The following translation from the Japanese-language autobiography entitled Aikido Jinsei (An Aikido Life) by Gozo Shioda Sensei of Yoshinkan Aikido is published with the kind permission of the author and the publisher, Takeuchi Shoten Shinsha. The series began with AIKI NEWS No. 72 Read the ninth part here.

Chapter 3: Days of Wandering

In April 1941, I finally graduated from Takushoku University. Due to my participation in the Kobe Incident as mentioned above, the Minister of War, Shunroku Hata probably thought it was not a good idea for me to stay in Tokyo. At that time, he held the important position of General Commander of the Expeditionary Force to China. Thus he issued an official announcement of my appointment as his private secretary at the same time I graduated from the university.

To China

Since it was my long-cherished dream to embark on a great venture abroad, I began preparations to leave for my new post considering it an opportunity to try my fortunes as a man. I went to China alone in early May 1941. As soon as I arrived in Nanking I went to the house of the General Commander. General Hata was very hospitable and ordered an army civilian employee uniform for me. At that time, army civilian employees were classified by a badge indicating their class. I had no insignia in particular and was a “lord steward” without a crown. In those days, my monthly salary was 100 yen. The value of money was much different from now and 100 yen would go a long way in those days. All of my meals were provided by the headquarters and I lived in an official residence. I hardly had to pay for anything. I used to treat the soldiers and drink with my comrades. I lived in easy circumstances. Though I was a private secretary, I had nothing to do. As Adjutant N. did most of the work I idled my time away all day long.

As the old saying goes, “The idle mind is the devil’s playground” and nothing good results if a young man fritters away his time without working. I thought about many things as I passed away the time, and decided to visit Lieutenant Colonel Sakurai in Yusuichin where Jiang Jie-shi and Sou Birei are supposed to have kept their love nest in the old days. Yusuichin is a hot-spring resort about 40 kilometers from Nanking and is akin to places like Hakone or Atami in Japan. At that time it was a health resort for the sick and wounded soldiers of the army. Colonel Sakurai was a stout-hearted and straightforward man. He was recovering his health after a harakiri attempt. I wanted to see him very much. I asked General Hata for permission, but he rejected me flatly. It seems that the road to Yusuichin was a lawless area infested with bandits and very dangerous. I went to General Hata again to renew appeal. Due to my youthful ardor I wanted to take the risk and see Colonel Sakurai. The General again flatly refused. I got angry and said, “Then there is nothing for me to do but to go by myself.” As I left the room, the General spoke in a resigned voice and gave some order to Adjutant N.

A while later, General Hata said, “Preparations have been made now.” I said with a bow, “Thank you very much,” and left. To my surprise, the license number of the car read “Soichi”—it belonged the General – and there was a truck to the front and rear of the car, each with 20 soldiers with machine guns and side cars also with machine guns on the ten and right. I felt deeply embarrassed. I got in the car of the Commander General and set out. All of the soldiers on the road saluted me. It must have been the car rather than me.

Treating the Soldiers to a Great Feast

Nothing happened and we arrived at our destination after about an hour. I talked with Colonel Sakurai about many things and started on my way home. I felt sorry for the more than 40 soldiers whom I took with me out of my selfishness. I decided to treat them all to a cup of laochu sake at a pleasure resort in a suburb of Nanking on the way back home. At that time a system was in effect where employees of the general headquarters had tickets issued by the General Accounting Section and we could eat or obtain anything we needed if we signed and handed them in. At first, I intended to treat them only to a cup of sake. However, I became emboldened and next treated them to a large amount of food and drink because I had many tickets. Everyone was very happy and said to me, “Mr, Shioda, let’s go often to Yusuichin!” We returned home in an exultant mood. The bill for this outing was 3,000 yen, Nowadays, 3,000 yen is not very much, but at that time it was a great deal of money. Initial salaries at private companies for university graduates in those days were as follows: 75 yen for national universities, 70 yen for private universities, and 55 yen for special college (present junior college) graduates. This amounted to my salary for about two-and-a-half years. If you compare the amount with these figures you get an idea of what a large sum of money it was.

In April 1941, I finally graduated from Takushoku University. Due to my participation in the Kobe Incident as mentioned above, the Minister of War, Shunroku Hata probably thought it was not a good idea for me to stay in Tokyo. At that time, he held the important position of General Commander of the Expeditionary Force to China. Thus he issued an official announcement of my appointment as his private secretary at the same time I graduated from the university.

When I left I was in a good mood, but when I returned things were different. As soon as I arrived back, General Hata thoroughly scolded me. I was placed on my good behavior and after a few days the General called me in and said, “Why don’t you go to Beijing and work as a school teacher for a while.” Since I was bored I instantly consented to the idea.

He said to me, “I am going to write a letter of introduction to a certain person. Go to him.” Then he wrote me a letter to Mr. C. The next day, I left for Beijing in a military plane to my destination, the Hanazono Manor. It was a school where the Japanese language was taught to young Chinese. There I met Mr. C to report my arrival. He seemed to be a well-mannered and honorable person. Later I learned he was idolized as a loving father by the Chinese people. He treated me courteously perhaps because I had a letter of introduction and told me in detail about the nature of my work. My position at the school was as the director in charge of staff administrative affairs. The work was not difficult. I kept the roll-book of the staff that came to school at nine a.m. each morning and made a speech when the school opened and closed each school day. I had no other work to do. Since I was given a car I gladly drove around—I was able to drive since I had taken lessons. It was not necessary to go to the trouble of getting a driver’s license in the battlefield.

Receiving Gasoline in the Name of the General Headquarters

However, even in Beijing, as in Japan gasoline was rationed among the general public. Mr. C told me to use the car only for coming and going to school from my billet in the suburbs of Beijing.

One day I said to Mr. C, “Can I use the car for other purposes if I can get gasoline from the outside?” He answered that if I could get more gasoline I was free to use the car in any way. Then I had an idea.

I still had my identification card as the private secretary of the Commander General of Expeditionary Force to China. First I went to the military police detached to Beijing and asked for an interview with its head, a captain, and showed him my identification card. He looked surprised and asked what my duties were in Beijing. I spoke ambiguously and said, “Combined with the observation of the school, and so on…” When I studied the captain’s face, he looked puzzled. Then he said, “If you need something, please tell me.” I was very glad, but I told him in an even tone of voice, “The fact is I have a car, but I don’t have enough gasoline since it is rationed.” He readily agreed and said, “Don’t worry. I will prepare gasoline for you. Please tell me your address.” I gave him my address and went back to my billet. To my surprise, after a couple of hours he brought fifty cans of gasoline in trucks despite the supposed shortage! Each can contained 18 liters. He said when I used it up to call him any time and left.

A while later, General Hata said, “Preparations have been made now.” I said with a bow, “Thank you very much,” and left. To my surprise, the license number of the car read “Soichi”—it belonged the General – and there was a truck to the front and rear of the car, each with 20 soldiers with machine guns and side cars also with machine guns on the ten and right. I felt deeply embarrassed. I got in the car of the Commander General and set out. All of the soldiers on the road saluted me. It must have been the car rather than me.

My billet was very nice and one man and one woman were working for me. They handled all miscellaneous matters and thus I was living in quite easy circumstances. My purse was well-lined since I was receiving a monthly salary of 250 yen – 150 yen as a teacher and 100 yen from the army general headquarters. The captain came to see me every three days and took me to many interesting places. I was able to see many wonderful sights with the captain of the military police as my guide. I was “a small man acting arrogantly on borrowed authority”.

I went to the school every day and was present for the staff roll call. Among the teachers there was a woman whose Japanese name was Sumiko Tanaka. She spoke fluent Japanese and was teaching Japanese conversation to the Chinese- She was a beauty. I was 26 years old and she was 18. I often took her out for drives or to eat and we were a well-matched couple. Sometimes when we were out driving we were stopped by soldiers with bayonets. In those cases, my identification card was very effective. When the soldiers with bayonets saluted me and said, “Thank you very much” while standing at attention I was embarrassed. Such incidents during those war-torn times reveal my impudence, but I enjoyed those dates.

Tourist in Shanghai While on Assignment

I learned a lot about real life in Nanking much as I had while living in Beijing. Then, finally, I was called back again because I learned too much after the captain made a detailed report to headquarters. Early in July of 1941 I was again summoned by General Hata. After he had suffered through several bitter experiences on my account, the General handed me three letters and said. “Now please go on an errand for me.” One letter was addressed to the army chief of staff in Taiwan. Lieutenant General Takaji Wachi, the second to the General Commander of the Expeditionary Force to Canton, Lieutenant General Ushiroku, and the last to the chief of staff of the Expeditionary Force to French Indochina, Isamu Cho. General Hata said, “I have already arranged for a plane to Hanoi so go there directly.” He gave me 3,000 yen as pocket money. I boarded the plane in high spirits. Thus, in the hot July summer of that year I took off from Nanking and landed in Shanghai for a short rest. I happened across a friend named Uraoka who was wandering around inside Shanghai airport. He has since died, but he was my junior at the private school I operated during my Takushoku University years. He was working in the secret service for the Iwai Diplomatic and Consular Office, an agency of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This organization was established to counter the secret organization known as the “Ranisha” of the Jiang Jieishi government. He was courageous by nature. As soon as he saw me, he rushed up like a hunting dog and said, “You’re Shioda, aren’t you? I’m so glad to see you!” We were delighted to happen across each other and embraced.

It is something wonderful to accidentally run into a friend in a foreign country. Absorbed in memories of the good old days, I forgot about the future completely and left the airport to be led to the New Asian Hotel, the best in Shanghai.

When I left I was in a good mood, but when I returned things were different. As soon as I arrived back, General Hata thoroughly scolded me. I was placed on my good behavior and after a few days the General called me in and said, “Why don’t you go to Beijing and work as a school teacher for a while.” Since I was bored I instantly consented to the idea.

Unlike Nanking, there were many high-rise buildings and many kinds of people bustling about in Shanghai. I felt as if I were in a totally different country. Parenthetically, the hotel charge was extremely high – 60 Yen for one night just for the room. Of course, to this was added the cost of meals—Furthermore, the large group of mischievous young men who came with us ate and drank a great deal and I soon ran short of money. Although I had not intended to neglect my duty and make the contacts General Hata ordered me to do, when I was about to leave, four or five of my companions held me back saying that I could stay for a few more days. They said they would take me to nice places. As we did things together the time passed by very quickly, but I was able to see many parts of Shanghai which a tourist would not usually be able to see. At that time, there were three settlements in Shanghai—the Japanese, the international, and the French. The Japanese settlement was comparatively safe as public peace and order was maintained. The most dangerous of the three was the French district.

There were many places made all the more interesting because of the danger involved. It was the second day of my stay in Shanghai that Uraoka said, “I’m going to take you to a fashionable spot in the French settlement tonight.” He then said, “We live in a world where we can’t tell when we’ll lose our lives, so I’ll take you to the most interesting place imaginable and you’ll never have any regrets about life.” We sneaked out of the hotel and went to a place called Pah Sen Chao in the French settlement.

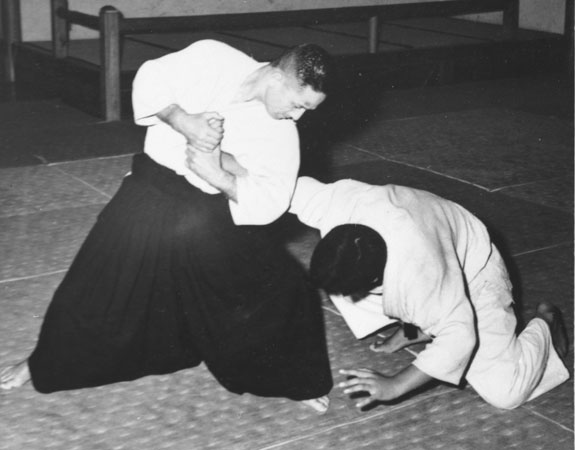

I will omit the story about the confused fight we had there and the details of my first experience in learning about the power of aikido since I mentioned it in part one. I think back on my younger days quite fondly since we could meet such challenges, display our abilities fully, and walk with a swaggering gait without apology despite such wild episodes which were a kind of training. It was then that I was the most thankful that I was taught aikido. I thanked Ueshiba Sensei and my late father who encouraged me to learn the art from the bottom of my heart. When we searched the men for concealed weapons, we found that each carried a pistol used for assassination. The pistols were made in Czechoslovakia and were of small size and delicate design. That type of weapon was not available in Japan at that time. When one uses this pistol to assassinate someone, he holds it in his hand placing the muzzle between his fingers and fires when he passes the victim. I brought back four pistols as a souvenir.

*The above article was prepared with the kind assistance of Guy LeSieur of Montréal, Québec, Canada.*

Thank You, for the opportunity to learn more of The Aikido Life I need something to help guide me in life to a form of mental comfort, I believe that thru the practice even if on my own of the Aikido Way I will reach my goal of Tranquility, again I Thank You Julian Velez