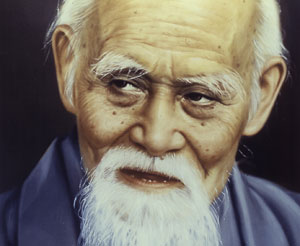

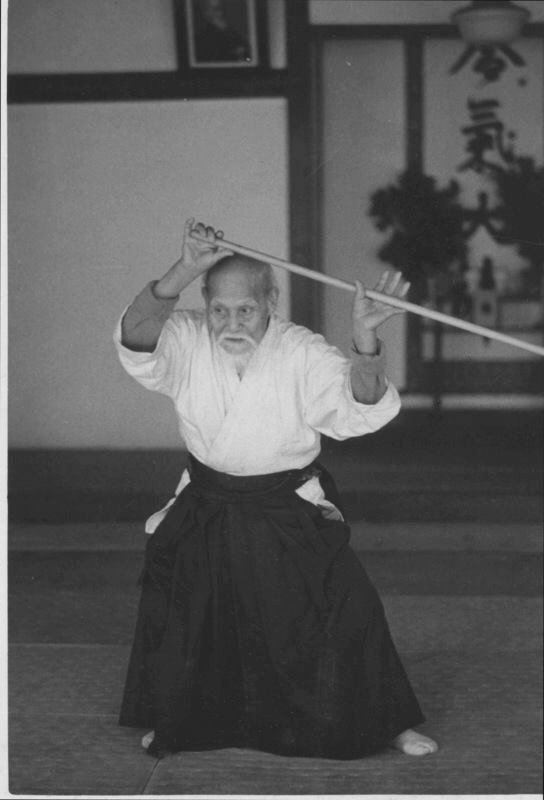

Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969) is known to most practitioners of Aikido as the art’s Founder. Who he was, and specifically what he did to create aikido, are little studied. Thus, aikidoka may have some vague notions of Morihei’s martial art and philosophy, but his life and vision do not play a major role in modern aikido.

In the postwar era, the Founder was often absent from the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Tokyo. His son, Kisshomaru and Koichi Tohei were the central figures in the operation of the headquarters dojo. Morihei was not in charge of instruction as he was in his prewar school, the Kobukan Dojo. He would make sporadic appearances at unpredictable intervals. What’s more, he would sometimes lecture at length about aikido in esoteric terms that were not easily understood by the younger generation of Japanese.

So, if we are serious about the study of aikido, and we want to have an understanding of Morihei’s original concept, we must do some digging. Otherwise, we are cut off from the source, and risk missing the depth, beauty, and potential of the art as conceived by its Founder.

Avenues of Study to Discover the True Principles of Aikido

As the title of my presentation today suggests, a study of Morihei’s involvement in war and religion during the prewar era will provide us with many insights about how his thinking evolved.

Before we delve into our discussion, I would like to point out the some of the difficulties involved in researching these twin subjects as they relate to Morihei Ueshiba.

First, as a defeated nation, many Japanese even today prefer not to talk about World War II and the country’s militaristic past. This reluctance naturally applies to the Ueshiba family and the administration of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

This presents an interesting dilemma. Morihei Ueshiba was very much a participant in Japan’s war efforts. He had extensive contacts among high-ranking officers in both the army and navy. Morihei taught for over a decade at Japan’s top military institutions as a combat instructor and strategist. He was tasked with preparing young men for battlefield encounters. He knew that many of his students would give their lives and suffer grave injury in warfare.

At the same time, the fact that a martial arts instructor had sufficient skills, charisma, and connections to walk among prewar Japan’s social elite is certainly a tribute to his exceptional character and discipline. For the founder of aikido, this is certainly a matter of great pride. And certainly, Morihei’s successors would mention these facts in speaking about the greatness of the creator of aikido.

So we have something like a case of cognitive dissonance insofar as concerns the Founder’s prewar activities. On the one hand, there is the desire to trumpet his many achievements. But on the other hand, there is guilt and embarrassment associated with his prominent role in the events leading to Japan’s defeat. It matters little that these are things that occurred 70 or 80 years ago.

The situation is similar in some ways with respect to Morihei’s religious activities, and even more complex. The Founder was a leading member of the Omoto religion, a so-called “New Religion” dating from the late 19th century. He was part of the inner circle of Onisaburo Deguchi, the charismatic sect leader and brain behind its spectacular growth.

The doctrine and religious texts of the Omoto played a great role in shaping Morihei’s spiritual beliefs. He regarded Onisaburo as his spiritual master and was extremely devoted to the causes that Deguchi espoused.

Here is where serious problems emerge. Not only was Onisaburo focused on expanding the activities of the sect and looking after its believers, he frequently provoked the Japanese government and engaged in politics and intrigue.

Onisaburo, too, was very well connected and conspired with a number of ultra-nationalist figures of the day to advance his religious agenda. This played into the hands of key right-wing leaders, especially those engaged in political and military activities in northern China.

These kinds of activities placed the Omoto on the government’s radar and led to its brutal suppression of two occasions, in 1921 and 1935. The latter event effectively crushed the religion and had a devastating effect on Morihei both professionally and privately.

So when we think of religion in Morihei’s life, we immediately think of the Omoto, yet this also leads us back to the arena of warfare and militarism through an alternate route. This is indeed a subject full of twists and turns that requires patient research to sort out.

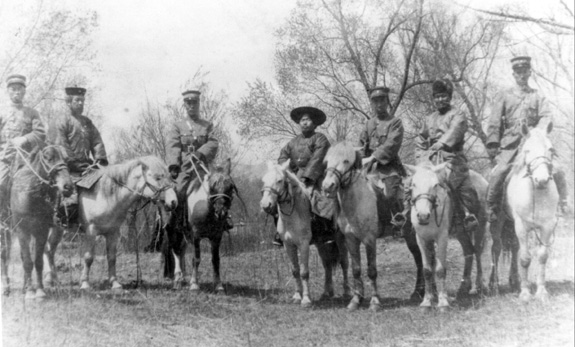

Soldier during the Russo-Japanese War

Let’s begin by documenting Morihei’s enlistment as a soldier while a young man, and the highlights of his involvement in military-related matters much later both in Japan and Manchuria. In the prelude to the Russo-Japanese War, Morihei joined the 61st Army Infantry Regiment of Wakayama in late December of 1903. He was 20 years old at the time. The build-up to the war was in response to Russian encroachments made in Northern China and Korea in the late 19th century. One of Russia’s aims was to secure for its use the warm-water port of Port Arthur for commercial and military purposes.

The Japanese reacted strongly to Russia’s military and trade activities in a region that it regarded as vital to its security and Asian empire-building intentions. The Japanese government made Russia’s maneuverings a national cause among the populace, and patriotic fervor gained hold of Japan. There was a strong push for a military armament and many young men joined the army and navy. Morihei was one of them.

Morihei had to overcome his short stature to be accepted into the army, and went to amusing lengths–for example, hanging upside down–to increase his height. Once admitted, he excelled during basic training, being possessed of exceptional strength, and proved himself to be adept at the use of the bayonet. Such skills meant the difference between life or death for the infantryman.

So we have something like a case of cognitive dissonance insofar as concerns the Founder’s prewar activities. On the one hand, there is the desire to trumpet his many achievements. But on the other hand, there is guilt and embarrassment associated with his prominent role in the events leading to Japan’s defeat. It matters little that these are things that occurred 70 or 80 years ago.

In one of his interviews, Morihei mentions being stationed in Dairen (present-day Dalian) in Northeastern China and having spent a year and a half at the front. It is uncertain the extent to which Morihei saw battlefield action. In his biography, Morihei’s son Kisshomaru, is somewhat vague about his father’s exact role. It does seem that he was at the front either as a foot-soldier or in a support capacity. Morihei recalled a number of wartime incidents where he miraculously survived by somehow being able to perceive the trajectory of bullets and cannonballs.

What is certain is that Morihei Ueshiba did spend a protracted period in the war zone and did witness the horrors of battle. There is no doubt that these experiences left a strong impression on the young soldier.

Expedition to Mongolia

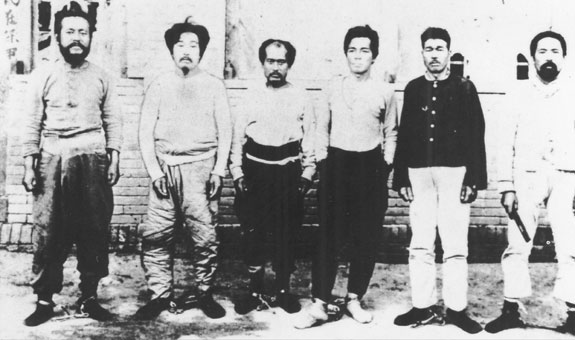

To document the next occasion in which Morihei found himself in a war setting, we must fast-forward 20 years. Interestingly enough, the scene was again northern China, Manchuria and Mongolia, to be specific. Morihei was a member of the party accompanying Onisaburo Deguchi, leader of the powerful Omoto sect, to Mongolia. Their party was on a secret mission to this region, ostensibly for the purpose of establishing a Utopian religious colony. Morihei’s served as a personal bodyguard to Onisaburo. We shall talk more about the relationship of the two shortly.

Onisaburo’s group was secretly supported by Japanese nationalist groups of the highest level in alliance with the Kwantung Army. This army was a quasi-independent part of the Japanese Imperial Army and little by little was bringing Manchuria under its control. Deguchi was deeply involved with the behind-the-scenes politics of the region, and he, the Japanese army and nationalists found each other useful in furthering their respective agendas.

During their journey in this disputed region, Onisaburo and company allied themselves with local militias and regional armies and participated in a variety of skirmishes. Without doubt, Morihei found himself in life or death situations on more than one occasion.

Onisaburo fell in with a rogue officer serving under a local warlord, and assembled what was basically a private army. With a force of about 1,000 men, this “religious army” marched into Mongolia as an “independence army,” with Onisaburo claiming to be an incarnation of the Dalai Lama!

In the end, things turned out badly for Onisaburo’s party and they were arrested and imprisoned by the local Chinese army. Morihei and his companions were resigned to being executed by the Chinese and even prepared death poems. Only the last-minute intervention by Japanese diplomatic authorities saved them from an untimely demise. There is a famous photo of the captured Japanese in foot shackles at the time of their imprisonment.

In one of his interviews, Morihei mentions being stationed in Dairen (present-day Dalian) in Northeastern China and having spent a year and a half at the front. It is uncertain the extent to which Morihei saw battlefield action. In his biography, Morihei’s son Kisshomaru, is somewhat vague about his father’s exact role. It does seem that he was at the front either as a foot-soldier or in a support capacity. Morihei recalled a number of wartime incidents where he miraculously survived by somehow being able to perceive the trajectory of bullets and cannonballs.

The party’s narrow escape with death had a profound effect on Morihei. On their return to Japan, he was plunged into a state of deep introspection and focused his attention squarely on his martial training and meditative exercises. The following year, 1925, would find Morihei in the initial stage of relocating to Tokyo where he would begin in earnest his career as a professional martial arts instructor.

This is the first of a three-part article. Read the second part here.

Two questions:

1. In your earlier essay this week, you thoroughly debunk the idea of O Sensei getting private instruction from a Chinese instructor on his own. Deguchi did have an open door policy to other religions and was not supportive of the Japanese government’s militarization. Did Deguchi have much in the way of contact with Chinese religious and martial arts figures, was Deguchi in the position to provide an introduction between O Sensei and a Chinese qigong practitioner or something like that? Were the only survivors of the “religious army” Japanese? (I consider it doubtful, but I am curious). I assume some of Deguchi’s activities in China might have been considered treasonous by the Japanese government?

2. Deguchi was arrested in 1935, O Sensei did not get arrested but did share his spiritual teacher’s view on the militarization of Japan. Did O Sensei have to publically separate himself or denounce his spiritual advisor? Was O Sensei’s retirement before or after the fire bombing of Tokyo? Did O Sensei leave in part because of Deguchi’s continued incarceration? When Deguchi was released from prison in 1945 a few years before his death, what was the relationship between these two like then? Did O Sensei continue to have a close relationship with Omoto Kyo after Deguchi’s death in 1948 until his own death in 1969?

Great series of articles this week, thank you.

Hello Stan,

My Mom knew my interest in history and subscribed to a history magazine and sent it to me. In the past year there have been a couple of articles about the Japanese Army against the Russians in the 1904 war.

I think your articles have stated that O’Sensei was attached to the 3rd Army. This army was tasked with taking Port Arthur. The Russians had made this port into a fortress with numerous outer forts on the hills around the city and covering the harbor. The general in charge sent his men in horrific suicidal frontal assaults to take these fortifications one by one. The casualties were like our civil war numbers. Tens of thousands of men died against much more advanced machine-guns and artillery.

Later in the year, another battle took place farther inland. The armies were strung out over a very long front, 30 plus miles wide. The 3rd Army was slow getting to the battle because they were still wrapping up Port Arthur. When they did get there they went into the center with more horrific losses. Because of the losses to both sides, that battle ended kind of in a draw with the Russians withdrawing and the Japanese too mangled to follow up effectively. There were also lots of casualties due to the cold weather in this second battle on both sides. Something like 15% of the casualties were due to cold weather.

A few months later in time the Japanese destroyed the Russian fleet in the straights between Korea and Japan by “capping the T”. The loss was so economically damaging to the Russians that their navy was unable to be of much effect for another 50 years or so. The long running dispute over the Kurile Islands was a result of this war.

I think if Morihei was attached to the 3rd Army during this time, he may have been in a rear support role, or taken out from sickness or he was super lucky to not become a casualty of those land battles.

I found the articles very interesting.

Good background information, Tom. Kisshomaru states that his father may have been in a support capacity when in the 3rd army. In any case, he was lucky to have survived those battles. There were a number of western journalists at the front reporting on the war. I published an excerpt with a first-hand account of the disposition of the Japanese army a few months ago.

Anyone, who has served in any war, as an infantryman, has seen his share of war.

Ask any infantryman today, who has served in any current war for 1 – 1/2 years, if he was not affected by war.

He was also a hand-to-hand instructor, as an infantryman, and had to demonstrate his skills on the battlefield.