“Morihei was unique: a martial arts genius, and therefore in the nature

of things, this unique quality cannot be quantified or reproduced.”

The previous column ended with a brief discussion of the third proposition relating to transmission:

(c) Morihei Ueshiba appears to have made no attempt to check whether they had understood what they had learned from him.

As I stated earlier, I think the truth of this proposition is a consequence of the Teacher as Living Model and the Learner as Mirror paradigm. In Aikido Masters many of the uchi-deshi at the Kobukan stated that Morihei Ueshiba rarely showed the same waza twice and would not stop to give any technical explanations. The explanations given at the beginning of Budo Renshu are exclusively concerned with how to attack and how to move when so attacked. Of course, there are brief explanations of the drawings in the book, but these are of little value to those who do not already know how to practice the waza and Zenzaburo Akazawa suggested this in Aikido Masters.

(Akazawa actually stated that, “The only trouble is that things rarely work out as neatly as in those drawings because your partner is a living person. There’s always the danger of people coming to rely too much on this one book. Even though, those illustrations [NB. Not the explanations, which Akazawa never mentions] may well serve as guidelines or as a kind of yardstick. The sort of thing that helps you realize, ‘Oh, sure, in that situation that would be a possibility.’” Aikido Masters, p.263.).

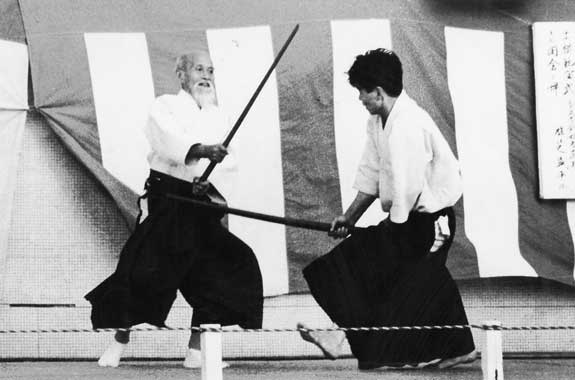

There is a passage in Aikido Shugyou, where Gozo Shioda discusses his grading test for 9th dan. Shioda visited Morihei Ueshiba in Iwama after the war ended. He gives the date as Showa 26, which would be 1951. The test involved attacking O Sensei, successively with a bokken and without any weapon, in any way possible. Shioda could not attack Ueshiba with the bokken because he could not find any openings in his stance. He noted that it was as if his hands and feet had been bound together. He almost landed an empty-handed attack, but O Sensei appears to have stopped him dead. Shioda was given his 9th dan and told to do more sword training. So it was indeed a test, and limited acknowledgement, of what Shioda himself had learned from Ueshiba, but it was all about suki, or openings, and did not involve any waza at all. (The discussion appears on pp.207-210 of 合気道修行.)

I think we need to unpack the above proposition a little further, because to understand it requires a distinct shift in our attitudes to teaching & learning. My third proposition was a direct follow-on from the second, discussed fully in the previous column:

(b) The latter all gained profound knowledge and skills during their time as deshi, but it is by no means clear that they gained all the knowledge or that all gained the same knowledge.

The important point here is: gaining all the knowledge or all gaining the same knowledge. Of course, there were the waza to be practiced every day, a sample of which is given in Budo Renshu and recorded in the Noma Dojo photograph archive. However, it is by no means clear that the Founder showed all of the uchi-deshi—or showed them all of—his own personal training exercises and rituals that he had learned from Sokaku Takeda and from Onisaburo Deguchi. I understand the third proposition in the same sense:

(c1) Morihei Ueshiba appears to have made no attempt to check individually whether each uchi-deshi had understood what each uchi-deshi had learned from him.

And not as (which is even less likely):

(c2) Morihei Ueshiba appears to have made no attempt to check whether as a group they had understood what they had (collectively) learned from him.

There is an important difference of emphasis here. Clearly, in Gozo Shioda’s 9th dan test Morihei Ueshiba had an opportunity to see whether Shioda could find any openings or gaps in his defence and was satisfied. But there is no record of him giving such a test to anyone else—not to Morihiro Saito, for example, who was his principal deshi at this time—and no indication that for Ueshiba it was a grading test as we understand the term. Later in his life O Sensei did not even bother with a test and was notoriously liberal in his verbal awards of 10th dan.

I think that to understand the proposition in the sense of (c2) is to jump too far into the future. I suggested that one cannot really think of the training in the early Kobukan as a seamless garment, even less as a seamless garment that can be put on and worn by different people. The collective checking of what deshi had learned, by means of testing, had to wait until the Master-Student paradigm had changed and I think this did not really happen until the Tokyo Hombu reopened and began to flourish under the direction of Kisshomaru Ueshiba.

Apart from occasional comments during training, the only way Morihei Ueshiba appears to have checked the understanding of his uchi-deshi was by showing them the waza and making sporadic corrections during training, by seeing how they looked after him outside training, and, most importantly, choosing or not choosing particular deshi as uke / otomo (bag-carrier & general assistant) when he taught classes or went on trips. I think the question of being uke, and the knowledge gained from being uke, is of some importance here and will return to this point below.

I believe that much stems from the fact that they had been chosen as uchi-deshi. I do not believe that he ever considered the need for actually checking their understanding and the reason is clear from the traditional Master-Deshi paradigm. I do not think it ever crossed Morihei Ueshiba’s mind to actually verify for himself whether or not they had understood what he had been showing them. This was simply not a matter worthy of his concern: whether they had understood, or not, would be obvious from their training.

The qualification, ‘or not’, is also important here, since the possibility has to be considered seriously that none of his uchi-deshi fully understood what Morihei Ueshiba was spending his entire life developing—and a major part of his life showing them. There are several reasons for this. One is that he was unique: a martial arts genius and therefore in the nature of things this unique quality cannot be quantified or reproduced. Another reason is that he showed them only waza—the tip of the iceberg—and left them to penetrate for themselves the vast legacy of personal training lying beneath the surface. A third reason is that they never cracked the code to begin with: they never succeeded in understanding the explanations he gave because they did not have time or skill for such private training. A fourth reason is that he really did not care whether they understood or not, even though he could see it from their training: it was simply not his responsibility as a Living Mirror also to make sure that the reflections in the mirror were adequate. This was the responsibility of his students, who at least had been afforded the opportunity to look closely in the mirror.

I would like to spend a little more time on the subject of the Master-as-Mirror, by considering two examples from my own experience. The first example is my teacher of Japanese; the second example is my teacher of aikido.

When I came to Hiroshima in 1980, I knew no Japanese at all apart from the few words and phrases I had learned as a result of aikido practice. My colleagues in the university were in two minds about my learning Japanese. On the one hand, a foreign teacher not knowing any Japanese at all would present a ‘fresh face’ to Japanese students and motivate them to work hard at making themselves understood, especially at examination time. (The foundation for this is a theory of language acquisition based on something like KI: you pour forth your ‘pure’ language KI and this motivates the students to extend their own KI and achieve linguistic matching, if not total harmony. This theory is quite pervasive and underpins the JET scheme in Japan.) On the other hand, in a local city like Hiroshima, total ignorance of Japanese would be a considerable handicap and no amount of English KI-pouring would achieve any matching or harmony in the supermarket.

So the professor who was responsible for appointing me suggested I learn some Japanese and offered to teach me Chinese kanji. However, he never actually gave me any formal lessons or set out to ‘teach’ me anything. What he actually intended was that I would read aloud the books he himself had written and then translate them. So, I would go to his house, read aloud a few pages of text in Japanese (which I had prepared beforehand) and give a verbal, and then a ‘real’, translation. After this we would have dinner. I still have these meetings nearly thirty years later and I think this is a fair example of an academic master-deshi relationship as this is traditionally conceived. (A similar relationship is sketched by Natsume Soseki in Kokoro.) I was allowed to have a privileged access to the mind of a literary craftsman as this issued in works of literature and criticism. The task of translating was merely the vehicle, the kata, for many conversations about literature and the art of writing. While no formal teaching took place, there was certainly learning—much learning—going on.

My aikido teacher is somewhat different. At the age of 70 he still actively teaches aikido and has recently received his 8th dan. However, he has never had any deshi and does not regard any of his students as deshi. There is no heir apparent and when he finally gives up teaching aikido, there will be no one to step into his shoes. He has produced no videos or texts and his extensive knowledge of the art will die with him. I have had as long a relationship with this teacher as I have had with my kanji professor, but he, too, does not think of formally ‘teaching’ anything. He trains in a very small dojo that is quite hard to find and does not actively seek new students. In fact there is a regular turnover of students and there is currently no one in the dojo who was there when I myself started in 1980. Students who have been there as long as I have can be counted on one hand.

I think the possibility that an art will die out because its creator is mortal is hard for people to accept, especially those who embrace the art as a ‘subject’, worthy of serious personal study, and not as the expression of a particular individual who was a Model. I have in mind those who believe that Morihei Ueshiba bequeathed the ‘art of aikido’ to the world as a ‘gift’ and that therefore it belongs to everybody those who practises it. This belief is unusually connected with the supposed spiritual and ethical properties of aikido, as a cure for the world’s ills.

I once asked Tada Hiroshi Shihan about the time when he would no longer be around to teach aikido, what arrangements he had made to transmit aikido to his own deshi. I think that the readers of AikiWeb can readily understand the logic behind the question. The spread of aikido overseas after World War II has largely been due to the efforts of Japanese shihan like Nobuyoshi Tamura, Yoshimitsu Yamada, Mitsugi Saotome, and especially Koichi Tohei, who are all known as supremely accomplished technicians of waza, if not as somewhat idiosyncratic individuals. So the question was really a repetition of the questions underlying these columns. What had these shihans done to distil their knowledge, so that it could be transmitted intact to their students?

Tada Sensei’s answer was striking, but not surprising. He had done virtually nothing beyond being as accomplished a model as possible. He had done his best to emulate his teacher(s) and show his students his personal training. It was up to these students to do the same. His own aikido would, of course, die when he did.

Add comment