This is the first part of a two-part article. Read the second part here.

Introduction

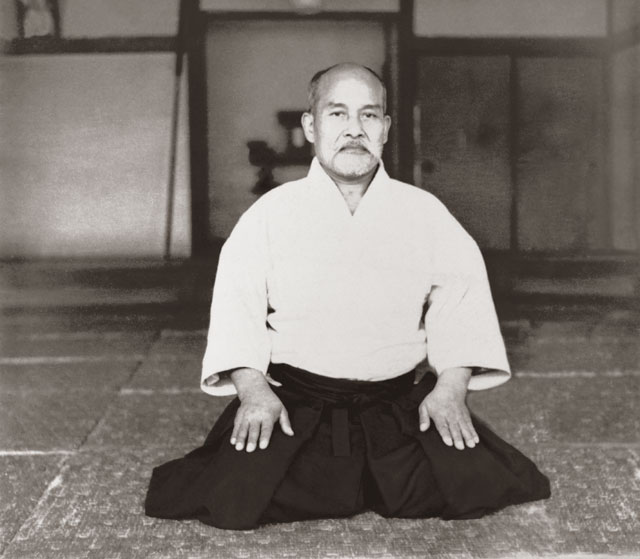

In April of 1931, Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido, opened a private dojo in the Shinjuku ward of Tokyo called the “Kobukan.” This dojo served as the center of the founder’s activities for more than a decade and is intimately related to the subsequent birth of aikido, Japan’s spiritual martial art.

During the Kobukan period, Morihei Ueshiba rubbed shoulders with the elite of Japanese society associating with luminaries from military, political, business and religious circles. Though not politically motivated himself, Morihei taught and interacted with many of the leading figures of the times, men who had deep respect for his incredible martial skills and who would shape Japan’s destiny as it hurtled toward war on the continent and in the Pacific.

In this short span of time, Morihei juggled a seemingly impossible teaching schedule that had him on the move all throughout the Tokyo and Kansai areas each month. His activities and achievements during this time span are so numerous and so fundamental to the emergence of modern aikido that that this topic deserves special scrutiny. To that end, we propose to divide our study into two parts.

The first section appearing in this issue of Aiki News will cover Morihei’s activities in Tokyo leading up to the opening of the Kobukan Dojo, the actual launch of the dojo, its most significant figures, the search for Morihei’s successor, the Budo Senyokai, expansion to the Kansai area, and finally the Second Omoto Incident and its aftermath.

Part two to be published in Aiki News 132 will discuss Morihei’s military and political associations, aiki budo in Manchuria, the establishment of the Zaidan Hojin Kobukai, the Dai Nippon Butokukai and the “naming” of aikido, the wartime uchideshi, and Morihei’s technical and grading systems.

Morihei’s activities from 1925-1931

The Kobukan Dojo was established after Ueshiba had spent about six years instructing in various temporary locations in the Tokyo area. His ties to Tokyo came about in large part due to the efforts of Admiral Isamu Takeshita, a long-time martial arts enthusiast. The relationship between Takeshita and Ueshiba began as a result of the introduction of another naval officer, Rear Admiral Seikyo Asano. Asano was a believer in the Omoto religion and began to practice Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu with Morihei in Ayabe in 1922. Thoroughly engrossed in the study of Morihei’s Daito-ryu, Asano recommended him to Takeshita, his classmate at the Naval Academy in Tokyo.

Takeshita journeyed to Ayabe in 1925 to view Ueshiba’s budo and left totally convinced that Ueshiba was an exceptional martial artist. Upon Takeshita’s return to Tokyo he presented a glowing recommendation of Ueshiba to retired Admiral Gombei Yamamoto—also a two-time former prime minister—and this led to a demonstration before a select audience at Takeshita’s residence. Henceforth, Admiral Takeshita played an active role in promoting Ueshiba’s activities among the elite of Tokyo society. Morihei made a number of trips to Tokyo from Ayabe to give seminars. This resulted in many military officers, government officials and wealthy persons becoming devotees of Ueshiba-style Jujutsu.

After Morihei’s move to Tokyo in 1927, he taught assisted by his nephew Yoichiro Inoue in a succession of temporary locations. Training took place first at Shiba in Shirogane, then Mita Tsuna-cho, followed by Shiba Kuruma-cho, and finally, in 1930, Mejiro. Morihei’s reputation had spread by word of mouth to the point that no more students could be accommodated in these small training facilities. Under these circumstances, a permanent solution was called for.

Soon donations were collected from Ueshiba’s circle of patrons to build a full-time dojo. Among the wealthy contributors to the dojo fund was a certain Koshiro Inoue who was related to Morihei by marriage. Koshiro’s brother Zenzo had married Morihei’s eldest sister Tame in the late 1800s in their native town of Tanabe in Wakayama Prefecture. The couple had eight children the fourth of whom was a boy named Yoichiro. Yoichiro’s uncle Koshiro built his fortune in Tokyo’s Asakusa district in the 1890s around the time of the Sino-Japanese War. Yoichiro—about whom we shall hear more later—was of course also Morihei’s nephew and his closest student at this time. Yoichiro would frequently tap Koshiro for funding for Morihei’s budo activities and Koshiro is said by surviving relatives to have made a large donation toward the building of the Kobukan Dojo.

After collecting sufficient donations and with the assistance of the wealthy Ogasawara family, Morihei succeeded in purchasing a plot of land in the Ushigome district of Shinjuku. The move to Mejiro was a temporary measure while construction of the new dojo was being completed. It was during the Mejiro period that judo founder Jigoro Kano made a special visit to observe a demonstration by Morihei. Highly impressed, Kano sent two of his top judo students—one of whom was Minoru Mochizuki—to engage in intensive training under Ueshiba. Another memorable event from the Mejiro period was the visit of General Makoto Miura who came to the Mejiro dojo to challenge Morihei. Miura had been a student of Sokaku Takeda some 20 years earlier and considered Morihei an upstart who had strayed from the Daito-ryu path. However, the General was powerless against Morihei’s technique and ended up becoming a long-time student and supporter.

Kobukan Dojo opening

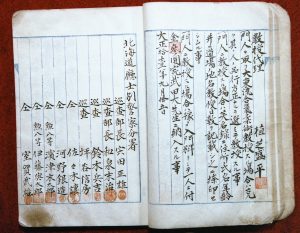

Before describing the grand opening of Morihei’s Tokyo dojo, mention must be made of a rather unusual event that took place just prior to the inaugural ceremony. Morihei’s Daito-ryu jujutsu instructor, the famous Sokaku Takeda, taught a seminar at the new dojo from March 20 to April 7, 1931. This is known because an entry bearing Morihei’s name and seal appears for these dates in Sokaku’s enrollment book (eimeiroku). Certainly, Sokaku had prior knowledge of the opening of Morihei’s private dojo because the two maintained a correspondence over the years. However, none of the circumstances of his visit to the Kobukan Dojo on this occasion are known. Sokaku visited Morihei periodically from the 1920s until the mid-1930s, sometimes without prior warning. The relationship between the two had become strained in recent years as Morihei had struck out on his own as a budo instructor. Morihei had been certified as a Daito-ryu aikijujutsu instructor in 1922, but the financial arrangement between the two remained somewhat vague and this proved to be a bone of contention. At this period of his career Morihei was well into the process of modifying the techniques of Daito-ryu into the more flowing, less jujutsu-like movements that would characterize his later aikido.

After Morihei’s move to Tokyo in 1927, he taught assisted by his nephew Yoichiro Inoue in a succession of temporary locations. Training took place first at Shiba in Shirogane, then Mita Tsuna-cho, followed by Shiba Kuruma-cho, and finally, in 1930, Mejiro. Morihei’s reputation had spread by word of mouth to the point that no more students could be accommodated in these small training facilities. Under these circumstances, a permanent solution was called for.

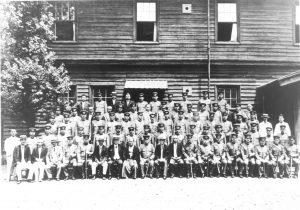

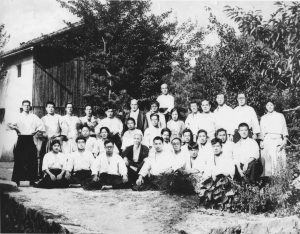

The official opening ceremony took place later in April 1931 after Sokaku had left Tokyo and was attended by many dignitaries including several high-ranking army and navy officers. There is a rare group photo that preserves a record of those present on that occasion. Among the VIPs in attendance were Admiral Isamu Takeshita, General Makoto Miura, Rear Admiral Seikyo Asano, Admiral Sankichi Takahashi, Dr. Kenzo Futaki, Harunosuke Enomoto, and retired Commander Kosaburo Gejo. Some of Morihei’s uchideshi and students who were present were Yoichiro Inoue, Hisao Kamada, Minoru Mochizuki, and Hajime Iwata. Morihei’s wife Hatsu and son Kisshomaru were also on hand. Fittingly, a horizontal calligraphy brushed by Onisaburo Deguchi—Morihei’s spiritual mentor— that reads “Ueshiba Juku” is on display in the dojo tokonoma. This same calligraphy was displayed on the wall of Morihei’s first school, the “Ueshiba Juku,” located in the Ueshiba home in Ayabe in the early 1920s.

The training area of the Kobukan Dojo consisted of 80 tatami and the structure also housed the Ueshiba family and uchideshi living quarters. Kisshomaru indicates that as many as 20 uchideshi could be accomondated in the dojo at a single time. The structure served for many years and survived the wartime fire bombing of Tokyo when most of the surrounding buildings were burned to the ground thanks to the timely efforts of Kisshomaru. It was used as the Aikikai Headquarters dojo until 1968 when the building was torn down to make way for the construction of the present Aikikai Hombu Dojo. The present Ueshiba family residence rests on the site formerly occupied by the Kobukan Dojo.

After his dojo was opened, Morihei received visits from leaders of the Omoto religion. Hidemaro Deguchi and his wife Naohi—Onisaburo’s son-in-law and daughter—paid several visits to the Kobukan around this time. A commemorative photo of one of these visits has survived and it is interesting to note that the calligraphy displayed in the tokonoma has changed since the opening ceremony. Several pieces of Hidemaro, a skilled calligrapher, were put up, no doubt in honor of the prominent Omoto visitors.

Training at the new dojo

The new dojo was used extensively and normally two morning and three evening classes were held at the dojo with uchideshi having an opportunity to practice at other times during the day. Trainees were relatively few in number and consisted usually of persons who had obtained introductions from at least two prominent people. Another source of students, especially among the uchideshi, were those with some connection with the Omoto religion.

Morihei’s teaching style was long on action and short on words. He would execute techniques in rapid succession with almost no explanation. His teaching method was not at all systematic. Yoshio Sugino, the famous Katori Shinto-ryu master, who studied at the Kobukan Dojo for about two years starting in 1931, describes what it was like when the founder was teaching class:

“Ueshiba Sensei, unlike present instructors at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, taught techniques by quickly showing the movement just one time. He didn’t provide detailed explanations. Even when we asked him to show us the technique again he would say, ‘No. Next technique!’ Although he showed us three or four different techniques, we wanted to see the same technique many times. We ended up trying to ‘steal’ his techniques.” [From an interview conducted by Aiki News in 1984]

Here is a recollection of one of Morihei’s first uchideshi, Hisao Kamada:

“Sensei would often use the term ‘irimi.’ This is a technique they did not have in judo. I guess it comes from Daito-ryu aikjujutsu, but I don’t know much about Daito-ryu. Ueshiba Sensei always said, “You have to enter to the inside of your training partner. Get to his inside and then take him into your inside!” He would start with ikkajo, nikajo, and suwariwaza. I don’t think he used the term “kukinage” (kukinage: lit., “air throw”; a popular judo technique of the period). There were techniques like yonkajo, but these were ways of training the body, while I believe that using them as applied techniques (oyowaza) is a matter of the spirit. The basics went about as far as gokajo, and after that it was applied techniques.“ [from an interview conducted by Aiki News in 1981]

The youthful uchideshi set the tone in training and practice was intense. There were very few females training at this time. One standout, however, was Takako Kunigoshi who was at that time a young art student. She is remembered most for her important work in sketching the hundreds of line drawings used in the Budo Renshu training manual published in 1933.

This stereotypically “old-fashioned” teaching approach is further described by Ms. Kunigoshi:

“No matter what we asked him I think we always got the same answer. Anyway, there wasn’t a soul there who could understand any of the things he said. I guess he was talking about spiritual subjects, but the meaning of his words was just beyond us. Later we would stand around and ask each other, ‘Just what was it Sensei was talking about anyway?’”

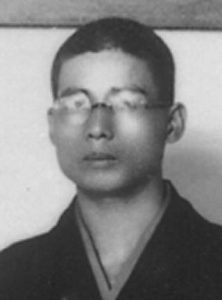

Ueshiba’s ubiquitous nephew Yoichiro Inoue

No discussion of this period of the Morihei’s activities would be complete without frequent mention of the role of his nephew Yoichiro Inoue. Inoue, who was Ueshiba’s junior by 19 years, spent part of his childhood in Tanabe and Hokkaido growing up in the Ueshiba household. He trained under Sokaku Takeda as well as his uncle and actually settled in Tokyo about 1925 prior to Ueshiba’s move from Ayabe. From a very young age, Yoichiro assisted his uncle as his partner in training and demonstrations. In the early days in Tokyo, especially, Yoichiro would teach as Ueshiba’s representative and substitute for the founder who was frequently ill.

Inoue appears often in the surviving group photos from the Kobukan Era and his importance to the development of aikido cannot be understated. Fate would have it that he had a falling out with his uncle shortly after the Second Omoto Incident that took place in December 1935. Although they sometimes would perform together in demonstrations thereafter, the two drifted apart and met only occasionally after World War II. Despite their one close relationship and blood ties, the rift between Morihei and Yoichiro never healed and they were not able to work together again. Books published on the history of aikido overlook Inoue’s contributions almost entirely and omit mention of the blood relationship that exists between the Ueshiba and Inoue families.

Search for a successor

From before the Kobukan period, one of Morihei’s preoccupations was the search for a suitable successor whom he hoped to marry to his only daughter Matsuko. Various anecdotes survive from several martial artist candidates with whom Morihei discussed the idea. These include Kenji Tomiki, Minoru Mochizuki, and Yoshio Sugino. It appears that at an earlier date the Ueshibas and Inoues had also entertained the idea that Yoichiro would marry Matsuko even though the two were first cousins. This actually was quite a common practice in the prewar era and it seems that even Morihei and his wife Hatsu, both of Tanabe, were distant cousins.

Finally in 1932, Kiyoshi Nakakura, one of Japan’s top kendoka and a student of Hakudo Nakayama, agreed to marry Morihei’s daughter. The arrangement was made with Morihei and Nakayama acting as go-betweens. The ceremony was held that year and Nakakura was adopted into the Ueshiba family and took the name of “Morihiro Ueshiba.” The founder not only had a successor, but a top swordsman who would stimulate his growing interest in the study of the sword.

Nakakura would remain at the Kobukan Dojo for approximately five years. Due to his presence, a kendo group was formed within the Kobukan and even entered competitions. As it turned out, Nakakura, first and foremost a kendoka, found it difficult to master the subtleties of Morihei’s jujutsu and gradually came to feel he would not make an appropriate successor. His marriage ended in 1937 at which time Nakakura returned to the kendo world.

After that, the issue of who would succeed Morihei again became an open matter. Many assumed that his nephew Yoichiro would become the successor given his long period of collaboration in spreading aiki budo and his kinship to Morihei. But as it turned out, Morihei’s son Kisshomaru started training in the mid-1930s and gradually began serving as his father’s partner especially for sword demonstrations. When Morihei retired to Iwama in 1942, Kisshomaru, by then a student at Waseda University, took over as the head (dojo-cho) of the Kobukan Dojo. When the founder passed away in 1969, Kisshomaru formally succeeded his father as the Second Doshu.

Outside teaching activities

The Kobukan provided a fixed base for Morihei’s prewar activities, but he was constantly on the move. Anyone studying the founder’s life during these years—and even in his final decade—is struck by the frequency of his travels around the Tokyo, Kansai, and Wakayama areas.

Inoue appears often in the surviving group photos from the Kobukan Era and his importance to the development of aikido cannot be understated. Fate would have it that he had a falling out with his uncle shortly after the Second Omoto Incident that took place in December 1935. Although they sometimes would perform together in demonstrations thereafter, the two drifted apart and met only occasionally after World War II. Despite their one close relationship and blood ties, the rift between Morihei and Yoichiro never healed and they were not able to work together again. Books published on the history of aikido overlook Inoue’s contributions almost entirely and omit mention of the blood relationship that exists between the Ueshiba and Inoue families.

Morihei’s duties in Tokyo alone kept him extremely busy. Besides the Kobukan Dojo, he taught classes and demonstrated at various businesses, clubs, and, on occasion, at private residences. However, his main outside activities involved teaching posts at several military institutions. These prestigious assignments came about through his broad network of contacts among high-ranking army and navy officers.

Although it is difficult to pin down the specific dates and circumstances of his military teaching career, we offer below a tentative listing of his assignments:

- Naval Staff College (Kaigun Daigakko), c. 1927-1937 through his contacts with Admirals Isamu Takeshita and Sankichi Takahashi.

- Army University (Rikugun Shikan Gakko)

- Military Police School (Kempei Gakko), dates unknown, through an introduction from General Makoto Miura.

- Toyama School (Rikugun Toyama Gakko), c. 1930-?, possibly through a connection with General Miura.

- Nakano Spy School (Rikugun Nakano Gakko), c. 1941-1942, through a connection with General Miura.

- In addition, brief teaching stints at the Naval Engineering School (Kaigun Kikan Gakko), the Yokosuka Naval Communications School (Kaigun Tsushin Gakko), and the Torpedo Technical School (Kaigun Suirai Gakko) of unknown dates are recorded.

The teaching assignments at military schools covered here span the period from about 1927 to 1942 when Morihei retired to Iwama. A glance at the above list offers rather convincing evidence of Morihei’s extensive links to right-wing military figures and their activities. We will delve into this subject further in part two.

It should be noted that with this heavy load of teaching responsibilities, the founder was forced to rely on a cadre of assistants to cover his commitments. Yoichiro Inoue was the senior of this group and shared instruction duties during the first years in Tokyo, but with the establishment of the Budo Senyokai the locus of Yoichiro’s activities shifted to the Kansai area. Morihei thus had to rely on his leading uchideshi—people such as Hisao Kamada, Kaoru Funahashi, Shigemi Yonekawa, Tsutomu Yukawa, and Rinjiro Shirata—for assistance.

Establishment of the Budo Senyokai

Although Morihei had physically distanced himself from the Omoto religion with his move to Tokyo in 1927, he still maintained close ties with members and leaders of the sect. In August of 1932, at the behest of Onisaburo Deguchi, an association for the promotion of martial arts called the Dai Nippon Budo Senyokai was created. Onisaburo had earlier set up numerous auxiliary organizations under the umbrella of the Omoto religion in an effort to accomplish specific tasks in the propagation of the sect. This association was tailor-made to support the efforts of Morihei in developing his budo and also served the purpose of demonstrating the patriotic role of the Omoto religion.

Morihei was appointed the first chairman of the Budo Senyokai. Branches were established all over Japan and training sessions were held at Omoto facilities even in far-flung places like the village of Iwama in Ibaragi Prefecture. Parenthetically, the existence of the Iwama chapter of the Budo Senyokai led to the enrollment in the Kobukan Dojo of Yonekawa and Akazawa, two of Morihei’s most valued uchideshi.

The official headquarters of the association were established in Kameoka, the administrative headquarters of the Omoto religion, but the large dojo opened in the town of Takeda in Hyogo Prefecture soon became the de facto training center. Several of the uchideshi of Morihei’s Kobukan Dojo in Tokyo were sent to Takeda at various times for intensive training and to assist in instructing. Yoichiro Inoue also played a significant role instructing at Budo Senyokai branches in the Kanto and Kansai areas.

Kisshomaru recalls that friction developed between Morihei’s students from Tokyo and certain hot-blooded Omoto believers—particularly members of the Showa Seinenkai (Showa Youth Association)—who practiced at the Takeda dojo. This amounted to something of a rivalry between the Kobukan Dojo and the Takeda school. [From Aikido Kaiso Ueshiba Morihei, pp. 223-223]

Yoichiro alluded to the type of young Omoto men who trained at the Takeda dojo of the Budo Senyokai by adding this perspective:

“We initially taught in Ten’onkyo in Kameoka. I was teaching then but as you know those practicing the martial arts are all the mischievous type! I couldn’t put them in place every time I went there. So I talked to Reverend Deguchi about the problem. He said: ‘Inoue, why don’t you get rid of them by sending them to Takeda?’ To tell the truth they were all kicked out of Kameoka! They say the reason was because a dojo was built in Takeda but that’s not true. They were sent to Takeda because they were so selfish.” [from Aikido Masters, edited by Stanley Pranin]

A total of 75 affiliated dojo were eventually set up giving a large boost to Morihei’s efforts to spread his aiki budo throughout Japan. It appears that there were even branches established on the continent and that Yoichiro and Aritoshi Murashige taught seminars in Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Korea in 1933 in connection with the Budo Senyokai. To a certain extent, other martial arts were practiced within the framework of the organization, in particular, kendo. In fact, Hakudo Nakayama was the kendo advisor to the Budo Senyokai and this undoubtedly was related to his friendship with Morihei. Nonetheless, the practice of Morihei’s aiki budo was the centerpiece of the activities of this organization.

Expanding to Osaka

One of the effects of the launching of the Budo Senyokai was the strengthening of Morihei’s network of dojo in the Kansai region. Coincidentally, at the urging of Mitsujiro Ishi in the spring of 1933, the Osaka office of the Asahi News contracted with Morihei to have him teach regularly at the newspaper dojo. Ishii had trained for a time under Morihei in Tokyo in the late 1920s during the Mita Tsuna-cho period and was a higher up at the Tokyo Asahi News office.

The timing of the commencement of training at the Osaka Asahi News office had to do with the occurrence of several violent attacks by political factions on the newspaper company because of its political stands. Ishii arranged for Morihei to give instruction at the newspaper in order to have the employees acquire self-defense skills to be used in an emergency.

The key figure at the Asahi News dojo was Takuma Hisa who had earlier worked in the Tokyo office performing well as a security director. In 1933, Hisa was promoted and transferred to Osaka and was thus a logical choice to oversee the Asahi News dojo given his work background and love of the martial arts.

Morihei began spending a week—some accounts say two weeks—out of each month in Osaka teaching at the Asahi dojo and other locations that had sprung up about this time. Several uchideshi from the Kobukan Dojo were soon assigned to Osaka. These included Tsutomu Yukawa who married and settled down in Osaka about 1934, Kaoru Funahashi, Shigemi Yonekawa, and Rinjiro Shirata. Since he was then based nearby in Kameoka, Yoichiro Inoue was probably the first of Morihei’s assistants to teach in Osaka.

Thus by the mid-1930s, Morihei was busy going back and forth between Tokyo and Osaka and, as we have seen, he had a large number of affiliated dojo throughout Japan due to the operation of the Budo Senyokai.

In June of 1936, a rather mystifying string of events led to Sokaku Takeda relieving Morihei of his teaching duties at the Asahi News dojo. Those interested in reading the details of this puzzling episode may refer to my article titled Remembering Takuma Hisa which appeared in Aiki News 129. Despite the fact he no longer taught at the Asahi News, Morihei continued his regular visits to Osaka and instructed at the other locations overseen by his uchideshi. For a time, Morihei even maintained a home in Osaka and he and his wife spent considerable time there.

Kisshomaru recalls that friction developed between Morihei’s students from Tokyo and certain hot-blooded Omoto believers—particularly members of the Showa Seinenkai (Showa Youth Association)—who practiced at the Takeda dojo. This amounted to something of a rivalry between the Kobukan Dojo and the Takeda school.

Second Omoto Incident

By 1935, Japanese government authorities had become increasingly irritated with the widespread activities of the Omoto religion that had arisen like a phoenix from the ashes of the brutal suppression of 1921 known as the First Omoto Incident. The sect now had something approaching two million adherents and was rapidly gaining in influence. In addition to the sect’s many domestic activities that irked the government, Onisaburo was heavily involved in the affairs of Manchuria and was advocating an independent nation under Pu’yi, the “Last Emperor” of movie fame. Furthermore, Onisaburo was suspected of funneling large amounts of money to various right-wing causes including the activities of Mitsuru Toyama and Ryohei Uchida. We will have more to say about these topics in part two.

The aggressive actions of the Showa Shinseikai, a new organization established by Onisaburo in July 1934, may have been the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back as far as the Japanese government was concerned. Luminaries such as Toyama, Uchida, leading politicians, army and navy officers, and many leaders from the business world and other fields attended the high-profile inaugural ceremony of the Shinseikai held in Tokyo. The organization espoused the broad goal of “universal love and brotherhood” (jinrui aizen) and promoted the “Sacred Imperial Way.”

Describing the purpose of the Shinseikai one year after its founding, Onisaburo wrote:

“The Showa Shinseikai means the changing of the order from ‘the spirit subordinated to the flesh’ to ‘the flesh subordinated to the spirit,’ thereby starting everything afresh putting it on a glorious path that accords with the principles of Heaven… The family spirit of true love will expand to the level of the state so that a brilliant Japan based on the spirit of one large family will be born, and this will further spread to cover the whole of humanity and the whole of earthly creation.” [From Deguchi Onisaburo Kyojin, by Kyotaro Deguchi]

By late 1935, the authorities hatched a secret plan to destroy the religion once and for all. A large-scale raid was launched on the Omoto centers in Ayabe and Kameoka before dawn on December 8, 1935. Onisaburo, his wife, Hidemaro Deguchi, Uchimaru Deguchi and scores of other Omoto leaders were arrested and imprisoned.

Morihei, too, was among those Omoto leaders whom the authorities had planned to arrest. At that time he happened to be in Osaka. He was forewarned of the crackdown on the sect by his student, Osaka Police Chief Kenji Tomita and was kept safely in hiding. Rinjiro Shirata, the former Kobukan uchideshi who was instructing in Osaka at that time describes this episode in a 1984 interview:

“The Kyoto Police Headquarters issued an order to the Osaka Police Headquarters for [Morihei’s] arrest because he was a leading member of the Omoto religion. It was sudden, but there was some advance warning. There was a man named Kenji Tomita who was Chief of the Osaka Police Department and an ardent admirer of O-Sensei. He believed that it was impossible for O-Sensei to be accused of lese majesty, and that although he was a member of the Omoto religion, he was devoting his life to budo. However, the Kyoto police said that if the Osaka police were not going to arrest Ueshiba Sensei they would send their own officers to Osaka to arrest him.”

Ueshiba Sensei was told about this immediately. There was a man named [Giichi] Morita who was head of the Sonezaki Police Station who was also a strong admirer of O-Sensei. He sheltered Ueshiba Sensei in his own house until the storm blew over. The police came from Kyoto to look for him, but since he was in the police chief’s house they couldn’t find him anywhere, not in Tokyo, Osaka, or Wakayama!

Back in Tokyo, the authorities also raided Morihei’s Kobukan Dojo in connection with the Omoto suppression. Kiyoshi Nakakura recounts what happened:

“[Ueshiba Sensei’s] wife, Hatsu, was also there [in Osaka]. I was in Tokyo. Kisshomaru was here also. In the Ueshiba Dojo there were shrines dedicated to Omoto deities and many framed calligraphic works by Reverend Onisaburo Deguchi hung on the wall. Mr. Ueshiba valued them highly. However, I tore all of them down and burned them. The uchideshi were surprised and asked me if it was all right for me to do so. However, it had nothing to do with being right or wrong. To hang up or display such things was an act of lese majesty. If Mr. Ueshiba’s wife had been present then, I don’t think I could have done such a thing. I could only do it because nobody was there.”

Aftermath of the Second Incident

The second attack on the church was designed to “leave no trace of Omoto” and had far-reaching consequences for Morihei both professionally and personally. The Budo Senyokai network of affiliated dojo was immediately disbanded, although apparently some groups continued training while maintaining a low profile. Morihei could no longer openly associate with Omoto believers or display images or symbols connected with the religion. The incident and its aftermath caused Morihei great stress as his life had been centered on the Omoto for some 15 years and he still held Onisaburo in the highest esteem.

Morihei was hurt deeply on a personal level as well. Many of the sect leaders thought it highly suspicious that Morihei escaped arrest given his prominent status within the religion and leadership of the Budo Senyokai. They regarded him as a “Judas,” a traitor to the Omoto cause. This reaction on the part of Omoto leaders was perhaps also related to the rivalry that existed within the Takeda dojo of the Budo Senyokai among the Kobukan Dojo uchideshi and the Omoto practitioners.

Even his own nephew Yoichiro seriously faulted Morihei for not sharing the fate of the brave Omoto leaders who were imprisoned and some of whom tortured. There arose a distance in their relationship, and even though they continued to associate on an occasional basis through 1942, this proved to be the wedge that eventually drove them apart.

To be continued… To read the second part of the article, click here.

Principal students of the Kobukan era

Noriaki Inoue, Wakayama Prefecture, 1902-1994

Noriaki Inoue is a nephew of Morihei Ueshiba and was raised for several years within the Ueshiba household, first in Tanabe and later in Shirataki, Hokkaido. Most of Inoue’s martial arts training experience was gained under the tutelage of Morihei Ueshiba while in Hokkaido, Ayabe, and Tokyo. Inoue was active in Tokyo as an assistant instructor under Ueshiba beginning in the mid-1920s, continuing through the establishment of the Kobukan Dojo. Later, from 1932 to 1935, he was a senior instructor for the Budo Senyokai, which was based in Kameoka. Inoue also taught aiki budo at various locations in Osaka.

Inoue distanced himself from Ueshiba Sensei following the events of the Second Omoto Incident and they met infrequently thereafter. He taught independently after the war in Tokyo, at first calling his art aiki budo. He later changed the name to Shinwa Taido, and then, finally, to Shinei Taido. He remained active teaching a small group of students until shortly before his passing in 1994.

Kenji Tomiki, Aikita Prefecture, 1900-1979

Hisao KamadaTomiki began training under Morihei in 1926 in Ayabe and continued in the late 1920s and early 1930s in Tokyo. After becoming a junior high school teacher, Tomiki would spend his summer and winter vacations in Tokyo to train with the founder. Since he was well-educated and a good calligrapher, Tomiki also helped with the various administrative chores at the Kobukan. For example, he edited the 1933 technical manual Budo Renshu.

Tomiki relocated to Shinkyo, Manchuria where he taught at the Daido Gakuin and Military Police Training Hall, and later Kenkoku University. He was awarded the first 8th dan by Morihei in 1940. Trapped in Manchuria at the end of World War II, Tomiki was imprisoned in the Soviet Union for three years before being repatriated in 1948.

In 1949, Tomiki joined the faculty of Waseda University where he taught judo and later aikido. He also taught at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in the early to mid-1950s. Tomiki later devised a system of competitive aikido known variously as “Aikido Kyogi” and “Tomiki aikido.” He continued to refine his system from his base at Waseda University until his death in 1979.

Hisao Kamada, Wakayama Prefecture, 1911-1986

Hisao Kamada was from a family of Omoto believers. He entered Morihei Ueshiba’s private dojo in Sengakuji, Takanawa in 1929. He was one of the senior uchideshi at the Kobukan Dojo where he also performed various clerical functions. In 1932, Kamada was dispatched as an instructor to the Budo Senyokai in Kameoka and Takeda.

Kamada entered the Imperial Japanese Army in 1933. After his discharge from the army in 1936, he relocated to Shanghai where he worked as an ice dealer and assisted Hajime Iwata who operated a dojo there. No longer active in aikido after the war, Kamada lived in Osaka where he worked as a leather goods dealer. In 1977 he retired to Ueda City in Nagano Prefecture where he passed away in 1986.

Hajime Iwata, b. Aichi Prefecture in 1909 [also Kazuya and Ikkusai]

Hajime Iwata entered Morihei Ueshiba’s private dojo in Mejiro in 1930 through an introduction from Dr. Kenzo Futaki. He was an uchideshi at the Kobukan Dojo while pursuing his studies in law at Waseda University. After graduation, Iwata was employed by the Tokyo Gas company until 1939 when he departed for Shanghai where he edited a publication entitled All Shanghai. In 1940 he opened a branch dojo of the Kobukai, where he was assisted by Hisao Kamada.

After the war, Iwata returned to Japan and later began teaching aikido in Aichi Prefecture. He is a ninth dan and was one of the few active instructors from the prewar era to teach after the war. Iwata is also a recipient of a medal from the Nihon Budo Kyogikai for his contribution to martial arts.

Minoru Mochizuki, b. Shizuoka Prefecture in 1907

Minoru Mochizuki began his martial arts training as a boy, practicing both judo and kendo. He progressed rapidly and in 1925 entered the Kodokan where he became a top-level judoka. Under the tutelage of Jigoro Kano, Mochizuki became a member of the Kobudo Kenkyukai, an organization established within the Kodokan for the study of classical martial arts where he practiced Katori Shinto-ryu. Later, in 1930, he was sent by Kano to study aikijujutsu under Morihei Ueshiba. Mochizuki became an uchideshi at the Kobukan Dojo for a short time and then opened his own dojo in Shizuoka City in November 1931.

Later, Mochizuki spent eight years in Mongolia where he received training in karate. In 1951, he traveled to France to teach judo and also aikido, and was the first to spread the latter art in Europe. Mochizuki is the originator of a composite martial system called Yoseikan Budo which includes elements of judo, aikido, karate, and kobudo. He authored a book entitled Nihonden Jujutsu in 1978. Mochizuki was awarded a tenth dan by the International Martial Arts Federation and until recently remained active at his private dojo in Shizuoka. He now resides in France with his son Hiroo.

Kaoru Funahashi, Tottori Prefecture (c. 1913-c. 1940)

Also from a family of Omoto believers, Kaoru Funahashi enrolled at the Kobukan Dojo in 1931. He was a relative of Morihei Ueshiba. Of short stature, he was one of the senior uchideshi at the dojo and was known for his skilled ukemi. He was one of the models who posed for the line drawings that appear in the 1933 Budo Renshu manual.

Funahashi was active as an assistant instructor at Budo Senyokai branches, including the large dojo in Takeda. He also taught in Osaka in the mid-1930s after which he ceases to be mentioned. Funahashi died from a lung illness around 1940.

Shigemi Yonekawa, b. Ibaragi Prefecture, 1910

Yonekawa entered the Kobukan as an uchideshi in 1932. He taught at various locations as an assistant to Morihei Ueshiba both in the Tokyo and Osaka area. In 1936, Yonekawa was Morihei Ueshiba’s partner for the series of technical photographs taken at Noma Dojo. This collection constitutes the most complete record of Morihei Ueshiba’s prewar techniques.

Yonekawa moved to Manchuria in 1936 where he assisted Kenji Tomiki in the instruction of aiki budo. He was drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army in 1944 and saw action in Okinawa before being repatriated in 1946. No longer active in aikido after the war, he settled in Tsuchiura, Ibaragi Prefecture where he is engaged in agriculture.

Tsutomu Yukawa, Wakayama Prefecture, 1911-1942

Tsutomu Yukawa entered the Kobukan Dojo in 1931 after graduating from middle school in Wakayama Prefecture. He had a background in judo and was known for his great physical strength. About 1934, Yukawa married a niece of Morihei and relocated to Osaka. There he taught aiki budo at the Sonezaki police department and later operated a private dojo in Osaka.

He appeared with the founder and Gozo Shioda in a demonstration before the Imperial family in 1941. Yukawa accompanied Morihei to Manchuria in 1942. Shortly after his return to Japan, he died tragically in Osaka as a result of an altercation with an army soldier.

Gozo Shioda, Tokyo, 1915-1994

The son of a noted pediatrician, Gozo Shioda enrolled in the Kobukan Dojo in May 1932, prior to entering Takushoku University. He became an uchideshi while still a university student and served as a teaching assistant to Morihei Ueshiba in the Tokyo and Osaka areas. Shioda trained under the founder until he left Japan in 1941. During the war, he worked in a civilian capacity in China, Taiwan, Borneo, and the Celebes.

After the war, Shioda spent a brief period training under Ueshiba in Iwama. Later, in 1952, he began teaching aikido to employees of the Nihon Kokan Steel Company and various police departments. In 1955, with the support of prominent businessmen, he established the Yoshinkan Aikido Dojo in Tsukudo Hachiman. Shioda launched the International Yoshinkai Aikido Federation to further the worldwide spread of the Yoshinkan style of aikido in 1990. He is the author of numerous technical books on aikido and an autobiography entitled Aikido Jinsei [An Aikido Life], published in 1985. Shioda held the rank of ninth dan and is the founder of Yoshinkan aikido.

Kiyoshi Nakakura, Kagoshima Prefecture, 1910-2000

Kiyoshi Nakakura started kendo as a boy and entered the Daidokan Dojo at the age of seventeen with the goal of becoming a kendo professional. Later, in January 1930, he moved to Tokyo to enroll in the Yushinkan Kendo Dojo of Hakudo Nakayama. Through his marriage to Morihei Ueshiba’s daughter Matsuko, he became the adopted son of the aikido founder and designated successor and was known as Morihiro Ueshiba during his five years at the Kobukan Dojo. He later abandoned his position and marriage, and left the Ueshiba Dojo to pursue his kendo career.

Nakakura had a long and highly successful career in competitive kendo and iaido which lasted into his seventies. Nakakura was a ninth dan hanshi in both kendo and iaido and one of Japan’s leading swordsmen. He was active as the head kendo instructor at Hitotsubashi University until his death.

Aritoshi Murashige, 1895-1964

Aritoshi Murashige was originally a judoka and practitioner of Katori Shinto-ryu at the Kodokan together with Minoru Mochizuki. He entered the Kobukan Dojo about 1932 having been sent from the Kodokan. Murashige’s main emphasis was on weapon training rather than jujutsu techniques.

Murashige later became an Omoto believer due to his association with Morihei Ueshiba and participated in Budo Senyokai activities. He engaged in intensive training at the Takeda dojo in Hyogo Prefecture and later served as an instructor for the Omoto organization. Later, Murashige taught Manchuria in this connection in 1933. After the war, Murashige taught in Burma in the 1950s and then in Belgium where he died in a car accident in 1964.

Rinjiro Shirata, Yamagata Prefecture, 1912-1993

Rinjiro Shirata entered the Kobukan Dojo in 1933 through a family connection to the Omoto religion. He became one of the leading uchideshi of Morihei Ueshiba, serving as a teaching assistant to the founder and instructing at outside dojo in the Tokyo and Osaka areas until conscripted into Japanese Imperial Army in 1937. Shirata was stationed in Manchuria and Burma during the Pacific War and, upon being repatriated, settled in his native Yamagata Prefecture.

After a training hiatus of more than 20 years, Shirata resumed teaching around 1960. He held several technical and administrative posts within the International Aikido Federation and traveled abroad to teach and attend organizational meetings on several occasions. In 1984, a training manual based on technique of Shirata was authored by John Stevens. Shirata was awarded a 9th dan and was active teaching in Yamagata until shortly before his death.

Takako Kunigoshi, b. Shikoku Prefecture, 1911

Takako Kunigoshi entered the Kobukan Dojo in 1933 just prior to her graduation from Japan Women’s Fine Arts University. One of the few female students at the Kobukan Dojo, she trained seriously and gained the full respect of both Morihei Ueshiba and his uchideshi. A skilled artist, Kunigoshi did the technical illustrations for the 1934 book Budo Renshu, which was given to students in lieu of a teaching license. She later trained at the private dojo of Admiral Isamu Takeshita for several years and taught self-defense courses to various women’s groups.

After the war, Kunigoshi was no longer active in aikido. She is now retired and resides in Ikebukuro where she gives instruction in the Japanese tea ceremony.

Zenzaburo Akazawa, b. 1919, Ibaragi Prefecture.

Zenzaburo Akazawa is from a family of Omoto believers and first came into contact with aiki budo because of the existence of a Budo Senyokai group in Iwama, Ibaragi Prefecture. Also a relative of Kobukan Dojo uchideshi Shigemi Yonekawa, Akazawa entered the Tokyo dojo in April 1933 after graduating from middle school. After a short period of training at the Kobukan, he spent two-and-a-half years of intensive training in Takeda, Hyogo Prefecture at the large Budo Senyokai dojo. Following this, he returned to Tokyo where he continued as an uchideshi until leaving for Manchuria at the age of 18. Morihei Ueshiba and Akazawa formally enrolled in the Kashima Shinto-ryu school in 1937 as the aikido founder became absorbed in the study of weapons, especially the ken and jo. Akazawa practiced Kashima Shinto-ryu for about a year at the Kobukan Dojo when instructors from the ryuha visited each week.

Later, Akazawa entered the Imperial Navy and was at sea for three years. During the latter part of his naval service he was assigned until the end of World War II to teach aikido at the Naval Academy in Etajima in Hiroshima Prefecture. Akazawa’s father assisted Morihei Ueshiba in purchasing land in Iwama and then was instrumental in the construction of the Iwama Dojo and the Aiki Shrine. No longer active in aikido, he resides in Iwama.

This is the first part of a two-part article. Read the second part here.

Great article. O’Sensei’s history is so rich and dynamic. We are blessed to have you research so deeply and share with us. Thank you. Even though his teaching style is always described as somewhat difficult, I always imagine that there had to be some type of charisma or something to his personality and way of teaching for him to have gathered the type of following he had. There were many skilled martial artists and even people who had a hard time “getting it”, still chose to follow. Very interesting!

Thank you Hector for your kind words. Yes, O-Sensei was full of charisma!

Great article, question…where i could get the full picture of the Kobukan oppening that is show here on the top of the article. Has great quality.