I would like to devote a few paragraphs to the profound influence of Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba (1921-1999) on aikido as we know it today. I am prompted to write at this time because I have noted an increasing ignorance of Kisshomaru’s many contributions in a shift towards a focus on the views and activities of the present Doshu, Moriteru Ueshiba Sensei, in his leadership of the Aikikai organization. This gradual change in perceptions is completely understandable as a historical phenomenon and given the passage of time since Kisshomaru’s death 14 years ago [now 20 years ago].

Why is Kisshomaru arguably the most important figure in aikido history, apart from his famous father Morihei Ueshiba, the art’s founder? Let me outline in brief the scope of his imprint on modern aikido within the context of the Aikikai system, the art’s dominant political entity.

When I met Kisshomaru Sensei in 1963 in Southern California during his first foreign visit, he appeared to be a rather shy, modest gentleman, possessed of a journeyman’s skills in the art. His soft-spoken teaching approach seemed designed to inculcate the basics of the art as taught at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo during this early time frame.

Kisshomaru was vastly overshadowed by the charismatic Koichi Tohei — parenthetically, his brother-in-law — who had already conducted numerous seminars abroad, especially in Hawaii, and was just beginning his foray into the mainland USA. Kisshomaru, by contrast, was seen primarily as the founder’s son and manager of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, the person occupied with administrative tasks. His role as an Aikikai instructor was seen as de rigueur given his position as Morihei’s son, but he was in no way regarded as a technical standout or gifted teacher in a league with Tohei.

When Koichi Tohei resigned from the Aikikai in May 1974, his absence left a huge void that had to be quickly filled for the Aikikai to maintain its prominence as the world’s premiere political body. It was at this point that Kisshomaru stepped forward to assume a leading role in all matters aikido-related, and began to actively reshape the Aikikai according to his vision while casting off Koichi Tohei’s heavy mantle.

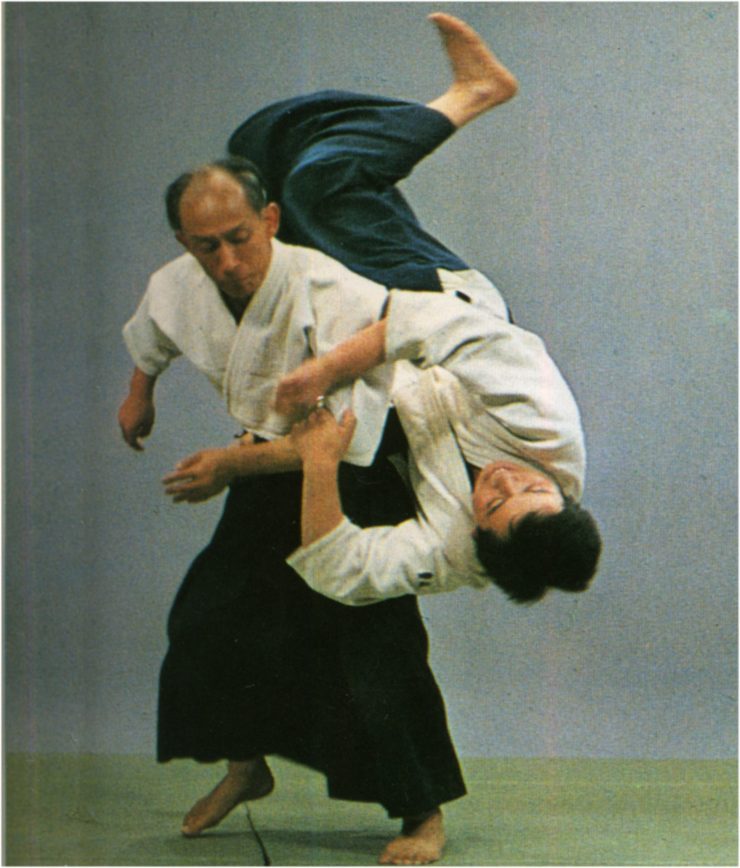

Kisshomaru’s new activism took several forms. He worked systematically to standardize the aikido curriculum, and his efforts could soon be seen in the new generation of junior instructors, young men in their 20s and 30s, whose techniques began to closely resemble those of Kisshomaru. This was perhaps no more apparent than in the grooming process of his second son, Moriteru, as the successor to his position as aikido’s doshu. Moriteru’s technique became virtually identical to that of his father, and his pedagogical approach became likewise similar. Besides serving as the model for the young crop of Aikikai instructors, Moriteru’s education would insure the propagation of Kisshomaru’s technical and pedagogical legacy far into the future.

The last half of the 1970s and 80s also saw the publication of numerous technical books authored by Kisshomaru that laid out a formal curriculum that would form the basis for technical instruction within the Aikikai network. His son Moriteru began appearing in these texts as well, initially in a supporting capacity, and later in a more prominent capacity. These books played a strong role in promoting a common teaching approach among teachers and federations within the Aikikai system.

Kisshomaru was vastly overshadowed by the charismatic Koichi Tohei — parenthetically, his brother-in-law — who had already conducted numerous seminars abroad, especially in Hawaii, and was just beginning his foray into the mainland USA. Kisshomaru, by contrast, was seen primarily as the founder’s son and manager of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, the person occupied with administrative tasks. His role as an Aikikai instructor was seen as de rigueur given his position as Morihei’s son, but he was in no way regarded as a technical standout or gifted teacher in a league with Tohei.

In a similar vein, Kisshomaru worked to create an official version of aikido history, starting with his biography of his father titled “Morihei Ueshiba, Founder of Aikido” in 1977. In addition to providing a great deal of previously unpublished material on his father’s life and the early years of aikido, Kisshomaru’s work staked out the official stance of the Aikikai on a number of sensitive historical issues. These included the following:

- the influence of Sokaku Takeda and Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu on the formation of aikido

- a Morihei-centric version of the founder’s involvement in the Omoto religion

- the minimizing of the extensive connections of early aikido to right-wing political and military figures and institutions

- the obscuring of the respective roles of Morihei’s nephew Yoichiro Inoue, Kenji Tomiki and Koichi Tohei in the evolution of the art

Kisshomaru skillfully appropriated the image of the founder disseminated by the Aikikai in the service of the organization’s views and goals for the greater aikido community. Morihei’s image served as proof of the unquestionable legitimacy of Aikikai authority, while retaining an opaque quality that resisted close analysis or alternate interpretation. Little by little, a form of “political correctness” took hold within the Aikikai system that discouraged independent historical research and publications of findings that fell outside the scope of acceptable boundaries in the portrayal of Morihei’s life and art.

During the late 1970s through 1996, I interviewed Kisshomaru Sensei for publication on about 12 occasions. I was able to witness first-hand the evolution of the Doshu’s thinking on various historical matters, and to identify sensitive areas that, for personal or organizational reasons, he chose to avoid or downplay.

Kisshomaru’s outwardly soft demeanor concealed a politically shrewd mind that he used in good stead in the furtherance of Aikikai organizational aims. During the last decade or so of his life, Kisshomaru created conditions whereby political rebels who had sided with Koichi Tohei on his split from the Aikikai could return to the good graces of the mother organization. His attitude of forgiveness where deep-seated wounds lingered will no doubt accrue to his credit on analysis by future aikido historians. Kisshomaru also had the foresight to accept various independent and disenfranchised federations into the Aikikai fold, in those instances where their size and cohesiveness met the necessary criteria.

Kisshomaru skillfully appropriated the image of the founder disseminated by the Aikikai in the service of the organization’s views and goals for the greater aikido community. Morihei’s image served as proof of the unquestionable legitimacy of Aikikai authority, while retaining an opaque quality that resisted close analysis or alternate interpretation. Little by little, a form of “political correctness” took hold within the Aikikai system that discouraged independent historical research and publications of findings that fell outside the scope of acceptable boundaries in the portrayal of Morihei’s life and art.

By the 1990s, Kisshomaru’s status as the aikido world’s predominant figure had become cemented within the Aikikai sphere of influence. The unassuming, bespectacled son of Morihei Ueshiba had transformed himself into a force in his own right, and begun to receive fawning treatment wherever he went. Now an elegant, grandfatherly-like figure, he wielded unquestioned authority in all matters concerning the governance of the art within the Aikikai dominion. Kisshomaru’s stamp had been firmly impressed on aikido, and its future influence guaranteed for at least the next two generations through his son Moriteru, and grandson Mitsuteru.

Just as many Kata rely on a shorthand with a good structure of instructors that can unravel the mysteries of the art, so too aikido needs that structure. Even if the meaning is forgotten, with proper notes and a sound practice that can be interpreted many ways but also works on a practical level, aikido does still contain the sound structure that can be unraveled from the short hand that appears to be the safe practice, and yet if one studies the old battlefield arts of war the old injuring techniques are easily found because the shorthand still is able to be understood.

Indeed, we owe a great debt to the Second Doshu of Aikido for not only navigating the waters of human ego, but also giving us all a set of notes that are both a practical martial art but also a wonderful practice of body, mind, and spirit that transcend human ego. If we were to simply practice the standard format of Aikido, the notes he has left would still be clearly interpreted for centuries to come.

I would ask, are the notes of practice YOU leave for your students and fellow practitioners … good enough?

I am always amazed that people in different styles of Martial arts think their style has something that is not in the shorthand notes of other styles, it isn’t. If you study and look … all the same pressure points and angle of attacks are found in all styles, but some styles concentrate on the beat of movements, much like music, that work for that style. Sooner or later everyone discovers .. they need to study all styles of arts to understand their own particular style.

To be clear, you don’t have to spend years practicing different styles, but you need to STUDY to understand what the shorthand really means. Many people in Aikido know the physical side of what works for aikido practice but never study how it is incomplete because … it is shorthand for a practical battlefield application that is so much more…. then again .. a few people do.

Remember, Aikido is a safe PRACTICE … not the true application, and for those notes of practice … we must thank the Second Doshu for giving us structure and organization.

quote “Remember, Aikido is a safe PRACTICE … not the true application” end quote…..

Really????

If Aikido`s true application is not practiced, no matter how much note taking one does, one will simply fail when it is needed/required. I find this statement deeply disturbing and a major concern.

Politically correct, molly cuddling, sterilized padded safety, non application, has absolutely nothing to do with the safe practice of martial arts. If this is the case its just dancing and not a martial art at all.

Totally shocked,

Andy B

I was only privileged to study with the 2nd Doshu in one seminar. He brought an uke who trashed our local tough guy, Bruce Klickstein, and yet was turning beet red & dripping sweat while struggling to escape an intermediate position in ikkyo which Doshu was holding easily while explaining it.

History is always “the winner’s propaganda”. In this case Doshu’s legacy includes a viable curriculum and teachers familiar with it. That honors his father’s legacy and provides a clue as to O Sensei’s art. The number of gifted martial artists is large. The number of schools that survive their founders is not. The survival of aikido into the third generation probably has more to do with its management in the second than the brilliance and inspiration of the first.

As to giving those of us who are ignorant of Japanese and have not been privileged to visit Japan an idea of our roots, I would like to thank our host Stan Pranin sensei.

Mr. Warren,

This is off subject, but your telling of Klickstein being handled so by Nidai Doshu’s uke is one of those great little stories that one never gets to hear about, and I find it interesting. Recently, some video has surfaced of Klickstein teaching Aikido. About two hours worth. A casual search on youtube will show it. Of course no one is talking about that at all either.

Dear all,

I would like to introduce myself and name is Nay Myo from Kokorozashi Dojo of Myanmar Aikikai New Organization.

From my point of view, Aikido is a way of teaching to get killing your ego and way of understanding the true martial arts.

We may have the different ideas from the different point of views but firstly we have to practice Aikido to understand the attitude of Aikido and we have to consider what we are doing and where we are going.If you get this point you may know something mysterious and you have to keep practicing with your new knowledge about mysterious.

If you are practicing Aikido in this way, you will become the true soul of martial art.

My practice of Aikido is a way to get harmony between mental and physical skills development.And its allow our mental to be strong and gentle.

World is complex,life is more than that.But Aikido show us the way to be suited with our life to the nature.That is why AIKIDO is called PEACE of ART.So I thank to O Sensei and both of Doshu because O Sensei leave us his unlimited Philosophy which is positively developing the community and universe.

Thank you for reading and look forward further discussion.

[email protected]

Regarding Stan’s description of Kisshomaru Ueshiba leaving a forceful and lasting influence on aikido history and future practice through his son and grandson, I recently noticed on the Aikikai Foundation website the removal of Isoyama Shihan from the Dojo-Cho position at the Ibaraki Branch(Iwama)Dojo, and appointment of Moriteru Ueshiba and his son as Dojo-Cho. It would be facinating to have Stan’s perspective on the implications and ramifications of this change.

Just found this on line.

http://cultofaraluen.com/2011/01/17/interview-with-waka-sensei-moriteru-ueshiba/

[…] Il nous livre un article sur l’empreinte de Kisshomaru Ueshiba,fils du Fondateur. La source de l’article est en anglais sur le site du Aikido Journal,dirigé par Stanley Pranin. Nous avons traduit aussi […]