This is the third of a three-part article. Read the first part here and the second part here.

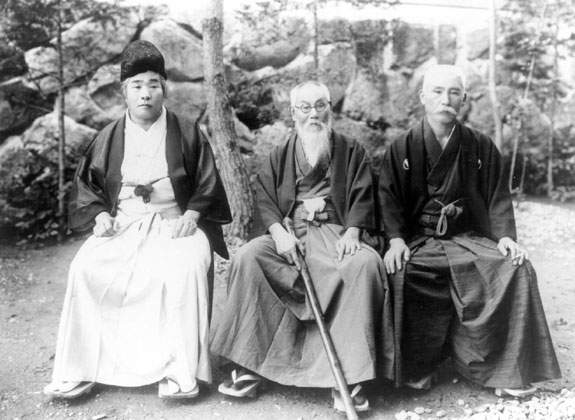

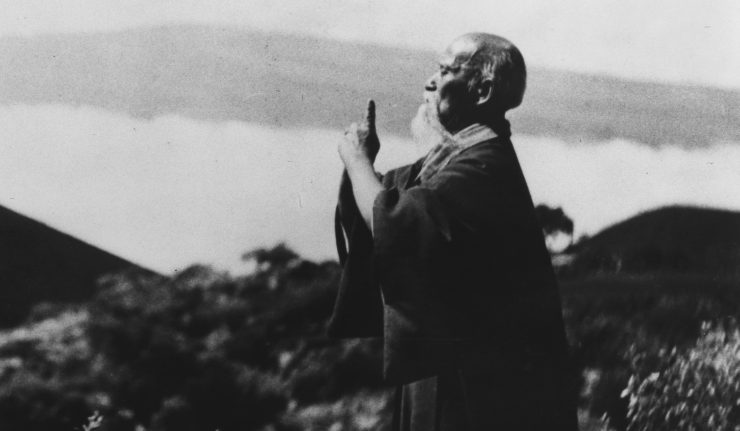

Onisaburo was a phenomenon in many regards. He was very well read and educated in esoteric Shintoism. He was a shaman, psychic, healer, and exorcist. He was a prolific author, poet, a gifted speaker, calligrapher, and ceramist. Onisaburo greatly expanded the publishing organs of the Omoto sect, and even purchased one of Japan’s largest newspapers to further his agendas. Added to these many talents, Onisaburo’s behavior was at times outrageous and provocative. He was constantly at odds with government and religious authorities, a practice that would lead to the suppression of the sect on two occasions, in 1921 and 1935. The latter event effectively destroyed the Omoto sect as a powerful social force.

In Ayabe, Morihei soon earned the trust of Onisaburo and little by little became a member of the religion’s inner circle. Onisaburo also became aware of Morihei’s superb skills as a martial artist and encouraged him to teach and develop himself further. Onisaburo had succeeded in adding a man of budo to his growing entourage.

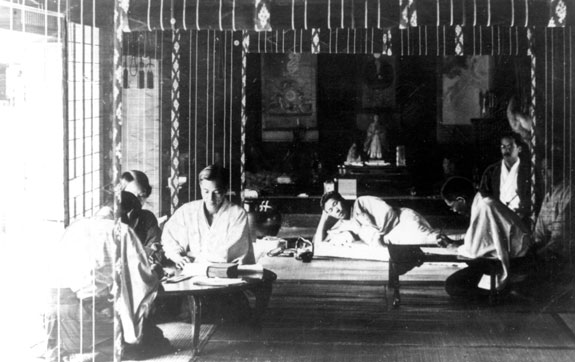

At Deguchi’s urging, Morihei set up a private dojo in his home just outside the sect’s precincts. Many Omoto believers became Morihei’s students. The “Ueshiba Juku,” as Morihei’s dojo was called, effectively launched his career as a martial arts teacher. The bond between Morihei and Onisaburo grew ever closer.

Morihei was heavily influenced by Deguchi in a spiritual sense. He studied Onisaburo’s teachings and interpretations of such things as the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest creation story and somewhat akin to the Bible, and kotodama, the ancient belief in the mystical power of sounds and language. He further learned breathing and meditative exercises such as the “chinkon kishin.”

Morihei himself credited his years at Omoto under Onisaburo and his intensive ascetic practices as the reason for the deepening of his martial skills.

Morihei was living in the Omoto community when Onisaburo began his voluminous masterwork, Reikai Monogatari, or “Tales of the Spirit World.” This 81-volume narrative work was begun in 1921 after Onisaburo had been released from jail following the first Omoto suppression. He dictated its contents in the morning before arising while still reclined in his futon. A team of scribes would transcribe Onisaburo’s speech and then edit the text based on Deguchi’s corrections. The Reikai Monogatari is an eclectic work detailing Onisaburo’s spiritual experiences and contains novel-esque passages, poems and essays. It is considered a sacred text of the Omoto religion and offers as well a great deal of social commentary and prophecies.

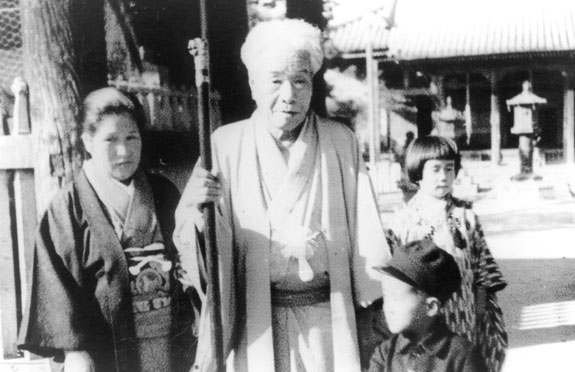

After his delayed arrival in Tanabe, Morihei’s father had already passed away. Despondent and humiliated by his late arrival, Morihei entered a state of deep depression. His escape from this dark period was his decision to move with his family to Ayabe to be at the side of Onisaburo and his followers, and seek spiritual solace. This is where the religious phase of Morihei’s life really begins, and it is closely related to the later emergence of aikido.

The government was closely watching the content and progression of Onisaburo’s prolific writings that sold hundreds of thousands of copies. The authorities would later cite passages from Reikai Monogatari as proof of the sect’s anti-governmental activities, terrorist intentions, and opposition to the Imperial order.

As can readily be seen from the above, the religious and spiritual activities of Onisaburo and the Omoto invariably spilled over into the political realm with major consequences. For his part, Morihei was in the thick of things, so to speak. Ironically, his desire to lead a secluded life of introspection and simplicity thrust him in the middle of much political turmoil and would soon place his life in grave danger.

Fast forward three years to 1924, and we once again find ourselves back at the story of Morihei in Mongolia in 1924 as the bodyguard of Onisaburo Deguchi. This time we have reached this point of our narrative through the gate of religion, and found ourselves in the same place.

Earlier we saw that Onisaburo, Morihei, and their party entered Mongolia as the leaders of a self-proclaimed “Mongolian Independence Army.” Onisaburo styled himself as a Buddhist and “Dalai Lama” on this occasion to serve his immediate purposes. The realization of Onisaburo’s religious aims in northern China included military adventurism and collusion with various unsavory characters. This sort of activity led to the termination of Onisaburo’s expedition and nearly cost the party their lives.

Onisaburo had a calculating and opportunistic side to his nature. After the party’s return to Japan, he and his party were thrust into the public spotlight due to the intense coverage of the media of their Mongolia adventure. Some scholars have even advanced the view that the leaders of the Kwantung Army essentially adopted Onisaburo’s plans for the creation of a Utopian nation with the establishment of Japanese-controlled Manchukuo.

At Deguchi’s urging, Morihei set up a private dojo in his home just outside the sect’s precincts. Many Omoto believers became Morihei’s students. The “Ueshiba Juku,” as Morihei’s dojo was called, effectively launched his career as a martial arts teacher. The bond between Morihei and Onisaburo grew ever closer.

Bolstered by his increased notoriety and a surge in growth in membership in the Omoto sect, Onisaburo continued his associations with ultranationalist and military figures and strengthened his rhetoric in opposition to many political policies of the day.

This all culminated with the Second Omoto Incident of 1935 when the Japanese government brutally suppressed the Omoto and finally put an end to this shrill voice that was constantly challenging their authority and ruling of the nation. Onisaburo, his wife, and many church leaders were arrested, imprisoned and tortured. Plans called for Morihei to be detained together with them, but he was able to escape arrest due to his powerful connections in the Osaka police department.

This fascinating religious experiment growing out of traditional Shinto beliefs and rituals met its demise by venturing too deeply into the swamp of politics and militarism. On occasions, it resorted to the use of violence and coercion, and entered into unholy alliances, thus crossing the moral line. It is unlikely that Morihei fully understood the implications of what had happened to the Omoto religion in 1935. He would, however, later come to realize how power and influence bring with it the necessity of a moral compass if self-destruction is to be avoided.

By this time, Japan was far along its path of military intervention and conquest in Asia. It proved incapable of living up to its rhetoric of becoming a model for the world of pacifism and universal brotherly love (jinrui aizen) as evidenced by the horrific outcome of the Great Pacific War. Morihei would soon come to realize that Japan’s election of war set it on a mistaken path, one inevitably leading to the destruction of the instigator. And Onisaburo Deguchi was correct is his view that the kami would punish those who resorted to violence to achieve their aims.

In contrast, aikido must focus on its mission of peace and become a model for other martial arts to transform themselves into instruments for promoting love and cooperation. Morihei’s view came to be that the martial arts–traditionally tools of warring armies–must change their ways, and adopt a new model of loving compassion and protection of one’s enemies.

If the world is to escape further global destruction as occurred in the last world war, it must adopt a different way of thinking one that adopts cooperative methods, and not coercion and violence.

Morihei understood and modified many of Onisaburo’s concepts and goals in his own way. He applied them to aikido and defined its purpose as a bridge between Heaven and Earth and a way to achieve the loving protection of mankind. Aikido was an expression of the will of the kami or deities, God, if you will, and must be used to promote understanding among peoples.

Conclusion

Morihei’s spiritual master, Onisaburo Deguchi challenged political and religious authorities through the widespread activities of the Omoto sect. He publically criticized Japan’s leaders accusing them of the misuse of the imperial system to further its aims. The result of Onisaburo’s in-your-face opposition to the establishment was the nearly total suppression of the Omoto religion.

Morihei, for his part, chose a path of non-confrontation using budo by totally redefining its basic concept and assigning to it a life-affirming role, “katsujinken,” (life-giving sword) in contrast to the traditional view of martial arts as “satsujinken,” (killing sword). He turned the notion of budo–historically the tool of rulers and tyrants–on its head.

Whereas the Omoto religion is today only a shell of its former self, aikido–with its unique philosophy which also challenges the status quo but in a non-threatening way–has spread all the world over. Its ideas have entered into the mainstream of culture and provided an intriguing option to the “conquest and rule model” in which mankind has been stuck since recorded history.

This is the third of a three-part article. Read the first part here and the second part here.

Thank you for sharing.