This is the second of a three-part article. Read the first part here and the third part here.

Teaching as a military instructor in Tokyo

By 1927, Morihei had moved his family to Tokyo after spending seven years in the Omoto religious community in Ayabe, near Kyoto. This was done with Onisaburo’s blessing and support. For a period of four years, Morihei gave demonstrations and seminars, and taught in private venues. In 1931, Morihei finally succeeded in opening a fine private school in Tokyo called the Kobukan Dojo. This school is located on the same property as the current Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

Shortly into his stay in Tokyo, Morihei was hired as a military training instructor at a variety of army and navy institutions. These teaching opportunities emerged due to his wide range of associations with powerful persons in and out of government and his consummate skills as a martial artist.

Here is a list of his known assignments:

Naval Staff College (Kaigun Daigakko)

Army University (Rikugun Shikan Gakko)

Military Police School (Kempei Gakko)

Toyama School (Rikugun Toyama Gakko)

Nakano Spy School (Rikugun Nakano Gakko)

Naval Engineering School (Kaigun Kikan Gakko)

Yokosuka Naval Communications School (Kaigun Tsushin Gakko), Torpedo Technical School (Kaigun Suirai Gakko)

These teaching assignments at military institutions span the period of 1927 to 1942, after which Morihei retired to Iwama. The above list offers rather convincing evidence of Morihei’s extensive links to right-wing military figures and their activities.

Onisaburo’s group was secretly supported by Japanese nationalist groups of the highest level in alliance with the Kwantung Army. This army was a quasi-independent part of the Japanese Imperial Army and little by little was bringing Manchuria under its control. Deguchi was deeply involved with the behind-the-scenes politics of the region, and he, the Japanese army and nationalists found each other useful in furthering their respective agendas.

During this 15 year period, Morihei interacted with many high-ranking military officers and was surely abreast of the activities of various factions and their agendas. He also witnessed the intense military build-up of the nation, and Japan’s expansionary activities all over Asia.

Morihei would once again visit Manchuria on several occasions during the period of 1939-1942. His destination was the town of Shinkyo in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, now called Changchung in Chinese. This was the capital city of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, and coincidentally, the headquarters of the Kwantung Army. Morihei taught and gave demonstrations of his Aiki Budo at Kenkoku University, an institution mainly for Japanese and Chinese students.

Shinkyo was a hot-bed of military activity, and here the palace of Pu’yi, China’s “Last Emperor” was located. One of Morihei’s most senior instructors, Kenji Tomiki, had been living and teaching in Manchuria for several years. Tomiki was the regular instructor at Kenkoku University and was also involved in giving martial arts instruction to Japanese military police. Hideki Tojo, then Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army, briefly took lessons from Tomiki about 1937.

During these years, Morihei gave several widely praised exhibitions in Shinkyo as a distinguished member of the party of well-known Japanese martial artists who traveled to Manchuria to teach and demonstrate Japanese budo.

Devastation of Japan’s major cities and retirement to Iwama

Shortly after Morihei’s return from Manchuria in 1942, Japan was fighting on multiple fronts and the nation was on a war footing. The US forces had even managed to bomb Tokyo and other Japanese cities in April in the Doolittle Raid. Morihei, due to his army and naval connections, had access to information not available to the Japanese public. There is some evidence that Morihei did not fully approve of the decisions and conduct of the war of the militarist government.

Another telling fact is his resignation from all of his martial arts teaching posts at military and police institutions at the age of 58. The war was in full progress, and he had held these positions for some 15 years. If Morihei was in full support of the war and physically able, one would expect him to have continued to serve in this capacity as a patriotic Japanese.

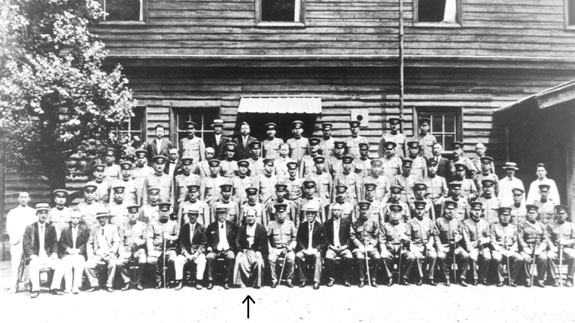

It seems that the main reason Morihei cited to leave his teaching positions was poor health. Indeed, it is documented that he had suffered a bout of jaundice in 1941. Also, at the time of his retirement to Iwama later in the year, it seems he was quite sick with an intestinal disorder. This is supported by a group photo from 1942 shortly before his retirement in which he appears emaciated and scarcely recognizable.

In any event, as the war worsened and Japanese cities and military targets were repeatedly bombed starting in 1944, Morihei was living in Iwama and suffered from further bouts of ill health. The war had a debilitating effect on him physically and mentally, and forced him to contemplate the true purpose of martial arts.

Morihei would once again visit Manchuria on several occasions during the period of 1939-1942. His destination was the town of Shinkyo in Japanese-controlled Manchuria, now called Changchung in Chinese. This was the capital city of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, and coincidentally, the headquarters of the Kwantung Army. Morihei taught and gave demonstrations of his Aiki Budo at Kenkoku University, an institution mainly for Japanese and Chinese students.

I will revisit this matter shortly.

Religion

Although an important part of the time frame of Morihei’s religious odyssey parallels his participation in militarism and war-related activity, I have chosen to treat them separately. In a Japanese context, we must understand religion as including worship, meditation, study of classical religious texts, rituals, and shamanistic practices, etc.

Morihei, like many boys of his age in the early Meiji period in the final part of the 19th century, received his basic education in a terakoya, a temple school, in his native Tanabe. Though physically weak, Morihei was an intelligent boy with a good memory and a penchant for mathematics. His early education took place at a school attached to a local Buddhist temple. Students were taught reading, writing, and basic mathematics. Since many of the textbooks used at these schools were written by priests, religious studies were also part of the curriculum. Morihei’s sister recalls that, at about age seven or eight, he studied the Chinese classics of Shingon Buddhism and displayed a keen interest in religious studies. It seems that Morihei’s mother wished for him to enter the priesthood. His father, however, was of a different mind and opposed the idea.

As he approached adulthood, his focus seemed to be more on developing himself physically and preparing for a career. In 1901, at at his father and wealthy brother-in-law’s urging, Morihei moved to Tokyo to prepare for a career as a merchant. He was 20 at the time. He began an apprenticeship in a stationery business of a wealthy relative. Morihei proved ill-suited for life as a merchant, and in his spare time, preferred to practice martial arts. Soon thereafter, he joined the army, as we have seen, where he served for about three years before being discharged in 1906.

Another telling fact is his resignation from all of his martial arts teaching posts at military and police institutions at the age of 58. The war was in full progress, and he had held these positions for some 15 years. If Morihei was in full support of the war and physically able, one would expect him to have continued to serve in this capacity as a patriotic Japanese.

Back in Tanabe in 1910, Morihei did involve himself in political activity that related to the Shinto religion. He supported famous naturalist Kumagusu Minakata in championing the cause of the anti-shrine consolidation movement. His group was resisting government seizure of Shinto shrine property and encroachments into traditional religion. Morihei was focused on the issues of social injustice and the attack against traditional religious practices for political and financial gain.

As he approached the age of 30, Morihei was still looking for a career direction. He finally immersed himself in a grand venture by relocating to the northernmost island of Hokkaido in the company of many members of his immediate family and some 54 families from Tanabe.

Of course, it was in Hokkaido that Morihei met the famous Sokaku Takeda in 1915, and began serious martial arts training. This was a decisive period in his life, and it was in the latter part of his stay in Hokkaido, that he began to think seriously about launching a career as a professional martial arts instructor.

Morihei’s stay in Hokkaido came to an end in late 1919 as he rushed back to Tanabe to be at the side of his dying father. On his journey back to his hometown, fate would have it that he took a detour to the town of Ayabe, in the mountains to the west of Kyoto. There he sought out the charismatic leader of the Omoto religious sect seeking to receive prayers for his father’s recovery. The leader of this New Shinto religion was Onisaburo Deguchi, the same man whom Morihei would later accompany on the expedition to Mongolia. This meeting with Onisaburo would determine Morihei’s life direction from that moment forward.

As he approached adulthood, his focus seemed to be more on developing himself physically and preparing for a career. In 1901, at at his father and wealthy brother-in-law’s urging, Morihei moved to Tokyo to prepare for a career as a merchant. He was 20 at the time. He began an apprenticeship in a stationery business of a wealthy relative. Morihei proved ill-suited for life as a merchant, and in his spare time, preferred to practice martial arts. Soon thereafter, he joined the army, as we have seen, where he served for about three years before being discharged in 1906.

After his delayed arrival in Tanabe, Morihei’s father had already passed away. Despondent and humiliated by his late arrival, Morihei entered a state of deep depression. His escape from this dark period was his decision to move with his family to Ayabe to be at the side of Onisaburo and his followers, and seek spiritual solace. This is where the religious phase of Morihei’s life really begins, and it is closely related to the later emergence of aikido.

This is the second of a three-part article. Read the first part here and the third part here.

Add comment