“Morihiro Saito told me on more than one occasion that

he skipped two ranks in his advancement to 9th dan.”

The other day I found an interesting article in the 33rd issue of the “Aikido Shimbun” published in March 1962. You may recall that the Aikikai Hombu Dojo began publishing this four-page newsletter in 1959. The newsletter has appeared continuously through today, an enviable publishing run of over 52 years!

What caught my eye was an announcement listing the dan promotions awarded on January 15 of the same year at the annual Kagami Biraki celebration. A number of famous names are mentioned in that list, some of them prewar students of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, while others began training following World War II.

I have selected certain names of people that have become prominent and added the year of their enrollment by way of reference.

8th dan

Rinjiro Shirata (1933)

Hajime Iwata (1930)

Takaaki (Shigemi) Yonekawa (1932)

7th dan

Morihiro Saito (1946: 16 years to 7th dan)

6th dan

Zenzaburo Akazawa (1933)

Shoji Nishio (1951: 11 years to 6th dan)

Nobuyoshi Tamura (1953: 9 years to 6th dan)

5th dan

Hiroshi Kato (1954: 8 years to 5th dan)

Hiroshi Isoyama (1949: 13 years to 5th dan)

4th dan

Yoshio Kuroiwa (c. 1954: 8 years to 4th dan)

3rd dan

Masatake Fujita (1956: 5 years to 3rd dan)

Koretoshi Maruyama (1957: 5 years to 3rd dan)

Katsuaki Asai (1955: 7 years to 3rd dan)

If you look at the number of years of training resulting in the indicated rank, you will find certain cases where the progress of dan promotions was very rapid. For example, three years to 3rd dan, or nine years to 6th dan–as in two of the cases cited–would be considered an aberration by today’s standards.

This sort of rapid advancement, or “dan inflation,” if you like, was a common occurrence in the 1950s and 60s. The reasons have to do with the fact that aikido was a new martial art, and relatively unknown to the general public. One of the most effective means of promoting aikido were public demonstrations. When aikido was being demonstrated by so-called “experts,” it would seem odd to have people of low rank representing the art. But since aikido was new, there were not yet very many highly-ranked practitioners.

Also, in the case of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, there existed a kind of a rivalry with the rapidly expanding Yoshinkan Aikido established by Gozo Shioda. In the early years following the war, the Yoshikan school was more active than the nearly dormant Aikikai which still had bombed-out families living in the Hombu Dojo. As the separation between the Aikikai and Yoshikan was not as distinct as today, representatives of both schools would sometimes appear in the same demonstration. The Yoshikan rapidly advanced their senior teachers and standout students, and the Aikikai followed suit so as not to be looked upon in a lesser light.

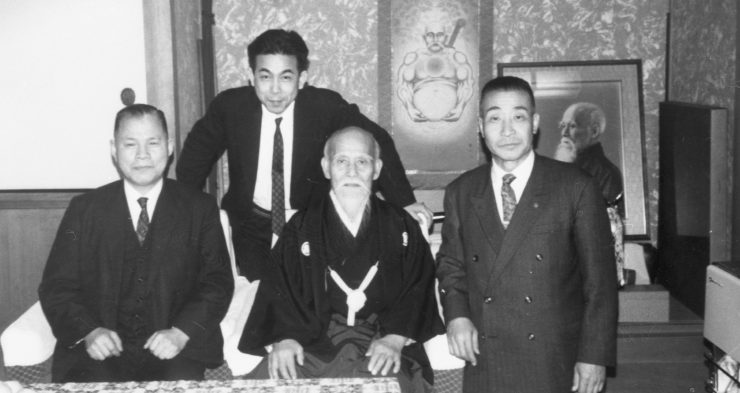

My own teacher, Morihiro Saito told me on more than one occasion that he skipped two ranks in his advancement to 9th dan. There were a number of other prominent teachers who experienced the same thing. The “Aikido Shimbun” is a good source document for tracing this early progression through the rankings of well-known instructors.

As aikido became established over the years, generally speaking, standards became more stringent, and today it is not uncommon for it to take three or more years to reach 1st dan, and several more years for each dan thereafter.

If you think about it, the early instructors who were sent abroad to disseminate aikido were, comparatively speaking, still novices in the art. Many of them, however, made rapid progress because of the difficult conditions and challenges they faced in setting up dojos and organizations overseas. They may have been promoted rapidly early on, but their reputations as aikido experts were built through long periods of hard work and strenuous testing of their mettle.

This article from “Aikido Shimbun” was enlightening in several ways. Thank you Mr. Pranin. I come to think of a friend of mine, she’s one of Sweden’s foremost aikidoka’s (graded to Godan), with a PhD in Japanology. She said to me that non-Japanese will never “be given the best seats in the room” (meaning ranking) since they do not have the “Japanese vertebrae”. I wonder if there will ever be a non-Japanese Hachidan?

Bertil,

Nice to connect with you here. I just reread this article and saw your comment from 2012. Indeed there would be a non-Japanese hachidan. There are now a number of them, which is fantastic for the aikido world.

I think that the promotions that have elevated non-Japanese practitioners to Hachidan indicate an evolution and balancing of standards in the Aikido World. On all levels the promotions are universally justified. On this continent, Frank Duran Shihan and in France Christian Tissier Shihan, are two outstanding examples. Both promotions broach no challenge. Both stand on a merit that exemplifies what the positives of what Aikido has become and what it has yet to become. I believe because of these and others… there is a level of trust evolving in the Aikido world regarding recorded ranks and representatives of O’Sensei’s legacy.

I agree 100%. I think it’s a very positive development in the aikido world and it’s great to see the progress.

George Eaton, head of the Australian branch of the Takemusu Aikido Kai, is a hachidan.

I love the new Aikido Journal, Mr. Gold. Thank you so much for all you have done, and please accept my deep condolences on the passing of Stanely Prannin Sensei.

Thank you for your kind words. It’s nice to connect with you here.

Thank you so much Brendon. It’s my honor to support the aikido community and I’m delighted you love the new Aikido Journal. It’s great to have you as part of the community.

Sincerely, after switching to Aikido from another martial art where I held third dan, I am rather lacking motivation to be tested at all. I previously taught at the school at another martial art, which I don’t do now. To me, it is sufficient to practice whenever I find a day. I believe testing and promotions rather interfere with my progress as martial artist.

Dan ranking is for marketing and relatability to a world of beings enmeshed and enamored with competitive striation, it is a path of expedient means to help society find peace and harmony. It is a reflection of attachment to self, we, and brand, shed. Do not climb the wrong mountain; and ask, does this practice lead to the cessation of aggressive behavior or lead to the proliferation of it?

As such through the practice of letting go of self-view, and arriving at the wisdom of emptiness, the true mountain of rank is climbed, and it is a steep mountain, and it is a just mountain, and it does not falter for it is connected to the earth rather than perception.

Do not confuse marketing with reality, though marketing may help preserve warmth and keep one well fed, even monks wear saffron robes and carry begging bowls. This is samsara after all.