From reading the interview, we are no further forward in understanding more precisely how Inoue was ‘firmly grounded’ (other than that his training partner could not move him) and how his understanding of the ‘mechanics of the universe’ was superior to that of his partner.

Rather than mention teaching strategies to enable the deshi to transmit understanding of the techniques, Shigemi Yonekawa, Rinjiro Shirata and other deshi all stress that the main differences between the uchideshi and ‘outsiders’ lay in the intensity of the training.

Here is Shigemi Yonekawa’s opinion (p. 124):

“There was no distinction whatever made between the uchideshi and the people who came from outside. However, as uchi-deshi, in contrast to the outside people, we would practice the techniques we were taught over and over again. We would practice the techniques repeatedly and take falls for Sensei. That was the difference. In addition, we trained together with many people from the outside under Sensei’s instruction. It would be incorrect to say that we assisted in teaching them. We trained together with them. That was one of the reasons the uchideshi progressed rapidly.”

Rinjiro Shirata agrees that there was no special training for uchideshi (p.155):

“There wasn’t any special training for the uchideshi. If there was, it was during the Budo Senyokai period in Takeda. In that dojo there were only people who trained hard like the uchideshi did. There weren’t any special classes exclusively for the uchideshi. The way of learning in those days was a little different from the present method. I think you could say that the old-timers learned each technique seriously one by one. Although people today learn techniques eagerly and seriously, in our time Ueshiba Sensei didn’t teach systematically. While we learned we had to systematize each technique in our minds and this was quite difficult. We never practiced techniques in any systematic order. It was not the sort of practice in which we were specifically taught techniques.”

Gozo Shioda even suggests that such training would be unacceptable nowadays (p. 175):

“In the old days it seemed as if he [Morihei Ueshiba] was acting as a medium for the kami rather than teaching. When we were training Ueshiba Sensei would make us feel things directly rather than teach us. He did not give detailed explanations telling us, for example, “turn forty-five degrees”, as we do today. That’s why at the time we had to study things on our own. He would say, “That’s right, that’s right”, or “Learn it on your own.” It was the old-fashioned apprentice system.”

“I suppose people nowadays wouldn’t be satisfied with this, but we were not taught systematically. Sensei acted according to his feelings and the conditions of the moment, so there was no connection between yesterday and today. That was the old method of teaching. We would absorb what we were taught and systematize it. We had to think about things by ourselves. I too have built on the foundation I acquired over a long period under Ueshiba Sensei. And now, I continue to do what I have been able to put together. People today can’t follow Ueshiba Sensei’s way of teaching. I think it’s difficult.”

Yoshio Sugino stresses the importance of ‘stealing’ techniques (p. 206):

“Ueshiba Sensei, in contrast to present instructors at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, taught techniques by quickly showing the movement just one time. He didn’t provide detailed explanations. Even when we asked him to show us the technique again, he would say, ‘No. Next technique!’ Although he showed us three or four different techniques, we wanted to see the same technique many times. We ended up trying to ‘steal’ his techniques.”

Mr Sugino then notes that Minoru Mochizuki was very good at imitating what Morihei Ueshiba showed. Like Morihei Ueshiba himself, Mochizuki was able to reproduce techniques after seeing them only once and this is understood by Mr Sugino to be the archetype of the learning process. Thus Mr Sugino notes that:

“…In other words, imitating is the same as stealing. You watch the techniques of your sensei with your spirit and your mind. This is what I mean by ‘stealing’ techniques from your sensei. People today are very slow to learn even when teachers explain. They are too casual about this sort of thing. People in the old days were very serious.”

Zenzaburo Akazawa briefly mentions the matter of self-training (p. 261):

“He (Morihei Ueshiba) would say, ‘Okay,’ and show a technique. That’s all. He never taught in detail by saying, ‘Put strength here,’ or ‘Now push on this point’ He never used this way of teaching.”

“O Sensei never taught exactly how to become strong or things such as that. This was not because he was worried that the students were trying to become stronger than him. There is no simple way round it. If you want to be strong you have to single-mindedly push yourself into that state known as muga no kyouchi, that is, the realm of no-self.”

Again, it would have been useful to us training nowadays to have had more explanation about precisely what being strong meant here. It seems to me that there are parallels with the later personal training that later deshi like Koichi Tohei and Hiroshi Tada undertook with the Tempukai.

Finally, Shigemi Yonekawa attempts to explain why an uchideshi’s relationship with the teacher cannot be systematized (p. 126):

“It’s very shallow to think that when you become an uchideshi you make rapid progress technically since you can practice many hours a day…I think there is a path or michi in these forms (i.e., the gestures of flower arrangement or tea ceremony) and that it is manifested in the tea ceremony or flower arrangement. It’s an extremely difficult thing. I believe it’s a matter of understanding for yourself those things that the teacher doesn’t teach, rather than a matter of learning to do a specific thing from your teacher.”

One strong impression gained from studying these interviews is powerful sense of nostalgia. Many of these uchi-deshi are thinking back to what they believe was a Golden Age, when famous martial artists were all heroes and the deshi were all together with Morihei Ueshiba in the Kobukan. They are sharply aware of the differences between this Golden Age and the ‘present’ state of aikido, such as they understand this. One possible consequence of this sense of difference is that some of these prewar deshi stopped training completely at the end of World War II. An intensely personal bond, forged for some uchi-deshi in a relatively short time, but with one man, was broken—and the break was considered irreplaceable.

Why are no learning strategies explained in the Aikido Masters interviews? I think this has to do with the cultural tendency (for want of a better term) to focus the learning process on the person who embodies the desired skills, rather than on the skills themselves. Having lived in Japan for so long, the reason seems clearer to me than it might be to aikido students in other countries. I think this cultural tendency offers a similar reason why the sempai/kohai system still flourishes in modern Japan. This system is a very traditional teaching/learning paradigm and one that also fits closely with the more distant role of shihan as model. In some respects this traditional vertically structured paradigm has not changed very much since Morihei Ueshiba lived and taught.

April is the real start of the new year in Japan and I am now facing classes of fresh-faced first year students as they attempt to make sense of what ‘Goldsbury Sensei’ (or the various nicknames I have) is doing in his philosophy and language classes, which are actually quite different from anything they have experienced before. They have been taught well by their high school teachers and sempai, so they have succeeded in entering a front-rank university like Hiroshima University. In facing the new challenges presented by Dr Goldsbury’s classes, they will usually resort to the same methods and ask their sempai, especially the sempai who took my classes earlier. They will rarely approach Goldsbury himself. These sempai, however, will not attempt to explain how to learn what I am teaching. They will not take one step back and try to explain the principles lying behind the class activities. No. If they have kept the material from my previous classes they will give the answers. Since I rarely repeat the same material, these explanations will be pretty fruitless.

I encountered a related problem a few years ago. I pulled up one student about his English and he replied that he had been taught the (incorrect) forms by his sempai, who had actually taught him far more skills than the professors whose classes he had attended. He was clearly torn between having to accept the mistake, because I was a native speaker, and being loyal to his sempai. A more Socratic learning paradigm, based on the importance of questioning, has no place for sempai and focuses more exclusively on the skills themselves, rather than on the person who embodies these skills. Again, I will come back to this point in future columns.

c. Morihei Ueshiba appears to have made no attempt to check whether they had understood what they had learned from him.

Since this column is already rather long, I will postpone further discussion of this point. However, I think the truth of this proposition is a consequence of the Teacher as Model and the Learner as Mirror paradigm. Apart from general observations during training, the only way Morihei Ueshiba appears to have checked the understanding of his deshi was by choosing or not choosing deshi as uke / otomo (bag-carrier & general assistant) when he taught classes or went on trips. I do not believe that he ever considered the need for actually checking their understanding and the reason is clear. This was not a matter worthy of his concern: whether they had understood, or not, would be obvious from their training and from the way in which they took ukemi.

Add comment