The popularity of aikido, both in Japan and abroad, is a post-World War II phenomenon. Early students of Founder Morihei Ueshiba, such as Koichi Tohei, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Gozo Shioda, Kenji Tomiki and others, followed by their students in turn, were mainly responsible for the growth of the art on an international scale.

What factors are responsible for aikido’s broad appeal? Many people observing the art for the first time comment on the beauty and gracefulness of aikido techniques. The attacker is thrown in a seemingly effortless manner yet suffers no apparent harm from the encounter. The promise of a self-defense art that protects the individual while sparing the aggressor is an attractive concept in philosophical and moral terms in a world where the specter of warfare seems ever present. Aikido’s ethical basis appeals to man’s deep-seated instinct for survival. At the same time, the art provides a unique alternative to the violent techniques of other martial arts—techniques that elicit moral repugnance in many.

On a physical level, aikido has much to offer for the health conscious. The accumulated benefits produced by warm-up, stretching, throwing and falling exercises are considerable. Many practitioners have undergone dramatic physical transformations through aikido training on their way to a fitness lifestyle.

The social milieu that develops in aikido dojos is an important part, too, of the training experience for many practitioners. Aikido tends to draw from a wide age range and students continue longer than practitioners of arts centered on competition, primarily the domain of young people. Also, I think it would be accurate to say that, as a percentage, aikido has a higher ratio of female participants than any other martial art. All of this contributes to a strong sense of community. For many students of aikido, the dojo is an extension of or even a substitute for their family.

Aikido: the non-martial art

For all of the positive benefits of aikido training, the art has not yet realized its great potential as a social force for promoting harmony among people. Although the relationship may not appear obvious, I think this is due in large part to the art’s distancing itself from its martial roots. It is the martial atmosphere of the dojo setting that allows students to develop real-world skills and elevates the level of training beyond that of a mere health system. The neglect of the martial side of aikido can be explained in part by historical circumstances.

Japanese society in the postwar era rejected the military mentality that led to the country’s involvement in the Second World War. Given this inhospitable climate where the practice of martial arts was forbidden for several years, the martial nature of aikido was suppressed. As a consequence, what remained of the art that was embraced by hundreds of thousands of practitioners was—with few exceptions—something quite different from the original concept of the Founder. The techniques of aikido retained only the outer form of a martial art and tended to be practiced in a setting devoid of martial intensity. Let us look at some of the factors that cause aikido to fall short as a martial art.

Weak attacks

The root of the problem as I see it lies in the weak attacks that are commonplace in aikido dojos nowadays. Students are seldom given training in how to execute an effective attack, be it in striking, grabbing or the occasional choking or kicking techniques. The situation is further exacerbated by a lack of committed intent or focus during attacks. This absence of firm intent on the part of the attacker affects his mental state and that of the person executing the technique. Both sides are aware—at least subconsciously—of the minimal risk of injury in training under these circumstances. Accordingly, the focused mind-set needed to develop realistic self-defense skills is absent from training.

Neglect of atemi and kiai

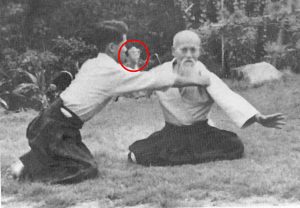

A study of the art of the Founder will reveal his emphasis on atemi (preemptive strikes) and kiai (combative shouts) as an integral part of techniques. O-Sensei can be seen executing atemi and kiai even in films from his final years when his aikido had become much less physical.

Atemi and kiai go hand in hand and are important tools for stopping or redirecting the mind of the attacker and successfully unbalancing him. Even if a physical strike is not actually employed, a mental state that preempts or disrupts the attack is a vital component of the aikido mind-set. Yet in many dojos today, the use of atemi or kiai will draw scorn from the teacher in charge who regards them as crude, violent means that have no place in an art of “harmony.” This common misconception bespeaks a lack of understanding of the martial origins of the art and the theory and practice of the Founder.

Failure to unbalance attacker

The combination of weak attacks, lack of atemi and kiai in aikido practice lead inevitably to practitioners attempting to execute techniques without first unbalancing the attacker. An uncommitted attacker having foreknowledge of the technique to be applied is not easily brought under control. This introduces an artificial element of collusion into the interaction between practitioners and results in a training atmosphere that is fundamentally different from the intensity of a real encounter.

Use of force and “make-believe” throws

The logical consequence of the above training lapses is the execution of sloppy, imprecise throws and pins. Since full control of the attacker is not achieved, it often becomes necessary for the person throwing to resort to physical strength in order to complete the technique. This leads to clashing and raises the risk of injury.

Another scenario is that neither of the two partners put any serious effort into the technique and the interplay between them is little more than choreographed collusion.

The progress of practitioners taught in a setting in which the “martial edge” is absent and where sound training principles are not observed will necessarily be retarded. What is worse, some who are products of this kind of training environment will entertain the illusion that their skills would be viable in a realistic situation.

Premature physical decline of instructors

I suspect that a certain segment of the aikido population would agree with the above observations. On the other hand, the next subject I will broach will no doubt elicit controversy in many quarters.

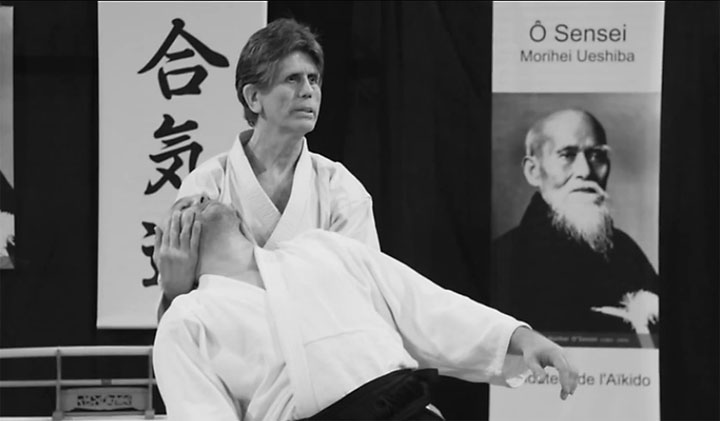

In my 40 years of involvement in aikido I have observed numerous teachers pass from their physical primes to a state of declining health and, in the cases of some, to an early demise. All too frequently they have accelerated the inevitable aging process through poor lifestyle choices. As their bodies age, teachers frequently adapt their techniques to compensate for their physical ailments and decreased ability to move. Moreover, they stop engaging in “give-and-take” practice where the roles of uke (the attacker) and nage (person throwing) are alternated. They become “teachers,” but cease to be “practitioners” in the way they were in their formative years of training.

The withdrawal of teachers from partnered training practice whether or not the result of a conscious decision has far-reaching effects on their aikido careers. By no longer doing warm-up exercises and taking falls, they undermine their level of body conditioning and flexibility. Focusing exclusively on throwing contributes to a overall weakening of the body structure and muscular tone and invites injuries.

As teachers seldom practice with their peers beyond a certain point in their training, an artificial cap is placed on their progress because their pool of training partners is limited primarily to their own students who are almost always of a lesser skill level.

For all of the positive benefits of aikido training, the art has not yet realized its great potential as a social force for promoting harmony among peoples. Although the relationship may not appear obvious, I think this is due in large part to the art’s distancing itself from its martial roots. It is the martial atmosphere of the dojo setting that allows students to develop real-world skills and elevates the level of training beyond that of a mere health system. The neglect of the martial side of aikido can be explained in part by historical circumstances.

Remedies

Much of what needs to be done to restore the martial nature of aikido in accordance with the vision of O-Sensei involves correcting the poor training habits alluded to above. Here is a list of concrete steps than can be taken that would literally revolutionize aikido and restore its great potential as a force for social betterment.

Teaching attacking skills

First of all, great attention should be given to teaching aikido students how to attack effectively and with resolute intent. This may require some teachers to engage in cross-training of some sort in order to acquire the necessary skills themselves.

What kinds of attacks should be introduced in the aikido dojo? This will be a personal decision on the part of the instructor in charge. I think that basic punching skills from karate, boxing or other sophisticated systems should be considered.

Students should also become familiar with kicking at least at an elementary level. Although not as prevalent as punches, it is quite possible that one might be confronted with kicks in a real encounter.

Learning defenses against kicks also helps students overcome the common problem of “tunnel vision.” For example, beginners tend to focus their attention on the initial, overt aspect of an attack—usually a punch or grab—and fail to recognize the possibility of a secondary attack. When students realize that they must consider another attack such as a kick may be forthcoming, their state of alertness improves.

The withdrawal of teachers from partnered training practice whether or not the result of a conscious decision has far-reaching effects on their aikido careers. By no longer doing warm-up exercises and taking falls, they undermine their level of body conditioning and flexibility. Focusing exclusively on throwing contributes to a overall weakening of the body structure and muscular tone and invites injuries.

Learning how to kick properly will also improve the falling skills of aikido students because falls from kicks are more difficult and dangerous. Care should be taken to proceed slowly because the risk of injury is higher.

Among the existing aikido systems, Yoseikan Aikido developed by Minoru Mochizuki takes this sort of eclectic approach that incorporates elements from several arts. Students of this system are taught basic karate, judo and weapons skills as part of their training.

Beyond this, one might want to introduce attacks involving weapons—both bladed and non-bladed. Training with weapons is a useful tool to teach the importance of maai (distancing) under different circumstances and offers many other benefits. The Iwama Aikido curriculum of Morihiro Saito is an example of a systematic approach to weapons training.

The end result of improving the quality of attacks will be a greater focus during training and the creation of an atmosphere of seriousness and respect for one’s partner. The risk element always present in martial arts training will be recognized and due care taken to avoid behavior that leads to injuries.

Bringing back atemi and kiai

The use of atemi and kiai should be reintroduced and encouraged in aikido dojos. Atemi and kiai are extremely important in that they may allow a practitioner to overcome physical or numerical superiority in a real encounter. They are invaluable aids in neutralizing an attack and unbalancing an opponent. They pave the way for aikido techniques to be applied without force and against little resistance.

It should be possible to apply atemi or use kiai at virtually any stage of an aikido technique, not just the beginning. Students should be coached on how to recognize an opponent’s openings at every opportunity. Shoji Nishio has developed atemi skills to a high level and his martial-form of aikido is a valuable reference.

At a higher level, atemi may not even have a physical manifestation. An advanced martial artist can achieve the effect of an atemi through subtle body language alone as long as a mind-set preempting the attack is present. If you watch films of O-Sensei carefully you will see this principle in operation and it is a key element of so-called “no touch” throws.

Keeping the attacker off balance

A fundamental yet often neglected principle of aikido is the importance of unbalancing an attacker and maintaining control from the beginning of a technique to the decisive point involving a throw or pin. I have often observed techniques being taught to students where the attacker’s balance is first taken only to be given back immediately before the throw!

One only has to carefully observe the center of gravity of uke to determine whether or not his balance has been taken. Students should be constantly vigilant of their partner’s center of gravity in order to determine if their techniques are being effective.

Before leaving this subject, an interesting exercise when attending an aikido demonstration is to watch the movements of uke rather than nage. If uke‘s balance is being controlled throughout the technique then you are observing a true master.

Posture and breath control

Other areas that are often overlooked in aikido training are correct posture and breathing. Nage should cultivate good posture and keep his balance throughout the technique.

Attention to breathing habits is seldom stressed in dojo training. By pacing your breathing it is possible to create and maintain an internal body rhythm that will reduce fatigue and make it easier to keep one’s composure under the stress of vigorous training. Learning to observe one’s own breathing will also develop the ability to “read” an opponent’s breathing. This is useful to sense the timing and intent of an attack at a stage prior to its physical manifestation.

Instructors should get back into training

The most common reasons given for aikido teachers ceasing to participate in normal dojo training are the limiting effects of aging and the accumulation of injuries. It is certainly not possible for anyone to escape the effects of time and the wear-and-tear on the body of vigorous aikido training.

This being said, there is nothing to prevent teachers from training within their individual limits and at their own pace. As I see it, the key element is to continue to do stretching, warm-ups and take falls to the extent possible. You either do it or you don’t!

The Founder maintained his suppleness well into his 80s and was even capable of doing the splits. Also, he can be seen taking falls for a child at about age 79 in one of the surviving films.

In many kobujutsu schools it is the custom for the teacher and seniors to assume the role of attacker and take falls for junior students where required. You will see this if you attend a demonstration of classical martial arts. Imagine for a moment how it would change things if the top aikido instructors were capable of and actually took falls for their students during demonstrations! And what better way than this would there be for teachers to accelerate the improvement of their students?

I truly believe that it is possible to add ten good years to one’s aikido career by adopting the approaches suggested here. I’ll let you know in about 20 years time how this theory works out in my personal case!

Cross-training

I think one of the most positive things that instructors and practitioners alike should consider is cross-training in other arts. Here again we can look to the example of O-Sensei who studied a number of martial arts in his lifetime. He also arranged for the marriage of his daughter to a famous kendo expert and allowed a kendo group to form and practice in the old Kobukan Dojo. At age 54, the Founder formally enrolled in the Kashima Shinto-ryu, a classical school with a several-centuries-long tradition. He drew heavily from the Kashima Shinto-ryu curriculum in developing his aiki ken. O-Sensei also invited masters of other arts to the Aikikai Hombu Dojo to visit and give demonstrations. He was always prepared to “steal techniques” from other experts through keen observation.

One of the prime purposes of the annual Aiki Expo event sponsored by Aikido Journal is to encourage and facilitate cross-training among different groups.

See an example of how the new Aikido Journal continues the tradition and spirit of the Aiki Expo events.

Conclusion

I have attempted to explain how what is accepted as “modern aikido” is really a permutation of the original concepts underlying the aikido of the Founder. Due to the considerable spread of the art in the postwar Japan and abroad and the passage of more than five decades, these changed forms of aikido have come to be considered the norm. The assumption of most is that these new approaches reflect the intent of the Founder whereas, to a large degree, this is not the case. Most of the criticisms of aikido today arise because the modern forms of aikido have strayed from the Founder’s main precepts. The suggestions offered in this article would, if adopted by a significant section of the aikido population, produce a major change in the quality of the art and how it is perceived by skeptical outsiders. It is our intention to lead the way toward this desirable end by organizing future events such as the Aiki Expo.

Stan,

Good stuff, I have very little experience with “Aikido” in the brand-name sense of the word but sensed these issues from contact with practitioners and the content of the posts on your site. I posted a piece here some years ago about the difference between big-A Aikido and the stripped down meaning of 合气道 and its universality within the martial arts. As an outsider who ironically has practiced some of the same arts as your Founder but has only once walked into a “Aikido” dojo I would suggest getting away from the kind of rigid cult mentality that seems to plague practitioners of many martial arts. My feeling about this echoes your call to cross-train but goes beyond since I think when you talk of “cross training” the sense is that one is still “inside” a particular style identity or box, when I would recommend not taking “Aikido” in the brand-name sense as THE WAY that is somehow correct over and above other ways. Instead just take Ueshiba’s philosophy and method as one of many examples of the ultimate aim. I don’t think Ueshiba was unique in the larger world of martial arts except in that he was able to articulate certain ideas in a way that was spread and had people who were good at organizing. If you remain as an “Aikido” practitioner then you are automatically committing your ego to certain identifying attitudes and practices which may or may not be the most expedient method of attaining the goals espoused by your founder. Ueshiba never learned “Aikido” from anyone so why should I if I aspire to something like his ability and outlook on life? It seems silly to take the culmination of one man’s diverse life experiences as a rigid path that one must follow for that goes directly contrary to the method actually practiced by that man himself.

So because of this (and it is an issue across the martial arts world) we get all sorts of distortions and rigidities in practice. As you said, many of your Aikido ilk do this un-committed, fuzzily-intentioned kind of training. The same can be said of people who tend to work more within the Chinese methods like taiji. They probably fall into this trap even more than you Aikido folks. Then at the other extreme you have the Hapkido folks and a lot of the “hard” arts where they avoid fuzzy intention but by over-emphasizing fast, strong, aggressive movements even at early stages of practice, resulting in stiff and injured bodies and difficulty in mapping the sophisticated motor programs that underlie true skill. This is a problem on both sides. Most Aikido folks have this idea of “peace” without really understanding what it means and so just kind of shuffle about slowly without really engaging. The other folks, I’ll stick with the Hapkido example since they’re kindred schools, they are worried about being “effective” and so go too fast, too aggressive instead of slowing down and noticing. I’ve also seen this within my current Chinese circle. Some folks do the kind of awkward rolling the body around without the kind of precise, route-mapping, spinning sphere movements that develop true skill, others, fearing that moving slowly at all is useless, move in fast, sharp, aggressive ways that only serve to tire and stiffen the joints while inflating the ego with illusions of effectiveness. It is in fact very difficult to find that golden path through the middle of these two extremes and I think the rigidity of group-think and the social pressure to remain within certain idealized norms only serves to inhibit the natural back-and-forth oscillation of the practitioner’s individual journey to find that “sweet spot”. I would suggest to Aikido folks and anyone in the martial arts to abandon the frames of “right and wrong” which end up in these calcified organizational structures with their tendency towards doctrinal thinking.

The reality is that there is such a range in possible training methods and different approaches are appropriate to different ages, stages, body types and personal tendencies. Some people are naturally timid and should be encouraged to be strong and fast and competitive to increase their self-confidence before then being guided towards softer, more gradual mapping methods before then being pushed towards more structured technical training. Some folks are naturally aggressive and so should be started on the quiet, soft and disciplined before being reintroduced to work involving contact. This is just my personal feeling from the variations in my own training. I find that the Systema folks do a good job of this but I also find that their underlying philosophy can also lead to tunnel vision within their practitioners. While I feel very comfortable training with Vladimir and others at the Toronto school while visiting schools in other parts of the world I have encountered a kind of fascistic mentality which infiltrates their satellite schools. The practitioners in such an environment will inevitably have their progress curtailed by calcified mentalities, whether it’s a calcification of a vacuous “peace” or a paranoid macho pursuit of “control.” Martial artists are just people with the issues of greed, ambition and the desire to dominate just like everybody else. What marks them off from each other is the different expressed ways they pursue the ambitions of their troubled psyches. There is no way to mitigate against this for the individual except to recognize this and not allow oneself to be too much under the sway of one person’s psychic disequilibrium. It’s hard enough to overcome your own obstacles without worshiping those of another.

I would counsel to any practitioner to develop an eye for movement and an openness to alternative approaches, to sharpen one’s visual discernment and then maintain an open mind. For example, the Chinese methods lack the kind of structure and intention of the Japanese methods as well as the “fullness” of the techniques, tending towards repetitive, toned-down drills. The advantage of these methods though, is their portability and ease of practice. While practicing a full Aikido or Jiu-Jitsu technique in a park will like damage your clothes, expose you to injuries from ground debris, make passers-by uncomfortable and possibly provoke a response from law enforcement, the more toned-down, game-like partner practices in Chinese traditions provide some useful practice involving contact and joint locking but are suitable for practice almost anywhere you have “space for a cow to lie down.”

The Systema folks have excellent conditioning methods which are a really good basic-training foundation for any approach but which, like Japanese arts, involve a lot of ground-work and so are only suitable for practice in larger spaces, preferably with some kind of padded flooring. Their progressive methods are really great for developing real understanding but I find that oftentimes there is little chance to really work on solid techniques. I know their method is anti-technique and I understand why but sometimes the sort of strict Japanese approach of getting the angle and approach “just right” can yield a great deal of insight in training.

The Chinese approach if used on its own threatens to devolve into very collusive and sort of “floaty” practice without true skill but if tempered by the insights gained through more vigorous structured practice can yield a fundamental basis for greater physical awareness that will allow learning techniques to progress much faster. Being able to slowly map out basic body structure through 功 training can make the difficult-to-perfect locks of jiu-jitsu techniques easier to solve and things like delivering proper, loose strikes more natural.

My point is that to truly follow the path laid out by your Founder, a more flexible mindset would be a great asset. So long as one speaks of “cross training” one has the right idea but the very notion means that you are remaining within a certain fixed path and necessitates a certain degree of mental calcification. Instead of seeking to perfect “Aikido”, it seems expedient to seek to understand movement and the “taste” underlying your founder’s skill and then be prepared to undertake a constantly evolving approach to training that may see you taking very different and mutually contradictory approaches at different times depending on one’s inner intuitive sense of what is needed at the time. My own practice has evolved in this manner and from my reading of your Founder’s life, he also pursued this method. Perhaps at heart the challenge for Aikidoka is to spend more time following the life of your Founder and less energy on following the dictates of the organizations and cliques which profit from his legacy.

At the risk of being accused of using a sound bite to encompass a complex issue, I do see the principle of ‘peace through strength’ as applicable. Weak, ineffective techniques do not convince your attacker, and so don’t lead to compliance and teaching. Now I want to respectfully boast.

For the past year and a half I’ve had the luxury and privilege of training 5+times a week with a sensei who has extensive cross training in Okinawan styles, weapons, and swordsmanship (iaido and cutting ‘battoh). He was a direct student of both Saito Sensei and Nishio Sensei (that latter promoted him to 4th dan). This has spoiled me on the principles you discuss. He takes more ukemi that many can tolerate who are half his age. We always warm up even after a 30 minute break between classes. Most importantly he doesn’t espouse that he has THE way. Only that he has had great teachers and sometimes finds very subtle elements within techniques even after decades and that we should be experimental with those subtleties to see if they stand up to scrutiny. If they do they get carefully used alongside the ‘original’ technique and after a while it becomes clear that these ‘discoveries’ were probably in the techniques of O-Sensei all along but not easily discerned. And if some are truly new that is consistent with OSensei’s intentions. When I have encountered others who don’t have this background, their techniques are ineffective because they fail to unbalance, use no atemi and break off a technique in the middle of execution because the attacker is not attacking right! (I am referring to dan level practioners).

Kyrinov’s comment is an insightful article in its own right. Thank you both for your applying your experience and scholarship to keeping alive the martial in the art of Aikido.

Kyrinov….HERE….HEAR!

Thank you so much for this article. Many in the Aikido community won’t like what you said but the truth hurts. It has bothered me for some time watching Uke attack with slow, soft and sloppy attacks, even stopping half way through the attack if Tori isn’t ready to defend- how sad is this. No one on the street is going to stop during an attack because you have your back turned, but we do it all the time in practice, especially in randori. If we want our students to be able to defend themselves on the street, we need to practice against punches to the face, kicks and knife and gun disarms.

I aggree with your point on teachers who stop training and only teach. I recently had back surgery and just started teaching again, but can’t take ukemi or even stretch at this time, nothing but rest. I miss taking ukemi from my students because not only does it continue my training, but the most important part of taking ukemi from students is that it allows me to feel how my student is performing the technique, and if there is something wrong, I may not see it when watching only but will feel it when being uke.

I hope after the initial anger wears off, that instructors and students alike will take this article to heart and see the problems currently facing our art. There is nothing martial about an art where uke attacks with shomen uchi or yokomen uchi all the time and it comes at you slow, soft and sloppy. An art where randori is a game of tag for uke and hide-n-seek for tori.

Panda sensei

Stanley,

I agree with your article 100%.

Our dojo had the priviledge to have several highly skilled martial art students of several different martial arts as members. The mentoring of these people took our Aikido to a realistic level. Allowing these people the opportunity to contribute is all that was required. The final ritual of every class is to form a circle and bow together in honor of the group effort in teaching.

Ueshiba’s observational “stealing techniques” from other masters is the only way to learn the techniques of the masters. Knowing what to look for is the key to “seeking.” Also, their vocal teachings usually falls on deaf ears; so I believe they just give up.

Yet, to sort of contradict myself, there is a place for the really soft approach within Aikido to allow a place in Aikido for everyone. Aikido’s possibilities/potentials are too great to place limitations on its appeal. “AI” is powerful stuff. My Sensei, Kancho Utada says, “Aikido is for all.”

Thank you for this article by Stanley. His dedication was admirable.I love the art and practiced for 4 years during the Tohei era. When Ki was king.No mention of that at all.:( Partly because to teach it , it is hard.. Aikido should start with self defense moves first and then learn more kata based techniques. Like many martial arts it is backwards. Also he mention kicks.Rarely do kicks happen in fighting. haymakers and tackle more likely. That’s where we should training the most.A great forgotten tool of aikido for this is the ”unbendable arm”. I have never seen it used in aikido setting to defend and have seeing it in non aikido fighting. thanks Josh for keeping the art alive it is beautiful ritual combat.

A challenging article that is on point. I have seen many teachers reach a stage where their students – out of misplaced respect – no longer attack with commitment. It is then tempting for the teachers to start thinking they are invulnerable, and they possibly become arrogant.

A balance needs to be found between letting the students experience vigorous and intense attacks and defences, and yet allowing them safe space to contemplate the subtle aspects of how mind can influence the shape of the technique.

As any experienced aikido practitioner knows, developing subtle awareness of “directions of ki” is essential for developing an understanding that the Founder had. Uke needs to enable this exploration through simulating commitment while protecting themself. This is not obvious to “YouTube practitioners.” 100% “real” attack is not possible in aikido as it could be dangerous. For instance, a well-executed ikkyo could break the back of a fully-commited attacker.

Somehow, the teacher needs to instil “reality” into beginning students while ensuring they are safe. This is a hard task. Just yesterday I was discussing with another teacher how lower grades need to treat wooden weapons as if they are real weapons, so that when they do start practising with live blades, they have acquired a sense of space and where their hands should be in disarming techniques.

On the other hand, it is my sincere belief that we need to get away from the hard and dangerous teaching methods of some well-known teachers, as inflicting injury on students is not acceptable.

I believe this article is timely, and a sensible call for instructors to review their attitudes and clarify what it is that they are trying to teach.

Excellent and very useful article to remind of basics.

This was a very interesting article and very true. This article hit home for me on so many levels. Iam a practitioner of yosokian aikido in shelby nc my job keeps me away from my family at the dojo alot.I love to practice aikido I just wish there was away to practice with real world scenarios with the same adrenaline and pain of being able to recover from a punch or kick. That being said since iv been practicing now for 4 years I’ve had great success with my weight,flexibility and general all around way I see things in my world outside the dojo and I will continue to as long as iam able or the good lord calls me home. Thanks you for these articles and research that you do for the Aikido community.